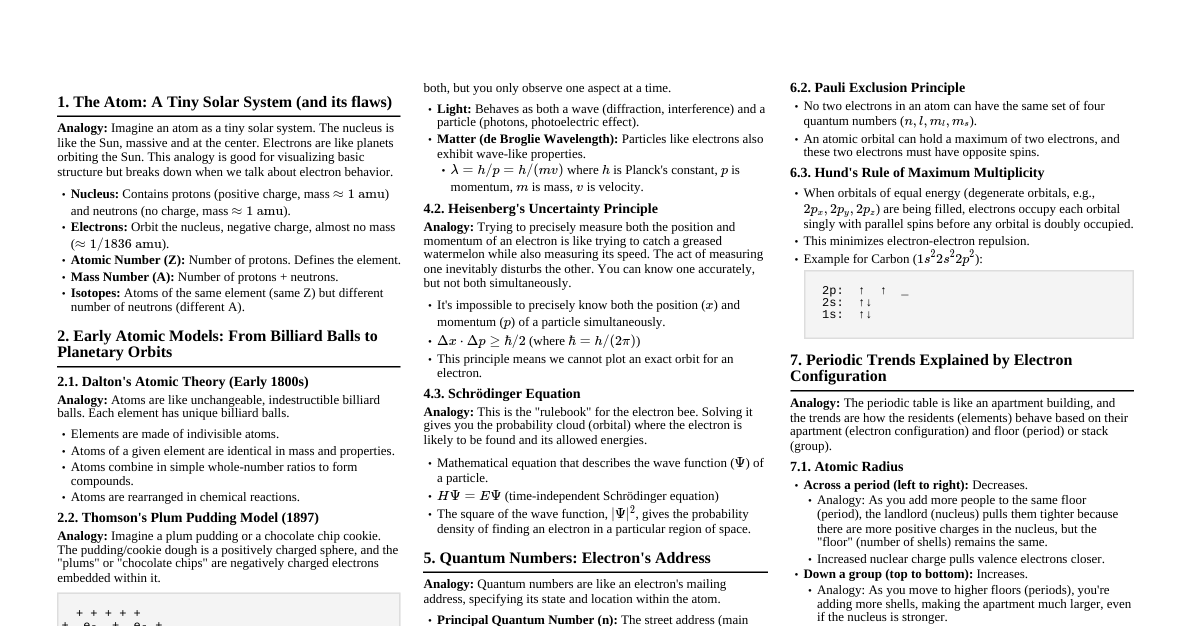

1. Fundamental Particles Electron (e-): Charge: $-1.602 \times 10^{-19} \text{ C}$ ($-1$ unit) Mass: $9.109 \times 10^{-31} \text{ kg}$ (approx. $1/1837$ of proton) Discovered by: J. J. Thomson (Cathode Ray Experiment) Charge-to-mass ratio ($e/m$): $-1.7588 \times 10^{11} \text{ C/kg}$ Proton (p+): Charge: $+1.602 \times 10^{-19} \text{ C}$ ($+1$ unit) Mass: $1.672 \times 10^{-27} \text{ kg}$ (approx. $1 \text{ amu}$) Discovered by: E. Goldstein (Anode Ray Experiment), named by Rutherford Neutron (n): Charge: $0$ Mass: $1.674 \times 10^{-27} \text{ kg}$ (approx. $1 \text{ amu}$, slightly heavier than proton) Discovered by: James Chadwick 2. Atomic Models Thomson's Model (Plum Pudding/Watermelon Model): Atom is a sphere of uniform positive charge with electrons embedded in it. Failed to explain Rutherford's $\alpha$-scattering experiment. Rutherford's Nuclear Model: Based on $\alpha$-scattering experiment (gold foil). Most of the atom is empty space. Positive charge and mass concentrated in a very small, dense nucleus at the center. Electrons revolve around the nucleus in circular paths. Drawbacks: Could not explain the stability of atoms (accelerating electrons should lose energy and spiral into nucleus, as per Maxwell's electromagnetic theory). Could not explain the line spectrum of elements. Bohr's Model of Hydrogen Atom: Postulates: Electrons revolve in certain fixed, stable orbits (stationary states) without radiating energy. Only those orbits are permitted in which the angular momentum of the electron is an integral multiple of $h/(2\pi)$. $L = m_e v r = n \frac{h}{2\pi}$, where $n=1, 2, 3, ...$ (principal quantum number). Energy is emitted/absorbed only when an electron jumps from one stationary state to another. $\Delta E = E_2 - E_1 = h\nu$. Formulas for H-like species ($Z$ is atomic number): Radius of $n^{th}$ orbit: $r_n = 0.529 \times \frac{n^2}{Z} \text{ Å}$ Energy of $n^{th}$ orbit: $E_n = -13.6 \times \frac{Z^2}{n^2} \text{ eV/atom}$ Velocity of electron in $n^{th}$ orbit: $v_n = 2.18 \times 10^6 \times \frac{Z}{n} \text{ m/s}$ Frequency of revolution: $f_n = \frac{v_n}{2\pi r_n} \propto \frac{Z^2}{n^3}$ NCERT Point: Bohr's model successfully explained stability and line spectra for H and H-like species. Limitations: Applicable only to single-electron species (H, He+, Li2+). Could not explain fine structure of spectral lines (Zeeman effect - splitting in magnetic field, Stark effect - splitting in electric field). Could not explain the ability of atoms to form molecules (chemical bonding). 3. Dual Nature of Matter (de Broglie) de Broglie's Hypothesis: Matter (like electrons) exhibits both particle and wave properties. de Broglie Wavelength: $\lambda = \frac{h}{p} = \frac{h}{mv}$, where $h$ is Planck's constant, $p$ is momentum, $m$ is mass, $v$ is velocity. For an electron accelerated through potential $V$ (in Volts): $\lambda = \frac{12.27}{\sqrt{V}} \text{ Å}$ NCERT Point: This hypothesis was experimentally confirmed by Davisson and Germer. Relation to Bohr's model: Bohr's condition for quantization