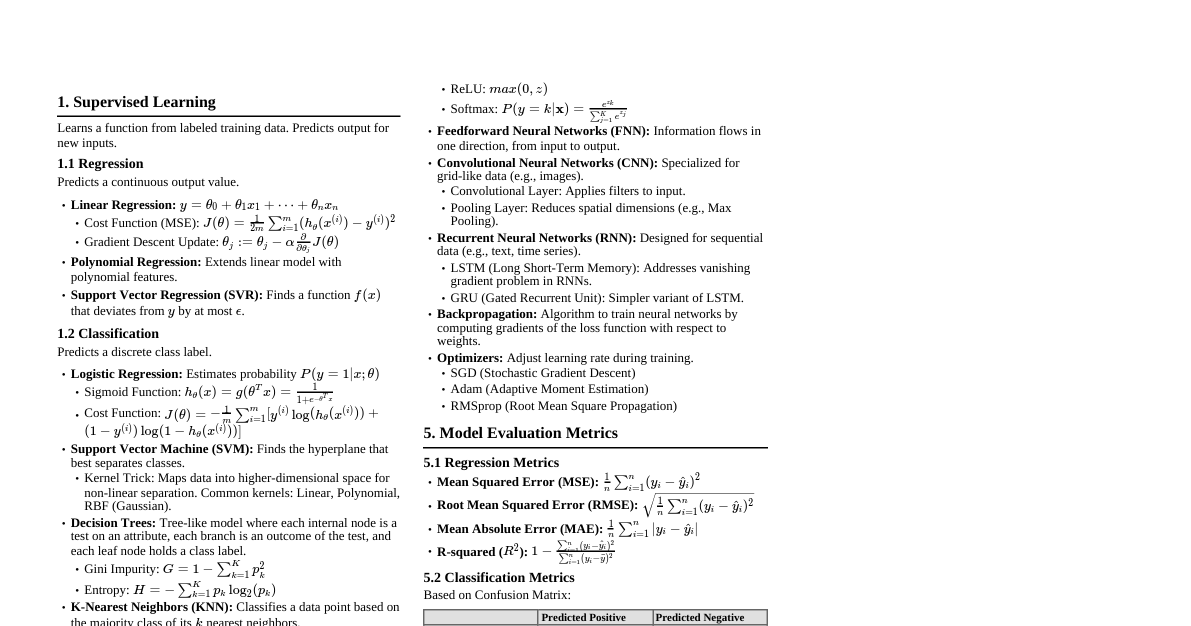

### Introduction to Machine Learning and AI The field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from symbolic reasoning systems to data-driven learning paradigms. Machine Learning (ML), a subset of AI, focuses on systems that learn from data to identify patterns and make decisions with minimal human intervention. #### Evolution of AI The journey of AI can be broadly categorized into several eras: 1. **Symbolic AI (1950s-1980s):** Characterized by rule-based systems and expert systems. AI programs were explicitly programmed with knowledge and logical rules. Examples include ELIZA and early chess programs. 2. **AI Winter (Late 1980s-Early 1990s):** A period of reduced funding and interest due to the limitations of symbolic AI in handling real-world complexity and ambiguity. 3. **Statistical AI/Machine Learning (1990s-2010s):** Emergence of statistical methods and algorithms that learn from data. This era saw the rise of Support Vector Machines (SVMs), decision trees, and Bayesian networks. Increased computational power and data availability fueled this growth. 4. **Deep Learning Revolution (2010s-Present):** Fueled by advances in neural networks, particularly deep neural networks, and massive datasets (Big Data), coupled with powerful GPUs. This led to breakthroughs in image recognition, natural language processing, and speech recognition, pushing AI into the mainstream. 5. **Generative AI/Large Models (2020s-Present):** Focus on models that can generate new content, such as text, images, and code, often based on transformer architectures. Large Language Models (LLMs) are a prime example. #### Four Pillars of Machine Learning Understanding the core components that enable machine learning systems is crucial: 1. **Data:** The raw material for any ML algorithm. Quality, quantity, and relevance of data directly impact model performance. This includes features (input variables) and labels (output variables for supervised learning). 2. **Features:** The measurable properties or attributes of the data. Feature engineering, the process of selecting, transforming, and creating features, is critical for model success. 3. **Model:** The algorithm or mathematical representation that learns patterns from the data. This could be a linear regression model, a decision tree, a neural network, etc. The choice of model depends on the problem type and data characteristics. 4. **Optimization/Learning Algorithm:** The process by which the model adjusts its internal parameters to minimize an error function (loss function) based on the training data. This typically involves iterative methods like gradient descent. ### Types of Machine Learning Machine learning paradigms are categorized by the nature of the learning signal or feedback available to the learner. #### Supervised Learning In supervised learning, the model learns from a labeled dataset, meaning each input example in the training data is paired with an expected output value. The goal is to learn a mapping function from input features to output labels. - **Tasks:** - **Regression:** Predicting a continuous output value (e.g., house prices, temperature). - **Classification:** Predicting a discrete class label (e.g., spam/not spam, cat/dog). - **Examples:** Linear Regression, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines, Decision Trees, Random Forests, Neural Networks. - **Mathematical Foundation:** Given a dataset $\mathcal{D} = \{(x^{(i)}, y^{(i)}) \}_{i=1}^N$, where $x^{(i)} \in \mathbb{R}^d$ are input features and $y^{(i)}$ are target labels. The goal is to learn a function $h: \mathbb{R}^d \to \mathcal{Y}$ that minimizes a loss function $L(y^{(i)}, h(x^{(i)}))$. #### Unsupervised Learning Unsupervised learning deals with unlabeled data. The model tries to find hidden patterns, structures, or relationships within the input data itself, without any explicit output guidance. - **Tasks:** - **Clustering:** Grouping similar data points together (e.g., customer segmentation). - **Dimensionality