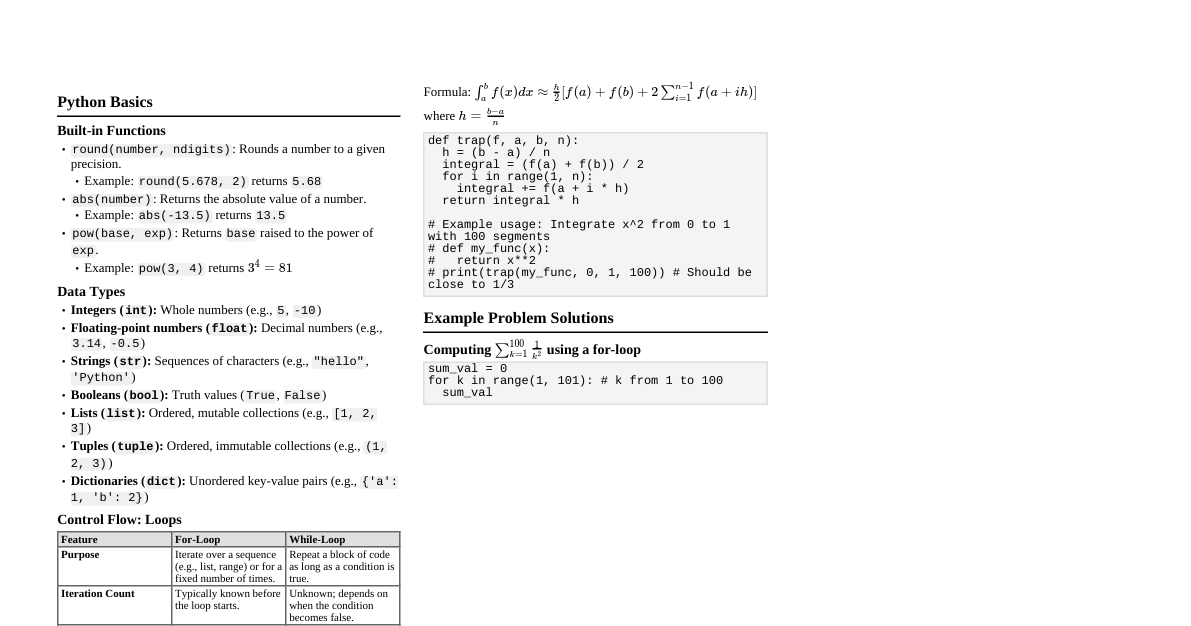

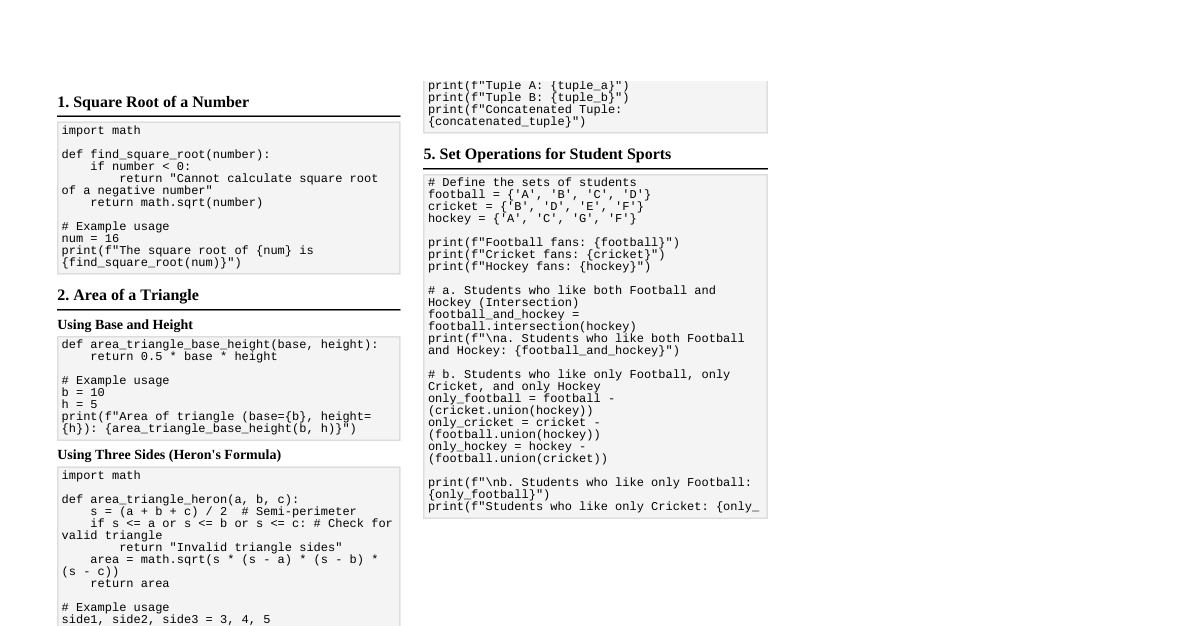

UNIT 1: Problem Solving & Python Basics 1. Problem Solving Process Define: Understand the problem, inputs, outputs, constraints. Plan: Devise a strategy (algorithm). Execute: Carry out the plan (code). Evaluate: Check if the solution works and is optimal. Example (Daily): Planning a trip. Define destination, budget. Plan route, accommodation. Execute travel. Evaluate experience. Similarity to Computer Problem Solving: Both require clear definition, systematic planning, execution, and verification. 2. Types of Problems Well-defined: Clear inputs, outputs, and solution steps (e.g., calculating area of a circle). Ill-defined: Ambiguous goals, unclear steps (e.g., "design a good user interface"). Simple: Few variables, straightforward solution (e.g., adding two numbers). Complex: Many variables, interconnected parts, requires decomposition (e.g., simulating weather patterns). Approach Difference: Well-defined/simple problems suit algorithmic solutions. Ill-defined/complex problems require iterative, exploratory, and often creative approaches. 3. Problem Solving with Computers Systematic Approach: Problem Definition: Clearly state what needs to be solved. Analysis: Break down the problem, identify data, processes, constraints. Design: Create an algorithm, flowchart, or pseudocode. Implementation: Write code based on the design. Testing & Debugging: Verify correctness. Maintenance: Update and improve. Importance of Definition, Analysis, Design: These steps ensure the correct problem is solved efficiently before coding begins, reducing errors and rework. 4. Difficulties in Problem Solving Misunderstanding the Problem: Incorrect interpretation of requirements. Real-life: Buying wrong ingredients for a recipe. Computing: Coding for the wrong user story. Overcome: Ask clarifying questions, rephrase, draw diagrams. Lack of Information: Missing data or context. Real-life: Can't plan a route without a map. Computing: Missing API documentation. Overcome: Research, consult experts, make assumptions (and validate). Poor Planning/Design: Inefficient or incorrect strategy. Real-life: Building a house without blueprints. Computing: Writing spaghetti code. Overcome: Use structured design tools (flowcharts, pseudocode), peer review. Debugging Issues: Difficulty finding and fixing errors. Real-life: Car not starting, but you don't know why. Computing: Logic errors in code. Overcome: Systematic testing, logging, divide and conquer. 5. Aspects of Problem Solving Understanding: Grasping the problem's core, inputs, outputs, constraints. Planning: Devising a step-by-step method to solve it. Executing: Carrying out the plan (e.g., writing the code). Evaluating: Checking the solution for correctness, efficiency, and robustness. Example (Calculating Average): Understand: Need to sum numbers and divide by count. Plan: Get numbers, initialize sum=0, count=0. Loop: add number to sum, increment count. Divide sum by count. Execute: Write Python code for this logic. Evaluate: Test with known values (e.g., average of 1,2,3 is 2). 6. Top-Down Design Approach Breaks down a complex problem into smaller, more manageable sub-problems. Each sub-problem is then further broken down until it becomes trivial to solve. Helps in: Modularity, easier debugging, reusability. Example: Designing a student grading system Main Problem: Student Grading System $\downarrow$ Sub-problems: Input Student Data, Calculate Grades, Generate Reports $\downarrow$ Further Sub-problems (e.g., under Calculate Grades): Calculate Total Marks, Assign Letter Grade 7. Problem Solving Strategies Trial and Error: Trying different solutions until one works. (e.g., guessing a password, simple debugging). Divide and Conquer: Breaking a problem into smaller, independent sub-problems (e.g., merge sort, top-down design). Working Backward: Starting from the desired outcome and figuring out the steps to get there (e.g., solving a maze from the end). Using Analogies: Solving a new problem by relating it to a previously solved similar problem (e.g., using a known sorting algorithm for a new data type). Algorithmic Approach: Following a predefined set of steps (algorithm) to guarantee a solution (e.g., baking a cake, using a search algorithm). 8. Program Design Tools Algorithms: Step-by-step procedure to solve a problem. Advantage: Language-independent, clear logic. Limitation: Can be abstract, hard to visualize flow. Flowcharts: Graphical representation of an algorithm using standard symbols. Advantage: Visual, easy to understand flow. Limitation: Cumbersome for complex problems, hard to modify. Pseudocode: Informal high-level description of an algorithm, resembling programming language but without strict syntax. Advantage: Easy to write, bridge between algorithm and code. Limitation: No standard syntax, can be ambiguous. 9. Algorithm Implementation Steps Understand the Problem: Define inputs, outputs. Design Algorithm: Create steps (pseudocode/flowchart). Choose Language: Select appropriate programming language. Write Code: Translate algorithm into code. Test: Run with various inputs to check correctness. Debug: Fix errors found during testing. Example: Finding largest of three numbers # Algorithm: # 1. Get three numbers: num1, num2, num3 # 2. Assume largest = num1 # 3. If num2 > largest, then largest = num2 # 4. If num3 > largest, then largest = num3 # 5. Print largest # Python Implementation: num1 = int(input("Enter first number: ")) num2 = int(input("Enter second number: ")) num3 = int(input("Enter third number: ")) largest = num1 if num2 > largest: largest = num2 if num3 > largest: largest = num3 print("The largest number is:", largest) 10. Case Study: Student Grade Calculation Problem: Calculate student grade based on marks in 5 subjects. Algorithm: START READ marks for 5 subjects: $S_1, S_2, S_3, S_4, S_5$ CALCULATE Total Marks: $Total = S_1 + S_2 + S_3 + S_4 + S_5$ CALCULATE Percentage: $Percentage = (Total / 500) * 100$ IF Percentage >= 90 THEN Grade = 'A' ELSE IF Percentage >= 80 THEN Grade = 'B' ELSE IF Percentage >= 70 THEN Grade = 'C' ELSE IF Percentage >= 60 THEN Grade = 'D' ELSE Grade = 'F' PRINT Grade END Pseudocode: FUNCTION CalculateGrade(): INPUT S1, S2, S3, S4, S5 Total = S1 + S2 + S3 + S4 + S5 Percentage = (Total / 500) * 100 IF Percentage >= 90 THEN Grade = 'A' ELSE IF Percentage >= 80 THEN Grade = 'B' ELSE IF Percentage >= 70 THEN Grade = 'C' ELSE IF Percentage >= 60 THEN Grade = 'D' ELSE Grade = 'F' END IF PRINT Grade END FUNCTION Flowchart (Conceptual): Start Read S1..S5 Total = Sum(S1..S5) Percentage = (Total/500)*100 Percentage >= 90? Yes No Grade = 'A' Percentage >= 80? Yes No Grade = 'B' Percentage >= 70? Yes No Grade = 'C' Grade = 'F' Print Grade End 11. Features of Python Easy to Learn & Use: Simple syntax, readable code. Interpreted Language: Code executed line by line, easier debugging. High-Level Language: Abstracts away complex memory management. Dynamically Typed: Variable types checked at runtime. Object-Oriented: Supports classes and objects. Extensive Standard Library: Rich set of modules for various tasks. Cross-Platform: Runs on Windows, macOS, Linux. Open Source: Free to use and distribute. Comparison (vs. C++): Feature Python C++ Syntax Simple, readable Complex, verbose Typing Dynamic Static Memory Mgt. Automatic (Garbage Collection) Manual Speed Slower (interpreted) Faster (compiled) Use Case Web dev, AI, scripting System programming, games 12. History and Future of Python Origin: Created by Guido van Rossum, first released in 1991. Versions: Python 2.x (legacy), Python 3.x (current standard). Major Developments: Growing standard library, NumPy/Pandas for data science, Django/Flask for web, TensorFlow/PyTorch for AI. Current Applications: Web Development (Django, Flask), Data Science (NumPy, Pandas, Scikit-learn), AI/Machine Learning, Automation, Scripting, Scientific Computing. Future Scope: Continued growth in AI, IoT, web services, and education due to its versatility and ease of use. 13. Writing and Executing Python Program Example Program: # hello.py name = input("What's your name? ") print("Hello,", name + "!") IDLE (Integrated Development and Learning Environment): Open IDLE. Go to File -> New File (creates a new editor window). Type the code and save as hello.py . Go to Run -> Run Module (or press F5). Output appears in the IDLE Shell. Command Line: Save the code as hello.py in a directory (e.g., C:\Python_Projects ). Open Command Prompt/Terminal. Navigate to the directory: cd C:\Python_Projects . Execute: python hello.py . The program will run and prompt for input. Jupyter Notebook: Start Jupyter Notebook ( jupyter notebook in terminal). Create a new Python 3 notebook. Type the code into a cell. Run the cell (Shift + Enter). Output appears directly below the cell. 14. Literal Constants, Variables, and Identifiers Literal Constants: Fixed data values, cannot be changed. Examples: 100 (integer), 3.14 (float), "Hello" (string), True (boolean). Variables: Named storage locations that hold values. Their values can change. Example: age = 30 ( age is the variable, 30 is the literal constant assigned to it). age = age + 1 (value of age changes to 31 ). Identifiers: Names given to variables, functions, classes, modules, etc. Examples: my_variable , calculate_sum , MyClass . Rules for Naming Identifiers: Can contain letters (a-z, A-Z), digits (0-9), and underscore (_). Cannot start with a digit. Case-sensitive ( myVar is different from myvar ). Cannot be a Python reserved word (keyword). Conventionally, use lowercase for variables/functions, PascalCase for classes. 