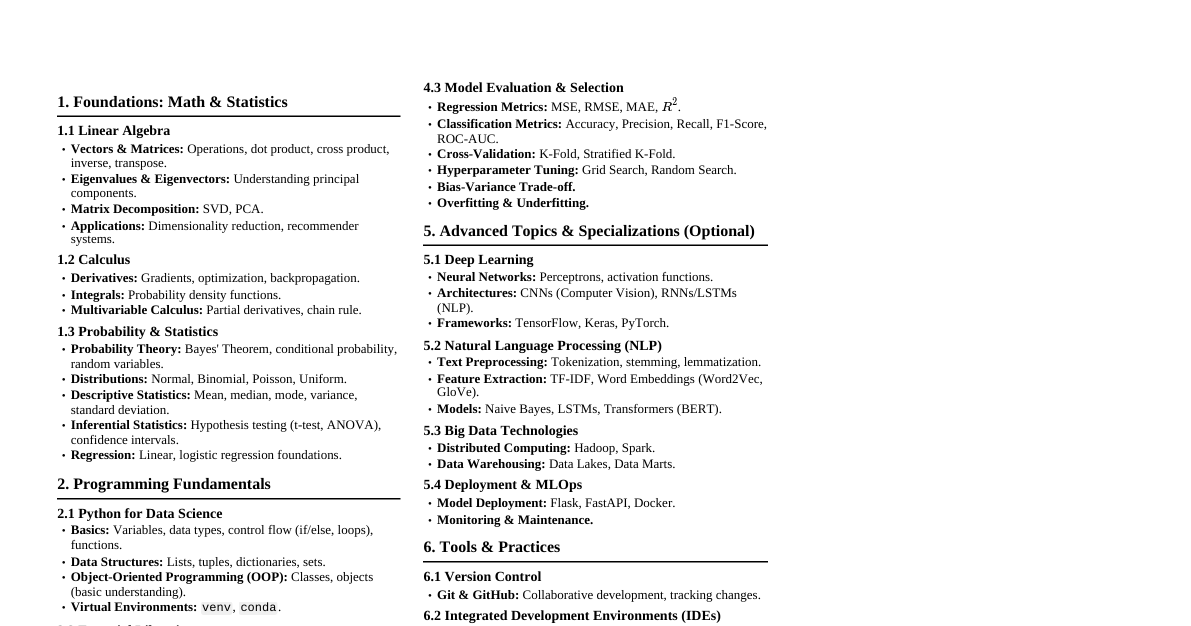

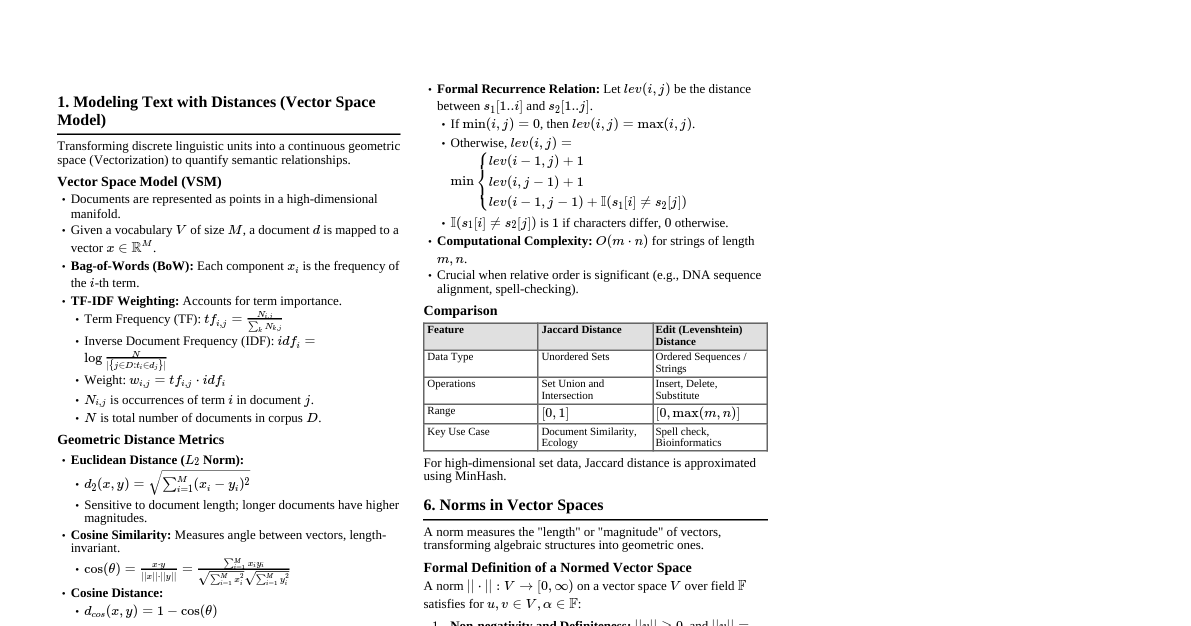

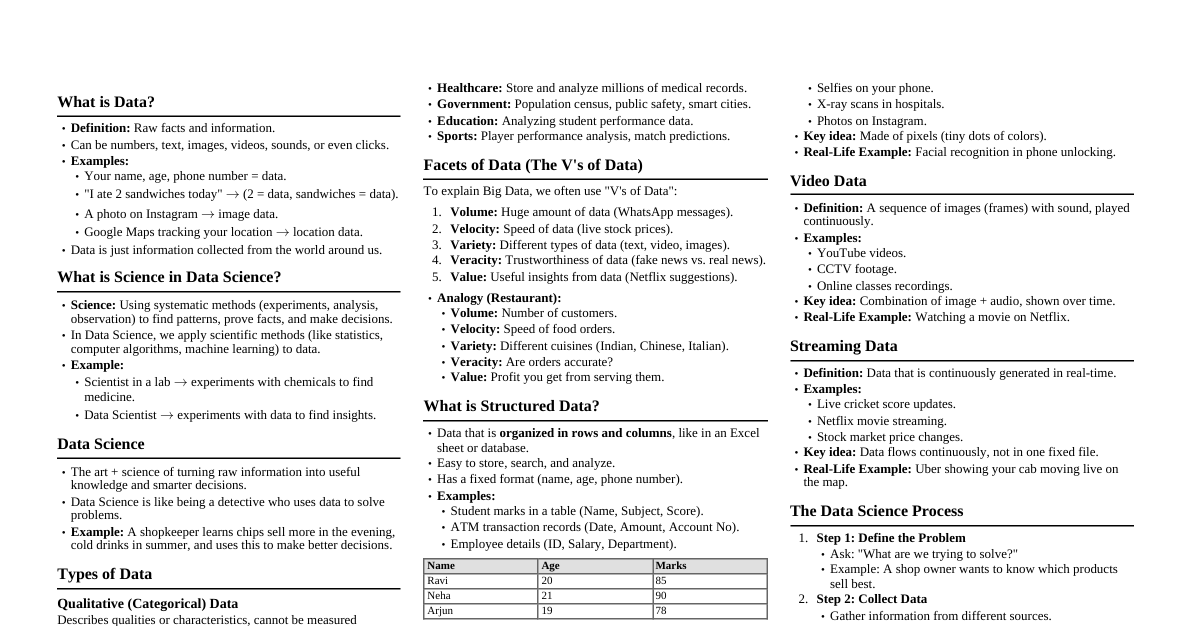

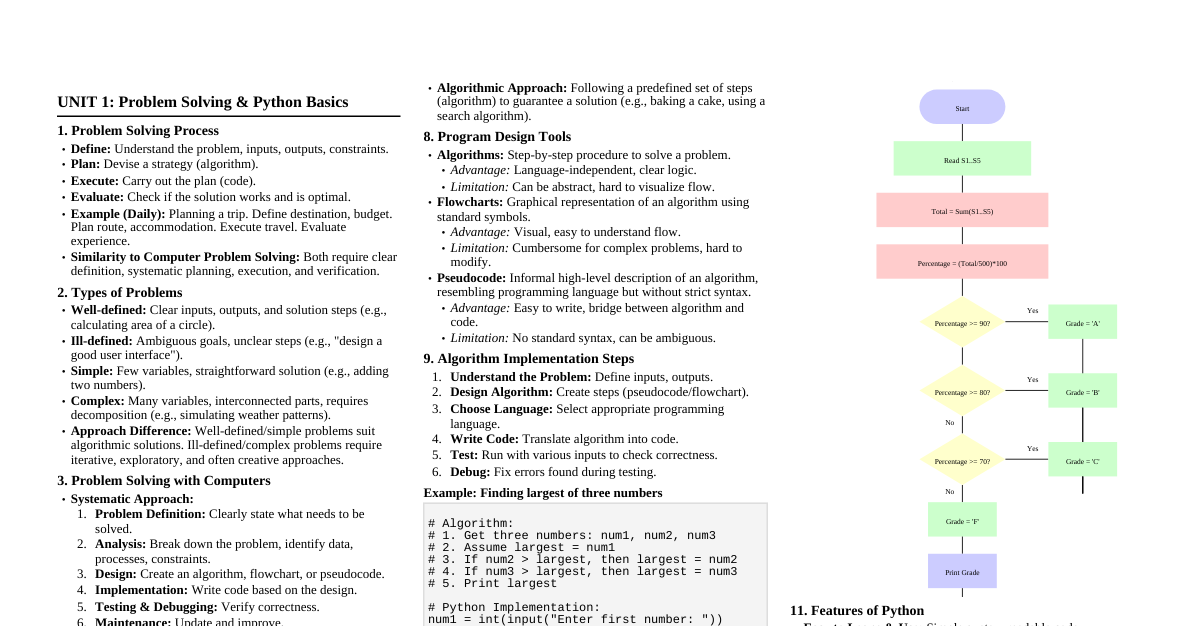

1. Logistic Regression & Classification 1.1. Model Behavior Logistic Function: $P(Y=1) = \frac{e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X}}{1 + e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X}} = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(\beta_0 + \beta_1 X)}}$ Log-Odds: $\ln \left( \frac{P(Y=1)}{1 - P(Y=1)} \right) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X$ Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) Loss: $L(\beta) = -\sum_i [y_i \log(p_i) + (1-y_i) \log(1-p_i)]$ Logistic regression minimizes BCE (MLE $\Leftrightarrow$ minimize -log-likelihood). With L2: minimize BCE + $\lambda||\beta||^2$. Gradient intuition: if $y=1 \rightarrow$ increase logit; if $y=0 \rightarrow$ decrease logit. Interpretation of $\beta_1$: A one-unit change in $X$ is associated with an $e^{\beta_1}$ change in the odds that $Y=1$. Decision Boundary (Binary): For $P(Y=1) = 0.5$, the log-odds are $0$, so $\beta_0 + \beta_1 X = 0$. This implies a linear decision boundary. Nonlinear Decision Boundaries Logistic regression is linear in the features, not necessarily in the raw inputs. To get nonlinear boundaries, add nonlinear features, e.g.: $X=\{X_1, X_2, X_1^2, X_2^2, X_1X_2\}$ Example: adding squared terms creates circular/elliptical boundaries. Micro-Examples (Interpretation) Odds interpretation: If $\beta_1 = 0.7$, then each 1-unit increase in $X$ multiplies the odds of $Y=1$ by $e^{0.7} \approx 2.01$. $\rightarrow$ Odds roughly double per unit of $X$. Probability example: For $\beta_0 = -3, \beta_1 = 1, X = 2$: $p = \frac{e^{-3+2}}{1+e^{-3+2}} = \frac{e^{-1}}{1+e^{-1}} \approx 0.27$. $\rightarrow$ Even with a positive slope, the intercept can keep probabilities low. Sign interpretation: $\beta_1 Class boundary: If $P = 0.5$ at decision boundary, $\beta_0 + \beta_1 X = 0 \Rightarrow X = -\beta_0 / \beta_1$. Example: $\beta_0 = -2, \beta_1 = 0.5 \rightarrow$ boundary at $X = 4$. Regularization Adding a penalty term to the negative log-likelihood (Binary Cross-Entropy) loss: $$ \min_{\beta} \left( -\sum_i [y_i \log p_i + (1-y_i) \log(1-p_i)] + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^J \beta_j^2 \right) $$ (L2/Ridge shown; L1/LASSO uses $|\beta_j|$). Increasing $\lambda$ (penalty) $\rightarrow$ decreases coefficient magnitudes $\rightarrow$ reduces variance $\rightarrow$ increases bias. Micro-Examples (Regularization Effects) Coefficient shrinkage: If unregularized $\beta_1 = 4.0$ but with strong L2 penalty becomes $\beta_1 = 0.9 \rightarrow$ model becomes less sensitive to $X \rightarrow$ lower variance. Effect on predictions: Regularization tends to pull predictions toward 0.5 in logistic regression. Example: Unregularized $\hat{p} = 0.96$ becomes $\hat{p} = 0.78$ after L2 penalty. L1 sparsity: With LASSO, insignificant coefficients become exactly 0. Example: $\beta_2 = 0.07 \rightarrow$ becomes 0 at $\lambda = 0.5$. 1.2. Multiclass Logistic Regression Multinomial Logit (One-vs-Rest): Fits $K$ independent logistic regression models, one for each class $k$ against "rest" ($Y \neq k$). $$ \ln \left( \frac{P(Y=k)}{P(Y \neq k)} \right) = \beta_{0,k} + \beta_{1,k}X_1 + \dots + \beta_{p,k}X_p $$ Softmax Function: Converts raw scores from multiclass models into probabilities that sum to 1. $$ P(y=k|\vec{x}) = \frac{e^{\vec{x}^T \hat{\beta}_k}}{\sum_{j=1}^K e^{\vec{x}^T \hat{\beta}_j}} $$ OvR vs Multinomial (Softmax) Method How it Works Boundaries OvR Fit K binary models: class k vs rest K independent linear boundaries (may overlap) Multinomial Single joint loss using softmax Coupled boundaries; probabilities sum to 1 Softmax chooses class k by maximizing: $\exp(x^T\beta_k)$. 