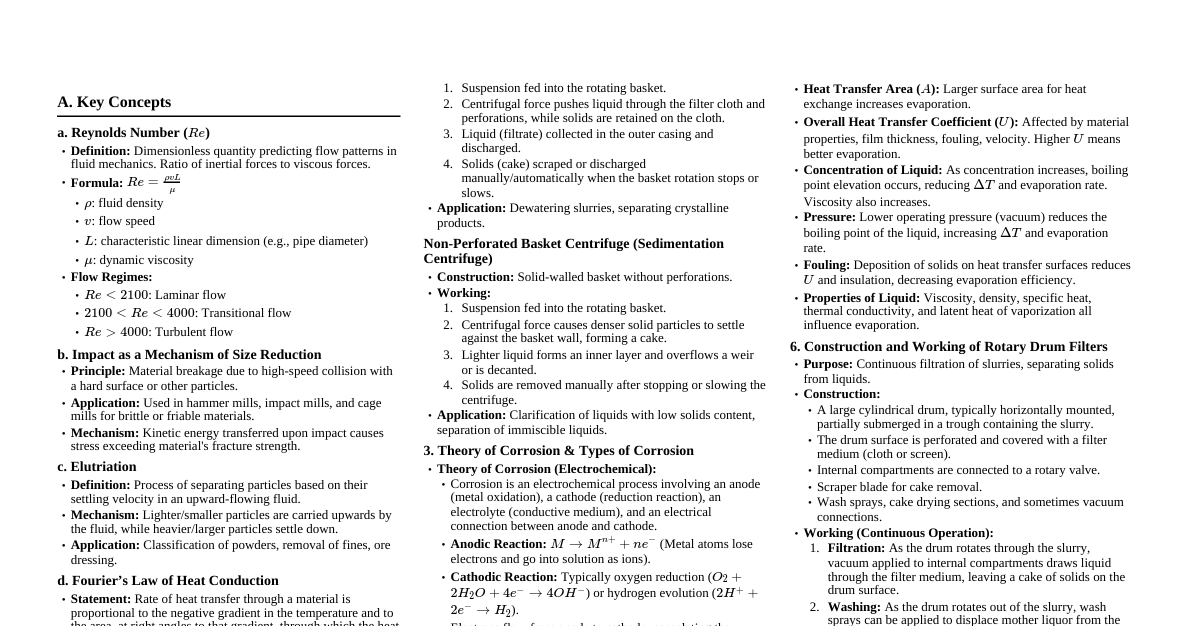

Crystallography Definition: The study of the geometrical form and physical properties of crystalline solids. Crystalline Solids: Regular, periodic arrangement of atoms/molecules (e.g., quartz, metals). Can be single or polycrystalline. Amorphous Solids: Random arrangement of atoms/molecules, short-range order (e.g., silica glass). Crystalline vs. Amorphous Solids Property Crystalline Amorphous Arrangement Regular, periodic Random Repeating Units Yes No Order Long-range Short-range Anisotropy Anisotropic Isotropic Melting Point Sharp Over a range Space Lattice, Basis, and Crystal Structure Space Lattice: Infinite array of points in 3D, each with identical surroundings. Lattice Points: Denote positions of atoms/molecules. Basis: An atom or group of atoms placed at each lattice point. Crystal Structure: Space Lattice + Basis. Unit Cell and Lattice Parameters Unit Cell: Smallest block that, by repetition, builds the entire crystal. Primitive Cell: Lattice points only at corners. Non-Primitive Cell: Lattice points at corners and other locations (body-centered, face-centered, base-centered). Lattice Parameters: $a, b, c$ (edge lengths) and $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$ (interfacial angles). Crystal Systems (7 Basic Types) System Parameters Angles Bravais Lattices Cubic $a=b=c$ $\alpha=\beta=\gamma=90^\circ$ P, I, F Tetragonal $a=b \ne c$ $\alpha=\beta=\gamma=90^\circ$ P, I Orthorhombic $a \ne b \ne c$ $\alpha=\beta=\gamma=90^\circ$ P, I, F, C Monoclinic $a \ne b \ne c$ $\alpha=\gamma=90^\circ, \beta \ne 90^\circ$ P, C Triclinic $a \ne b \ne c$ $\alpha \ne \beta \ne \gamma \ne 90^\circ$ P Rhombohedral $a=b=c$ $\alpha=\beta=\gamma \ne 90^\circ$ P Hexagonal $a=b \ne c$ $\alpha=\beta=90^\circ, \gamma=120^\circ$ P Bravais Lattices: There are 14 unique ways to arrange points in 3D space, belonging to the 7 crystal systems. Miller Indices $(hkl)$ Notation for planes in Bravais lattices. Reciprocals of the fractional intercepts the plane makes with crystallographic axes, converted to smallest integers. $(hkl)$ defines a single plane. $\{hkl\}$ defines a family of planes. $[hkl]$ defines a direction. $ $ defines a family of directions. If a plane is parallel to an axis, its intercept is $\infty$, and its Miller index is $0$. Interplanar Spacing in Cubic System For a cubic system ($a=b=c$): $d_{hkl} = \frac{a}{\sqrt{h^2 + k^2 + l^2}}$ Expression for Lattice Constant of a Cubic Crystal Density $\rho = \frac{n \cdot M}{a^3 \cdot N_a}$ Lattice constant $a = \left( \frac{n \cdot M}{\rho \cdot N_a} \right)^{1/3}$ Where $n$: number of molecules per unit cell, $M$: molecular weight, $N_a$: Avogadro number. X-Ray Diffraction Diffraction: Bending of waves around obstacles. Occurs when obstacle size $\approx$ wavelength. X-rays have wavelengths ($\sim 1 \text{ Å}$) comparable to atomic spacing in crystals. Crystals act as 3D gratings for X-rays. Bragg's Law Condition for constructive interference of X-rays reflected from crystal planes: $n\lambda = 2d \sin\theta$ $n$: integer order of diffraction, $\lambda$: X-ray wavelength, $d$: interplanar spacing, $\theta$: glancing angle. Powder Diffraction Method Uses a fine powder sample (randomly oriented tiny crystals) and monochromatic X-rays. Diffraction from all possible planes forms cones of diffracted beams. These cones produce characteristic arcs on a photographic film. Used to determine lattice constants and crystal structure. Advantages: No need for large single crystals, easy to perform, small crystals suffice. Crystal Defects Any deviation from the perfect periodic arrangement of atoms. Affects properties like mechanical strength, ductility, conductivity. Classification of Crystal Defects Point Defects (0D): Vacancies, impurity defects. Line Defects (1D): Dislocations (edge, screw). Surface Defects (2D): Grain boundaries, twin boundaries. Volume Defects (3D): Cavities, cracks. Point Defects Limited to a lattice