15. Data Types in Python Numeric: int (integers): 10 , -5 float (floating-point numbers): 3.14 , -0.5 complex (complex numbers): 1 + 2j String: Immutable sequence of characters. str : "hello" , 'Python' Boolean: Logical values. bool : True , False Sequence Types: Ordered collections. list : Mutable, ordered collection. [1, 2, 'a'] tuple : Immutable, ordered collection. (1, 2, 'a') range : Immutable sequence of numbers. range(0, 5) Set: Unordered collection of unique items. set : Mutable. {1, 2, 3} frozenset : Immutable version of set. Dictionary: Unordered collection of key-value pairs. dict : Mutable. {'name': 'Alice', 'age': 30} 16. Input Operation and Comments input() function: Reads input from the user as a string. name = input("Enter your name: ") # user types "Alice" age = int(input("Enter your age: ")) # user types "25", converted to int print(f"Hello {name}, you are {age} years old.") Comments: Explanatory notes in code, ignored by interpreter. Single-line: Starts with # . # This is a single-line comment x = 10 # This comment explains x Multi-line: Enclosed in triple quotes ( '''...''' or """...""" ). Often used for docstrings. ''' This is a multi-line comment. It can span several lines. ''' def my_function(): """This is a docstring for the function.""" pass Importance of Comments: Improve code readability, explain complex logic, aid in maintenance, and help other developers understand the code. 17. Reserved Words and Indentation Reserved Words (Keywords): Words with special meaning in Python, cannot be used as identifiers. Examples: False , None , True , and , as , assert , async , await , break , class , continue , def , del , elif , else , except , finally , for , from , global , if , import , in , is , lambda , nonlocal , not , or , pass , raise , return , try , while , with , yield . Indentation: Python uses whitespace (spaces or tabs, conventionally 4 spaces) to define code blocks (e.g., inside if statements, loops, functions). Importance: It's crucial for syntax; incorrect indentation causes IndentationError . # Correct Indentation if True: print("This is inside the if block.") x = 10 print("This is outside the if block.") # Incorrect Indentation (will cause error) # if True: # print("Error: expected an indented block") 18. Operators and Expressions Operators: Symbols that perform operations on values and variables. Expressions: Combinations of values, variables, and operators that evaluate to a single value. Categories: Arithmetic: + , - , * , / (true division), // (floor division), % (modulo), ** (exponentiation). Example: result = 10 + 5 * 2 (evaluates to 20 ) Relational (Comparison): == , != , > , , >= , . Return Boolean. Example: is_equal = (5 == 5) ( True ) Logical: and , or , not . Combine Boolean expressions. Example: condition = (True and False) ( False ) Assignment: = , += , -= , *= , /= , etc. Assign values. Example: x = 10 ; x += 5 ( x becomes 15 ) Bitwise: & (AND), | (OR), ^ (XOR), ~ (NOT), (left shift), >> (right shift). Operate on bits. Example: 5 & 3 ( 1 , binary 101 & 011 = 001 ) Membership: in , not in . Check if a value is present in a sequence. Example: 'a' in 'apple' ( True ) Identity: is , is not . Check if two variables refer to the same object in memory. Example: a = [1]; b = [1]; a is b ( False , different objects with same value) 19. Tuples, Lists, and Dictionaries Feature List Tuple Dictionary Definition [item1, item2] (item1, item2) {key1: val1, key2: val2} Mutability Mutable (can change elements) Immutable (cannot change elements) Mutable (can add/remove key-value pairs, change values) Ordering Ordered (maintains insertion order) Ordered (maintains insertion order) Ordered (Python 3.7+ guarantees insertion order) Indexing By integer index ( list[0] ) By integer index ( tuple[0] ) By key ( dict['key'] ) Use Cases Collections of similar items, dynamic data. Fixed collections, function return multiple values, dictionary keys. Key-value mappings, fast lookups. Example my_list = [1, 'a', 3.0] my_tuple = (1, 'a', 3.0) my_dict = {'x': 10, 'y': 20} 20. Expressions in Python Definition: A piece of code that produces a value. Evaluation: Python evaluates expressions based on operator precedence and associativity. Arithmetic Expressions: x = 10 y = 3 result = x + y * 2 # y * 2 evaluates first (6), then x + 6 (16) print(result) # Output: 16 String Expressions: greeting = "Hello" + " " + "World!" # Concatenation print(greeting) # Output: Hello World! repeated = "abc" * 3 # Multiplication (repeats string) print(repeated) # Output: abcabcabc Logical Expressions: age = 25 is_adult = (age > 18) and (age UNIT 2: Decision Control Statements & Loops Q1. Decision Control Statements What they are: Statements that allow a program to execute different blocks of code based on whether certain conditions are met. Why used: To introduce logic and make programs respond dynamically to inputs or changing conditions. They control the "flow of execution." How they help control flow: Instead of executing instructions sequentially, decision statements allow the program to "branch" to different parts of the code. Examples: # if statement age = 20 if age >= 18: print("You are an adult.") # if-else statement temperature = 25 if temperature > 30: print("It's hot!") else: print("It's not too hot.") # if-elif-else statement score = 75 if score >= 90: print("Grade A") elif score >= 80: print("Grade B") elif score >= 70: print("Grade C") else: print("Grade D or F") Q2. Selection (Conditional Branching) Statements Definition: Statements that allow the program to choose which block of code to execute next based on a condition. Single Branching ( if ): Executes a block only if the condition is true. x = 10 if x > 5: print("x is greater than 5") Double Branching ( if-else ): Executes one block if the condition is true, another if false. y = 3 if y % 2 == 0: print("y is even") else: print("y is odd") Multiple Branching ( if-elif-else ): Checks multiple conditions sequentially, executing the block for the first true condition. day = "Tuesday" if day == "Monday": print("Start of week") elif day == "Friday": print("End of week") else: print("Mid-week") Q3. if-elif-else Statement Syntax & Structure: if condition1: # code block 1 elif condition2: # code block 2 elif condition3: # code block 3 else: # code block 4 (optional, executes if no conditions above are true) Importance: Allows for handling multiple distinct scenarios or choices in a clean and efficient way, preventing long chains of nested if statements. It selects one option among many. Program to classify student grades: percentage = float(input("Enter student's percentage: ")) if percentage >= 90: grade = 'A' elif percentage >= 80: grade = 'B' elif percentage >= 70: grade = 'C' elif percentage >= 60: grade = 'D' else: grade = 'F' print(f"The student's grade is: {grade}") Q4. Nested if Statements Definition: An if or if-else statement placed inside another if or else block. Used for complex conditions where a condition depends on another condition. Syntax: if condition1: # code block for condition1 if condition2: # code block for condition2 (nested) else: # code block for not condition2 (nested) else: # code block for not condition1 Python program: Check number's sign and parity num = int(input("Enter an integer: ")) if num >= 0: if num == 0: print("The number is Zero.") else: # num is positive print("The number is Positive.") if num % 2 == 0: print("It is an Even number.") else: print("It is an Odd number.") else: # num is negative print("The number is Negative.") if num % 2 == 0: print("It is an Even number.") else: print("It is an Odd number.") Step-by-step explanation (e.g., num = 4): num = 4 . First if num >= 0 ( 4 >= 0 ) is True. Enter the outer if block. Inner if num == 0 ( 4 == 0 ) is False. Enter the inner else block. Print "The number is Positive.". Next inner if num % 2 == 0 ( 4 % 2 == 0 ) is True. Print "It is an Even number.". Exit all blocks. Q5. Basic Loop Structures in Python Concept of Iteration: Repeating a block of code multiple times. Why loops are used: To avoid code duplication, process collections of data, and perform tasks repeatedly until a condition is met. while loop: Repeats a block of code as long as a condition is true. Syntax: while condition: # code block to repeat # (must eventually make condition false to avoid infinite loop) Working: Checks condition, if True, executes block, then re-checks condition. Example: count = 0 while count for loop: Iterates over a sequence (list, tuple, string, range) or other iterable objects. Syntax: for item in iterable: # code block to execute for each item Working: Assigns each item from the iterable to the loop variable and executes the block. Example: fruits = ["apple", "banana", "cherry"] for fruit in fruits: print(fruit) # Output: # apple # banana # cherry for i in range(3): # range(3) generates 0, 1, 2 print("Iteration:", i) # Output: # Iteration: 0 # Iteration: 1 # Iteration: 2 Q6. Compare for loop and while loop When to use: for loop: When you know the number of iterations beforehand (e.g., iterating through a list, a fixed range of numbers). Best for definite iteration. while loop: When the number of iterations is unknown and depends on a condition (e.g., reading user input until a specific value, waiting for a flag to change). Best for indefinite iteration. Examples: Printing a range of numbers using for : print("Using for loop:") for i in range(1, 6): # Numbers 1 to 5 print(i) Printing the same using while : print("Using while loop:") j = 1 while j Feature for loop while loop Control Iterates over a sequence/iterable. Repeats as long as a condition is true. Iterations Definite (known beforehand). Indefinite (depends on condition). Initialization Implicit (done by iterable). Explicit (variable must be initialized before loop). Termination Automatically terminates after iterating through all items. Requires explicit update of condition variable to avoid infinite loop. Use Cases Iterating lists, strings, ranges, files. Repeating until user input, processing queues, game loops. Q7. Nested Loops Definition: A loop inside another loop. The inner loop completes all its iterations for each single iteration of the outer loop. How inner and outer loops work: for i in range(3): # Outer loop (i = 0, 1, 2) for j in range(2): # Inner loop (j = 0, 1) print(f"i: {i}, j: {j}") # Output: # i: 0, j: 0 # i: 0, j: 1 # i: 1, j: 0 # i: 1, j: 1 # i: 2, j: 0 # i: 2, j: 1 Program 1: Multiplication table from 1 to 5 for i in range(1, 6): # Outer loop for multiplicand (1 to 5) print(f"--- Table of {i} ---") for j in range(1, 11): # Inner loop for multiplier (1 to 10) print(f"{i} x {j} = {i * j}") Program 2: Right-angled triangle pattern rows = 5 for i in range(1, rows + 1): # Outer loop for rows for j in range(i): # Inner loop for columns (prints 'i' stars) print("*", end="") print() # Newline after each row # Output: # * # ** # *** # **** # ***** Dry-run explanation for triangle pattern (rows = 3): Outer loop: i = 1 Inner loop: j in range(1) (only j=0 ) print("*", end="") -> prints * print() -> moves to next line Outer loop: i = 2 Inner loop: j in range(2) ( j=0, 1 ) print("*", end="") -> prints * print("*", end="") -> prints * print() -> moves to next line Outer loop: i = 3 Inner loop: j in range(3) ( j=0, 1, 2 ) print("*", end="") -> prints * print("*", end="") -> prints * print("*", end="") -> prints * print() -> moves to next line Q8. Loop Control Statements break : Purpose: Immediately terminates the current loop ( for or while ) and transfers control to the statement immediately following the loop. When used: To exit a loop early when a specific condition is met, typically when a desired item is found or an error occurs. Program: print("--- break example ---") for i in range(1, 10): if i == 5: print("Found 5, breaking loop.") break print(i) # Output: 1 2 3 4 Found 5, breaking loop. continue : Purpose: Skips the rest of the current iteration of the loop and proceeds to the next iteration. When used: To bypass specific elements or conditions within a loop without terminating the entire loop. Program: print("--- continue example ---") for i in range(1, 6): if i == 3: print("Skipping 3.") continue print(i) # Output: 1 2 Skipping 3. 