1.3. Classification Metrics Confusion Matrix: Predicted Low High True Low True Negative (TN) False Positive (FP) True High False Negative (FN) True Positive (TP) Thresholding: Changing classification threshold $\pi$ (e.g., $P(Y=1) \ge \pi$) affects FP/FN rates. Lower $\pi \rightarrow$ more positives predicted $\rightarrow$ higher TP, higher FP, lower FN. Higher $\pi \rightarrow$ fewer positives predicted $\rightarrow$ lower TP, lower FP, higher FN. ROC Curve: Plots True Positive Rate (TPR) vs. False Positive Rate (FPR) for all possible thresholds. TPR (Recall): $\frac{TP}{TP + FN}$ FPR: $\frac{FP}{FP + TN}$ A good model is closer to the top-left corner (high TPR, low FPR). AUC Interpretation: AUC = P(model ranks a random positive > random negative). Threshold-invariant measure of separability. High AUC = better ranking ability even if threshold changes. F1 Score: $2 \cdot \frac{\text{Precision} \cdot \text{Recall}}{\text{Precision} + \text{Recall}}$. Useful for imbalanced datasets. === SUMMARY BOX: Logistic Regression === $\beta > 0 \rightarrow$ probability of $Y=1$ increases; $\beta $e^\beta = $ multiplicative change in odds for 1-unit increase in $X$. Large $|\beta| \rightarrow$ strong effect; small $\beta \rightarrow$ weak effect. Decision boundary when $\beta_0 + \beta_1X = 0$ ($P = 0.5$). Multicollinearity inflates coefficient variance $\rightarrow$ unstable estimates. Imbalanced data $\rightarrow$ default threshold 0.5 may perform poorly. Regularization shrinks coefficients $\rightarrow$ reduces variance, increases bias. === SUMMARY BOX: Regularization === L2 (Ridge): shrinks coefficients toward 0, never to exactly 0. L1 (LASSO): sets some coefficients exactly to 0 $\rightarrow$ feature selection. Increasing $\lambda$ increases bias, decreases variance. Penalizes large coefficients $\rightarrow$ more stable model. Larger $\lambda \rightarrow$ simpler decision boundary, underfitting risk. Ridge useful with high-dimensional or multicollinear features. === Regularization & Decision Boundaries === As $\lambda \rightarrow \infty$ in logistic regression: $\beta \rightarrow 0$ Decision boundary becomes flatter / less steep Predictions collapse toward class prior ($\approx$ constant) === Multinomial Logit Interpretation === $\beta_{j,k}$ = change in log-odds of choosing class k over baseline class K. Decision boundaries are linear but COUPLED across classes. One-vs-Rest $\rightarrow$ K independent boundaries (may overlap). Multinomial Softmax $\rightarrow$ coordinated boundaries; probabilities sum to 1. 7. When to Use What Tables 7.1. Model Selection Quick Table Situation Best Model / Approach High-dimensional features ($p \gg n$) Logistic/linear regression with L1 (LASSO) or L2 (Ridge) Complex nonlinear patterns Decision Trees, Random Forest, Boosting Strong interaction effects Trees or Random Forest (automatic interaction handling) Very small dataset Logistic/linear regression, Naive Bayes High variance model Bagging, Random Forest High bias model Boosting (Gradient Boosting, AdaBoost) Need interpretability Logistic/linear models, shallow trees Highly imbalanced classes Adjust threshold, ROC/AUC, F1, class weighting 2. Bayesian Inference 2.1. Concepts Bayes' Theorem: $P(\theta|Y) = \frac{P(Y|\theta)P(\theta)}{P(Y)}$ $P(\theta|Y)$: Posterior (updated belief about parameter $\theta$ given data $Y$) $P(Y|\theta)$: Likelihood (probability of data $Y$ given parameter $\theta$) $P(\theta)$: Prior (initial belief about parameter $\theta$) $P(Y)$: Marginal Likelihood (normalizing constant) Conjugate Priors: If the posterior distribution is in the same family as the prior distribution, the prior is conjugate. Bernoulli likelihood + Beta prior $\rightarrow$ Beta posterior. Gaussian likelihood + Gaussian prior $\rightarrow$ Gaussian posterior (for mean). Posterior Mean: For Beta-Binomial, $\hat{p}_{PM} = \frac{a_0 + \sum y_i}{a_0 + b_0 + n}$. Weighted average of prior mean and sample proportion. Effect of n: As $n$ (sample size) increases, the effect of the prior on the posterior estimate decreases. 