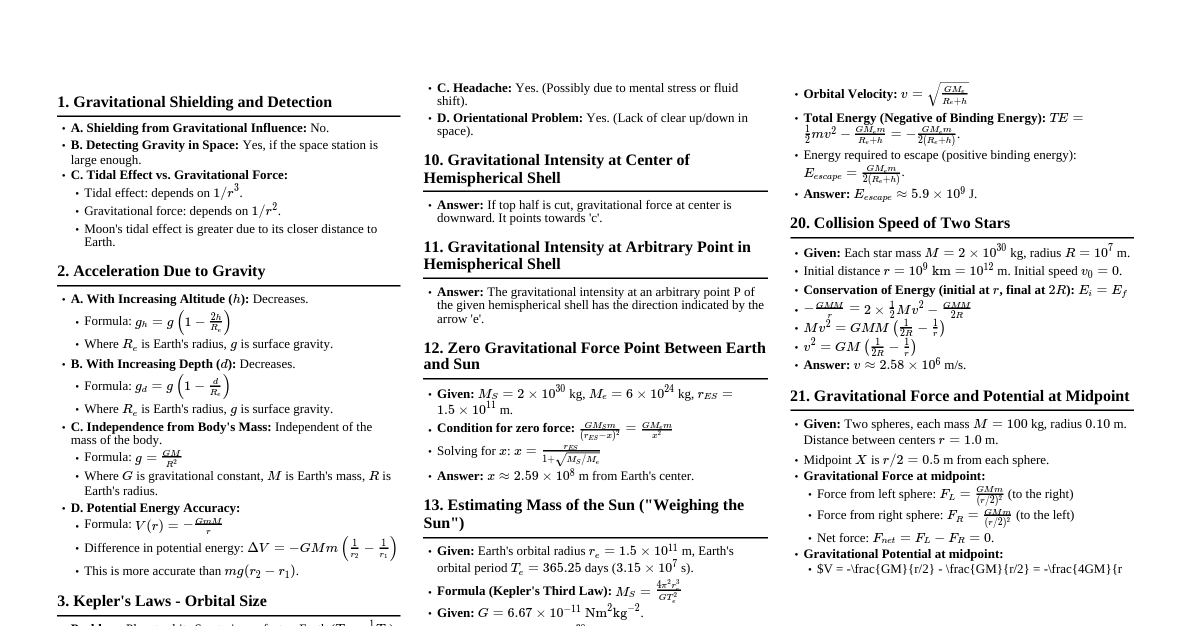

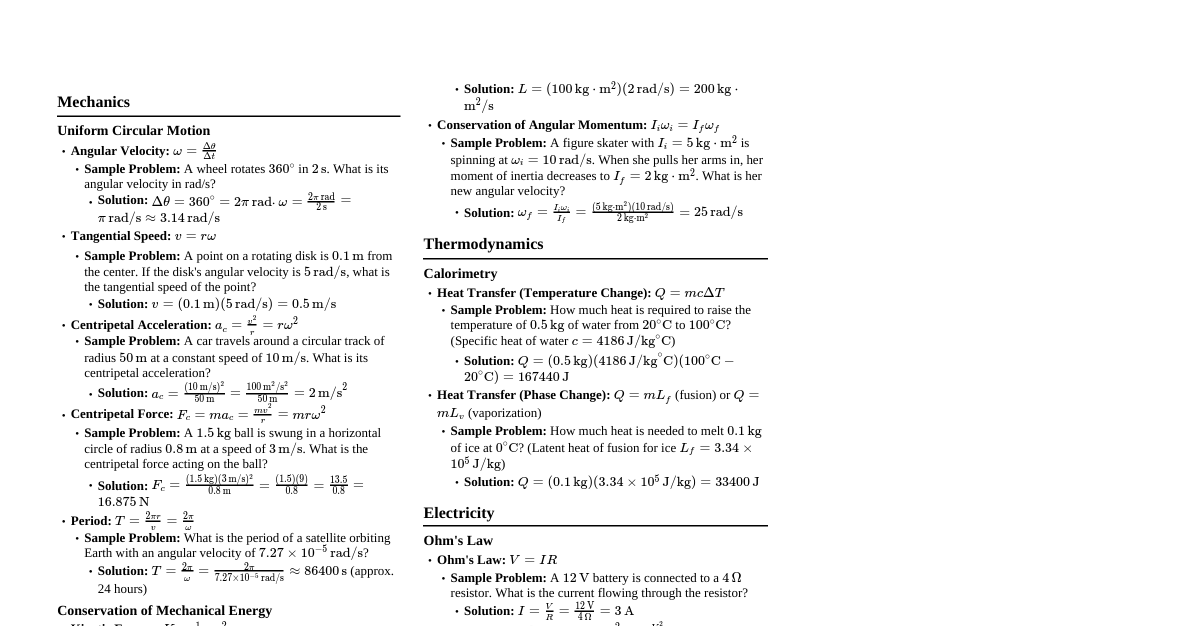

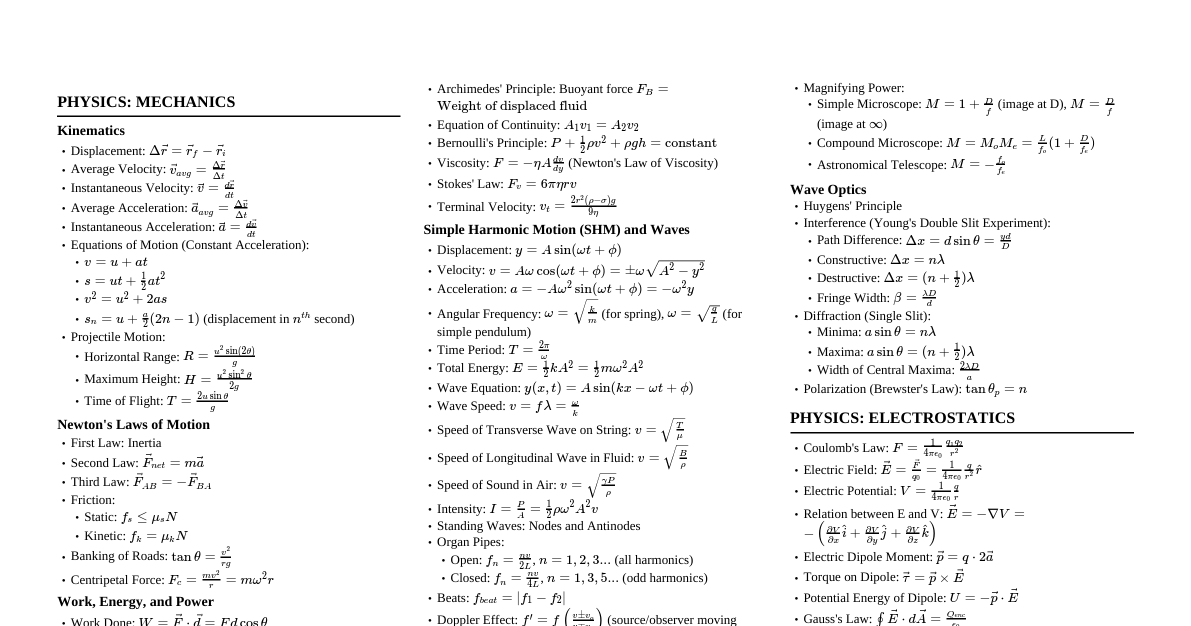

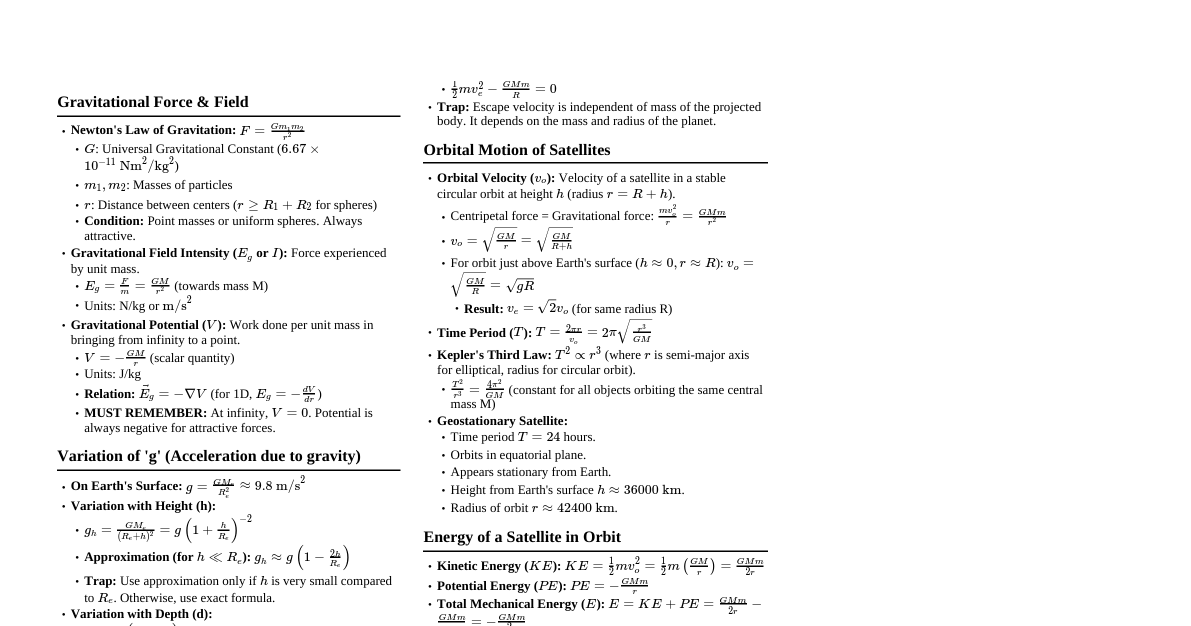

1. Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation Key Concept What it is: Describes the attractive force between any two objects with mass. It's a fundamental force. Formula: $F = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}$ $G$: Gravitational constant, a tiny number ($6.674 \times 10^{-11}$). This means gravity is very weak unless masses are huge. $m_1, m_2$: Masses of the two objects. $r$: Distance between the *centers* of the two objects. Inverse Square Law: The force gets much weaker as distance increases. Double the distance, force becomes $1/4$. Study Tips Remember $r$ is center-to-center. For Earth and a satellite, it's $R_{Earth} + \text{altitude}$. Practice problems where you change $m$ or $r$ and see how $F$ changes. Don't forget the units for $G$. Example If the distance between two objects is halved, how does the gravitational force between them change? Original: $F_1 = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}$. New distance: $r/2$. New force: $F_2 = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{(r/2)^2} = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2/4} = 4 G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} = 4 F_1$. The force becomes 4 times stronger. 2. Gravitational Field Strength ($g$) Key Concept What it is: It's basically the acceleration due to gravity. It tells you how strong gravity is at a certain point, without needing to know the mass of the object *feeling* the gravity. Formula 1 (general): $g = \frac{F}{m_{test}}$ (Force per unit test mass). Formula 2 (for a massive body M): $g = G \frac{M}{r^2}$ $M$: Mass of the *source* of the gravitational field (e.g., Earth). $r$: Distance from the center of $M$. On Earth's surface: $g \approx 9.81 \, \text{m/s}^2$. This value changes slightly with altitude. Study Tips Notice the similarity between $g = G \frac{M}{r^2}$ and $F = G \frac{M m}{r^2}$. If you multiply $g$ by a small mass $m$, you get the force $F$ on that mass. Understand that $g$ is a vector quantity (points towards the center of the massive body), though we often deal with its magnitude. Example What is the value of $g$ at an altitude where $r$ is twice Earth's radius ($2R_E$)? At surface: $g_{surface} = G \frac{M_E}{R_E^2}$. At altitude: $g_{alt} = G \frac{M_E}{(2R_E)^2} = G \frac{M_E}{4R_E^2} = \frac{1}{4} g_{surface}$. So, $g$ is one-fourth the value on the surface. 