4 5 pass : Purpose: A null operation; nothing happens when it executes. It's a placeholder statement. When used: When Python syntax requires a statement but you don't want any action to be performed (e.g., in an empty function, class, or loop body). Program: print("--- pass example ---") for i in range(3): if i == 1: pass # Do nothing when i is 1 else: print(f"Processing item {i}") # Output: # Processing item 0 # Processing item 2 def empty_function(): pass # Function definition requiring a block UNIT 3: Functions and Modules Q1. User-Defined Functions in Python Definition: Reusable blocks of code designed to perform a specific task. They promote modularity and code reuse. Syntax of Function Definition: def function_name(parameter1, parameter2, ...): """Docstring: explains what the function does.""" # Function body - statements that perform the task # ... return result # Optional: returns a value Syntax of Function Calling: function_name(argument1, argument2, ...) Python program: Sum, average, max of three numbers def calculate_sum(a, b, c): """Calculates the sum of three numbers.""" return a + b def calculate_average(a, b, c): """Calculates the average of three numbers.""" total = calculate_sum(a, b, c) # Reusing sum function return total / 3 def find_maximum(a, b, c): """Finds the maximum of three numbers.""" maximum = a if b > maximum: maximum = b if c > maximum: maximum = c return maximum # Main part of the program num1 = 10 num2 = 20 num3 = 15 # Function calls total_sum = calculate_sum(num1, num2, num3) avg = calculate_average(num1, num2, num3) max_num = find_maximum(num1, num2, num3) print(f"Numbers: {num1}, {num2}, {num3}") print(f"Sum: {total_sum}") print(f"Average: {avg}") print(f"Maximum: {max_num}") Q2. Returning Values from a Function The return statement is used to send a value (or values) back from a function to the caller. 1. Returning a single value: def square(number): return number * number result = square(5) print(result) # Output: 25 Flow of execution: When square(5) is called, control jumps to the function. number * number ( 5 * 5 = 25 ) is computed. The return 25 statement sends 25 back to where the function was called. result then gets assigned 25 . 2. Returning multiple values: Python functions can implicitly return multiple values as a tuple. def get_min_max(numbers): if not numbers: return None, None # Return two None values return min(numbers), max(numbers) # Returns a tuple (min_val, max_val) my_list = [3, 1, 4, 1, 5, 9, 2] minimum, maximum = get_min_max(my_list) # Tuple unpacking print(f"Min: {minimum}, Max: {maximum}") # Output: Min: 1, Max: 9 empty_list = [] min_val, max_val = get_min_max(empty_list) print(f"Min: {min_val}, Max: {max_val}") # Output: Min: None, Max: None Flow of execution: get_min_max(my_list) is called. Inside, min(numbers) and max(numbers) are computed. The return statement bundles these two values into a tuple (e.g., (1, 9) ) and sends it back. This tuple is then unpacked into minimum and maximum variables. Q3. Scope and Lifetime of Variables Scope: The region of a program where a variable is accessible. Lifetime: The period during which a variable exists in memory. Local Variables: Scope: Defined inside a function. Accessible only within that function. Lifetime: Created when the function is called, destroyed when the function finishes execution. Example: def my_func(): local_var = 10 # local_var is local to my_func print(local_var) my_func() # Output: 10 # print(local_var) # This would cause a NameError Global Variables: Scope: Defined outside any function. Accessible from anywhere in the module, including inside functions (for reading). Lifetime: Created when the program starts, destroyed when the program ends. Example: global_var = 20 # global_var is global def another_func(): print(global_var) # Can read global_var another_func() # Output: 20 print(global_var) # Output: 20 Nonlocal Variables (in nested functions): Used in nested functions to refer to variables in the nearest enclosing (non-global) scope. Allows modifying a variable from an outer function's scope, but not the global scope. Example: def outer_func(): x = 10 # This is 'x' in the outer_func's scope def inner_func(): nonlocal x # Declares x refers to x in outer_func's scope x = 20 # Modifies outer_func's x print("Inner x:", x) inner_func() print("Outer x:", x) outer_func() # Output: # Inner x: 20 # Outer x: 20 Q4. Global Variable Modification with global keyword What is a global variable? A variable defined outside of any function, accessible throughout the entire program. How to create/modify inside a function: To modify a global variable from within a function, you must explicitly declare it using the global keyword. Without global , assigning to a variable with the same name inside a function creates a new local variable. Python program: global_counter = 0 # Global variable def increment_global_counter(): global global_counter # Declare intent to modify the global variable global_counter += 1 print(f"Inside function: global_counter = {global_counter}") def create_local_counter(): # This creates a new local_counter, doesn't affect global_counter global_counter = 100 print(f"Inside function (local): global_counter = {global_counter}") print(f"Before function call: global_counter = {global_counter}") # Output: 0 increment_global_counter() # Output: Inside function: global_counter = 1 print(f"After first call: global_counter = {global_counter}") # Output: 1 increment_global_counter() # Output: Inside function: global_counter = 2 print(f"After second call: global_counter = {global_counter}") # Output: 2 create_local_counter() # Output: Inside function (local): global_counter = 100 print(f"After create_local_counter: global_counter = {global_counter}") # Output: 2 (global_counter unchanged) Explanation: In increment_global_counter() , global global_counter tells Python to use the globally defined global_counter . In create_local_counter() , without global , global_counter = 100 creates a new local variable, leaving the global one untouched. Q5. Passing Collections to a Function Collections (lists, tuples, dictionaries) are passed by object reference in Python. Changes made to mutable collections (lists, dictionaries) inside a function will affect the original collection outside the function. (a) Print all elements of a list: def print_list_elements(my_list_param): """Prints each element of a list.""" print("Elements in the list:") for item in my_list_param: print(item) my_list_param.append("new_item") # Modifies the original list data_list = [10, 20, 30] print("Original list:", data_list) # Output: Original list: [10, 20, 30] print_list_elements(data_list) # Output: # Elements in the list: # 10 # 20 # 30 print("List after function call:", data_list) # Output: List after function call: [10, 20, 30, 'new_item'] (b) Display all keys and values of a dictionary: def display_dict_contents(my_dict_param): """Displays keys and values of a dictionary.""" print("Dictionary contents:") for key, value in my_dict_param.items(): print(f"Key: {key}, Value: {value}") my_dict_param['city'] = 'New York' # Modifies the original dictionary user_profile = {'name': 'Alice', 'age': 30} print("Original dictionary:", user_profile) # Output: Original dictionary: {'name': 'Alice', 'age': 30} display_dict_contents(user_profile) # Output: # Dictionary contents: # Key: name, Value: Alice # Key: age, Value: 30 print("Dictionary after function call:", user_profile) # Output: Dictionary after function call: {'name': 'Alice', 'age': 30, 'city': 'New York'} Q6. Variable-Length Arguments, Default & Optional Parameters Variable-Length Arguments: Allow a function to accept an arbitrary number of arguments. *args (Non-keyword arguments): Collects an arbitrary number of positional arguments into a tuple. def sum_all_numbers(*numbers): """Sums all numbers passed as arguments.""" total = 0 for num in numbers: total += num return total print(sum_all_numbers(1, 2, 3)) # Output: 6 print(sum_all_numbers(10, 20, 30, 40)) # Output: 100 print(sum_all_numbers()) # Output: 0 **kwargs (Keyword arguments): Collects an arbitrary number of keyword arguments into a dictionary. def display_user_info(**info): """Displays user information from keyword arguments.""" for key, value in info.items(): print(f"{key.replace('_', ' ').title()}: {value}") display_user_info(name="Bob", age=25, city="London") # Output: # Name: Bob # Age: 25 # City: London display_user_info(product="Laptop", price=1200) # Output: # Product: Laptop # Price: 1200 Default Parameters: Parameters that have a default value if no argument is provided during the function call. def greet(name="Guest", message="Hello"): """Greets a person with an optional message.""" print(f"{message}, {name}!") greet("Alice") # Output: Hello, Alice! greet("Bob", "Hi") # Output: Hi, Bob! greet(message="Hola") # Output: Hola, Guest! greet() # Output: Hello, Guest! Optional Parameters: Parameters with default values are considered optional. They must be defined after all required parameters. Q7. Nested Functions & Advantages/Disadvantages of Recursion Nested Functions: Functions defined inside other functions. They can access variables of the enclosing (outer) function's scope. They help in encapsulating helper functions and creating closures. def outer_function(msg): text = msg # 'text' is in outer_function's scope def inner_function(): # inner_function can access 'text' from outer_function's scope print(text) return inner_function # Returns the inner function object my_closure = outer_function("Hello from outer!") my_closure() # Output: Hello from outer! Nonlocal variables in nested functions: (See Q3 for example) The nonlocal keyword allows a nested function to modify a variable in its immediately enclosing scope (not global). Advantages of Recursive Functions: Elegance & Readability: For problems naturally defined recursively (e.g., tree traversals, factorial), recursive solutions can be more concise and easier to understand. Code Reduction: Often leads to less code than an iterative counterpart. Solving Complex Problems: Some problems are inherently recursive (e.g., Tower of Hanoi). Disadvantages of Recursive Functions: Memory Overhead: Each recursive call consumes stack space (for storing function state), potentially leading to `StackOverflowError` for deep recursion. Performance: Can be slower than iterative solutions due to function call overhead. Debugging: Tracing execution flow can be harder. Complexity: Harder to reason about for beginners. Q8. Recursive Functions Definition: A function that calls itself, either directly or indirectly, to solve a problem. It works by breaking down a problem into smaller, similar sub-problems until a base case is reached. Key components: Base Case: A condition that stops the recursion. Without it, the function would call itself infinitely. Recursive Step: The part where the function calls itself with a modified (smaller) input, moving towards the base case. 1. Factorial of a number: $n! = n \times (n-1)!