position or interstice. Increase internal energy and electrical resistance. Impurity Defects: Substitutional: Foreign atom occupies host atom's site. Interstitial: Small foreign atom fits into interstitial spaces. Vacancies: Unoccupied atomic sites. Frenkel Defect: An ion displaced from its lattice site to an interstitial site, creating a vacancy and an interstitial defect. Density of crystal unchanged. Electrical neutrality maintained. Concentration $n = (N N_i)^{1/2} \exp\left( -\frac{E_i}{2KT} \right)$ $N$: lattice positions, $N_i$: interstitial positions, $E_i$: energy to form defect, $K$: Boltzmann constant, $T$: temperature. Schottky Defect: A missing atom from its lattice site. Decreases crystal density. In ionic crystals, it's a pair of cation and anion vacancies to maintain neutrality. In Metals: Concentration $n \approx N \exp\left( -\frac{E_v}{KT} \right)$ In Ionic Crystals: Concentration $n \approx N \exp\left( -\frac{E_p}{2KT} \right)$ $N$: total lattice positions, $E_v/E_p$: energy to form defect. Line Defects (Dislocations) Disturbed region between two perfect crystal parts. Arise from growth accidents, thermal/external stresses. Edge Dislocation: Extra half-plane of atoms inserted. Positive ('$\perp$') if extra plane is above slip plane, negative ('$\top$') if below. Screw Dislocation: Displacement of atoms forming a spiral ramp around the dislocation line. Burger's Vector ($b$): Quantifies the direction and magnitude of lattice distortion. For edge dislocation, $b$ is perpendicular to dislocation line. For screw dislocation, $b$ is parallel to dislocation line. Wave Mechanics De Broglie Hypothesis (Matter Waves) Dual Nature of Matter: Like light, matter (particles) also exhibits both wave and particle nature. Matter Waves: Waves associated with material particles in motion. De Broglie Wavelength: $\lambda = \frac{h}{p} = \frac{h}{mv}$ $h$: Planck's constant, $p$: momentum, $m$: mass, $v$: velocity. De Broglie Wavelength in Different Forms In terms of Kinetic Energy ($E$): $\lambda = \frac{h}{\sqrt{2mE}}$ In terms of Voltage ($V$) for charged particle $q$: $\lambda = \frac{h}{\sqrt{2mqV}}$ For electron: $\lambda = \frac{12.24}{\sqrt{V}} \text{ Å}$ In terms of Temperature ($T$): $\lambda = \frac{h}{\sqrt{3mk_BT}}$ $k_B$: Boltzmann constant. Properties of Matter Waves Lighter particles have greater wavelength. Lower velocity means longer wavelength. $\lambda \to \infty$ when $v=0$; $\lambda \to 0$ when $v \to \infty$. Can be produced by charged or uncharged particles. Are not electromagnetic waves. Travel faster than the velocity of light. Wave nature implies uncertainty in particle position. Wave Function ($\Psi$) Variable quantity associated with a moving particle at $(x,y,z,t)$. $\Psi = \Psi_0 e^{-i\omega t}$ or $\Psi(x,y,z,t) = \Psi_0 e^{-i(\omega t - kx)}$. Complex quantity, no direct physical meaning. $|\Psi|^2 = \Psi\Psi^*$ is real and positive, representing probability density (probability of finding particle per unit volume). Probability $P = \iiint |\Psi|^2 d\Gamma$. ($0 \le P \le 1$) Properties: Single-valued, finite, continuous, analytical (continuous first derivative), vanishes at boundaries. Normalized Wave Function: If $\iiint |\Psi|^2 d\Gamma = 1$. Schrödinger Wave Equations Fundamental equations of quantum physics describing particle behavior. Based on classical wave equation, de Broglie hypothesis, and conservation of energy. Momentum Operator: $\hat{p} = -i\hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial x}$ Energy Operator: $\hat{E} = i\hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t}$ $\hbar = h/2\pi$. Schrödinger Time-Dependent Wave Equation In 1D: $-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \frac{\partial^2\Psi}{\partial x^2} + V\Psi = i\hbar \frac{\partial\Psi}{\partial t}$ In 3D: $-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2\Psi + V\Psi = i\hbar \frac{\partial\Psi}{\partial t}$ $\nabla^2 = \frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2}{\partial y^2} + \frac{\partial^2}{\partial z^2}$ (Laplacian operator) Can be written as $\hat{H}\Psi = i\hbar \frac{\partial\Psi}{\partial t}$, where $\hat{H}$ is the Hamiltonian operator. Schrödinger Time-Independent Wave Equation Assumes $\Psi(x,t) = \psi(x)\phi(t)$. For stationary states, $E\psi = -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2\psi + V\psi$. In 1D: $-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \frac{d^2\psi}{dx^2} + V\psi = E\psi$ or $\frac{d^2\psi}{dx^2} + \frac{2m}{\hbar^2}(E-V)\psi = 0$ In 3D: $\nabla^2\psi + \frac{2m}{\hbar^2}(E-V)\psi = 0$ Can be written as $\hat{H}\psi = E\psi$. Particle in a 1D Box (Infinite Square Well) Potential Energy: $V(x) = 0$ for $0 Schrödinger Equation (inside box): $\frac{d^2\psi}{dx^2} + \frac{2mE}{\hbar^2}\psi = 0$ Wave Function: $\psi_n(x) = \sqrt{\frac{2}{L}} \sin\left(\frac{n\pi x}{L}\right)$ Allowed Energies: $E_n = \frac{n^2\pi^2\hbar^2}{2mL^2} = \frac{n^2h^2}{8mL^2}$, where $n = 1, 2, 3, \dots$ Key Results: Energy is quantized. Lowest possible energy ($n=1$) is not zero (zero-point energy). Probability density $|\psi_n(x)|^2$ shows nodes (zero probability) increasing with $n$. Electromagnetic Theory Maxwell's Equations (Differential Forms) Gauss's Law for Electricity: $\nabla \cdot \mathbf{D} = \rho$ (or $\nabla \cdot \mathbf{E} = \rho/\epsilon_0$) Relates electric field to charge density. Gauss's Law for Magnetism: $\nabla \cdot \mathbf{B} = 0$ Magnetic monopoles do not exist. Faraday's Law of Induction: $\nabla \times \mathbf{E} = -\frac{\partial \mathbf{B}}{\partial t}$ Changing magnetic field induces electric field. Ampere-Maxwell Law: $\nabla \times \mathbf{H} = \mathbf{J} + \frac{\partial \mathbf{D}}{\partial t}$ (or $\nabla \times \mathbf{B} = \mu_0\mathbf{J} + \mu_0\epsilon_0\frac{\partial \mathbf{E}}{\partial t}$) Electric current and changing electric field (displacement current) produce magnetic field. Conducting Current and Displacement Current Conducting Current Density ($\mathbf{J}_c$): Due to flow of free charges (e.g., electrons in a wire). $\mathbf{J}_c = \sigma \mathbf{E}$. Displacement Current Density ($\mathbf{J}_d$): Due to changing electric field (e.g., in a capacitor). $\mathbf{J}_d = \frac{\partial \mathbf{D}}{\partial t}$. Total Current Density: $\mathbf{J} = \mathbf{J}_c + \mathbf{J}_d$. Electric Vectors and Their Relations Electric Field Intensity ($\mathbf{E}$): Force per unit charge. Electric Displacement Field ($\mathbf{D}$): $\mathbf{D} = \epsilon_0 \mathbf{E} + \mathbf{P}$. Dielectric Polarization ($\mathbf{P}$): Dipole moment per unit volume. Relative Permittivity ($\epsilon_r$) or Dielectric Constant ($\kappa$): $\mathbf{D} = \epsilon_r \epsilon_0 \mathbf{E}$. Electric Susceptibility ($\chi_e$): $\mathbf{P} = \epsilon_0 \chi_e \mathbf{E}$. Relation: $\epsilon_r = 1 + \chi_e$. Electromagnetic Wave Equations (in Free Space) From Maxwell's equations, for free space ($\rho=0, \mathbf{J}=0$): $\nabla^2 \mathbf{E} = \mu_0 \epsilon_0 \frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{E}}{\partial t^2}$ $\nabla^2 \mathbf{B} = \mu_0 \epsilon_0 \frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{B}}{\partial t^2}$ These are wave equations. The speed of EM waves in free space is $c = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu_0 \epsilon_0}} \approx 3 \times 10^8 \text{ m/s}$. Poynting Theorem and Vector Poynting Theorem: Describes energy conservation in EM fields. $\oint_S (\mathbf{E} \times \mathbf{H}) \cdot d\mathbf{S} = -\frac{\partial}{\partial t} \int_V \left(\frac{1}{2}\epsilon_0 E^2 + \frac{1}{2\mu_0} B^2\right) dV - \int_V \mathbf{J} \cdot \mathbf{E} dV$ Total power leaving volume = Rate of decrease of stored EM energy - Ohmic power dissipated. Poynting Vector ($\mathbf{P}$): $\mathbf{P} = \mathbf{E} \times \mathbf{H}$ (or $\mathbf{P} = \frac{1}{\mu_0} (\mathbf{E} \times \mathbf{B})$). Represents the rate of energy flow per unit area (power density) in