2.2. Hierarchical Models Models where parameters themselves have probability distributions (priors with hyperparameters). $$ Y_{ij}|\alpha_j, \beta_1, X_{1,ij} \sim \text{Bernoulli} \left( \ln \frac{p_{ij}}{1-p_{ij}} = \alpha_j + \beta_1 X_{1,ij} \right) $$ $$ \alpha_j \sim \mathcal{N}(\alpha_0, \sigma_\alpha^2) $$ Useful for clustered/grouped data (e.g., shots by player). Allows "borrowing strength" across groups. Random Intercepts ($\alpha_j$): Each group has its own intercept, drawn from a common distribution. Random Slopes ($\beta_j$): Each group has its own slope, drawn from a common distribution. Posterior Predictive Value: Integrates over the posterior distribution of parameters to predict new observations. $$ P(\tilde{Y}|Y) = \int_\theta P(\tilde{Y}|\theta) P(\theta|Y) d\theta $$ 2.3. MCMC (Markov Chain Monte Carlo) Purpose: To sample from complex (non-analytical) posterior distributions. Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm: Start at current state $\theta^{(t)}$. Propose new state $\theta^*$ from proposal distribution $q(\cdot|\theta^{(t)})$. Calculate acceptance probability $a = \min \left(1, \frac{P(\theta^*|Y) q(\theta^{(t)}|\theta^*)}{P(\theta^{(t)}|Y) q(\theta^*|\theta^{(t)})} \right)$. Accept $\theta^*$ with probability $a$; otherwise, $\theta^{(t+1)} = \theta^{(t)}$. Pymc Results: Provides sampled posterior distributions, posterior means, standard deviations, and credible intervals. 7.5. Bayesian vs Frequentist Decision Table Situation Preferred Approach Need explicit uncertainty about parameters Bayesian (posterior distribution) Have strong prior knowledge from past data or theory Bayesian Small datasets $\rightarrow$ need regularization from priors Bayesian Large datasets, computation expensive Frequentist (MLE, quick optimization) Model has conjugate priors $\rightarrow$ easy computation Bayesian High-dimensional models without easy priors Frequentist (regularized regression) Want simple hypothesis tests, p-values Frequentist MCMC or sampling computationally feasible Bayesian === SUMMARY BOX: Bayesian Inference === Posterior $\propto$ Likelihood $\times$ Prior. Prior matters most when $n$ is small; as $n \rightarrow \infty$, likelihood dominates. Conjugate priors $\rightarrow$ closed-form posterior (Beta-Binomial, Normal-Normal). Posterior predictive integrates over parameter uncertainty. Hierarchical models “borrow strength” across groups. MCMC used when posterior lacks closed-form solution. Credible interval = probability statement about parameter. === Bayesian vs Frequentist Examples === Frequentist example: "Estimate $\beta$ by maximizing likelihood (MLE)." Bayesian example: "Prior: $\beta \sim N(0,1)$. Posterior shrinks toward prior when $n$ is small." Hierarchical example: "Group-level intercepts $\alpha_j$ shrink toward population mean $\mu_\alpha$." 3. Decision Trees 3.1. Classification Trees Geometry: Partitions feature space with axis-parallel lines/hyperplanes. Splitting Criteria: Selects predictor and threshold to maximize "purity" gain (reduce "impurity"). Gini Index: $1 - \sum_k (\text{Proportion of Class } k \text{ in Region } r)^2$. Favors larger partitions. Entropy: $-\sum_k (\text{Proportion of Class } k \text{ in Region } r) \log_2 (\text{Proportion of Class } k \text{ in Region } r)$. Penalizes impurity more. Classification Error: $1 - \max_k (\text{Proportion of Class } k \text{ in Region } r)$. Least sensitive to impurity. $$ \text{Gain}(R) = m(R) - \frac{N_1}{N}m(R_1) - \frac{N_2}{N}m(R_2) $$ ($m$ is impurity measure, $N$ is number of samples). Stopping Conditions: Prevents overfitting. Max depth, min samples per leaf, min impurity decrease. Increasing tree depth $\rightarrow$ lower bias, higher variance. Micro-Examples (Classification Trees) Impurity change: Parent node has 8 positives, 2 negatives: Gini = $1 - (0.8^2 + 0.2^2) = 0.32$. Split into: Left: 4 pos, 1 neg (Gini = 0.32); Right: 4 pos, 1 neg (Gini = 0.32). $\rightarrow$ No impurity reduction $\rightarrow$ bad split. Identical X values with opposite labels: If $X = 3$ occurs for $Y = 0$ and $Y = 1 \rightarrow$ tree cannot achieve zero training error, even with infinite depth. 