$, base case $0! = 1$. def factorial(n): """Calculates factorial recursively.""" if n == 0: # Base case return 1 else: # Recursive step return n * factorial(n - 1) print(factorial(5)) # Output: 120 (5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1) print(factorial(0)) # Output: 1 2. Generate Fibonacci series: $F(n) = F(n-1) + F(n-2)$, base cases $F(0)=0, F(1)=1$. def fibonacci(n): """Generates the nth Fibonacci number recursively.""" if n Advantages & Disadvantages: (See Q7) Q9. Functions as Arguments & Higher-Order Functions Functions as Arguments: In Python, functions are first-class objects, meaning they can be passed as arguments to other functions, returned from functions, and assigned to variables. def apply_operation(func, x, y): """Applies a given function to two arguments.""" return func(x, y) def add(a, b): return a + b def multiply(a, b): return a * b result_add = apply_operation(add, 5, 3) result_mul = apply_operation(multiply, 5, 3) print(f"Addition result: {result_add}") # Output: Addition result: 8 print(f"Multiplication result: {result_mul}") # Output: Multiplication result: 15 map() function: Applies a given function to all items in an iterable (e.g., list, tuple) and returns a map object (an iterator). numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4] squared_numbers = list(map(lambda x: x*x, numbers)) print(squared_numbers) # Output: [1, 4, 9, 16] filter() function: Constructs an iterator from elements of an iterable for which a function returns true. ages = [5, 12, 17, 18, 24, 32] adult_ages = list(filter(lambda age: age >= 18, ages)) print(adult_ages) # Output: [18, 24, 32] lambda functions (Anonymous Functions): Small, single-expression functions, not bound to a name. Used for short, throwaway functions. # Regular function def add_one(x): return x + 1 # Equivalent lambda function add_one_lambda = lambda x: x + 1 print(add_one(10)) # Output: 11 print(add_one_lambda(10)) # Output: 11 They are commonly used with map() , filter() , and sorted() . Q10. Modules in Python Definition: A file containing Python definitions and statements. The filename is the module name with the .py extension. Why used: Code Organization: Group related code into separate files. Reusability: Use functions/classes defined in one module in multiple other programs. Namespace Management: Avoids name collisions by providing a separate namespace for each module. Ways of Importing Modules: import module_name : Imports the entire module. Access members using module_name.member . import math print(math.pi) print(math.sqrt(16)) from module_name import member1, member2 : Imports specific members directly into the current namespace. from math import pi, sqrt print(pi) print(sqrt(25)) # print(math.floor(3.7)) # This would cause a NameError as 'math' itself is not imported from module_name import * : Imports all public members into the current namespace. (Generally discouraged as it can lead to name conflicts). import module_name as alias_name : Imports the module and gives it a shorter alias. import numpy as np # Common convention arr = np.array([1, 2, 3]) Creating and Using User-Defined Modules: 1. Create a file (e.g., my_module.py ): # my_module.py def greeting(name): return f"Hello, {name}!" def add_numbers(a, b): return a + b my_variable = "This is a custom variable." 2. Use it in another file (e.g., main.py in the same directory): # main.py import my_module print(my_module.greeting("Alice")) print(my_module.add_numbers(10, 5)) print(my_module.my_variable) from my_module import greeting as greet_user print(greet_user("Bob")) Advantages in Large Programs: Maintainability: Easier to manage and debug smaller, focused modules. Collaboration: Multiple developers can work on different modules simultaneously. Reduced Complexity: Breaks down a large problem into smaller, manageable parts. Namespace Isolation: Prevents accidental overwriting of variable/function names. Q11. Packages in Python Definition: A way of organizing related modules into a directory hierarchy. A package is essentially a directory containing a special file named __init__.py (which can be empty). How it differs from a module: A module is a single .py file. A package is a directory containing multiple modules and sub-packages. It's a way to structure a namespace using "dotted module names" (e.g., package.module ). Structure of a Package: my_package/ __init__.py module_a.py module_b.py sub_package/ __init__.py sub_module_c.py Role of __init__.py : Marks a directory as a Python package. Can contain initialization code for the package (e.g., defining __all__ , setting up package-level variables). Executed automatically when the package (or a module within it) is imported. Example showing access to modules inside a package: # my_package/module_a.py def func_a(): return "Function A from module_a" # my_package/sub_package/sub_module_c.py def func_c(): return "Function C from sub_module_c" # In a separate script: # import my_package.module_a # print(my_package.module_a.func_a()) # from my_package.module_b import * # Assuming module_b exists # from my_package.sub_package import sub_module_c # print(sub_module_c.func_c()) # Or more commonly: from my_package.module_a import func_a from my_package.sub_package.sub_module_c import func_c print(func_a()) # Output: Function A from module_a print(func_c()) # Output: Function C from sub_module_c Q12. Python Standard Library Modules What it is: A vast collection of modules that come pre-installed with Python. It provides solutions for common programming tasks, from file I/O to network communication, math, and more. Why important: "Batteries Included": Reduces the need for external libraries for many tasks. Reliability: Modules are well-tested and maintained. Productivity: Speeds up development by providing ready-to-use functionalities. Four Standard Library Modules: 1. math : Provides mathematical functions. import math print(f"Pi: {math.pi}") print(f"Square root of 64: {math.sqrt(64)}") print(f"Ceiling of 4.3: {math.ceil(4.3)}") # Output: 5 print(f"Floor of 4.7: {math.floor(4.7)}") # Output: 4 2. random : Generates pseudo-random numbers. import random print(f"Random float (0.0 to 1.0): {random.random()}") print(f"Random integer (1 to 10): {random.randint(1, 10)}") my_list = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry'] print(f"Random choice from list: {random.choice(my_list)}") 3. datetime : Classes for working with dates and times. import datetime # Current date and time now = datetime.datetime.now() print(f"Current date and time: {now}") # Specific date dt = datetime.date(2023, 10, 26) print(f"Specific date: {dt}") # Time difference duration = datetime.timedelta(days=5, hours=3) future_date = now + duration print(f"Date after 5 days 3 hours: {future_date}") 4. os : Provides a way of using operating system dependent functionality (e.g., file system paths, environment variables). import os print(f"Current working directory: {os.getcwd()}") # os.mkdir("test_dir") # Creates a new directory # print(os.listdir(".")) # Lists contents of current directory # os.rmdir("test_dir") # Removes the directory print(f"Environment variable PATH: {os.environ.get('PATH')[:50]}...") UNIT 4: Strings Q1. What are strings in Python? Definition: Sequences of Unicode characters. They are immutable, meaning once created, their contents cannot be changed. Examples: str1 = "Hello, World!" str2 = 'Python' str3 = """This is a multi-line string.""" Storage and Access (Indexing): Strings are stored as an ordered sequence of characters. Each character has an index, starting from 0 for the first character. Negative indices count from the end of the string (-1 for the last character). my_string = "Python" print(my_string[0]) # Output: P (first character) print(my_string[5]) # Output: n (last character) print(my_string[-1]) # Output: n (last character) print(my_string[-6]) # Output: P (first character) Q2. String Concatenation Definition: The process of joining two or more strings together to form a new string. Using + operator: first_name = "John" last_name = "Doe" full_name = first_name + " " + last_name print(full_name) # Output: John Doe greeting = "Hello" message = greeting + ", how are you?" print(message) # Output: Hello, how are you? Concatenation ( + ) vs. Appending ( append() for lists): Feature String Concatenation ( + ) List Appending ( .append() ) Data Type Strings only Lists only Mutability Creates a NEW string (strings are immutable). Modifies the ORIGINAL list (lists are mutable). Operation Joins two strings to make a longer one. Adds a single element to the end of a list. Example s = "a" + "b" ( s is "ab" ) l = [1]; l.append(2) ( l becomes [1, 2] ) Q3. String Multiplication Definition: Repeating a string a specified number of times using the * operator. Examples: pattern = "-" * 10 print(pattern) # Output: ---------- word = "Ha" repeated_word = word * 3 print(repeated_word) # Output: HaHaHa Multiplying numbers, strings, and lists: Numbers: Standard arithmetic multiplication. 