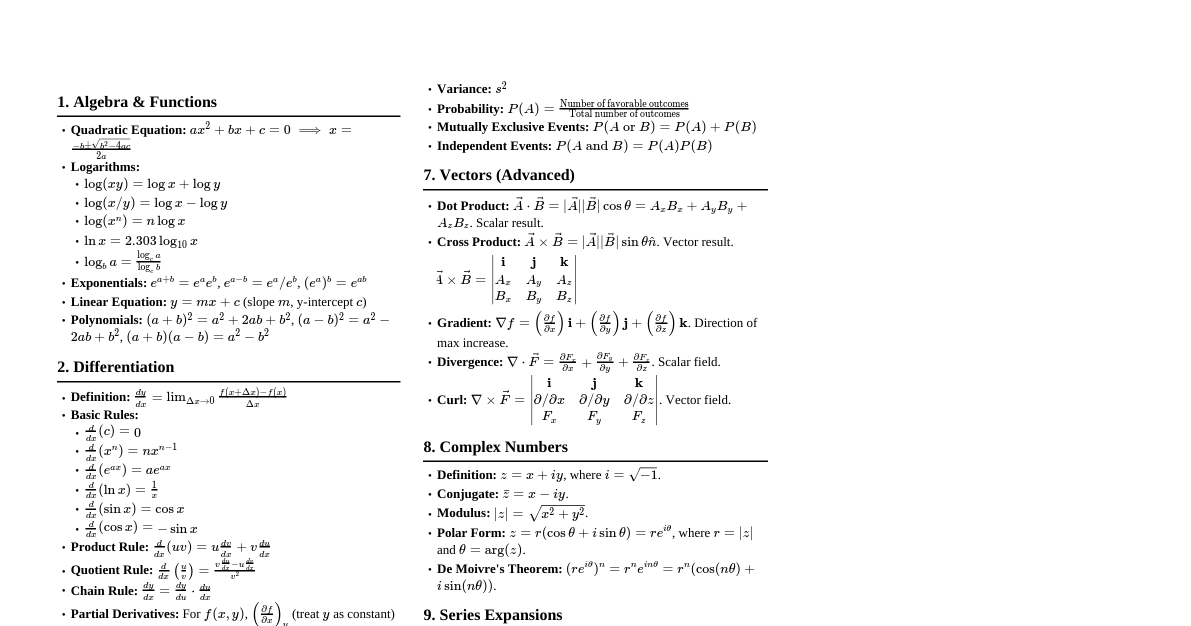

Algebraic Identities: The Building Blocks Think of algebraic identities as special LEGO bricks. Once you know them, you can build complex structures (solve equations) much faster without having to combine individual small pieces every time. $(a+b)^2 = a^2 + 2ab + b^2$ $(a-b)^2 = a^2 - 2ab + b^2$ $(a+b+c)^2 = a^2 + b^2 + c^2 + 2ab + 2bc + 2ca$ $a^2 - b^2 = (a+b)(a-b)$ (Difference of Squares: The classic "break it down" identity) $(a+b)^3 = a^3 + b^3 + 3ab(a+b)$ $(a-b)^3 = a^3 - b^3 - 3ab(a-b)$ $a^3 + b^3 = (a+b)(a^2 - ab + b^2)$ (Sum of Cubes: If you have a sum, you can factor it) $a^3 - b^3 = (a-b)(a^2 + ab + b^2)$ (Difference of Cubes: If you have a difference, you can factor it) $a^3 + b^3 + c^3 - 3abc = (a+b+c)(a^2 + b^2 + c^2 - ab - bc - ca)$ (The "Grand Identity": Often used when $a+b+c=0$) Polynomials & Quadratic Expressions For quadratic expressions $ax^2 + bx + c$: Always Positive: If $a > 0$ and discriminant $D Always Negative: If $a Discriminant: $D = b^2 - 4ac$. It tells you about the nature of the roots. Intervals: Defining Your Playground Intervals are like boundaries for a game. They tell you where your solutions can "play". Open Interval: $(a, b)$ means $a Closed Interval: $[a, b]$ means $a \le x \le b$. The endpoints are included (like a wall you can lean on). Semi-Open/Semi-Closed: $[a, b)$ means $a \le x Infinity: Always use parentheses with $\infty$ or $-\infty$, as infinity is not a number you can "reach" or "include". E.g., $(-\infty, a)$, $[a, \infty)$. Rules for Solving Inequalities: Navigating the Maze Inequalities are like a maze; you need rules to find the exit (solution set). Breaking them can lead you to the wrong path! Multiplying by a Negative: If you multiply or divide both sides by a negative number, you MUST reverse the inequality sign. (Analogy: If you flip a car, everything inside gets inverted!) NEVER Cross-Multiply Variables (Blindly): Only cross-multiply if you are absolutely sure of the variable's sign. If it's positive, the sign stays. If it's negative, the sign flips. If it can be both, you need to consider cases! (Analogy: Don't cross a street with a blindfold on; you need to know if traffic is coming!) Wavy Curve Method: The Signpost on the Number Line The Wavy Curve Method is your GPS for inequalities. It helps you map out where an expression is positive or negative. Factorize: Break down the expression into linear factors (e.g., $(x-a)(x-b)$). Coefficient of $x$ as 1: Make sure the coefficient of $x$ in each factor is positive. If it's negative, factor out $-1$ and remember to adjust the overall sign later. Plot Roots: Mark the roots (values of $x$ that make each factor zero) on a number line. These are your "critical points." Mark Dots/Circles: Use a filled dot for roots where the inequality includes "equal to" ($\le, \ge$) and an empty circle for roots where "equal to" is excluded ($ $). Determine Signs: Start from the rightmost interval (greater than the largest root). Pick a test value and determine the sign of the expression. Power Rule: As you cross a root: If the corresponding factor's power is even , the sign remains the same . (Analogy: An even bounce, like a perfectly elastic ball, doesn't change direction much.) If the corresponding factor's power is odd , the sign changes . (Analogy: An odd bounce, like a deflated ball, changes direction unpredictably.) Select Interval: Choose the intervals that satisfy the original inequality (positive