3.2. Regression Trees Splitting Criteria: Minimizes Mean Squared Error (MSE) in child nodes. $$ \min_{p, t_p} \left( \frac{N_1}{N}\text{MSE}(R_1) + \frac{N_2}{N}\text{MSE}(R_2) \right) $$ Prediction: Average of response values in the leaf node. Numerical vs. Categorical Attributes: Numerical splits on value; categorical splits on categories (one-hot encoding is common). Micro-Examples (Regression Trees) Leaf prediction: Values in leaf: $[10, 12, 14] \rightarrow$ prediction = 12. MSE split decision: Parent MSE = variance = 9. Split produces children MSE = 4 and 1. Weighted average = 2.5. $\rightarrow$ Good split (reduces error). 3.3. Pruning Motivation: Grow a complex tree first, then prune to find a simpler, more generalizable tree. Cost Complexity Pruning: $C(T) = \text{Error}(T) + \alpha |T|$ $|T|$: number of leaves in the tree. $\alpha$: complexity parameter. Increasing $\alpha \rightarrow$ simpler tree (higher bias, lower variance). Cross-validation is used to select the optimal $\alpha$. === SUMMARY BOX: Decision Trees === Deep tree $\rightarrow$ low bias, high variance $\rightarrow$ overfits. Shallow tree $\rightarrow$ high bias, low variance $\rightarrow$ underfits. Good split = largest impurity reduction (classification) or MSE reduction (regression). Trees handle nonlinearity & interactions automatically. Cannot achieve zero training error if identical X have different labels. Pruning reduces variance by simplifying tree. Bagging decorrelates instability; boosting reduces bias. === Which Tree/Ensemble to Use === Shallow tree $\rightarrow$ high bias, low variance. Deep tree $\rightarrow$ low bias, high variance. Bagging $\rightarrow$ reduces variance, no bias change. Random Forest $\rightarrow$ reduces variance more (decorrelates trees). Boosting $\rightarrow$ reduces bias, may increase variance. AdaBoost $\rightarrow$ focuses on hard-to-classify cases; uses weighted stumps. === Random Forest Hyperparameters === Increase n_estimators $\rightarrow \downarrow$ variance (always helps). Increase max_features $\rightarrow \uparrow$ correlation between trees $\rightarrow \uparrow$ variance. Decrease max_depth $\rightarrow \uparrow$ bias, $\downarrow$ variance. Increase min_samples_leaf $\rightarrow$ smoother model, $\downarrow$ variance. Bootstrap = ON $\rightarrow$ essential for variance reduction. 4. Missingness 4.1. Types of Missingness MCAR (Missing Completely at Random): Probability of missingness is independent of observed or unobserved data. (e.g., random data entry error) MAR (Missing at Random): Probability of missingness depends only on observed data. (e.g., men less likely to answer health survey) MNAR (Missing Not at Random): Probability of missingness depends on unobserved data. (e.g., sicker people skip health survey due to severity) Micro-Examples (Missingness Types & Effects) MCAR example: Sensor randomly fails 5% of the time. Missingness unrelated to $X$ or $Y$. $\rightarrow$ Complete-case analysis is unbiased. MAR example: Older patients less likely to report income $\rightarrow$ missingness depends on age (observed). $\rightarrow$ Can be corrected with models using age. MNAR example: People with high income choose not to report income $\rightarrow$ missingness depends on income itself. $\rightarrow$ Cannot be fixed with observed data only. 7.3. Missingness Type Decisions Missingness Type Definition What to Do / Best Approach MCAR Missingness independent of observed + unobserved values Simple methods OK: mean/median, listwise deletion unbiased MAR Missingness depends only on observed variables