5 * 3 = 15 Strings: Repeats the string. "abc" * 2 = "abcabc" Lists: Repeats the list elements. (Creates multiple references to the same objects if list contains mutable objects). my_list = [1, 2] * 3 print(my_list) # Output: [1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2] # Caution with mutable objects: list_of_lists = [[0]] * 3 list_of_lists[0][0] = 100 print(list_of_lists) # Output: [[100], [100], [100]] (all sublists changed) Program printing a pattern: size = 5 for i in range(1, size + 1): print(" " * (size - i) + "*" * i) # Output: # * # ** # *** # **** # ***** Q4. String Slicing Definition: Extracting a substring (a "slice") from a string using indices. [start:end] : Extracts characters from start index up to (but not including) end index. If start is omitted, it defaults to 0. If end is omitted, it defaults to the end of the string. s = "Programming" print(s[0:4]) # Output: Prog print(s[4:7]) # Output: ram print(s[:5]) # Output: Progr print(s[7:]) # Output: ming print(s[:]) # Output: Programming (full copy) print(s[1:-1]) # Output: rogrammin [start:end:step] : Same as above, but takes an additional step argument, which specifies how many characters to skip. If step is omitted, it defaults to 1. A negative step reverses the string. s = "Python" print(s[0:6:2]) # Output: Pto (P at 0, t at 2, o at 4) print(s[::2]) # Output: Pto (same as above) print(s[::-1]) # Output: nohtyP (reversed string) print(s[5:0:-1])# Output: nohty (from index 5 down to 1, excluding 0) Programs: Extracting first half and second half: my_str = "HelloWorld" mid = len(my_str) // 2 first_half = my_str[:mid] second_half = my_str[mid:] print(f"Original: {my_str}, First Half: {first_half}, Second Half: {second_half}") # Output: Original: HelloWorld, First Half: Hello, Second Half: World Extracting characters at even indices and odd indices: text = "abcdefg" even_chars = text[::2] # start=0, step=2 odd_chars = text[1::2] # start=1, step=2 print(f"Original: {text}, Even Chars: {even_chars}, Odd Chars: {odd_chars}") # Output: Original: abcdefg, Even Chars: aceg, Odd Chars: bdf Q5. Strings are Immutable in Python Statement: "Strings are immutable in Python" means that once a string object is created, its content (the sequence of characters) cannot be changed. Any operation that appears to modify a string actually creates a new string object. Example: my_string = "hello" # my_string[0] = 'H' # This will raise a TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment print(my_string) # Output: hello (original string is unchanged) new_string = my_string.upper() # .upper() returns a NEW string print(new_string) # Output: HELLO print(my_string) # Output: hello (original 'my_string' is still 'hello') How to modify a string (indirectly): Since you cannot change a string in place, you create a new string based on the original. Concatenation: s1 = "py" s2 = s1 + "thon" # s2 is a new string "python" print(s2) # Output: python Slicing and Concatenation: old_string = "Javapython" # To change "Java" to "Python" new_string = "Python" + old_string[4:] print(new_string) # Output: Pythonpython Using string methods (e.g., replace() ): message = "I like apples." modified_message = message.replace("apples", "bananas") # Returns a new string print(modified_message) # Output: I like bananas. print(message) # Output: I like apples. (original unchanged) Q6. String Formatting Operators Definition: Ways to embed values into string literals. 1. Old style % formatting (printf-style): Uses %s for strings, %d for integers, %f for floats, etc. name = "Alice" age = 30 height = 1.75 print("Name: %s, Age: %d, Height: %.2f" % (name, age, height)) # Output: Name: Alice, Age: 30, Height: 1.75 2. str.format() method: Uses curly braces {} as placeholders. Can be positional or keyword arguments. product = "Laptop" price = 1200.50 print("The {} costs {:.2f} dollars.".format(product, price)) # Output: The Laptop costs 1200.50 dollars. print("Hello {name}, your age is {age}.".format(name="Bob", age=25)) # Output: Hello Bob, your age is 25. 3. f-strings (Formatted String Literals - Python 3.6+): Prefix the string with f or F . Embed expressions directly inside curly braces {} . Most readable and efficient. item = "book" quantity = 2 total = 45.99 print(f"You bought {quantity} {item}s for ${total:.2f}.") # Output: You bought 2 books for $45.99. x = 10 y = 20 print(f"The sum of {x} and {y} is {x + y}.") # Output: The sum of 10 and 20 is 30. Q7. Built-in String Methods 1. .lower() : Returns a new string with all characters converted to lowercase. s = "Hello World" print(s.lower()) # Output: hello world 2. .upper() : Returns a new string with all characters converted to uppercase. s = "Hello World" print(s.upper()) # Output: HELLO WORLD 3. .strip() : Returns a new string with leading and trailing whitespace removed. s = " Python is fun " print(s.strip()) # Output: 'Python is fun' 4. .replace(old, new) : Returns a new string with all occurrences of old substring replaced by new substring. s = "I like apples, apples are good." print(s.replace("apples", "oranges")) # Output: I like oranges, oranges are good. 5. .split(separator) : Splits the string by the specified separator and returns a list of substrings. If no separator, splits by whitespace. s = "apple,banana,cherry" fruits = s.split(',') print(fruits) # Output: ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry'] sentence = "Python is a great language" words = sentence.split() print(words) # Output: ['Python', 'is', 'a', 'great', 'language'] 6. .join(iterable) : Joins elements of an iterable (e.g., list of strings) into a single string, using the string itself as a separator. words = ["Hello", "World"] joined_str = " ".join(words) print(joined_str) # Output: Hello World data = ['1', '2', '3'] csv_str = ','.join(data) print(csv_str) # Output: 1,2,3 Program using three methods: raw_input = " learn python programming " # 1. Strip whitespace cleaned_input = raw_input.strip() # 2. Capitalize first letter capitalized_input = cleaned_input.capitalize() # 3. Replace 'python' with 'Python' final_string = capitalized_input.replace("python", "Python") print(f"Original: '{raw_input}'") print(f"Cleaned: '{cleaned_input}'") print(f"Capitalized: '{capitalized_input}'") print(f"Final: '{final_string}'") # Output: # Original: ' learn python programming ' # Cleaned: 'learn python programming' # Capitalized: 'Learn python programming' # Final: 'Learn Python programming' Q8. ord() and chr() Functions ord(character) : Returns the Unicode (ordinal) integer value of a given character. print(ord('A')) # Output: 65 print(ord('a')) # Output: 97 print(ord('€')) # Output: 8364 chr(integer) : Returns the character represented by the specified Unicode integer value. It's the inverse of ord() . print(chr(65)) # Output: A print(chr(97)) # Output: a print(chr(8364)) # Output: € How these functions compare strings alphabetically: Python compares strings character by character based on their Unicode values. ord() helps to understand this underlying comparison mechanism. A character with a lower Unicode value is considered "smaller" (comes earlier alphabetically). print("apple" The comparison stops at the first differing character. Q9. Iterating Strings and string module Iterating strings using for loop: Iterates over each character in the string. my_string = "Python" for char in my_string: print(char, end=" ") # Output: P y t h o n print() Iterating strings using while loop: Requires manual index management. my_string = "Python" index = 0 while index string module: Provides useful string constants and classes. string.ascii_letters : Contains all ASCII lowercase and uppercase letters. import string print(string.ascii_letters) # Output: abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ string.digits : Contains the string '0123456789'. import string print(string.digits) # Output: 0123456789 string.punctuation : Contains all ASCII punctuation characters. import string print(string.punctuation) # Output: !"#$%&'()*+,-./:; ?@[\]^_`{|}~ Usage example (e.g., password validation/generation): import string import random def generate_strong_password(length=12): characters = string.ascii_letters + string.digits + string.punctuation password = ''.join(random.choice(characters) for i in range(length)) return password print(f"Generated password: {generate_strong_password()}") Q10. The string Module What it is: A built-in Python module that provides a set of useful string constants and some helper functions (though many string manipulations are now done via string methods). Five constants from string module: 1. string.ascii_lowercase : Contains 'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'. Application: Validating if a character is a lowercase letter, generating lowercase random strings. import string print(string.ascii_lowercase) 2. string.ascii_uppercase : Contains 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ'. Application: Similar to lowercase, but for uppercase letters. import string print(string.ascii_uppercase) 3. string.ascii_letters : Concatenation of ascii_lowercase and ascii_uppercase . Application: Checking if a character is any English letter, password generation (as shown in Q9). import string print(string.ascii_letters) 4. string.digits : Contains '0123456789'. Application: Validating if a character is a digit, generating numeric IDs or PINs. import string print(string.digits) 5. string.punctuation : Contains common punctuation characters. Application: Cleaning text by removing punctuation, password generation to increase complexity. import string print(string.punctuation) Example (Password Generation - revisited): import string import random def generate_password(length=10): all_chars = string.ascii_letters + string.digits + string.punctuation if len(all_chars) == 0: # Handle case of empty character set return "" password = ''.join(random.choice(all_chars) for _ in range(length)) return password print(f"Generated password: {generate_password(12)}") This ensures the password contains a mix of character types for strength. UNIT 5: Class and Object Q1. Programming Paradigms & OOP vs. Procedural Programming Paradigms: Fundamental styles of computer programming. Imperative: Focuses on *how* to achieve a result by explicitly stating steps (e.g., procedural, object-oriented). Declarative: Focuses on *what* the program should accomplish without specifying control flow (e.g., functional, logic programming). Procedural: Organizes code into functions/procedures that operate on data. Example: C, Pascal. A script with a main function and several helper functions. Object-Oriented (OOP): Organizes code around "objects" that combine data and the functions that operate on that data. Example: Python, Java, C++. Modeling real-world entities like "Car" with properties (color, speed) and actions (accelerate, brake). Functional: Treats computation as the evaluation of mathematical functions, avoids changing state and mutable data. Example: Haskell, Lisp. Using functions like map() and filter() . OOP vs. Procedural Programming: Feature Procedural Programming Object-Oriented Programming Emphasis Functions/procedures, step-by-step logic. Objects, data and behavior together. Data Handling Data is often global, functions act on it. Data is encapsulated within objects, accessed via methods. Design Top-down approach (decompose into functions). Bottom-up approach (design objects, then build). Modularity Based on functions. Based on objects/classes. Reusability Functions can be reused. Classes can be reused and extended (inheritance). Complexity Can become complex for large systems as data and functions grow independently. Manages complexity well through abstraction and encapsulation. Example A C program calculating taxes with functions like calculate_gross_pay() , calculate_deductions() . A Python program with a Employee class having name , salary attributes and calculate_tax() method. Q2. Main Features of Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) 1. Encapsulation: Bundling data (attributes) and methods (functions) that operate on the data into a single unit (class/object). It hides the internal state of an object from the outside. Example: A Car object encapsulates color , speed (data) and accelerate() , brake() (methods). The user interacts with methods, not directly with internal speed variables. 