for $>0$, negative for $ Logarithms: The Inverse Power Logarithms are like the "undo" button for exponentiation. If $a^y = x$, then $y = \log_a x$. Base and Argument: In $\log_a x$, $a$ is the base and $x$ is the argument. Domain Constraints (CRITICAL!): For $\log_a x$ to be defined: Argument must be positive: $x > 0$. (You can't take the log of zero or a negative number, just like you can't lift a car with a spoon.) Base must be positive: $a > 0$. Base cannot be one: $a \ne 1$. (If the base is 1, $1^y=x$ implies $x=1$ for any $y$, so it's not a unique inverse.) Log Graph: If $a > 1$, $\log_a x$ is an increasing function. (As $x$ grows, $y$ grows). If $0 All log graphs pass through $(1,0)$ because $\log_a 1 = 0$ for any valid base $a$. Log Properties: The Logarithm's Toolkit These properties are your tools to simplify and solve logarithmic expressions, turning complex problems into simpler ones. $\log_N 1 = 0$ (Any number raised to the power 0 is 1) $\log_N N = 1$ (Any number raised to the power 1 is itself) $\log_b (m/n) = \log_b m - \log_b n$ (Log of a quotient is difference of logs: "Division becomes Subtraction") $\log_b (mn) = \log_b m + \log_b n$ (Log of a product is sum of logs: "Multiplication becomes Addition") $\log_a b = \frac{\log_c b}{\log_c a}$ (Change of Base Formula: Like translating a language to another via a common intermediate) $\log_{a^k} b = \frac{1}{k} \log_a b$ $\log_a (b^k) = k \log_a b$ (Power Rule: The exponent jumps to the front!) $a^{\log_a x} = x$ (The "Undo" Button: Exponential and log functions with the same base cancel each other out) $a^{\log_b c} = c^{\log_b a}$ (Interchange Rule: Bases and arguments can swap places if they are on different sides of the log expression) Logarithmic Inequalities: The Log-Maze Solving inequalities with logarithms involves careful consideration of the base: Constant Base: If $a > 1$: $\log_a x > \log_a y \implies x > y$. The inequality sign stays the same . (Analogy: Everything behaves normally.) If $0 \log_a y \implies x flips . (Analogy: The world is upside down; things go in reverse.) Variable Base: This is trickier! You must consider two cases: Base $a(x) > 1$. Base $0 And always remember the domain constraints for logarithms ($x > 0$, $a(x) > 0$, $a(x) \ne 1$). Modulus Function $y = |x|$: The Absolute Value Guardian The modulus function, $|x|$, is like a guardian that always returns a non-negative value. It makes negatives positive, and positives stay positive. Definition: $$ |x| = \begin{cases} x & \text{if } x \ge 0 \\ -x & \text{if } x Graph: The graph of $y=|x|$ forms a 'V' shape, symmetric about the y-axis, with its vertex at the origin $(0,0)$. Domain: $x \in (-\infty, \infty)$ (All real numbers). Range: $y \in [0, \infty)$ (Only non-negative numbers). Critical Point: The point where the expression inside the modulus becomes zero. For $|x|$, the critical point is $x=0$. These points are where the graph "bends". Modulus Inequalities: The Absolute Rules Solving inequalities with modulus requires breaking them down based on distance from zero. $|x| > k$: Means $x$ is further from zero than $k$. So, $x k$. (Analogy: You're outside the park boundaries.) $|x| Means $x$ is closer to zero than $k$. So, $-k $|a| \le |b|$: Square both sides to remove the modulus: $a^2 \le b^2 \implies a^2 - b^2 \le 0 \implies (a-b)(a+b) \le 0$. This avoids case analysis. (Analogy: Comparing the "size" of two numbers without worrying about their sign, by comparing their squares.)