EM waves. Units: $\text{W/m}^2$. Direction is perpendicular to both $\mathbf{E}$ and $\mathbf{H}$. Magnetic Materials Basic Definitions Intensity of Magnetization ($\mathbf{M}$ or $\mathbf{I}$): Magnetic moment per unit volume. $\mathbf{M} = \mu_m / V$. Magnetic Susceptibility ($\chi$): Ratio of magnetization to magnetic field intensity. $\chi = M/H$. Dimensionless. Relation between $B, H, M$: $\mathbf{B} = \mu_0 (\mathbf{H} + \mathbf{M})$. Classification of Magnetic Materials Based on their response to external magnetic fields. Diamagnetic: Paired electrons, no permanent dipoles. Weakly repelled by magnetic fields. Move from stronger to weaker field. $\chi$ is negative, small, and independent of temperature. Relative permeability $\mu_r Examples: Bi, Zn, Gold, Silver, H$_2$. Paramagnetic: Unpaired electrons, small net magnetic moment per atom. Weakly attracted by magnetic fields. Move from weaker to stronger field. $\chi$ is positive, small. Follows Curie's Law: $\chi = C/T$. $\mu_r > 1$. Examples: Al, Pt, Mn. Ferromagnetic: Strong spontaneous magnetization due to parallel alignment of dipoles (exchange interaction). Strongly attracted by magnetic fields. $\chi$ is positive and very large. Follows Curie-Weiss Law: $\chi = \frac{C}{T-\theta}$ (for $T > \theta$, Curie temperature). Exhibits magnetic domains and hysteresis. Examples: Fe, Ni, Co. Antiferromagnetic: Anti-parallel magnetic moments of equal magnitude, resulting in zero net magnetization. $\chi$ is small, positive, and temperature-dependent. Max at Neel temperature ($T_N$). Examples: MnO, FeO, Cr. Ferrimagnetic: Anti-parallel magnetic moments of unequal magnitude, resulting in a net spontaneous magnetization. $\chi$ is positive and large. Examples: Ferrites (e.g., ZnFe$_2$O$_4$). Weiss Molecular Field Theory of Ferromagnetism Ferromagnetic materials have internal molecular fields that align magnetic moments into domains. Each domain is spontaneously magnetized. Internal molecular field $H_i = \lambda M$. Curie-Weiss Law: $\chi = \frac{C}{T-\theta}$ where $\theta$ is the Curie temperature. Explains temperature dependence of susceptibility above $\theta$. Hysteresis Curve (B-H Curve) Lag of magnetization ($\mathbf{B}$) behind the applied magnetic field ($\mathbf{H}$). Retentivity (Remanence): Magnetic field retained when $H=0$. Coercivity: Magnetic field required to reduce magnetization to zero. Area of the loop represents energy loss per cycle. Hard and Soft Magnetic Materials Soft Magnetic Materials: Easily magnetized and demagnetized. Small hysteresis loop area (low energy loss). High permeability and susceptibility. Low coercivity and retentivity. Applications: Transformer cores, electromagnets. Examples: Iron-silicon alloys. Hard Magnetic Materials: Difficult to magnetize and demagnetize. Large hysteresis loop area (high energy loss). Low permeability and susceptibility. High coercivity and retentivity. Applications: Permanent magnets, magnetic detectors. Examples: Cobalt steel, Alnico alloys. Superconductivity Discovery: H.K. Onnes (1911) observed zero resistivity in mercury at low temperatures. Definition: Phenomenon of almost zero resistivity (infinite conductivity) in certain metals/alloys when cooled below a critical temperature. General Properties of Superconductors Critical Temperature ($T_c$): Temperature below which a material becomes superconducting. Varies for different materials. Zero Electrical Resistance: Perfect conductivity below $T_c$. Persistent currents can flow indefinitely. Meissner Effect: Expulsion of magnetic flux from the interior of a superconductor when cooled below $T_c$ in a magnetic field. Superconductors are perfect diamagnets ($\chi = -1$). Magnetic levitation. Critical Magnetic Field ($H_c$): Magnetic field strength above which superconductivity is destroyed. $H_c(T) = H_c(0)[1 - (T/T_c)^2]$. Critical Current Density ($J_c$): Current density above which superconductivity is destroyed. Isotope Effect: $T_c \propto 1/\sqrt{M}$ ($M$: isotopic mass). Types of Superconductors Type-I (Soft) Superconductors: Abruptly lose superconductivity above $H_c$. Exhibit complete Meissner effect. Examples: Al, Zn, Pb, Hg. Limited to low magnetic fields. Type-II (Hard) Superconductors: Gradually lose superconductivity between lower critical field ($H_{c1}$) and upper critical field ($H_{c2}$). Allow magnetic flux penetration in vortex state between $H_{c1}$ and $H_{c2}$. Exhibit incomplete Meissner effect. Examples: NbTi, Nb$_3$Sn, High-$T_c$ superconductors. Used for strong field superconducting magnets. BCS Theory (Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer) Explains superconductivity at low temperatures. Based on formation of Cooper Pairs: Two electrons interact via lattice vibrations (phonons), forming a bound pair. Cooper pairs have opposite momenta and spin, do not transfer energy to the lattice, leading to zero resistance. High-Temperature Superconductors (HTSC) Materials with $T_c$ above the boiling point of liquid nitrogen (77 K). Mostly ceramic copper oxides (cuprates). Examples: YBa$_2$Cu$_3$O$_7$ ($T_c \approx 92 \text{ K}$), Bi-Sr-Ca-Cu-O systems ($T_c \approx 110 \text{ K}$). Applications of Superconductors MAGLEV Trains: Magnetic levitation for high-speed transport. Medical Imaging: NMR tomography. Power Transmission: Fault-free power cables, high-power motors. Electronics: Faster computing (SQUIDs), sensitive detectors. LASERS Introduction to LASERs LASER: Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. Produces highly directional, coherent, monochromatic, polarized light. Invented by C.H. Townes and A. Schawlow (theory), T.H. Maiman (first device, Ruby laser in 1960). Characteristics of Laser Light Monochromatic: Very narrow range of wavelengths (single color). Directional: Emitted as a narrow, low-divergence beam. Coherent: Waves are in phase spatially and temporally. High Intensity: Energy concentrated in a small area. Basic Concepts for Laser Operation Absorption: Atom absorbs energy, electron excites to a higher energy level. Spontaneous Emission: Excited atom emits a photon randomly and decays to a lower state. Incoherent. Stimulated Emission: Incoming photon of specific energy triggers an excited atom to emit an identical photon. Coherent. Population Inversion: More atoms in a higher excited state than in a lower state. Necessary condition for lasing. Pumping: Process of achieving population inversion (e.g., optical, electrical). Einstein's Coefficients $B_{12}$: Probability of stimulated absorption. $A_{21}$: Probability of spontaneous emission. $B_{21}$: Probability of stimulated emission. Relations: $B_{12} = B_{21}$ (for non-degenerate levels) $\frac{A_{21}}{B_{21}} = \frac{8\pi h \nu^3}{c^3}$ Types of Lasers Ruby Laser (Solid-State): Active Medium: Chromium ions (Cr$^{3+}$) in Al$_2$O$_3$ crystal. Pumping: Optical pumping (flash lamp). Output: Pulsed red light ($\lambda = 694.3 \text{ nm}$). Three-level system. He-Ne Laser (Gas Laser): Active Medium: Mixture of Helium and Neon gas (10:1 ratio). Pumping: Electrical discharge. Output: Continuous red light ($\lambda = 632.8 \text{ nm}$). Four-level system. Energy transfer from excited He to Ne. Semiconductor Laser (Diode Laser): Active Medium: p-n junction diode (e.g., GaAs). Pumping: Forward bias injection. Output: Coherent light, wavelength depends on bandgap. Compact, efficient, widely used in optical communication, barcode scanners. Applications of Lasers Medicine: Surgery (precision cutting), ophthalmology (retina reattachment, vision correction), cancer treatment. Industry: Cutting, drilling, welding, surface treatment, alignment. Communication: Optical fiber communication, free-space optical communication. Information Technology: Barcode scanners, CD/DVD/Blu-ray players, laser printers. Scientific Research: Spectroscopy, interferometry. Military: Ranging, targeting, missile defense. Fibre Optics Introduction to Optical