3. Gravitational Potential Energy (GPE) Key Concept What it is: Energy stored in a system of masses due to their positions in a gravitational field. It represents the work done to bring the masses to their current positions. Formula: $U = -G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r}$ The negative sign is crucial! It means gravity is an attractive force. $U$ is defined as zero when objects are infinitely far apart ($r \to \infty$). Since gravity is attractive, you need to *do work* to pull objects apart, increasing their potential energy towards zero. Study Tips The negative sign often confuses people. Just remember: more negative $U$ means a stronger, more bound system (like a planet orbiting a star). Less negative (closer to zero) means they are further apart and less bound. GPE is a scalar (just a number, no direction). Conservation of Energy: $KE_i + U_i = KE_f + U_f$. Use this for problems involving motion in gravity. Example Why is GPE negative? Because we define $U=0$ at infinite separation. Since gravity is attractive, energy must be *released* (or work done *by* gravity) as objects get closer. This means their potential energy decreases from zero, becoming negative. It represents a "debt" of energy that must be paid to separate them. 4. Gravitational Potential ($\Phi$) Key Concept What it is: Similar to gravitational field strength, but for potential energy. It's the potential energy per unit mass at a point. It describes the "energy landscape" of gravity. Formula: $\Phi = \frac{U}{m_{test}} = -G \frac{M}{r}$ $M$: Mass of the source creating the potential. $r$: Distance from the center of $M$. Like GPE, it's typically negative and zero at infinity. Study Tips Think of it like elevation on a map: lower elevation means lower potential. Objects naturally "fall" to lower potential. If you know $\Phi$ at a point, multiplying by a mass $m$ gives you the GPE of that mass