Reduction:** Reducing the number of features while retaining most of the information (e.g., PCA, t-SNE). - **Association Rule Mining:** Discovering relationships between variables in large databases (e.g., "people who buy X also buy Y"). - **Examples:** K-Means, Hierarchical Clustering, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Autoencoders. - **Mathematical Foundation:** Given a dataset $\mathcal{D} = \{x^{(i)}\}_{i=1}^N$, the goal is to discover underlying structures, such as a latent variable $z^{(i)}$ or a partition $C_k$. This often involves maximizing likelihood or minimizing reconstruction error. #### Semi-Supervised Learning Combines aspects of both supervised and unsupervised learning. It uses a small amount of labeled data and a large amount of unlabeled data for training. This is particularly useful when labeling data is expensive or time-consuming. - **Approach:** Often, the unlabeled data is used to improve the understanding of the data structure, which then helps in improving the performance of the model trained on the labeled data. - **Techniques:** Self-training, co-training, generative models, graph-based methods. #### Reinforcement Learning (RL) In RL, an agent learns to make decisions by interacting with an environment. The agent receives rewards or penalties based on its actions, and its goal is to learn a policy that maximizes the cumulative reward over time. - **Components:** - **Agent:** The learner or decision-maker. - **Environment:** The world the agent interacts with. - **State:** The current situation of the environment. - **Action:** What the agent can do in a given state. - **Reward:** A numerical signal indicating the desirability of an action. - **Policy:** A mapping from states to actions. - **Value Function:** Predicts the future reward from a state-action pair. - **Examples:** Game playing (AlphaGo), robotics, autonomous driving, resource management. - **Mathematical Foundation:** Modeled as a Markov Decision Process (MDP). The agent at state $s_t$ takes action $a_t$, transitions to state $s_{t+1}$, and receives reward $r_t$. The goal is to find a policy $\pi(a|s)$ that maximizes $E[\sum_{t=0}^T \gamma^t r_t]$, where $\gamma$ is the discount factor. #### Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) A form of unsupervised learning where the system generates its own labels from the input data. It creates a "pretext task" where part of the input is used to predict another part, thereby learning useful representations without human-annotated labels. - **Approach:** Learn representations by predicting missing or corrupted parts of the input. - **Examples:** Predicting the next word in a sentence (as in BERT), predicting a rotated image's original orientation, filling in masked patches in an image. - **Benefit:** Enables training large models on vast amounts of unlabeled data, which can then be fine-tuned for downstream supervised tasks with minimal labeled data. #### Active Learning A special case of semi-supervised learning where the learning algorithm can interactively query a user (or other information source) to label new data points. The goal is to achieve high accuracy with as few labeled examples as possible, reducing annotation costs. - **Strategy:** The algorithm identifies the most "informative" unlabeled data points to query for labels (e.g., points close to the decision boundary, or points with highest uncertainty). - **Queries:** Uncertainty sampling, query-by-committee, density-weighted uncertainty sampling. #### Transfer Learning The practice of reusing a pre-trained model on a new, related task. Instead of training a model from scratch, one can leverage the knowledge (learned features, weights) acquired by a model trained on a large dataset for a similar task. - **Process:** Typically, the initial layers of a pre-trained neural network (which learn generic features) are kept fixed or fine-tuned with a low learning rate, while the later layers (which learn task-specific features) are trained on the new, smaller dataset. - **Benefits:** Reduces