2. Abstraction: Showing only essential information and hiding complex implementation details. Example: Driving a car. You use the steering wheel, pedals (interface), but don't need to know the complex mechanics of the engine (implementation). A method call like car.start_engine() abstracts away the complex startup sequence. 3. Inheritance: A mechanism where a new class (subclass/derived class) derives properties and behavior from an existing class (superclass/base class). Promotes code reuse. Example: A Dog class and a Cat class can inherit from an Animal class, sharing common attributes like name , age and methods like eat() , sleep() . 4. Polymorphism: "Many forms." The ability of objects of different classes to respond to the same method call in different ways. Example: An Animal class might have a speak() method. A Dog object would implement speak() as "Woof!", while a Cat object would implement it as "Meow!". The call animal.speak() behaves differently depending on the actual type of animal . Q3. Classes and Objects in Python Class: A blueprint or a template for creating objects. It defines a set of attributes (data) and methods (functions) that the objects of that class will have. class Dog: # Class definition # Class attribute species = "Canis familiaris" def __init__(self, name, age): # Constructor method self.name = name # Instance attribute self.age = age # Instance attribute def bark(self): # Instance method return f"{self.name} says Woof!" Object: An instance of a class. It's a concrete entity created from the class blueprint, having its own unique set of attribute values. # Creating objects (instances) of the Dog class my_dog = Dog("Buddy", 3) your_dog = Dog("Lucy", 5) print(my_dog.name) # Output: Buddy print(your_dog.age) # Output: 5 print(my_dog.bark()) # Output: Buddy says Woof! Role of Class Methods, Object Methods, and self keyword: Object (Instance) Methods: Functions defined inside a class that operate on the instance (object) of the class. They always take self as their first parameter, which refers to the instance itself. Example: bark(self) in the Dog class. It uses self.name to access the specific dog's name. Class Methods: Methods that operate on the class itself, rather than on an instance of the class. They are defined using the @classmethod decorator and take cls (conventionally) as their first parameter, which refers to the class. class MyClass: count = 0 # Class attribute def __init__(self): MyClass.count += 1 @classmethod def get_count(cls): return cls.count # Accesses class attribute using cls obj1 = MyClass() obj2 = MyClass() print(MyClass.get_count()) # Output: 2 self keyword: Refers to the instance of the class (the object) on which the method is called. It's the first parameter of all instance methods (including __init__ ). Allows methods to access and modify the instance's attributes (e.g., self.name ). It's a convention; any valid identifier can be used, but self is universally recognized and recommended. Q4. Class Variables and Object Variables Class Variables (Static Variables): Definition: Variables that are shared by all instances (objects) of a class. They are defined directly within the class, outside any method. Access: Accessed using the class name (e.g., ClassName.variable_name ) or through an instance (e.g., object.variable_name , though this can be misleading if an instance variable of the same name exists). Purpose: Store data that is common to all instances or count instances. Example: species and num_of_cars in the example below. Object Variables (Instance Variables): Definition: Variables that are unique to each instance (object) of a class. They are defined inside the constructor ( __init__ method) using the self keyword. Access: Accessed using the instance name (e.g., object.variable_name ). Purpose: Store data that describes the unique state of each individual object. Example: make , model , color in the example below. How they are different (Illustration): class Car: num_of_cars = 0 # Class variable: shared by all Car objects wheels = 4 # Another class variable def __init__(self, make, model, color): self.make = make # Object variable: unique to each car self.model = model # Object variable self.color = color # Object variable Car.num_of_cars += 1 # Increment class variable when new car is created # Create Car objects car1 = Car("Toyota", "Camry", "Blue") car2 = Car("Honda", "Civic", "Red") # Accessing Object Variables print(f"Car 1: {car1.make} {car1.model}, Color: {car1.color}") print(f"Car 2: {car2.make} {car2.model}, Color: {car2.color}") # Accessing Class Variables print(f"Number of cars created: {Car.num_of_cars}") # Output: 2 print(f"Car 1 wheels: {car1.wheels}") # Output: 4 (Accessed via instance, but it's a class var) print(f"Car 2 wheels: {Car.wheels}") # Output: 4 (Accessed via class) # Modifying a Class Variable Car.wheels = 6 # Changes for ALL instances (and future instances) print(f"Car 1 wheels after modification: {car1.wheels}") # Output: 6 print(f"Car 2 wheels after modification: {car2.wheels}") # Output: 6 # If you assign to 'car1.wheels', it creates a new *instance* variable car1.wheels = 8 # This creates a new instance variable 'wheels' for car1 ONLY print(f"Car 1 wheels (instance var): {car1.wheels}") # Output: 8 print(f"Car 2 wheels (still class var): {car2.wheels}") # Output: 6 print(f"Class wheels: {Car.wheels}") # Output: 6 (class variable remains unchanged) Q5. Core Features of Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) 1. Inheritance: (See Q2 for definition and example) class Animal: def __init__(self, name): self.name = name def speak(self): raise NotImplementedError("Subclass must implement abstract method") class Dog(Animal): # Dog inherits from Animal def speak(self): return f"{self.name} says Woof!" class Cat(Animal): # Cat inherits from Animal def speak(self): return f"{self.name} says Meow!" dog = Dog("Buddy") cat = Cat("Whiskers") print(dog.speak()) # Output: Buddy says Woof! print(cat.speak()) # Output: Whiskers says Meow! 2. Polymorphism: (See Q2 for definition and example) # Using the Animal, Dog, Cat classes from above animals = [Dog("Max"), Cat("Bella")] for animal in animals: print(animal.speak()) # Output: # Max says Woof! # Bella says Meow! # The 'speak()' method behaves differently based on the object's type. 3. Encapsulation: (See Q2 for definition and example) class BankAccount: def __init__(self, account_holder, initial_balance=0): self.account_holder = account_holder self.__balance = initial_balance # Private attribute (conventionally) def deposit(self, amount): if amount > 0: self.__balance += amount print(f"Deposited {amount}. New balance: {self.__balance}") else: print("Deposit amount must be positive.") def get_balance(self): return self.__balance # Provides controlled access to balance my_account = BankAccount("Alice", 100) my_account.deposit(50) # Output: Deposited 50. New balance: 150 # print(my_account.__balance) # This would cause an AttributeError (name mangling) print(my_account.get_balance()) # Output: 150 (Controlled access) 4. Data Abstraction: (See Q2 for definition and example) Illustrated by the BankAccount example above, where the user interacts with deposit() and get_balance() without needing to know how __balance is internally managed. 5. Containership (Composition): An object of one class is composed of (contains) objects of another class. Represents a "has-a" relationship. Example: A Car "has an" Engine . class Engine: def __init__(self, horsepower): self.horsepower = horsepower def start(self): return "Engine started." class Car: def __init__(self, make, model, hp): self.make = make self.model = model self.engine = Engine(hp) # Car contains an Engine object def start_car(self): return f"{self.make} {self.model}: {self.engine.start()}" my_car = Car("Tesla", "Model S", 670) print(my_car.start_car()) # Output: Tesla Model S: Engine started. 6. Reusability: The ability to use existing code (classes, methods, functions) multiple times in different parts of a program or in different programs. Example: Inheritance (reusing parent class code) and composition (reusing component classes) are key mechanisms for reusability in OOP. 7. Delegation: An object handles a request by passing it on to another object (the delegate). It's a design pattern that involves one object "delegating" tasks to another. Example: A Printer class might delegate the actual printing task to a low-level PrintDriver class. class PrintDriver: def print_document(self, doc_name): return f"Printing '{doc_name}' using driver." class Printer: def __init__(self): self.driver = PrintDriver() # Printer delegates to PrintDriver def print_job(self, document): return self.driver.print_document(document) my_printer = Printer() print(my_printer.print_job("Report.pdf")) # Output: Printing 'Report.pdf' using driver. UNIT 6: NumPy and Pandas Q1. Understanding NumPy Arrays How NumPy arrays differ from Python lists: Feature NumPy Array ( ndarray ) Python List Data Type Homogeneous (all elements must be of the same type). Heterogeneous (can store elements of different types). Performance Faster for numerical operations (implemented in C). Slower for numerical operations, especially on large data. Memory More memory efficient (stores data contiguously). Less memory efficient (stores pointers to objects). Functionality Optimized for mathematical operations (vectorization, broadcasting). General-purpose sequence, no built-in math operations. Size Fixed size once created (though you can create new ones). Dynamic size (can grow or shrink). Use Case Numerical computing, scientific computing, data analysis. General-purpose data storage, collections of items. Reverse a Vector Using NumPy: import numpy as np # Create a one-dimensional NumPy array (vector) with elements from 1 to 20 original_vector = np.arange(1, 21) # Creates array [1, 2, ..., 20] # Reverse the vector # Slicing with [::-1] creates a reversed view (efficient) reversed_vector = original_vector[::-1] # Display the original and reversed vector print("Original vector:", original_vector) print("Reversed vector:", reversed_vector) Q2. Universal Functions (ufuncs) & Matrix Operations a) What are Universal Functions (ufuncs)? NumPy's "universal functions" are functions that operate on ndarray s in an element-by-element fashion. They are wrappers around compiled C code, making them very fast. They support array broadcasting and type casting. Examples: np.add , np.subtract , np.multiply , np.sin , np.cos , np.sqrt , np.exp . import numpy as np arr = np.array([1, 2, 3]) print(np.sqrt(arr)) # Output: [1. 