at that point: $U = m\Phi$. Example Two points, A and B, have gravitational potentials $\Phi_A = -10 \, \text{J/kg}$ and $\Phi_B = -5 \, \text{J/kg}$. If you release a 2 kg object at rest at point B, will it move towards A or away from A? Point A has a lower (more negative) potential than point B. Objects tend to move towards lower potential. So, the 2 kg object will move towards point A. 5. Escape Speed ($v_e$) Key Concept What it is: The minimum speed an object needs to break free from a massive body's gravity and never fall back. It's about having enough kinetic energy to overcome the negative gravitational potential energy. Formula: $v_e = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{R}}$ $M$: Mass of the body you're escaping from. $R$: Radius of that body (where the object starts). Derived from conservation of energy: $KE_{initial} + U_{initial} = KE_{final} + U_{final}$. For escape, $KE_{final}$ and $U_{final}$ are both 0 (at infinity, just barely stopped). Study Tips Don't confuse escape speed with orbital speed. Escape speed means leaving forever; orbital speed means staying in a loop. The escape speed does NOT depend on the mass of the escaping object. A feather and a rocket have the same escape speed from Earth. Example Why is the escape speed from Earth so much higher than from the Moon? Because Earth has a much larger mass ($M$) and a larger radius ($R$) than the Moon. While both affect the value, Earth's significantly larger mass dominates, leading to a much stronger gravitational pull and thus a higher escape speed required. 6. Orbits and Circular Motion in Gravity Key Concept What it is: How objects move around a central body under gravity. For circular orbits, the gravitational force acts as the centripetal force. Balance of forces: $F_{grav} = F_{centripetal} \implies G \frac{Mm}{r^2} = \frac{mv^2}{r}$ $M$: Mass of the *central* body (e.g., Earth). $m$: Mass of the *orbiting* body (e.g., satellite). $r$: Orbital radius (distance from center of $M$). Orbital Speed ($v$): $v = \sqrt{\frac{GM}{r}}$ (Note: $m$ cancels out!) Orbital Period ($T$): $T = 2\pi \sqrt{\frac{r^3}{GM}}$ (Time for one full orbit). Geosynchronous Orbit: Special orbit where $T = 24$ hours, so a satellite