of angular momentum ($mvr = n\frac{h}{2\pi}$) can be derived from de Broglie's concept of standing waves. For a stable orbit, the circumference must be an integral multiple of the de Broglie wavelength: $2\pi r = n\lambda = n\frac{h}{mv} \implies mvr = n\frac{h}{2\pi}$. JEE Mains PYQ Example (2020): Q: An electron is accelerated through a potential difference of $100$ V. What is the de Broglie wavelength associated with it? A: Given $V = 100 \text{ V}$. Using the formula: $\lambda = \frac{12.27}{\sqrt{V}} \text{ Å}$ $\lambda = \frac{12.27}{\sqrt{100}} = \frac{12.27}{10} = 1.227 \text{ Å}$ 4. Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle It is impossible to determine simultaneously, with absolute precision, both the position and momentum of a subatomic particle (like an electron). $\Delta x \cdot \Delta p \ge \frac{h}{4\pi}$ or $\Delta x \cdot m \Delta v \ge \frac{h}{4\pi}$ $\Delta E \cdot \Delta t \ge \frac{h}{4\pi}$ NCERT Point: This principle rules out the existence of definite paths or trajectories for electrons and other similar particles. It is significant for microscopic objects, but negligible for macroscopic objects. 5. Quantum Mechanical Model of Atom Based on wave mechanics (Schrödinger Equation). Describes electrons as waves. Schrödinger Wave Equation (Time-independent): $\hat{H}\psi = E\psi$ $\hat{H}$: Hamiltonian operator (total energy operator). $\psi$ (psi): Wave function, describes the amplitude of the electron wave. $E$: Total energy of the electron. Significance of $\psi^2$: Represents the probability density of finding an electron at a particular point in space. It is always positive. Atomic Orbitals: Regions of space around the nucleus where the probability of finding an electron is maximum (typically 90-95% probability contour). NCERT Point: The quantum mechanical model describes the probability of finding an electron around the nucleus, not its exact position. 6. Quantum Numbers These numbers arise naturally from the solution of Schrödinger equation and specify the exact location and energy of an electron in an atom. 1. Principal Quantum Number ($n$): $n = 1, 2, 3, ...$ (positive integers) Determines the main energy shell and size of the orbital. As $n$ increases, energy and average distance from nucleus increase. Number of orbitals in a shell = $n^2$. Maximum electrons in a shell = $2n^2$. Energy of electron in a multi-electron atom depends primarily on $n$ and $l$. 2. Azimuthal/Angular Momentum Quantum Number ($l$): $l = 0, 1, 2, ..., (n-1)$ Determines the subshell and shape of the orbital. $l=0 \implies s$ subshell (spherical) $l=1 \implies p$ subshell (dumbbell) $l=2 \implies d$ subshell (double dumbbell/complex) $l=3 \implies f$ subshell (complex) Number of orbitals in a subshell = $2l+1$. Maximum electrons in a subshell = $2(2l+1)$. Angular momentum of electron in an orbital = $\sqrt{l(l+1)} \frac{h}{2\pi}$. 3. Magnetic Quantum Number ($m_l$): $m_l = -l, ..., 0, ..., +l$ (including 0) Determines the orientation of the orbital in space. For $l=0 (s)$, $m_l=0$ (1 s orbital). For $l=1 (p)$, $m_l=-1, 0, +1$ (3 p orbitals: $p_x, p_y, p_z$). For $l=2 (d)$, $m_l=-2, -1, 0, +1, +2$ (5 d orbitals). 