training time, requires less data, and often leads to better performance, especially when the target task has limited data. #### Metric Learning Focuses on learning a distance function (or similarity measure) between data points. The goal is to learn a metric where similar instances are close together and dissimilar instances are far apart in the learned feature space. - **Applications:** Face recognition, image retrieval, recommendation systems, clustering. - **Techniques:** Siamese networks, triplet loss, contrastive loss. - **Mathematical Foundation:** Learn a transformation $f(x)$ such that a distance $D(f(x_i), f(x_j))$ is small if $x_i$ and $x_j$ are similar, and large otherwise. Often involves learning a Mahalanobis distance. ### The Single Neuron (Perceptron) The single neuron, also known as a perceptron, is the fundamental building block of artificial neural networks. Inspired by biological neurons, it performs a simple computation to make a binary decision. #### Biological Inspiration A biological neuron receives signals through dendrites, processes them in the cell body, and transmits an output signal through the axon. If the sum of incoming signals exceeds a certain threshold, the neuron "fires." #### Mathematical Model A single artificial neuron takes multiple numerical inputs, multiplies each input by a corresponding weight, sums these weighted inputs, adds a bias term, and then passes the result through an activation function to produce an output. Let $x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n$ be the input features. Let $w_1, w_2, \ldots, w_n$ be the corresponding weights. Let $b$ be the bias term. The weighted sum (or net input) $z$ is calculated as: $$z = \sum_{i=1}^{n} w_i x_i + b$$ In vector form: $$z = \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b$$ This weighted sum $z$ is then passed through an activation function $\phi$: $$y = \phi(z) = \phi(\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b)$$ - **Inputs ($x_i$):** Represents features of the data point. - **Weights ($w_i$):** Parameters that determine the strength of the connection between input and neuron. They are learned during training. - **Bias ($b$):** An independent term that shifts the activation function, allowing the neuron to activate even if all inputs are zero. - **Activation Function ($\phi$):** A non-linear function that introduces non-linearity into the model, enabling it to learn complex patterns. Without it, a neural network, no matter how deep, would only be able to learn linear relationships. ##### Common Activation Functions: 1. **Step Function (Heaviside step function):** Used in the original perceptron for binary classification. $$\phi(z) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } z \geq 0 \\ 0 & \text{if } z < 0 \end{cases}$$ This function is not differentiable, making it unsuitable for gradient-based learning. 2. **Sigmoid Function (Logistic Function):** Squashes values between 0 and 1. Used in logistic regression and output layers for binary classification in neural networks. $$\phi(z) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-z}}$$ Its derivative is $\phi'(z) = \phi(z)(1 - \phi(z))$. Suffers from vanishing gradients for very large or very small $z$. 3. **ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit):** Most popular choice for hidden layers. $$\phi(z) = \max(0, z)$$ Its derivative is 1 for $z > 0$ and 0 for $z #### Perceptron Learning Rule The perceptron learning rule is an algorithm for training a single perceptron to classify linearly separable data. It's an iterative algorithm that updates weights based on prediction errors. Given a training example $(\mathbf{x}, y_{true})$: 1. Calculate the predicted output: $y_{pred} = \phi(\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b)$ 2. If $y_{pred} \neq y_{true}$, update weights and bias: $$w_i \leftarrow w_i + \Delta w_i$$ $$b \leftarrow b + \Delta b$$ where the update rule is: $$\Delta w_i = \eta (y_{true} - y_{pred}) x_i$$ $$\Delta b = \eta (y_{true} - y_{pred})$$ Here, $\eta$ is the learning rate, a small positive constant (e.g., 0.01) that controls the step size of the updates. The perceptron convergence theorem states that if the data is linearly separable, the perceptron learning algorithm is guaranteed to converge to a solution in a finite number of steps. However, it cannot learn non-linearly separable patterns (e.g., XOR gate). ### Regression Regression analysis is a set of statistical processes for estimating the relationships between a dependent variable (target) and one or more independent variables (features). The goal is to predict a continuous output. #### Linear Regression Linear regression models the relationship between a scalar dependent variable $y$ and one or more explanatory variables $x$ as a linear function. ##### Simple Linear Regression With one independent variable $x$: $$y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x + \epsilon$$ where: - $y$ is the dependent variable. - $x$ is the independent variable. - $\beta_0$ is the y-intercept (bias). - $\beta_1$ is the slope (weight) of the line. - $\epsilon$ is the error term, representing irreducible error. ##### Multiple Linear Regression With $p$ independent variables $x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_p$: $$y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_2 x_2 + \ldots + \beta_p x_p + \epsilon$$ In vector form, by appending a constant 1 to the feature vector $\mathbf{x}$ for the intercept term: $$\mathbf{x} = [1, x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_p]^T$$ $$\boldsymbol{\beta} = [\beta_0, \beta_1, \ldots, \beta_p]^T$$ Then the model can be written as: $$y = \mathbf{x}^T \boldsymbol{\beta} + \epsilon$$ The objective is to find the coefficients $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ that minimize the sum of squared residuals (SSR), also known as the Mean Squared Error (MSE) for the training data. The cost function $J(\boldsymbol{\beta})$ is: $$J(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \frac{1}{2N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} (y^{(i)} - (\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T \boldsymbol{\beta})^2$$ where $N$ is the number of training examples. The $1/2$ is for mathematical convenience for differentiation. ##### Matrix-Based Solution (Normal Equation) For a dataset with $N$ training examples and $p$ features (plus the intercept term), we can represent the features as a matrix $\mathbf{X}$ and the targets as a vector $\mathbf{y}$. Let $\mathbf{X}$ be an $N \times (p+1)$ matrix where each row is an instance $(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T$. $$\mathbf{X} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & x_{1}^{(1)} & \ldots & x_{p}^{(1)} \\ 1 & x_{1}^{(2)} & \ldots & x_{p}^{(2)} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 1 & x_{1}^{(N)} & \ldots & x_{p}^{(N)} \end{pmatrix}$$ Let $\mathbf{y}$ be an $N \times 1$ vector of target values. $$\mathbf{y} = \begin{pmatrix} y^{(1)} \\ y^{(2)} \\ \vdots \\ y^{(N)} \end{pmatrix}$$ The predicted values are $\hat{\mathbf{y}} = \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}$. The cost function in matrix form is: $$J(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \frac{1}{2N} (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta} - \mathbf{y})^T (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta} - \mathbf{y})$$ To find the $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ that minimizes $J(\boldsymbol{\beta})$, we take the derivative with respect to $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ and set it to zero: $$\frac{\partial J(\boldsymbol{\beta})}{\partial \boldsymbol{\beta}} = \frac{1}{N} \mathbf{X}^T (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta} - \mathbf{y}) = 0$$ $$\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{y}$$ If $\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}$ is invertible, the closed-form solution for $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ is: $$\boldsymbol{\beta} = (\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{y}$$ This is the Normal Equation. - **Advantages:** No need to choose a learning rate, no iteration. - **Disadvantages:** Computationally expensive for large $N$ or $p$ due to matrix inversion ($O(p^3)$ complexity). Fails if $\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}$ is singular (e.g., multicollinearity, $p \ge N$). ##### Gradient Descent Gradient Descent is an iterative optimization algorithm used to find the minimum of a function. For linear regression, it aims to find the $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ that minimizes the MSE cost function. The update rule for each parameter $\beta_j$ is: $$\beta_j \leftarrow \beta_j - \eta \frac{\partial J(\boldsymbol{\beta})}{\partial \beta_j}$$ where $\eta$ is the learning rate. The partial derivative of the cost function with respect to $\beta_j$ is: $$\frac{\partial J(\boldsymbol{\beta})}{\partial \beta_j} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} ((\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T \boldsymbol{\beta} - y^{(i)}) x_j^{(i)}$$ So the update rule for each $\beta_j$ is: $$\beta_j \leftarrow \beta_j - \eta \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} ((\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T \boldsymbol{\beta} - y^{(i)}) x_j^{(i)}$$ This update is performed simultaneously for all $\beta_j$ in each iteration until convergence. - **Batch Gradient Descent:** Uses all $N$ training examples to compute the gradient in each step. Can be slow for large datasets. - **Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD):** Uses only one randomly chosen training example to compute the gradient in each step. Much faster for large datasets, but the updates are noisy, causing the cost function to fluctuate. It eventually converges to a good approximation of the minimum. - **Mini-batch Gradient Descent:** A compromise between Batch GD and SGD. Uses a small random subset (mini-batch) of training examples to compute the gradient. This balances computational efficiency with stability of convergence. ##### Regularization for Linear Regression Regularization techniques are used to prevent overfitting by adding a penalty term to the cost function, discouraging overly complex models. 1. **L1 Regularization (Lasso Regression):** Adds the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients. $$J_{Lasso}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \frac{1}{2N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} (y^{(i)} - (\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T \boldsymbol{\beta})^2 + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^{p} |\beta_j|$$ Lasso can perform feature selection by shrinking some coefficients exactly to zero. 2. **L2 Regularization (Ridge Regression):** Adds the sum of the squares of the coefficients. $$J_{Ridge}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \frac{1}{2N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} (y^{(i)} - (\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T \boldsymbol{\beta})^2 + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j^2$$ Ridge regression shrinks coefficients towards zero but rarely makes them exactly zero. It helps in handling multicollinearity. 3. **Elastic Net Regression:** Combines L1 and L2 regularization. $$J_{ElasticNet}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \frac{1}{2N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} (y^{(i)} - (\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T \boldsymbol{\beta})^2 + \lambda_1 \sum_{j=1}^{p} |\beta_j| + \lambda_2 \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j^2$$ $\lambda, \lambda_1, \lambda_2$ are hyperparameters controlling the strength of regularization. #### Non-Linear Regression When the relationship between variables is not linear, linear models are insufficient. Non-linear regression models capture more complex, curved relationships. ##### Polynomial Regression Models the relationship as an $n$-th degree polynomial. While it fits a non-linear curve, it