Model-based imputation, multiple imputation, regression/kNN MNAR Missingness depends on unobserved values Cannot be solved with data alone; requires modeling missingness mechanism or external info Hint for exams: If missingness depends on itself $\rightarrow$ MNAR Exam Trigger Rule: If missingness depends on the value itself $\rightarrow$ MNAR. (e.g., people with high income refuse to report income) 4.2. Imputation Methods Mean/Median/Mode Imputation: Replaces missing values with the mean/median (quantitative) or mode (categorical) of the observed values. (Simple, but reduces variance, distorts relationships). Missing Indicator: Creates a binary variable indicating missingness, and often imputes the mean/mode in the original variable. Hot Deck Imputation: Randomly selects an observed value from a similar record. Model-Based Imputation: Predicts missing values using a model trained on other observed predictors. Deterministic: Plugs in $\hat{y}$ (can reduce uncertainty too much). Stochastic: Plugs in $\hat{y} + \epsilon$ (adds randomness to preserve variance). Iterative Imputation: For multiple variables with missingness, models each variable based on others, iterating until convergence. Micro-Examples (Imputation Behavior) Mean imputation shrinks variance: Original data: $[1, 2, 8, 9]$ (std $\approx 4$). Missing replaced with mean (5) $\rightarrow$ variance decreases. Regression imputation distorts distribution: Imputed values fall exactly on regression line $\rightarrow$ too narrow distribution. Hot deck: Missing value for "age" randomly chosen from similar row (same gender). 7.2. Imputation Method Selection Table Situation Best Imputation Method Data missing completely at random (MCAR) Mean/median imputation, listwise deletion acceptable Quantitative variable, linear relationships Regression imputation Categorical variable Mode imputation, hot deck Want to preserve variance Stochastic regression imputation, multiple imputation (MICE) Missingness related to other observed variables Model-based imputation, kNN imputation, MICE Missing indicator useful Add missingness indicator + simple imputation Many predictors with complex structure kNN imputation, iterative imputation Need fast/simple approach Mean/median for numeric, mode for categorical Key Consequences (Imputation) Mean/median imputation reduces variance + weakens correlations. Model-based (deterministic) imputation overstates certainty. Stochastic imputation preserves variance. MNAR cannot be solved using the observed data alone. === SUMMARY BOX: Missing Data & Imputation === MCAR: missingness unrelated to any variable $\rightarrow$ unbiased deletion OK. MAR: missingness depends on observed variables $\rightarrow$ model-based imputation works. MNAR: missingness depends on unobserved values $\rightarrow$ cannot fix with observed data only. Mean/median imputation reduces variance and weakens relationships. Regression imputation $\rightarrow$ overconfident predictions; stochastic version preserves variance. MICE/iterative imputation handles multiple variables with missingness. Missing indicator can help when missingness is informative. 5. Ensemble Methods 7.4. Ensemble Method Selection Table Goal / Situation Best Ensemble Method Reduce variance Bagging, Random Forest Reduce bias Boosting (Gradient Boosting, AdaBoost) High interpretability needed Bagging with shallow trees, linear meta-models When predictors are highly correlated Random Forest (feature subsampling decorrelates trees) Need best predictive accuracy Boosting or Stacking Want model flexibility + meta-learning Stacking (meta-model learns optimal combination) Small dataset but want ensembles Boosting (uses weak learners efficiently) Many weak but diverse models Stacking 5.1. Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) Concept: Reduces variance by training multiple models independently on bootstrap samples of the training data. Algorithm: Create $B$ bootstrap samples (sampling with replacement). Train a base model (e.g., Decision Tree) on each bootstrap sample. Aggregate predictions: Classification: Majority vote. Regression: Average of predictions. Behavior: Reduces variance, typically less susceptible to overfitting than single complex models. Often uses deep, unpruned trees. OOB (Out-of-Bag) Error: $\sim 37\%$ of samples are not selected in each bootstrap sample. Use these as a built-in validation set. OOB error $\approx$ unbiased estimate of test error. Eliminates need for a separate validation set. 5.2. Random Forest Concept: Modified bagging that decorrelates trees to further reduce variance. Modification: At each split in a decision tree, only a random subset of predictors is considered. Behavior: Further reduces variance compared to bagging by ensuring trees are less correlated. Why Feature Subsampling Helps: Prevents the same strong predictor from being chosen at every split. Reduces tree-to-tree correlation $\rightarrow$ reduces variance. RF = Bagging + Random Feature Selection. Hyperparameters: Number of trees, number of predictors to sample at each split, stopping criteria. Variable Importance: Mean Decrease Impurity (MDI): Sums impurity decreases across all splits a feature is used in. Can be biased towards high-cardinality features. Permutation Importance: Measures how much model performance decreases when a feature's values are randomly shuffled (breaking its relationship with the target). More robust. Micro-Examples (Bagging / RF Behavior) Bootstrap property: In a sample of size $n$, each bootstrap sample contains $\sim 63\%$ unique points. $\rightarrow 37\%$ are “out-of-bag” (OOB). Tree correlation example: If two features are highly predictive and always chosen, trees become correlated $\rightarrow$ bagging becomes less effective $\rightarrow$ RF fixes this by feature subsampling. 5.3. Boosting Concept: Sequentially builds models, each correcting errors of the previous one. Focuses on reducing bias. Gradient Boosting: Fit initial model $T_0$ to data. For $i = 1 \dots M$: Compute residuals $r_n = y_n - T_{i-1}(x_n)$. Fit new model $T_i$ to residuals. Update ensemble: $T \leftarrow T + \lambda T_i$ (where $\lambda$ is learning rate). Gradient Boosting Update Rule: $T_{new}(x) = T_{old}(x) + \lambda \cdot T^{(i)}(x)$. $T^{(i)}$ fits residuals: $r_i = y_i - T_{old}(x_i)$. $\lambda$ (learning rate) controls step size $\rightarrow$ small $\lambda$ = lower variance, slower learning. Behavior: Reduces bias, can be prone to overfitting if learning rate is too high or too many estimators are used. AdaBoost (Adaptive Boosting): Iteratively trains weak learners (stumps). Assigns higher weights to misclassified observations, forcing subsequent learners to focus on them. Combines weak learners with weights based on their accuracy. AdaBoost Weight Update: $w_n^{(t+1)} \propto w_n^{(t)} \cdot e^{-\alpha_t y_n h_t(x_n)}$. Misclassified points get larger weights $\rightarrow$ next stump focuses on them. Stump weight: $\alpha_t = \frac{1}{2} \ln \left( \frac{1 - \text{err}_t}{\text{err}_t} \right)$. Why Stumps Are Used: Stumps = high-bias, low-variance. Boosting reduces bias by combining many weak learners. Micro-Examples (Boosting Behavior) Residual update example: True $y = 10$, previous model predicts 7 $\rightarrow$ residual = 3 $\rightarrow$ next model fits 3. Learning rate effect: If learning rate = 1 $\rightarrow$ risk of overfitting quickly. If learning rate = 0.1 $\rightarrow$ slower learning but better generalization. === Boosting Failure Modes === Too many boosting rounds $\rightarrow$ overfitting. Learning rate too high $\rightarrow$ unstable, poor generalization. Base learners too deep $\rightarrow$ high variance, reduced interpretability. 