4. Spin Quantum Number ($m_s$): $m_s = +1/2$ (spin up) or $-1/2$ (spin down) Describes the intrinsic angular momentum (spin) of the electron. Represents two possible orientations of the electron's spin. Example: What are the possible quantum numbers for an electron in a $3p$ orbital? For a $3p$ orbital: Principal quantum number $n=3$. Azimuthal quantum number $l=1$ (since it's a $p$ orbital). Magnetic quantum number $m_l$ can be $-1, 0, +1$. Spin quantum number $m_s$ can be $+1/2$ or $-1/2$. So, a set of possible quantum numbers could be $(3, 1, -1, +1/2)$ or $(3, 1, 0, -1/2)$, etc. 7. Rules for Filling Orbitals Aufbau Principle: Electrons fill orbitals in order of increasing energy. Order: $1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, 5s, 4d, 5p, 6s, 4f, 5d, 6p, 7s, 5f, 6d, 7p, ...$ $(n+l)$ rule: Orbitals with lower $(n+l)$ value are filled first. If $(n+l)$ is same, then orbital with lower $n$ is filled first. Pauli's Exclusion Principle: No two electrons in an atom can have all four quantum numbers identical. An orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons, and these must have opposite spins. This means each electron in an atom has a unique set of four quantum numbers. Hund's Rule of Maximum Multiplicity: Pairing of electrons in degenerate orbitals ($p, d, f$) does not occur until each orbital in the subshell is singly occupied with parallel spins. Example: For $p^3$, fill as $\uparrow \uparrow \uparrow$ not $\uparrow\downarrow \uparrow$ This maximizes the total spin and thus stability. 8. Electronic Configuration Representation of the distribution of electrons in atomic orbitals. Example: Carbon (Z=6): $1s^2 2s^2 2p^2$ Oxygen (Z=8): $1s^2 2s^2 2p^4$ Chromium (Z=24): $[Ar] 3d^5 4s^1$ (Exceptional due to half-filled stability) Copper (Z=29): $[Ar] 3d^{10} 4s^1$ (Exceptional due to fully-filled stability) NCERT Point: Half-filled and fully-filled subshells have extra stability due to greater symmetry and more exchange energy. JEE Mains PYQ Example (2021): Q: The correct set of four quantum numbers for the valence electron of rubidium ($Z = 37$) is: A: Rubidium (Rb, $Z=37$). Electronic configuration: $1s^2 2s^2 2p^6 3s^2 3p^6 4s^2 3d^{10} 4p^6 5s^1$. The valence electron is in the $5s$ orbital. For $5s$ orbital, $n=5$. For $s$ orbital, $l=0$. For $l=0$, $m_l=0$. The electron can have $m_s = +1/2$ or $-1/2$. So, a correct set of quantum numbers is $(5, 0, 0, +1/2)$ or $(5, 0, 0, -1/2)$. 9. Shapes of Atomic Orbitals s-orbitals ($l=0$): Spherical in shape. As $n$ increases, size increases (e.g., $2s > 1s$). Probability density is maximum at the nucleus for $s$ orbitals (except for nodes). p-orbitals ($l=1$): Dumbbell shape. There are three $p$ orbitals: $p_x, p_y, p_z$, oriented along the x, y, and z axes respectively. These are degenerate in an isolated atom. The two lobes are separated by a nodal plane passing through the nucleus. d-orbitals ($l=2$): There are five $d$ orbitals: $d_{xy}, d_{yz}, d_{xz}, d_{x^2-y^2}, d_{z^2}$. Four of them ($d_{xy}, d_{yz}, d_{xz}, d_{x^2-y^2}$) have