Fibers Hair-thin cylindrical structure of glass or plastic that guides light. Based on the principle of Total Internal Reflection (TIR). Used for high-bandwidth communication. Optical Fiber Structure Core: Inner-most cylinder, higher refractive index ($n_1$). Light propagates here. Cladding: Surrounds the core, lower refractive index ($n_2$), where $n_1 > n_2$. Ensures TIR. Outer Jacket (Buffer): Protects the fiber from moisture and provides mechanical strength. Principle of Total Internal Reflection (TIR) Occurs when light travels from a denser medium ($n_1$) to a rarer medium ($n_2$) where $n_1 > n_2$. If the angle of incidence ($\theta_i$) in the denser medium exceeds the critical angle ($\theta_c$), light is reflected back into the denser medium. Critical Angle: $\theta_c = \sin^{-1}\left(\frac{n_2}{n_1}\right)$. Propagation of Light through Optical Fiber Light launched into the core undergoes successive TIRs at the core-cladding interface. Acceptance Angle ($\theta_a$): Maximum angle of incidence at the fiber face for light to be guided by TIR. $\sin\theta_a = \sqrt{n_1^2 - n_2^2}$ (assuming air outside fiber, $n_0=1$). Numerical Aperture (NA): Measure of the light-gathering capability of a fiber. $\text{NA} = \sin\theta_a = \sqrt{n_1^2 - n_2^2}$. Acceptance Cone: Cone formed by rotating the acceptance angle around the fiber axis. Light within this cone is accepted. Fractional Refractive Index Change ($\Delta$): $\Delta = \frac{n_1 - n_2}{n_1}$. Relation between NA and $\Delta$: $\text{NA} \approx n_1 \sqrt{2\Delta}$. Types of Optical Fibers Based on Material: Glass core with Glass cladding. Plastic core with Plastic cladding. Glass core with Plastic cladding. Based on Modes of Propagation: Single-Mode Fiber (SMF): Only one path for light. Small core diameter ($\sim 7-10 \text{ µm}$). Low dispersion, used for long-distance communication. Multi-Mode Fiber (MMF): Multiple paths for light. Larger core diameter ($\sim 50-100 \text{ µm}$). Higher dispersion (signal degradation), used for short-distance communication. Based on Refractive Index Profile: Step-Index Fiber: Uniform refractive index in core ($n_1$) and cladding ($n_2$). Abrupt change at interface. Light travels in zig-zag paths (meridional rays). Graded-Index Fiber (GRIN): Core refractive index gradually decreases from center to cladding interface. Light rays follow helical paths (skew rays), focusing effect reduces dispersion. Fiber Configurations Single-Mode Step-Index (SMSI): Small core, step index profile, single mode. Multi-Mode Step-Index (MMSI): Large core, step index profile, multiple modes. Multi-Mode Graded-Index (MMGI): Large core, graded index profile, multiple modes. Fiber Drawing Process (Double Crucible Method) Core and cladding materials (molten glass) are placed in concentric crucibles. Drawn simultaneously through nozzles to form a continuous fiber. Losses in Optical Fibers (Attenuation) Reduction in signal strength over distance. Measured in dB/km. $\alpha = \frac{10}{L} \log_{10}\left(\frac{P_{in}}{P_{out}}\right)$ dB/km. Absorption Losses: Impurity Absorption: By transition metal ions (Fe, Cr, Cu) or OH-ions. Intrinsic Absorption: By fiber material itself. Scattering Losses: Rayleigh Scattering: Due to variations in material density or refractive index. Proportional to $1/\lambda^4$. Radiative Losses (Bending Losses): Macroscopic Bending: Large bends cause light to escape. Microscopic Bending: Small, random bends due to cabling/manufacturing defects. Applications of Optical Fibers Communication: High-bandwidth data transmission (telephone, internet, video), LANs, underwater networks. Medical Field: Endoscopes, laser surgery, diagnostic tools. Sensing Applications: Fiber optic sensors for displacement, pressure, temperature, etc. Illumination: Decorative lighting. Band Theory of Solids Energy Bands in Solids In isolated atoms, electrons have discrete energy levels. In solids, atomic orbitals overlap, leading to splitting