is still considered a form of linear model in terms of its parameters, as it uses linear combinations of transformed features. $$y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x + \beta_2 x^2 + \ldots + \beta_d x^d + \epsilon$$ Here, $x, x^2, \ldots, x^d$ are considered as new features. The model is linear in the coefficients $\beta_j$. - **Advantage:** Can model complex non-linear relationships. - **Disadvantage:** High degree polynomials can easily overfit the training data. ##### K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) Regression A non-parametric, instance-based learning algorithm. For a new data point, it finds the $k$ nearest data points in the training set and predicts the output as the average (or weighted average) of their target values. - **Algorithm:** 1. Choose the number of neighbors $k$. 2. For a new data point $x_{new}$, calculate its distance to all training points. 3. Select the $k$ training points closest to $x_{new}$. 4. The predicted value $\hat{y}_{new}$ is the average of the target values of these $k$ neighbors: $$\hat{y}_{new} = \frac{1}{k} \sum_{i \in \text{k-neighbors}} y^{(i)}$$ - **Distance Metrics:** Euclidean distance, Manhattan distance, etc. - **Advantages:** Simple, no training phase (lazy learning), can learn complex functions. - **Disadvantages:** Computationally expensive during prediction, sensitive to irrelevant features and scale of features, choice of $k$ is crucial. ##### Support Vector Regression (SVR) An extension of Support Vector Machines (SVMs) for regression tasks. Instead of trying to fit a hyperplane that separates classes, SVR tries to fit a hyperplane that best approximates the continuous target values within a certain margin of tolerance ($\epsilon$). - **Goal:** Find a function $f(\mathbf{x})$ that has at most $\epsilon$ deviation from the actual target $y_i$ for all training data, while being as flat as possible. - **Loss Function:** $\epsilon$-insensitive loss function. It penalizes errors only if they exceed $\epsilon$. $$L_\epsilon(y, f(\mathbf{x})) = \max(0, |y - f(\mathbf{x})| - \epsilon)$$ - **Optimization Problem:** $$\min_{\mathbf{w}, b, \xi, \xi^*} \frac{1}{2} ||\mathbf{w}||^2 + C \sum_{i=1}^N (\xi_i + \xi_i^*)$$ subject to: $$y_i - \mathbf{w}^T \phi(\mathbf{x}_i) - b \le \epsilon + \xi_i$$ $$\mathbf{w}^T \phi(\mathbf{x}_i) + b - y_i \le \epsilon + \xi_i^*$$ $$\xi_i, \xi_i^* \ge 0$$ where: - $\mathbf{w}$ is the weight vector, $b$ is the bias. - $C$ is a regularization parameter (trade-off between flatness and error tolerance). - $\xi_i, \xi_i^*$ are slack variables for errors above and below the $\epsilon$-tube. - $\phi(\mathbf{x}_i)$ is the kernel function mapping data to a higher dimension. - **Kernel Trick:** SVR can use kernel functions (e.g., RBF, polynomial) to implicitly map data into higher-dimensional spaces, allowing it to model non-linear relationships without explicitly computing the transformed features. This is crucial for handling non-linear data efficiently. - **Advantages:** Effective in high-dimensional spaces, robust to outliers (due to $\epsilon$-insensitive loss), uses a subset of training points (support vectors). - **Disadvantages:** Computationally intensive for large datasets, sensitive to hyperparameter choice ($C, \epsilon$, kernel parameters). ##### Decision Tree Regression Decision trees can be used for regression by partitioning the feature space into a set of rectangular regions. For each region, the prediction is the average of the target values of the training points that fall into that region. - **Algorithm:** 1. Start with the entire dataset. 2. Recursively split the data based on features, choosing the split that minimizes the impurity (e.g., Mean Squared Error or Mean Absolute Error) within the resulting child nodes. 3. Continue splitting until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., maximum depth, minimum samples per leaf). 