double dumbbell shapes. $d_{z^2}$ has a dumbbell shape along the z-axis with a 'doughnut' ring in the xy-plane. These are degenerate in an isolated atom. 10. Radial and Angular Nodes Nodes: Regions where the probability of finding an electron is zero ($\psi^2=0$). Total Number of Nodes: $n-1$ Number of Radial Nodes (Spherical Nodes): $n-l-1$ These are spherical shells where probability density is zero. Number of Angular Nodes (Nodal Planes): $l$ These are planar surfaces passing through the nucleus where probability density is zero. For $s$ orbitals ($l=0$), 0 angular nodes. For $p$ orbitals ($l=1$), 1 angular node. For $d$ orbitals ($l=2$), 2 angular nodes. Example: Calculate the number of radial and angular nodes for a $4f$ orbital. For a $4f$ orbital, $n=4$ and $l=3$. Number of radial nodes = $n-l-1 = 4-3-1 = 0$. Number of angular nodes = $l = 3$. Total number of nodes = $n-1 = 4-1 = 3$. (Check: $0+3=3$) 11. Photoelectric Effect Emission of electrons when light of suitable frequency strikes a metal surface. Key observations: Electrons are ejected only if incident light has frequency ($\nu$) greater than threshold frequency ($\nu_0$). Kinetic energy of ejected electrons increases linearly with frequency of incident light. Number of ejected electrons is proportional to intensity of incident light. No time lag between incidence of light and ejection of electrons. Einstein's Equation: $h\nu = h\nu_0 + KE_{max}$ $h\nu$: Energy of incident photon. $h\nu_0$ (Work Function, $W_0$): Minimum energy required to eject an electron. $KE_{max}$: Maximum kinetic energy of ejected electron. $KE_{max} = \frac{1}{2}m_e v^2$. NCERT Point: This effect provided strong evidence for the particle nature of light (photons). JEE Mains PYQ Example (2022): Q: A photon of energy $3.55 \text{ eV}$ is incident on a metal surface having work function $1.5 \text{ eV}$. The kinetic energy of the fastest emitted photoelectron is: A: Given, Energy of incident photon $h\nu = 3.55 \text{ eV}$. Work function $h\nu_0 = 1.5 \text{ eV}$. Using Einstein's photoelectric equation: $KE_{max} = h\nu - h\nu_0$ $KE_{max} = 3.55 \text{ eV} - 1.5 \text{ eV} = 2.05 \text{ eV}$. 12. Atomic Spectra (Hydrogen Spectrum) When atomic hydrogen gas is excited, it emits light of specific wavelengths. Rydberg Formula: $\frac{1}{\lambda} = R_H Z^2 \left( \frac{1}{n_1^2} - \frac{1}{n_2^2} \right)$ $R_H$: Rydberg constant ($1.09677 \times 10^7 \text{ m}^{-1}$ or $109677 \text{ cm}^{-1}$) $Z$: Atomic number (1 for H) $n_1$: Lower energy level (final state) $n_2$: Higher energy level (initial state), $n_2 > n_1$ Energy of transition: $\Delta E = h\nu = \frac{hc}{\lambda} = R_H hc Z^2 \left( \frac{1}{n_1^2} - \frac{1}{n_2^2} \right)$ Spectral Series: Lyman Series: $n_1=1$, $n_2=2,3,4,...$ (Ultraviolet region) Balmer Series: $n_1=2$, $n_2=3,4,5,...$ (Visible region) Paschen Series: $n_1=3$, $n_2=4,5,6,...$ (Infrared region) Brackett Series: $n_1=4$, $n_2=5,6,7,...$ (Infrared region) Pfund Series: $n_1=5$, $n_2=6,7,8,...$ (Infrared region) Humphrey Series: $n_1=6$, $n_2=7,8,9,...