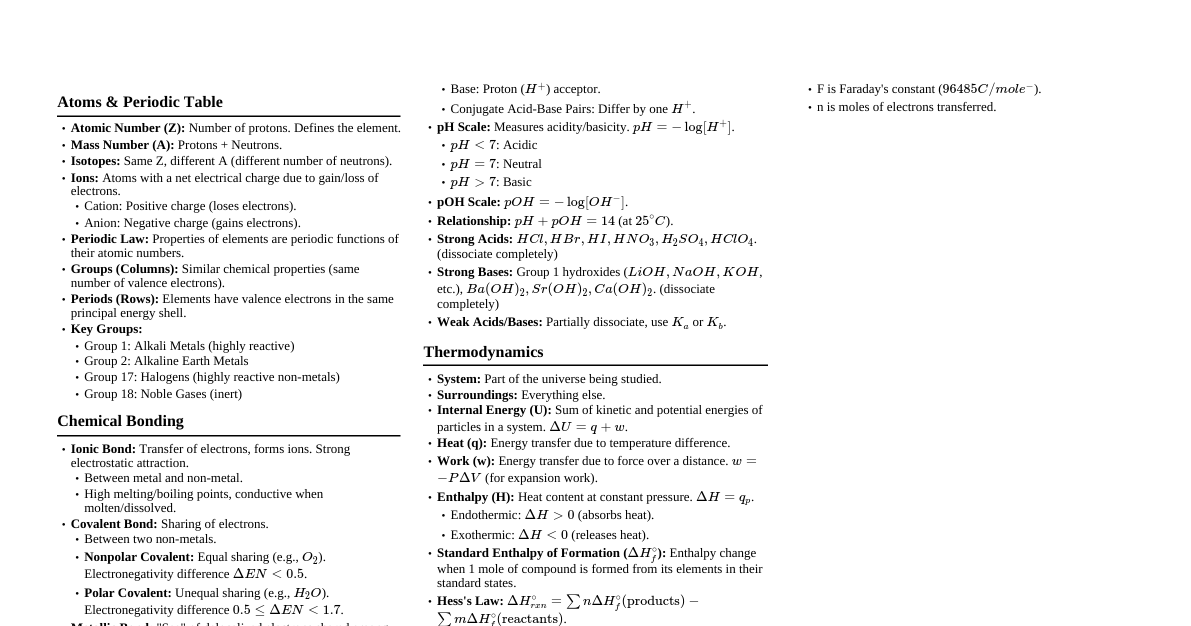

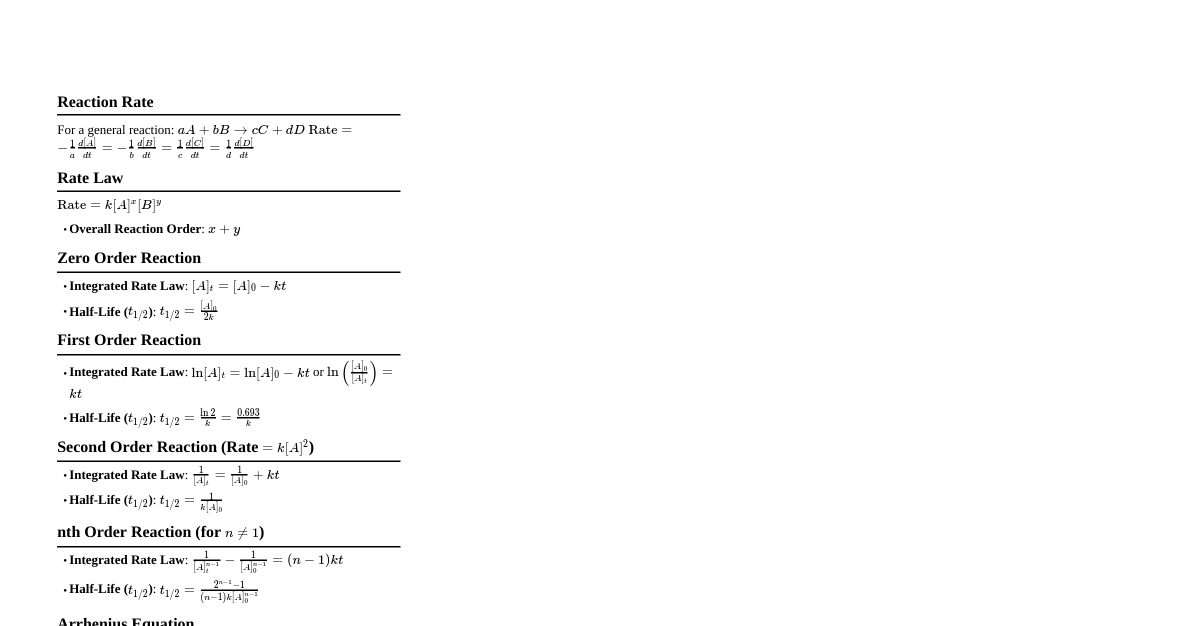

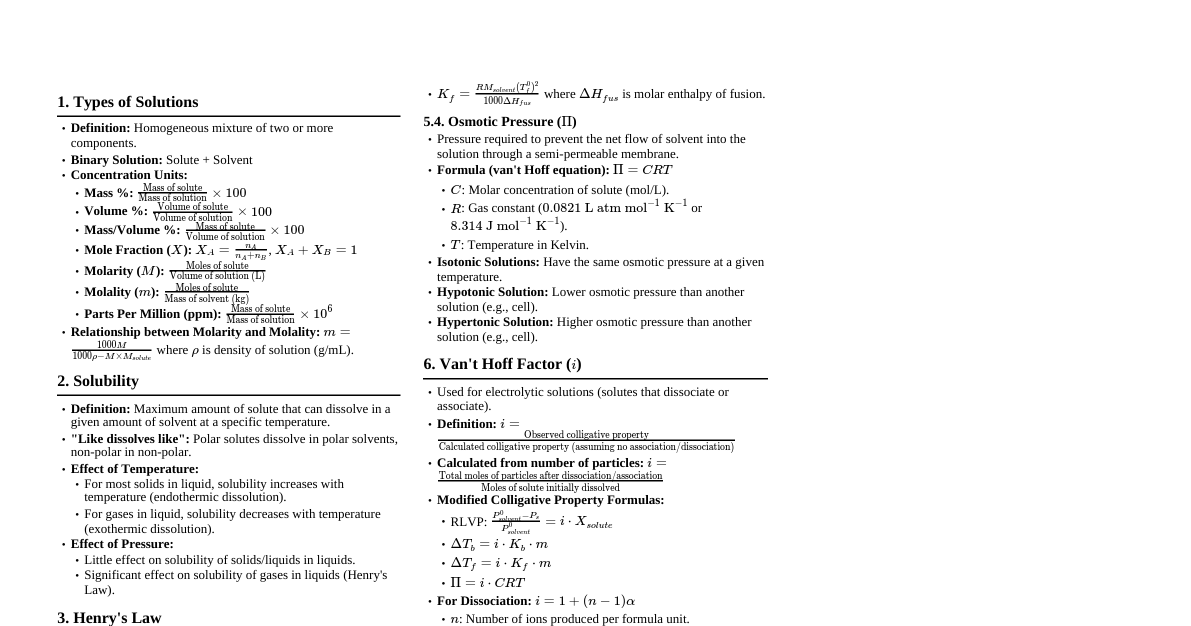

Chemical Kinetics: Introduction Definition: Branch of chemistry dealing with reaction rates and mechanisms. Kinetics vs. Thermodynamics: Thermodynamics predicts feasibility, kinetics predicts speed. Rate of a Chemical Reaction Definition: Change in concentration of a reactant or product per unit time. For $R \to P$: Rate of disappearance of $R = -\frac{\Delta[R]}{\Delta t}$ Rate of appearance of $P = +\frac{\Delta[P]}{\Delta t}$ Average Rate ($r_{av}$): Measured over a time interval $\Delta t$. Instantaneous Rate ($r_{inst}$): Rate at a specific moment, obtained as $\Delta t \to 0$. $r_{inst} = -\frac{d[R]}{dt} = \frac{d[P]}{dt}$. Units: concentration time$^{-1}$ (e.g., mol L$^{-1}$ s$^{-1}$). For gases, atm s$^{-1}$. Stoichiometry: For a reaction $aA + bB \to cC + dD$, Rate $= -\frac{1}{a}\frac{d[A]}{dt} = -\frac{1}{b}\frac{d[B]}{dt} = \frac{1}{c}\frac{d[C]}{dt} = \frac{1}{d}\frac{d[D]}{dt}$ Factors Influencing Rate of Reaction Concentration of reactants Temperature Pressure (for gaseous reactants) Catalyst Rate Expression and Rate Constant Rate Law: Relates reaction rate to reactant concentrations. For $aA + bB \to products$, Rate $= k[A]^x[B]^y$. Rate Constant ($k$): Proportionality constant in the rate law. Order of Reaction: Sum of the exponents in the rate law ($x+y$). Can be 0, 1, 2, 3, or even a fraction. Determined experimentally. Molecularity of a Reaction Definition: Number of reacting species (atoms, ions, or molecules) that must collide simultaneously in an elementary reaction. Types: Unimolecular (1 species), Bimolecular (2 species), Termolecular (3 species). Molecularity vs. Order: Order is experimental; molecularity is theoretical (for elementary steps). Order can be zero or fractional; molecularity cannot. Order applies to elementary and complex reactions; molecularity only to elementary reactions. Rate Determining Step: The slowest step in a complex reaction. Order is given by the molecularity of this step. Integrated Rate Equations Zero Order Reactions Rate is independent of reactant concentration: Rate $= k[R]^0 = k$. Integrated Rate Law: $[R] = -kt + [R]_0$ Rate Constant: $k = \frac{[R]_0 - [R]}{t}$ Half-life ($t_{1/2}$): Time for concentration to reduce to half. $t_{1/2} = \frac{[R]_0}{2k}$. $t_{1/2}$ is directly proportional to initial concentration. Examples: Enzyme-catalyzed reactions, reactions on metal surfaces (e.g., decomposition of $\text{NH}_3$ on Pt). First Order Reactions Rate is proportional to reactant concentration: Rate $= k[R]$. Integrated Rate Law: $\ln[R] = -kt + \ln[R]_0$ or $k = \frac{1}{t} \ln \frac{[R]_0}{[R]}$ Using $\log_{10}$: $k = \frac{2.303}{t} \log \frac{[R]_0}{[R]}$ Half-life ($t_{1/2}$): $t_{1/2} = \frac{0.693}{k}$. $t_{1/2}$ is independent of initial concentration. Examples: Radioactive decay, hydrogenation of ethene. Temperature Dependence: Arrhenius Equation Equation: $k = Ae^{-E_a/RT}$ $k$: rate constant $A$: Arrhenius factor (or frequency factor) $E_a$: activation energy (J mol$^{-1}$) $R$: gas constant $T$: temperature (K) Logarithmic Form: $\ln k = -\frac{E_a}{RT} + \ln A$ Two Temperatures: $\ln \frac{k_2}{k_1} = \frac{E_a}{R} \left( \frac{1}{T_1} - \frac{1}{T_2} \right)$ or $\log \frac{k_2}{k_1} = \frac{E_a}{2.303R} \left( \frac{T_2 - T_1}{T_1 T_2} \right)$ Increasing temperature or decreasing $E_a$ increases reaction rate. Effect of Catalyst Increases reaction rate without undergoing permanent chemical change. Provides an alternate reaction pathway with lower activation energy ($E_a$). Does not alter Gibbs energy ($\Delta G$) or equilibrium constant. Collision Theory Reactant molecules are assumed to be hard spheres that must collide to react. Collision Frequency ($Z$): Number of collisions per unit volume per second. Effective Collisions: Collisions with sufficient kinetic energy (threshold energy) AND proper orientation. Rate Equation: Rate $= P Z_{AB} e^{-E_a/RT}$ $P$: probability (steric) factor, accounts for proper orientation. $Z_{AB}$: collision frequency for reactants A and B. Solutions: Introduction Definition: Homogeneous mixture of two or more components. Components: Solvent: Component in largest quantity, determines physical state. Solute: Other components. Binary Solutions: Contain two components. Types of Solutions Type Solute Solvent Example Gaseous Gas Gas Air ($\text{O}_2 + \text{N}_2$) Liquid Gas Chloroform in $\text{N}_2$ Solid Gas Camphor in $\text{N}_2$ Liquid Gas Liquid $\text{O}_2$ in water Liquid Liquid Ethanol in water Solid Liquid Glucose in water Solid Gas Solid $\text{H}_2$ in Palladium Liquid Solid Amalgam of Mercury with Sodium Solid Solid Copper in Gold Expressing Concentration of Solutions Mass Percentage (w/w): $\frac{\text{Mass of component}}{\text{Total mass of solution}} \times 100$ Volume Percentage (V/V): $\frac{\text{Volume of component}}{\text{Total volume of solution}} \times 100$ Mass by Volume Percentage (w/V): $\frac{\text{Mass of