of energy levels and formation of continuous energy bands . Valence Band: Formed by valence electrons. Highest occupied band at 0 K. Conduction Band: Formed by free electrons. Lowest unoccupied band at 0 K. Forbidden Gap ($E_g$): Energy region between valence and conduction bands where no electron states exist. Classification of Materials based on Forbidden Gap Insulators: Large $E_g$ ($\approx 15 \text{ eV}$). Valence band full, conduction band empty. No free electrons for conduction. Examples: Wood, plastic, diamond. Conductors: $E_g \approx 0$ (valence and conduction bands overlap). Many free electrons available for conduction. Examples: Cu, Al, Fe. Semiconductors: Small $E_g$ ($\approx 0.1 \text{ eV}$ to $3 \text{ eV}$). At 0 K, behave as insulators. At room temperature, some electrons jump to conduction band. Conductivity increases with temperature (negative temperature coefficient of resistance). Examples: Si ($E_g \approx 1.12 \text{ eV}$), Ge ($E_g \approx 0.67 \text{ eV}$). Concept of Hole A vacancy created in the valence band when an electron jumps to the conduction band. Behaves as a positive charge carrier with charge equal to electron but opposite polarity. Types of Semiconductors Intrinsic Semiconductors: Pure semiconductors (e.g., Si, Ge). Number of electrons in conduction band ($n_e$) equals number of holes in valence band ($n_h$). Fermi level lies in the middle of the forbidden gap. Extrinsic Semiconductors: Doped with impurities. Overall neutral charge. N-type: Doped with pentavalent impurities (donors, e.g., P, As). Majority carriers: electrons. Minority carriers: holes. Fermi level shifts closer to the conduction band. P-type: Doped with trivalent impurities (acceptors, e.g., B, Ga). Majority carriers: holes. Minority carriers: electrons. Fermi level shifts closer to the valence band. Carrier Concentration in Intrinsic Semiconductors Electron Density ($n_e$): Number of electrons in conduction band per unit volume. $n_e = N_c \exp\left(-\frac{E_c - E_F}{KT}\right)$ $N_c$: effective density of states in conduction band. Hole Density ($n_h$): Number of holes in valence band per unit volume. $n_h = N_v \exp\left(-\frac{E_F - E_v}{KT}\right)$ $N_v$: effective density of states in valence band. Intrinsic Carrier Concentration ($n_i$): For intrinsic semiconductors, $n_e = n_h = n_i$. $n_i^2 = N_c N_v \exp\left(-\frac{E_g}{KT}\right)$ $n_i = \sqrt{N_c N_v} \exp\left(-\frac{E_g}{2KT}\right)$ Conductivity of Intrinsic Semiconductors Total current $I = I_e + I_h$. Conductivity $\sigma = e(n_e \mu_e + n_h \mu_h)$. $\mu_e$: electron mobility, $\mu_h$: hole mobility. P-N Junction Diode Formed by joining p-type and n-type semiconductors. Depletion Region: Region near the junction depleted of free charge carriers, containing immobile ions. Potential Barrier ($V_0$): Voltage across the depletion region, opposes further diffusion. Forward Bias: Positive voltage applied to p-side, negative to n-side. Reduces barrier, current flows. Reverse Bias: Negative voltage applied to p-side, positive to n-side. Increases barrier, very small current flows. Diode Current Equation: $I = I_0 \left(e^{\frac{eV}{\eta V_T}} - 1\right)$. Thermistor Special resistor whose resistance changes significantly with temperature. Working Principle: Resistance decreases as temperature increases (for NTC type). High sensitivity. Types: Positive Temperature Coefficient (PTC): Resistance increases with temperature. Applications: Timers, heaters, circuit protection. Negative Temperature Coefficient (NTC): Resistance decreases with temperature. Applications: Temperature measurement, control, automotive, consumer appliances. Hall Effect Principle: When a current-carrying conductor/semiconductor is placed in a perpendicular magnetic field, a voltage (Hall voltage, $V_H$) is generated perpendicular to both current and magnetic field. Hall Voltage: $V_H = \frac{IB}{nqW}$ Hall Coefficient ($R_H$): $R_H = \frac{1}{nq}$ (for electrons); $R_H = \frac{1}{pq}$ (for holes). Applications: Determine semiconductor type (n or p). Measure carrier concentration ($n$ or $p$). Calculate mobility of charge carriers ($\mu$). Measure magnetic field strength. Dielectric Materials Introduction to Dielectrics Insulating materials that can store electrical energy when placed in an electric field. Contain tightly bound electrons, no free charge carriers. Can be solid, liquid, or gas. Examples: Glass, mica (solid); transformer oil (liquid); air (gas). Polar vs. Non-Polar Dielectrics Non-Polar Dielectrics: No permanent dipole moment in absence of E-field (e.g., O$_2$, N$_2$). Polar Dielectrics: Possess permanent dipole moment even in absence of E-field, but random orientation (e.g., HCl, H$_2$O). Polarization and Polarizability Electric Dipole: Equal positive and negative charges separated by a small distance. Dipole Moment ($\mu_e$): Product of charge magnitude and separation distance. Polarization ($\mathbf{P}$): Dipole moment per unit volume. Arises when an E-field is applied. Polarizability ($\alpha$): Constant of proportionality between induced dipole moment and E-field ($\mu = \alpha E$). Total Polarization $\mathbf{P} = N\alpha\mathbf{E}$ ($N$: number of particles per unit volume). Types of Polarisations Electronic Polarization ($P_e$): Displacement of electron cloud relative to nucleus. Occurs fastest (optical frequencies, $10^{15} \text{ Hz}$). Independent of temperature. Expression for Electronic Polarizability: $\alpha_e = 4\pi\epsilon_0 R^3$. ($R$: atomic radius). Ionic Polarization ($P_i$): Displacement of cations and anions in opposite directions in ionic solids. Slower than electronic (infrared frequencies, $10^{13} \text{ Hz}$). Independent of temperature. Orientation Polarization ($P_o$): Alignment of permanent dipoles in polar molecules with the E-field. Slowest (audio frequencies, $10^6 - 10^{10} \text{ Hz}$). Highly dependent on temperature ($P_o \propto 1/T$). Space Charge Polarization ($P_s$): Diffusion of ions over macroscopic distances, leading to charge redistribution. Usually negligible in common dielectrics. Total Polarization: $P = P_e + P_i + P_o + P_s$. Frequency and Temperature Dependence of Polarization Electronic & Ionic: Independent of temperature. Orientation & Space Charge: Dependent on temperature (Orientation $\propto 1/T$). Frequency Dependence: At low frequencies, all polarizations contribute. As frequency increases, slower mechanisms (orientation, then ionic) "drop out" as dipoles cannot reorient fast enough. At optical frequencies, only electronic polarization remains significant. Determination of Dielectric Constant (Schering Bridge Method) Used to measure capacitance and relative permittivity. Balances an unknown capacitance against known capacitors and resistors. At balance, $C_1 = C_2 \frac{R_4}{R_3}$. Dielectric constant $\epsilon_r = C'_1 / C_1$ ($C'_1$: capacitance with dielectric, $C_1$: capacitance without). Ferroelectricity Crystalline dielectric materials exhibiting spontaneous polarization (permanent electric dipole moment) even without an applied E-field. Exhibits dielectric hysteresis (P-E loop). Becomes paraelectric above its Curie temperature ($T_C$). Examples: Barium Titanate (BaTiO$_3$), Potassium Dihydrogen Phosphate (KDP). Barium Titanate (BaTiO$_3$) Above $120^\circ\text{C}$ ($T_C$), it has a cubic structure (paraelectric). Below $120^\circ\text{C}$, it transforms to a tetragonal phase, where the Ti ion shifts, creating a net dipole moment (ferroelectric). Applications of Ferroelectric Materials Capacitors (high capacitance). Memory cores in computers. Piezoelectric devices (transducers, microphones, gas lighters). Pyroelectric devices (infrared detectors). Optical modulators. Frequency stabilizers, crystal oscillators. Applications of Dielectric Materials Dielectric medium in capacitors. Insulating materials in transformers, cables (PVC). Dielectric heating (microwave ovens, industrial heating).