$ (Far Infrared region) Ionization Energy (IE): Energy required to remove an electron from an isolated gaseous atom in its ground state. For H atom, IE from ground state ($n=1$ to $n=\infty$) = $13.6 \text{ eV}$. For H-like species, $IE = 13.6 \times Z^2 \text{ eV}$. NCERT Point: The line spectrum of hydrogen provided crucial evidence for the quantized energy levels in atoms. JEE Mains PYQ Example (2023): Q: The wavelength of the first spectral line in the Balmer series of the hydrogen spectrum is $\lambda$. What is the wavelength of the first spectral line in the Balmer series of Li$^{2+}$ ion? A: For Balmer series, $n_1=2$. The first spectral line implies $n_2 = n_1+1 = 3$. Rydberg formula: $\frac{1}{\lambda} = R_H Z^2 \left( \frac{1}{n_1^2} - \frac{1}{n_2^2} \right)$ For Hydrogen ($Z=1$): $\frac{1}{\lambda_H} = R_H (1)^2 \left( \frac{1}{2^2} - \frac{1}{3^2} \right) = R_H \left( \frac{1}{4} - \frac{1}{9} \right) = R_H \left( \frac{9-4}{36} \right) = R_H \frac{5}{36}$ Given $\lambda_H = \lambda$, so $\frac{1}{\lambda} = R_H \frac{5}{36}$. For Li$^{2+}$ ($Z=3$): $\frac{1}{\lambda_{Li}} = R_H (3)^2 \left( \frac{1}{2^2} - \frac{1}{3^2} \right) = 9 R_H \left( \frac{5}{36} \right) = \frac{5}{4} R_H$ Substitute $R_H \frac{5}{36} = \frac{1}{\lambda}$ into the equation for Li$^{2+}$: $\frac{1}{\lambda_{Li}} = 9 \left( \frac{1}{\lambda} \right) = \frac{9}{\lambda}$ Therefore, $\lambda_{Li} = \frac{\lambda}{9}$. 13. Important NCERT Points to Ponder Electromagnetic Radiation: Dual nature (wave and particle). Wave properties: wavelength ($\lambda$), frequency ($\nu$), speed ($c$), amplitude. Particle properties: Photons with energy $E=h\nu = hc/\lambda$. Black Body Radiation: Explained by Planck's quantum theory, which states energy is emitted/absorbed in discrete packets called quanta ($E=h\nu$). Classical physics failed to explain it. Wave Number: $\bar{\nu} = \frac{1}{\lambda} = \frac{\nu}{c}$. Unit is $\text{m}^{-1}$ or $\text{cm}^{-1}$. Ground State: The lowest energy state of an electron in an atom ($n=1$ for H). Excited State: Any energy state higher than the ground state ($n>1$ for H). Degenerate Orbitals: Orbitals having the same energy (e.g., $2p_x, 2p_y, 2p_z$ in an isolated atom). In presence of external fields or in multi-electron atoms, degeneracy might be lifted. Shielding Effect / Screening Effect: Inner shell electrons reduce the nuclear attraction felt by outer shell electrons. This affects the energy of orbitals in multi-electron atoms (e.g., $E_{1s} Penetration Effect: The ability of an electron to approach the nucleus. $s$-orbitals have greater penetration power than $p$, $d$, or $f$ orbitals for the same $n$. This also influences orbital energies. Isotopes: Atoms of the same element with same atomic number ($Z$) but different mass numbers ($A$) due to different number of neutrons. Isobars: Atoms with same mass number ($A$) but different atomic numbers ($Z$). Isotones: Atoms with same number of neutrons but different atomic and mass numbers. Isoelectronic species: Atoms/ions having the same number of electrons (e.g., $\text{Na}^+, \text{Mg}^{2+}, \text{Al}^{3+}, \text{Ne}$).