solute}}{\text{Volume of solution}} \times 100$ Parts per Million (ppm): (for trace quantities) $\frac{\text{Number of parts of component}}{\text{Total number of parts of all components}} \times 10^6$ Mole Fraction ($x$): $x_A = \frac{n_A}{n_A + n_B}$. Sum of all mole fractions is 1. Molarity ($M$): $\frac{\text{Moles of solute}}{\text{Volume of solution in Litres}}$. (Temperature dependent) Molality ($m$): $\frac{\text{Moles of solute}}{\text{Mass of solvent in kg}}$. (Temperature independent) Solubility Definition: Maximum amount of solute that can dissolve in a specified amount of solvent at a given temperature. "Like Dissolves Like": Polar solutes dissolve in polar solvents, non-polar in non-polar. Saturated Solution: Contains maximum amount of dissolved solute at equilibrium. Unsaturated Solution: Can dissolve more solute. Solubility of a Solid in a Liquid Effect of Temperature: Endothermic dissolution ($\Delta H_{sol} > 0$): Solubility increases with temperature. Exothermic dissolution ($\Delta H_{sol} Effect of Pressure: Negligible for solids in liquids. Solubility of a Gas in a Liquid Effect of Temperature: Solubility decreases with increasing temperature (exothermic process). Effect of Pressure: Solubility increases with increasing pressure. Henry's Law: Partial pressure of the gas in vapor phase ($p$) is proportional to the mole fraction of the gas in solution ($x$). $p = K_H x$. $K_H$: Henry's Law constant. Higher $K_H$ means lower solubility. Vapour Pressure of Liquid Solutions Raoult's Law (for volatile liquids): For a solution of volatile liquids, the partial vapor pressure of each component is directly proportional to its mole fraction in solution. $p_1 = x_1 p_1^0$ and $p_2 = x_2 p_2^0$ Total pressure: $P_{total} = p_1 + p_2 = x_1 p_1^0 + x_2 p_2^0 = p_1^0 + (p_2^0 - p_1^0)x_2$ Raoult's Law (for non-volatile solute): The relative lowering of vapor pressure is equal to the mole fraction of the solute. $\frac{p_1^0 - p_1}{p_1^0} = x_2$ This equation can be used to determine molar mass of solute: $\frac{p_1^0 - p_1}{p_1^0} = \frac{w_2 M_1}{M_2 w_1}$ Ideal and Non-Ideal Solutions Ideal Solutions: Obey Raoult's law over the entire concentration range. $\Delta H_{mix} = 0$, $\Delta V_{mix} = 0$. Intermolecular forces A-A, B-B, A-B are nearly equal. Examples: n-hexane and n-heptane, benzene and toluene. Non-Ideal Solutions: Do not obey Raoult's law. Positive Deviation: Vapor pressure higher than predicted by Raoult's law. $\Delta H_{mix} > 0$, $\Delta V_{mix} > 0$. A-B interactions