5.4. Ensemble Stacking & Blending Blending: Trains diverse base models. A meta-model is then trained on a separate validation set using the base models' predictions as features. Pros: Flexible, meta-model learns optimal combination. Cons: Reduces data for meta-model training. Stacking: Similar to blending but uses K-fold cross-validation to generate out-of-sample predictions for the meta-model training. Algorithm: Split data into K folds. For each base model: For each fold $k$: train on $K-1$ folds, predict on fold $k$. Combine all out-of-sample predictions to form training data for the meta-model. Train base models on the full training set and predict on the test set for final meta-model input. Pros: Uses all data for base model training (via CV), meta-model training data has same size as original. Blending vs Stacking (Key Distinction): Blending: meta-model trained on holdout set (typically 10–20%). Stacking: meta-model trained on out-of-fold (OOF) predictions from K-fold CV $\rightarrow$ uses all data for training. Stacking generally performs better because no data wasted. Mixture of Experts: Uses a "gating network" to weigh the outputs of different "expert" models based on the input. $$ \hat{y} = \sum_i g_i(x) \cdot \hat{y}_i $$ === SUMMARY BOX: Ensemble Methods === Bagging reduces variance (averaging unstable models like deep trees). Random Forest = Bagging + feature subsampling $\rightarrow$ further reduces variance. RF: more trees never increase overfitting; more features per split increases correlation. Boosting reduces bias by fitting residuals sequentially. Too many boosting rounds or high learning rate $\rightarrow$ overfitting. Stacking trains meta-model on out-of-sample predictions $\rightarrow$ flexible & powerful. Bagging = parallel; Boosting = sequential; Stacking = layered. 6. Cheat-Sheet Trigger Words When you see... You think of... Overfitting $\rightarrow$ Too complex model, reduce depth, increase regularization, pruning, cross-validation. Underfitting $\rightarrow$ Too simple model, increase complexity, deeper models. Unstable predictions $\rightarrow$ High variance, consider bagging, random forest. High bias $\rightarrow$ Consider boosting, deeper models, gradient boosting. Correlated features $\rightarrow$ Regularization (Ridge/LASSO), PCA, Random Forest (random feature subset). Imbalanced data $\rightarrow$ Undersampling, oversampling (SMOTE), class weighting, ROC curve, F1-score. Non-linear relationships $\rightarrow$ Decision trees, polynomial regression, kNN. Interpretability desired $\rightarrow$ Simple linear/logistic regression, decision trees, simpler meta-models in ensembles. Probability estimation $\rightarrow$ Logistic regression, Bayesian models, Softmax. Categorical response $\rightarrow$ Logistic regression, decision trees, classification ensembles. Dealing with missing data $\rightarrow$ MCAR/MAR/MNAR, imputation methods (mean/median, model-based, indicator variables). 9. HIGH-YIELD EXAM TRIGGERS === HIGH-YIELD EXAM TRIGGERS === Identical X values with different labels $\rightarrow$ tree cannot reach 0 training error. ROC curve of Model A fully above Model B $\rightarrow$ A is strictly better. Threshold $\downarrow \rightarrow$ TPR $\uparrow$, FPR $\uparrow$ (more positives predicted). Extreme class imbalance $\rightarrow$ logistic regression predicts majority class. Ridge penalty (L2) $\rightarrow$ coefficients shrink, probabilities pulled toward 0.5. LASSO (L1) $\rightarrow$ feature selection (some $\beta_j = 0$). Bagging $\rightarrow$ reduces variance only (no effect on bias). Boosting $\rightarrow$ reduces bias (risk of higher variance, overfitting). Random Forest: increasing #trees NEVER increases overfitting. MICE / iterative imputation preserves relationships; mean imputation destroys them. MNAR $\rightarrow$ cannot be fixed using observed data alone. Stacking $\rightarrow$ uses OUT-OF-FOLD predictions to train meta-model (avoids leakage). Blending $\rightarrow$ meta-model trained on validation-set predictions (less training data). === CV Behavior Summary === Training error low, CV error high $\rightarrow$ Overfitting. Training error high, CV error high $\rightarrow$ Underfitting. CV error $\gg$ Test error $\rightarrow$ Data leakage. Use CV to tune: tree depth, $\lambda$, n_estimators, learning rate, min_samples_leaf. 8. Code Pattern Templates 8.1. Grid Search Template (Manual Hyperparameter Tuning) # Loop over hyperparameters (e.g., λ values) for λ in lambdas: model = Model(λ) # create model using parameter λ model.fit(X_train, y_train) # train on training set pred = model.predict(X_val) # predict on validation set score = metric(y_val, pred) # compute performance (lower/higher = better) # After loop completes: choose best λ based on score # select best-performing parameter High-level idea: This pattern = manual grid search. If you see a parameter inside a loop $\rightarrow$ they are tuning hyperparameters. 8.2. Cross-Validation Template (Train/Validate Loop) scores = [] for fold in K_folds: X_tr, y_tr = all_data except fold # training data X_val, y_val = fold # validation data model = Model() model.fit(X_tr, y_tr) # train on K-1 folds pred = model.predict(X_val) # validate on held-out fold scores.append(metric(y_val, pred)) # store performance cv_score = average(scores) # final CV estimate High-level idea: If you see a loop over folds $\rightarrow$ this is K-fold cross-validation. Key recognition: fit on K-1 folds, test on the remaining fold. 8.3. kNN Imputation Template (Predict Missing Values) # Split dataset into rows with and without missing entries known = rows where target is not missing missing = rows where target is missing # Fit kNN model to predict missing variable using other predictors knn.fit(known_predictors, known_target) # Predict the missing values pred_missing = knn.predict(missing_predictors) # Fill missing entries with predictions target[missing_rows] = pred_missing High-level idea: If the code: Splits data into missing vs non-missing; Fits model using other predictors; Assigns predictions into missing spots $\rightarrow$ It is model-based imputation (specifically kNN imputation). 8.4. Train/Test Split + Final Model Evaluation model = Model() model.fit(X_train, y_train) # train final model pred_test = model.predict(X_test) # evaluate on unseen data test_score = metric(y_test, pred_test) High-level idea: Trains once, evaluates once $\rightarrow$ final model performance, not tuning. 8.5. Parameter Sweep (General Pattern) results = [] for param in param_list: model = Model(param) model.fit(X, y) results.append(model.score(X, y)) High-level idea: Loop over parameters $\rightarrow$ they are analyzing effect of parameter (not necessarily CV). 8.6. Residual Fitting Template (Boosting Behavior) F0 = initial_model for m in range(M): residuals = y - Fm.predict(X) # compute current residuals tree_m = Tree() # weak learner tree_m.fit(X, residuals) # fit learner to residuals Fm+1 = Fm + η * tree_m # update model with learning rate η High-level idea: Model repeatedly fits residuals $\rightarrow$ this is boosting. 8.7. Bagging / Random Forest Pattern models = [] for b in range(B): sample = bootstrap_sample(data) # sample with replacement model = Tree() model.fit(sample.X, sample.y) models.append(model) # Prediction = average / majority vote y_pred = aggregate(model.predict(x) for model in models) High-level idea: Loop over bootstrap samples $\rightarrow$ bagging. Bootstrap + trees + feature subsampling inside $\rightarrow$ random forest. 8.8. Stacking (Meta-Model Pipeline) # Base model predictions on validation folds meta_features = [] for fold in K_folds: base_pred = base_model.predict(X_val) meta_features.append(base_pred) # Train meta-model on base predictions meta_model.fit(meta_features, y) # Final prediction: meta-model(base_model predictions on test) High-level idea: If you see predictions being used as new features, it is stacking.