1.41421356 1.73205081] b) Create a 3x3 matrix with values from 0 to 8: import numpy as np matrix = np.arange(9).reshape(3, 3) # arange(9) creates [0,1,...,8], reshape(3,3) makes it 3x3 print("Matrix:\n", matrix) print("Shape of matrix:", matrix.shape) print("Data type of matrix elements:", matrix.dtype) # Output: # Matrix: # [[0 1 2] # [3 4 5] # [6 7 8]] # Shape of matrix: (3, 3) # Data type of matrix elements: int64 c) Find indices of nonzero elements from [1,2,0,0,4,0] : import numpy as np arr = np.array([1, 2, 0, 0, 4, 0]) nonzero_indices = np.nonzero(arr) print("Original array:", arr) print("Indices of nonzero elements:", nonzero_indices) # Output: # Original array: [1 2 0 0 4 0] # Indices of nonzero elements: (array([0, 1, 4]),) # Note: np.nonzero returns a tuple of arrays, one for each dimension. Q3. Aggregations and Broadcasting in NumPy Aggregation Functions: Functions that compute a single summary statistic from an array of values. min() : Returns the minimum value. max() : Returns the maximum value. mean() : Returns the arithmetic mean. Other common ones: sum() , std() (standard deviation), median() . Broadcasting: A powerful mechanism that allows NumPy to work with arrays of different shapes when performing arithmetic operations. It efficiently extends smaller arrays across larger arrays so that they have compatible shapes. Rule 1: If arrays don't have the same number of dimensions, prepend 1s to the smaller shape until they do. Rule 2: If the size of a dimension doesn't match, and one of them is 1, the array with size 1 is stretched to match the other. Rule 3: If sizes don't match and neither is 1, an error is raised. Python program: import numpy as np matrix = np.array([[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]) print("Original Matrix:\n", matrix) # Row-wise aggregation (axis=1) - operates across columns for each row row_sums = np.sum(matrix, axis=1) row_means = np.mean(matrix, axis=1) print("\nRow Sums:", row_sums) # Output: [ 6 15 24] print("Row Means:", row_means) # Output: [2. 5. 8.] # Column-wise aggregation (axis=0) - operates across rows for each column col_maxes = np.max(matrix, axis=0) col_mins = np.min(matrix, axis=0) print("\nColumn Maxes:", col_maxes) # Output: [7 8 9] print("Column Mins:", col_mins) # Output: [1 2 3] # Broadcasting between arrays of different shapes a = np.array([[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]]) # Shape (2, 3) b = np.array([10, 20, 30]) # Shape (3,) print("\nArray 'a':\n", a) print("Array 'b':", b) # 'b' is broadcast across the rows of 'a' # b (shape (3,)) is treated as (1, 3) and then stretched to (2, 3) result_broadcast = a + b print("\nResult of a + b (broadcasting):\n", result_broadcast) # Output: # [[11 22 33] # [14 25 36]] # Another broadcasting example c = np.array([[10], [20]]) # Shape (2, 1) print("\nArray 'c':\n", c) result_broadcast2 = a + c print("\nResult of a + c (broadcasting):\n", result_broadcast2) # 'c' (shape (2,1)) is stretched to (2,3) to match 'a' # Output: # [[11 12 13] # [24 25 26]] Q4. Comparisons, Masks & Fancy Indexing Comparisons: Element-wise comparisons between arrays or between an array and a scalar. They return boolean arrays. import numpy as np arr = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]) bool_arr = (arr > 3) print(bool_arr) # Output: [False False False True True] Boolean Masks: A boolean array used to select elements from another array. Where the mask is True , the element is selected; where False , it's ignored. data = np.array([10, 20, 30, 40, 50]) mask = np.array([True, False, True, False, True]) filtered_data = data[mask] print(filtered_data) # Output: [10 30 50] Fancy Indexing: Passing an array of indices to select multiple non-contiguous elements. Can use integer arrays for selection. The shape of the result reflects the shape of the index array. data = np.array(['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']) indices = np.array([0, 2, 4]) selected_elements = data[indices] print(selected_elements) # Output: ['a' 'c' 'e'] # Can also use 2D index arrays for 2D arrays matrix = np.array([[10, 11, 12], [20, 21, 22], [30, 31, 32]]) rows_to_select = np.array([0, 2]) cols_to_select = np.array([1, 0]) # Selects (matrix[0,1]) and (matrix[2,0]) selected = matrix[rows_to_select, cols_to_select] print(selected) # Output: [11 30] Code to create mask, filter, and select: import numpy as np data_array = np.array([10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40]) print("Original Data:", data_array) # Create a boolean mask: select elements greater than 20 boolean_mask = (data_array > 20) print("Boolean Mask:", boolean_mask) # Output: Boolean Mask: [False False False True True True True] # Filter values using the mask filtered_values = data_array[boolean_mask] print("Filtered Values (data > 20):", filtered_values) # Output: Filtered Values (data > 20): [25 30 35 40] # Select elements using fancy indexing: indices 0, 3, 5 fancy_indices = np.array([0, 3, 5]) selected_with_fancy_indexing = data_array[fancy_indices] print("Selected with Fancy Indexing (indices 0, 3, 5):", selected_with_fancy_indexing) # Output: Selected with Fancy Indexing (indices 0, 3, 5): [10 25 35] Real-world use cases: Data Cleaning: Filtering out invalid or outlier data points. Feature Selection: Selecting specific columns (features) from a dataset. Conditional Operations: Applying operations only to elements that meet certain criteria (e.g., set all negative values to zero). Image Processing: Selecting pixels based on color channels or brightness. Q5. Sorting NumPy Arrays Different methods of sorting NumPy arrays: np.sort(array) : Returns a sorted copy of the array. Does not modify the original. array.sort() : Sorts the array in-place (modifies the original array) and returns None . np.argsort(array) : Returns the indices that would sort an array. Code to demonstrate: import numpy as np # Original 1-D array arr_1d = np.array([3, 1, 4, 1, 5, 9, 2, 6]) print("Original 1D array:", arr_1d) # Sorting a 1-D array (np.sort vs. .sort()) sorted_arr_copy = np.sort(arr_1d) print("Sorted copy (np.sort):", sorted_arr_copy) print("Original array after np.sort (unchanged):", arr_1d) arr_1d.sort() # In-place sort print("Original array after .sort() (modified):", arr_1d) # Sorting rows and columns of a 2-D array matrix = np.array([[5, 2, 8], [1, 9, 3], [7, 4, 6]]) print("\nOriginal 2D matrix:\n", matrix) # Sort along rows (axis=1) - sorts each row independently sorted_rows = np.sort(matrix, axis=1) print("Sorted along rows (axis=1):\n", sorted_rows) # Output: # [[2 5 8] # [1 3 9] # [4 6 7]] # Sort along columns (axis=0) - sorts each column independently sorted_cols = np.sort(matrix, axis=0) print("Sorted along columns (axis=0):\n", sorted_cols) # Output: # [[1 2 3] # [5 4 6] # [7 9 8]] # Note: 5,4,6 are middle, 7,9,8 are last in their respective columns # Getting sorted index using argsort() arr_val = np.array([30, 10, 40, 20]) sorted_indices = np.argsort(arr_val) print("\nArray for argsort:", arr_val) print("Indices that would sort the array:", sorted_indices) # Output: [1 3 0 2] (10 is at index 1, 20 at 3, 30 at 0, 40 at 2) print("Elements in sorted order using argsort:", arr_val[sorted_indices]) # Output: [10 20 30 40] Q6. Introducing Pandas Objects Pandas Data Structures: Series: A one-dimensional labeled array capable of holding any data type (integers, strings, floats, Python objects, etc.). It's like a column in a spreadsheet or a SQL table. Has a data array and an associated array of labels (index). DataFrame: A two-dimensional labeled data structure with columns of potentially different types. It's like a spreadsheet, a SQL table, or a dictionary of Series objects. Most commonly used Pandas object. Has both a row index and a column index. Python code to create Series and DataFrame: import pandas as pd import numpy as np # Create a Series data_series = pd.Series([10, 20, 30, 40], index=['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']) print("--- Pandas Series ---") print(data_series) print("\nSeries Index:", data_series.index) print("Series Values:", data_series.values) print("Series Data Type:", data_series.dtype) # Output: # a 10 # b 20 # c 30 # d 40 # dtype: int64 # Series Index: Index(['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'], dtype='object') # Series Values: [10 20 30 40] # Series Data Type: int64 # Create a DataFrame from a dictionary data_dict = {'Name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie'], 'Age': [25, 30, 35], 'City': ['NY', 'LA', 'Chicago']} df = pd.DataFrame(data_dict) print("\n--- Pandas DataFrame (from dict) ---") print(df) print("\nDataFrame Index:", df.index) print("DataFrame Columns:", df.columns) print("DataFrame Values (NumPy array):\n", df.values) print("\nDataFrame Data Types:\n", df.dtypes) # Output: # Name Age City # 0 Alice 25 NY # 1 Bob 30 LA # 2 Charlie 35 Chicago # DataFrame Index: RangeIndex(start=0, stop=3, step=1) # DataFrame Columns: Index(['Name', 'Age', 'City'], dtype='object') # DataFrame Values (NumPy array): # [['Alice' 25 'NY'] # ['Bob' 30 'LA'] # ['Charlie' 35 'Chicago']] # # DataFrame Data Types: # Name object # Age int64 # City object # dtype: object # Create a DataFrame from a NumPy array df_from_np = pd.DataFrame(np.random.rand(4, 3), columns=['Col1', 'Col2', 'Col3'], index=['Row1', 'Row2', 'Row3', 'Row4']) print("\n--- Pandas DataFrame (from NumPy array) ---") print(df_from_np) print("\nDataFrame Index:", df_from_np.index) print("DataFrame Columns:", df_from_np.columns) print("DataFrame Data Types:\n", df_from_np.dtypes) Why Pandas is preferred for data analysis: Labeled Data: Data can be accessed by meaningful labels (column names, row indices) instead of just integer positions. Handling Missing Data: Built-in features for easily detecting, filling, or dropping missing values ( NaN ). Data Alignment: Operations between Series/DataFrames with different indices are automatically aligned. Powerful Grouping & Aggregation: groupby() allows for split-apply-combine workflows. Time Series Functionality: Excellent support for time-series data. Integration with NumPy: Built on NumPy, providing high performance for numerical operations. I/O Tools: Easy reading/writing of data from/to various formats (CSV, Excel, SQL, JSON). Q7. Data Indexing, Selection & Operating on Data in Pandas Label-based indexing ( .loc ): Used for selection by label (row/column names). Syntax: df.loc[row_label, column_label] . Inclusive of the end label for slicing. import pandas as pd df = pd.DataFrame({'A': [1, 2, 3], 'B': [4, 5, 6]}, index=['x', 'y', 'z']) print(df.loc['y', 'A']) # Output: 2 print(df.loc['x':'y', 'A':'B']) # Output: # A B # x 1 4 # y 2 5 Position-based indexing ( .iloc ): Used for selection by integer position (0-based indices). Syntax: df.iloc[row_position, column_position] . Exclusive of the end position for slicing (like Python lists). import pandas as pd df = pd.DataFrame({'A': [1, 2, 3], 'B': [4, 5, 6]}, index=['x', 'y', 'z']) print(df.iloc[1, 0]) # Output: 2 (row index 1, col index 0) print(df.iloc[0:2, 0:2]) # Output: # A B # x 1 4 # y 2 5 Code to select rows/columns and perform arithmetic operations: import pandas as pd data = {'Name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie', 'David'], 'Age': [25, 30, 35, 40], 'City': ['NY', 'LA', 'NY', 'Chicago'], 'Salary': [50000, 60000, 75000, 90000]} df = pd.DataFrame(data) print("Original DataFrame:\n", df) # Select a single column print("\n'Name' column:\n", df['Name']) # Returns a Series # Select multiple columns print("\n'Name' and 'City' columns:\n", df[['Name', 'City']]) # Returns a DataFrame # Select rows by index (implicitly uses integer position if no custom index) print("\nFirst two rows (implicit_iloc):\n", df[0:2]) # Select rows using .loc (if custom index) or boolean indexing print("\nRows where City is 'NY' (boolean indexing):\n", df[df['City'] == 'NY']) # Select a specific row and column using .loc print("\nSalary of Alice (using .loc):", df.loc[0, 'Salary']) # Select a specific row and column using .iloc print("\nAge of the first person (using .iloc):", df.iloc[0, 1]) # Perform arithmetic operations on DataFrame columns df['Salary_USD_Equivalent'] = df['Salary'] / 80 # Assuming 1 USD = 80 units df['Age_in_5_Years'] = df['Age'] + 5 print("\nDataFrame after arithmetic operations:\n", df) # Output will show new columns 'Salary_USD_Equivalent' and 'Age_in_5_Years' Q8. Handling Missing Data & Hierarchical Indexing Methods to handle missing data in Pandas: Missing values in Pandas are typically represented by NaN (Not a Number). Detection: .isnull() or .isna() to get a boolean mask, .notnull() or .notna() . Replacement (Imputation): .fillna(value) to replace NaN with a specific value (mean, median, 0, etc.). Dropping: .dropna() to remove rows or columns containing NaN values. Code: import pandas as pd import numpy as np data = {'A': [1, 2, np.nan, 4], 'B': [5, np.nan, 7, 8], 'C': [9, 10, 11, 12]} df_missing = pd.DataFrame(data) print("Original DataFrame with missing values:\n", df_missing) # Detect missing values print("\nMissing values (boolean mask):\n", df_missing.isnull()) print("\nNumber of missing values per column:\n", df_missing.isnull().sum()) # Replace missing values: # 1. Replace with a constant (e.g., 0) df_filled_zero = df_missing.fillna(0) print("\nDataFrame after filling NaN with 0:\n", df_filled_zero) # 2. Replace with mean of the column (for numerical data) df_filled_mean = df_missing.fillna(df_missing.mean(numeric_only=True)) print("\nDataFrame after filling NaN with column mean:\n", df_filled_mean) # Drop missing values: # 1. Drop rows with any NaN df_dropped_rows = df_missing.dropna() print("\nDataFrame after dropping rows with any NaN:\n", df_dropped_rows) # 2. Drop columns with any NaN (axis=1) df_dropped_cols = df_missing.dropna(axis=1) print("\nDataFrame after dropping columns with any NaN:\n", df_dropped_cols) Hierarchical Indexing (MultiIndex): Allows you to have multiple index levels on an axis (rows or columns). Enables working with higher dimensional data in a 2D DataFrame. Example: Storing data for multiple years and multiple states. import pandas as pd # Create a MultiIndex index = pd.MultiIndex.from_product([['California', 'Texas'], [2020, 2021]], names=['State', 'Year']) data = {'Population': [39.5, 39.3, 29.1, 29.5], 'GDP': [3.1, 3.3, 1.8, 1.9]} df_multi = pd.DataFrame(data, index=index) print("\nDataFrame with MultiIndex:\n", df_multi) # Output: # Population GDP # State Year # California 2020 39.5 3.1 # 2021 39.3 3.3 # Texas 2020 29.1 1.8 # 2021 29.5 1.9 # Accessing data with MultiIndex print("\nPopulation for California in 2020:", df_multi.loc[('California', 2020), 'Population']) print("\nAll data for Texas:\n", df_multi.loc['Texas']) Q9. Combining Datasets & Aggregation concat() : Concatenates Pandas objects along a particular axis (rows or columns). Vertical Concatenation (default, axis=0 ): Stacks DataFrames on top of each other. import pandas as pd df1 = pd.DataFrame({'A': [1, 2], 'B': [3, 4]}) df2 = pd.DataFrame({'A': [5, 6], 'B': [7, 8]}) result = pd.concat([df1, df2]) print("Vertical concat:\n", result) # Output: # A B # 0 1 3 # 1 2 4 # 0 5 7 # 1 6 8 Horizontal Concatenation ( axis=1 ): Joins DataFrames side-by-side. df3 = pd.DataFrame({'C': [9, 10], 'D': [11, 12]}) result_h = pd.concat([df1, df3], axis=1) print("\nHorizontal concat:\n", result_h) # Output: # A B C D # 0 1 3 9 11 # 1 2 4 10 12 merge() and join() : Combine DataFrames based on common columns or indices. pd.merge() : Combines DataFrames based on common columns (like SQL joins). how='inner' (default): Only rows with matching keys in both DataFrames. how='left' : Includes all rows from the left DataFrame, and matching rows from the right. df_employees = pd.DataFrame({'emp_id': [1, 2, 3], 'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie']}) df_salaries = pd.DataFrame({'emp_id': [1, 2, 4], 'salary': [50000, 60000, 70000]}) # Inner merge inner_merge = pd.merge(df_employees, df_salaries, on='emp_id', how='inner') print("\nInner Merge:\n", inner_merge) # Output: # emp_id name salary # 0 1 Alice 50000 # 1 2 Bob 60000 # Left merge left_merge = pd.merge(df_employees, df_salaries, on='emp_id', how='left') print("\nLeft Merge:\n", left_merge) # Output (Charlie's salary is NaN): # emp_id name salary # 0 1 Alice 50000.0 # 1 2 Bob 60000.0 # 2 3 Charlie NaN .join() : Primarily used for combining DataFrames based on their indices. df_left = pd.DataFrame({'A': ['A0', 'A1'], 'B': ['B0', 'B1']}, index=['K0', 'K1']) df_right = pd.DataFrame({'C': ['C0', 'C1'], 'D': ['D0', 'D1']}, index=['K0', 'K2']) joined_df = df_left.join(df_right, how='outer') print("\nDataFrame Join (outer):\n", joined_df) # Output: # A B C D # K0 A0 B0 C0 D0 # K1 A1 B1 NaN NaN # K2 NaN NaN C1 D1 Grouping data using groupby() and aggregation functions: groupby() splits a DataFrame into groups based on some criterion. Aggregation functions ( sum() , mean() , count() , min() , max() , size() ) then compute a summary for each group. data = {'City': ['NY', 'LA', 'NY', 'LA', 'NY'], 'Gender': ['M', 'F', 'M', 'M', 'F'], 'Age': [25, 30, 35, 40, 28], 'Salary': [50000, 60000, 75000, 90000, 55000]} df_group = pd.DataFrame(data) print("\nOriginal DataFrame for grouping:\n", df_group) # Group by 'City' and calculate mean age and sum salary grouped_by_city = df_group.groupby('City').agg({'Age': 'mean', 'Salary': 'sum'}) print("\nGrouped by City (Mean Age, Sum Salary):\n", grouped_by_city) # Output: # Age Salary # City # LA 35.0 150000 # NY 29.3 180000 # Group by multiple columns grouped_by_city_gender = df_group.groupby(['City', 'Gender']).mean(numeric_only=True) print("\nGrouped by City and Gender (Mean):\n", grouped_by_city_gender) # Output: # Age Salary # City Gender # LA F 30.0 60000.0 # M 40.0 90000.0 # NY F 28.0 55000.0 # M 30.0 62500.0 Q10. Advanced Pandas Operations 1. Pivot Tables: Used to summarize and reorganize data from a DataFrame. They create a new table that presents the data from a different perspective. `df.pivot_table(values, index, columns, aggfunc)` import pandas as pd data = {'Date': ['2023-01-01', '2023-01-01', '2023-01-02', '2023-01-02'], 'Region': ['East', 'West', 'East', 'West'], 'Sales': [100, 150, 120, 180]} df_sales = pd.DataFrame(data) print("Original Sales Data:\n", df_sales) pivot_table = df_sales.pivot_table(values='Sales', index='Date', columns='Region', aggfunc='sum') print("\nPivot Table (Sales by Date and Region):\n", pivot_table) # Output: # Region East West # Date # 2023-01-01 100 150 # 2023-01-02 120 180 2. Vectorized String Operations: Pandas Series/DataFrame columns containing strings have a .str accessor, which exposes vectorized string methods. This allows applying string operations to entire Series at once, efficiently. import pandas as pd s = pd.Series([' apple ', 'banana ', 'CHERRY']) print("Original Series:\n", s) lower_case = s.str.lower() print("\nLowercase Series:\n", lower_case) # Output: 0 apple , 1 banana , 2 cherry stripped_s = s.str.strip() print("\nStripped Series:\n", stripped_s) # Output: 0 apple, 1 banana, 2 CHERRY contains_a = s.str.contains('a') print("\nContains 'a' Series:\n", contains_a) # Output: 0 True, 1 True, 2 False 3. Working with Time Series: Pandas has robust features for handling date and time data, including parsing, various frequencies, and time-based indexing. import pandas as pd dates = pd.to_datetime(['2023-01-01', '2023-01-02', '2023-01-03']) ts = pd.Series([10, 12, 15], index=dates) print("Time Series:\n", ts) # Extract year/month/day print("\nYears:", ts.index.year) print("Months:", ts.index.month) # Resampling (e.g., daily to weekly) # df_daily = pd.DataFrame({'Value': [1,2,3,4,5]}, index=pd.to_datetime(['2023-01-01', '2023-01-02', '2023-01-03', '2023-01-04', '2023-01-05'])) # weekly_sum = df_daily.resample('W').sum() # print("\nWeekly Sum:\n", weekly_sum) 4. High-Performance Pandas: eval() and query() : These functions allow you to perform operations directly on DataFrame columns using string expressions, which can be much faster for large DataFrames than standard Python operations. .eval() : Evaluates a string expression to compute a new column or modify existing ones. import pandas as pd df_perf = pd.DataFrame(np.random.rand(100000, 3), columns=['A', 'B', 'C']) # Standard Python way # df_perf['D'] = df_perf['A'] + df_perf['B'] / df_perf['C'] # Using .eval() - often faster for large data df_perf.eval('D = A + B / C', inplace=True) print("DataFrame with new column 'D' via eval():\n", df_perf.head()) .query() : Filters a DataFrame by evaluating a boolean expression represented as a string. # Using .query() - often faster for large data filtered_df = df_perf.query('A 0.9') print("\nFiltered DataFrame via query():\n", filtered_df.head())