are weaker than A-A and B-B. Examples: Ethanol and acetone, carbon disulfide and acetone. Negative Deviation: Vapor pressure lower than predicted by Raoult's law. $\Delta H_{mix} A-B interactions are stronger than A-A and B-B. Examples: Phenol and aniline, chloroform and acetone. Azeotropes: Binary mixtures that boil at a constant temperature and have the same composition in liquid and vapor phases. Cannot be separated by fractional distillation. Colligative Properties Properties that depend on the number of solute particles, not their nature. Used to determine molar masses of solutes. 1. Relative Lowering of Vapour Pressure (RLVP) $\frac{p_1^0 - p_1}{p_1^0} = x_2 = \frac{n_2}{n_1 + n_2}$ 2. Elevation of Boiling Point ($\Delta T_b$) $\Delta T_b = T_b - T_b^0 = K_b m$ $T_b$: boiling point of solution, $T_b^0$: boiling point of pure solvent $K_b$: Molal Elevation Constant (Ebullioscopic Constant) $m$: molality of solution $K_b = \frac{R M_1 T_b^2}{1000 \Delta_{vap}H}$ Molar mass of solute: $M_2 = \frac{1000 K_b w_2}{\Delta T_b w_1}$ 3. Depression of Freezing Point ($\Delta T_f$) $\Delta T_f = T_f^0 - T_f = K_f m$ $T_f$: freezing point of solution, $T_f^0$: freezing point of pure solvent $K_f$: Molal Depression Constant (Cryoscopic Constant) $m$: molality of solution $K_f = \frac{R M_1 T_f^2}{1000 \Delta_{fus}H}$ Molar mass of solute: $M_2 = \frac{1000 K_f w_2}{\Delta T_f w_1}$ 4. Osmotic Pressure ($\Pi$) Pressure that stops the flow of solvent across a semipermeable membrane. $\Pi = CRT = \frac{n_2}{V}RT$ $C$: molar concentration ($n_2/V$) $R$: gas constant $T$: temperature (K) Molar mass of solute: $M_2 = \frac{w_2 RT}{\Pi V}$ Isotonic Solutions: Solutions with the same osmotic pressure at a given temperature. Hypertonic Solution: Higher osmotic pressure, causes cells to shrink (crenation). Hypotonic Solution: Lower osmotic pressure, causes cells to swell (hemolysis). Reverse Osmosis: Solvent flows from solution to pure solvent under external pressure greater than osmotic pressure. Used in desalination. Abnormal Molar Masses (van't Hoff Factor, $i$) Occurs due to dissociation or association of solute particles. van't Hoff Factor ($i$): Ratio of observed colligative property to calculated colligative property (or normal molar mass to abnormal molar mass). $i = \frac{\text{Observed colligative property}}{\text{Calculated colligative property}} = \frac{\text{Normal molar mass}}{\text{Abnormal molar mass}}$ $i > 1$: Dissociation of solute (e.g., NaCl in water, $i \approx 2$) $i Modified