stays above the same point on Earth's equator. Study Tips Notice that orbital speed depends only on the central mass $M$ and the orbital radius $r$, not the satellite's mass $m$. Memorize the relationship $T = \frac{2\pi r}{v}$ to connect period and speed. Be careful with $r$: it's the distance from the *center* of the Earth, not just the altitude. Example An astronaut pushes a small satellite out of the International Space Station (ISS) in the direction of its orbit. Will the satellite immediately fall to Earth? No. The ISS and the satellite are already in orbit, meaning they have the necessary orbital speed. Pushing it slightly won't make it fall, it will simply change its orbit slightly (perhaps making it elliptical or raising/lowering its altitude slightly). They are both already "falling" around the Earth. 7. Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion Key Concept These laws describe how planets (or satellites) orbit. Newton's Law of Gravitation *explains* Kepler's Laws. 1st Law (Ellipses): Orbits are not perfect circles, but ellipses, with the central body at one focus. 2nd Law (Equal Areas): Planets sweep out equal areas in equal times. Implication: planets move faster when closer to the Sun (or central body) and slower when farther away. 3rd Law (Periods and Radii): $T^2 \propto a^3$ (or $T^2/a^3 = \text{constant}$). $T$: Orbital period. $a$: Semi-major axis (for circles, this is just the radius $r$). The constant is $\frac{4\pi^2}{GM_{central}}$. This means the constant is the same for all objects orbiting the *same* central mass. Study Tips Understand the qualitative meaning of the first two laws (ellipses, varying speed). The 3rd Law is quantitative. Practice using it to find unknown periods or distances. Remember the constant in the 3rd Law depends on the mass of the *central* body. Example Planet X is 4 times farther from its star than Planet Y. How much longer is Planet X's orbital period compared to Planet Y's? From Kepler's 3rd Law: $T^2 \propto a^3$. So, $T_X^2 / T_Y^2 = a_X^3 / a_Y^3$. Given $a_X = 4a_Y$. So, $T_X^2 / T_Y^2 = (4a_Y)^3 / a_Y^3 = 64 a_Y^3 / a_Y^3 = 64$. Therefore, $T_X^2 = 64 T_Y^2 \implies T_X = \sqrt{64} T_Y = 8 T_Y$. Planet X's period is 8 times longer.