Colligative Property Equations: RLVP: $\frac{p_1^0 - p_1}{p_1^0} = i x_2$ Boiling Point Elevation: $\Delta T_b = i K_b m$ Freezing Point Depression: $\Delta T_f = i K_f m$ Osmotic Pressure: $\Pi = i CRT$ Electrochemistry: Introduction Definition: Study of production of electricity from spontaneous chemical reactions and using electrical energy for non-spontaneous reactions. Electrochemical Cells Galvanic (Voltaic) Cell: Converts chemical energy from spontaneous redox reactions into electrical energy. Daniell Cell: $\text{Zn(s)} + \text{Cu}^{2+}\text{(aq)} \to \text{Zn}^{2+}\text{(aq)} + \text{Cu(s)}$ Anode: Electrode where oxidation occurs (negative terminal). Cathode: Electrode where reduction occurs (positive terminal). Salt Bridge: Connects electrolytes, maintains electrical neutrality. Electrolytic Cell: Uses electrical energy to drive non-spontaneous redox reactions. Electrode Potential: Potential difference between electrode and electrolyte. Standard Electrode Potential ($E^0$): Electrode potential when concentrations of all species are unity. Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) is reference $(E^0 = 0 \text{ V})$. Cell EMF ($E_{cell}$): $E_{cell} = E_{right} - E_{left}$ (or $E_{cathode} - E_{anode}$). Nernst Equation Relates electrode potential to ion concentrations. For $\text{M}^{n+}\text{(aq)} + n\text{e}^- \to \text{M(s)}$: $E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{1}{[\text{M}^{n+}]}$ At 298 K: $E = E^0 - \frac{0.059}{n} \log \frac{1}{[\text{M}^{n+}]}$ For a general reaction $a\text{A} + b\text{B} \to c\text{C} + d\text{D}$: $E_{cell} = E_{cell}^0 - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{[\text{C}]^c[\text{D}]^d}{[\text{A}]^a[\text{B}]^b}$ Equilibrium Constant ($K_c$): At equilibrium, $E_{cell} = 0$. $E_{cell}^0 = \frac{RT}{nF} \ln K_c$ At 298 K: $E_{cell}^0 = \frac{0.059}{n} \log K_c$ Gibbs Energy and EMF of Cell Relationship: $\Delta G = -nFE_{cell}$ $\Delta G$: Gibbs energy change $n$: number of moles of electrons transferred $F$: Faraday constant (96487 C mol$^{-1}$) Standard conditions: $\Delta G^0 = -nFE_{cell}^0$ Also, $\Delta G^0 = -RT \ln K_c$ Conductance of Electrolytic Solutions Resistance ($R$): $R = \rho \frac{l}{A}$ (units: Ohm, $\Omega$) Resistivity ($\rho$): Resistance of a conductor 1 m long with 1 m$^2$ cross-section (units: $\Omega$ m). Conductance ($G$): Inverse of resistance. $G = \frac{1}{R}$ (units: Siemens, S or $\Omega^{-1}$). Conductivity ($\kappa$): Inverse of resistivity. $\kappa = \frac{1}{\rho} = G \frac{l}{A}$ (units: S m$^{-1}$ or S cm$^{-1}$). Cell Constant ($G^*$): $\frac{l}{A}$. $\kappa = G \times G^*$. Molar Conductivity ($\Lambda_m$): Conductivity of a solution containing one mole of electrolyte. $\Lambda_m = \frac{\kappa}{C}$ (units: S m$^2$ mol$^{-1}$ or S cm$^2$ mol$^{-1}$). Where $C$ is molar concentration. Variation of Conductivity and Molar Conductivity with Concentration Conductivity ($\kappa$): Decreases with dilution for both strong and weak electrolytes because the number of ions per unit volume decreases. Molar Conductivity ($\Lambda_m$): Increases with dilution. Strong Electrolytes: Increases slowly due to increased ionic mobility. $\Lambda_m = \Lambda_m^0 - A\sqrt{C}$. Weak Electrolytes: Increases sharply due to increased degree of dissociation. Limiting Molar Conductivity ($\Lambda_m^0$): Molar conductivity at infinite dilution ($C \to 0$). Kohlrausch's Law of Independent Migration of Ions: $\Lambda_m^0 = \nu_+ \lambda_+^0 + \nu_- \lambda_-^0$ $\nu_+, \nu_-$: stoichiometric coefficients of cation/anion. $\lambda_+^0, \lambda_-^0$: limiting molar conductivities of cation/anion. Degree of Dissociation ($\alpha$) for Weak Electrolytes: $\alpha = \frac{\Lambda_m}{\Lambda_m^0}$. Dissociation Constant ($K_a$): $K_a = \frac{C \alpha^2}{1-\alpha}$. Electrolysis and Faraday's Laws Electrolysis: Process of using electrical energy to drive non-spontaneous chemical reactions. Faraday's First Law: Amount of chemical reaction at any electrode is proportional to the quantity of electricity passed. $Q = It$. Faraday's Second Law: Amounts of different substances liberated by the same quantity of electricity are proportional to their chemical equivalent weights. 1 Faraday (1 F) = 96487 C (charge of 1 mole of electrons). Batteries Primary Batteries: Non-rechargeable, reaction occurs once. Dry Cell (Leclanché Cell): Zn anode, carbon cathode. Mercury Cell: Zn-Hg amalgam anode, HgO-carbon cathode. Secondary Batteries: Rechargeable. Lead Storage Battery: Lead anode, lead dioxide cathode, $\text{H}_2\text{SO}_4$ electrolyte. Nickel-Cadmium Cell: Cadmium anode, NiO(OH) cathode. Fuel Cells: Convert chemical energy from combustion of fuels directly into electrical energy (e.g., $\text{H}_2-\text{O}_2$ fuel cell). Environmentally friendly. Corrosion Electrochemical phenomenon where metals react with their environment (e.g., rusting of iron). Iron corrosion: Anode (oxidation of Fe), Cathode (reduction of $\text{O}_2$). Prevention: Sacrificial protection, galvanization, painting, oiling, etc.