4. For a new data point, traverse the tree to a leaf node and predict the average of targets in that leaf. - **Splitting Criterion (for regression):** Minimize the sum of squared errors (SSE) or MSE. $$J(X_j, t_k) = \frac{N_L}{N} MSE_L + \frac{N_R}{N} MSE_R$$ where $X_j$ is feature $j$, $t_k$ is threshold $k$, $N_L/N_R$ are samples in left/right child, $MSE_L/MSE_R$ are MSE in left/right child. - **Advantages:** Easy to understand and interpret, can handle both numerical and categorical data, implicit feature selection. - **Disadvantages:** Prone to overfitting, high variance (small changes in data can lead to very different trees), sensitive to noisy data. Addressing these often involves ensemble methods like Random Forests or Gradient Boosting. ### Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) A Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) is a class of feedforward artificial neural networks. It consists of at least three layers of nodes: an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each node in one layer connects to every node in the subsequent layer with a certain weight. #### Architecture - **Input Layer:** Receives the input features. The number of nodes equals the number of features in the dataset. No computation is performed here, they just pass the input values to the first hidden layer. - **Hidden Layers:** One or more layers between the input and output layers. These layers perform non-linear transformations on the input data. Each node (neuron) in a hidden layer computes a weighted sum of its inputs, adds a bias, and applies an activation function. The number of hidden layers and nodes per layer are hyperparameters. - **Output Layer:** Produces the final prediction. The number of nodes and the choice of activation function depend on the type of task: - **Regression:** Single node, linear activation (or no activation). - **Binary Classification:** Single node, sigmoid activation (output between 0 and 1). - **Multi-class Classification:** Multiple nodes (one per class), softmax activation (outputs a probability distribution over classes). #### Feedforward Propagation The process of calculating the output of an MLP for a given input is called feedforward propagation. For a neuron $j$ in layer $l$: 1. **Weighted Sum (Net Input):** $$z_j^{(l)} = \sum_{i} w_{ji}^{(l)} a_i^{(l-1)} + b_j^{(l)}$$ where: - $a_i^{(l-1)}$ is the activation of neuron $i$ in the previous layer $(l-1)$. - $w_{ji}^{(l)}$ is the weight connecting neuron $i$ in layer $(l-1)$ to neuron $j$ in layer $l$. - $b_j^{(l)}$ is the bias of neuron $j$ in layer $l$. 2. **Activation:** $$a_j^{(l)} = \phi(z_j^{(l)})$$ where $\phi$ is the activation function. This process propagates from the input layer through all hidden layers to the output layer. #### Backpropagation Backpropagation is the algorithm used to train MLPs by efficiently computing the gradients of the loss function with respect to the weights and biases. It's essentially the chain rule applied to neural networks. **Goal:** Minimize a loss function $L(\mathbf{y}_{true}, \mathbf{y}_{pred})$ by adjusting weights $\mathbf{W}$ and biases $\mathbf{b}$. **Steps:** 1. **Forward Pass:** Compute the output $\mathbf{y}_{pred}$ for a given input $\mathbf{x}$ by propagating activations from input to output layer. Store all intermediate activations and weighted sums. 2. **Compute Output Layer Error ($\delta$):** Calculate the error for the output layer. For a neuron $j$ in the output layer: $$\delta_j^{(L)} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial a_j^{(L)}} \phi'(z_j^{(L)})$$ where $L$ is the loss function, $a_j^{(L)}$ is the activation of the output neuron $j$, and $\phi'$ is the derivative of the activation function. For MSE loss and sigmoid activation: $\delta_j^{(L)} = (a_j^{(L)} - y_j) a_j^{(L)} (1 - a_j^{(L)})$. For CCE loss and softmax activation: $\delta_j^{(L)} = a_j^{(L)} - y_j$. 3. **Backpropagate Error (Hidden Layers):** Compute the error for each hidden layer by propagating the error backwards from the subsequent layer. For a neuron $j$ in hidden layer $l$: $$\delta_j^{(l)} = \left( \sum_{k} w_{kj}^{(l+1)} \delta_k^{(l+1)} \right) \phi'(z_j^{(l)})$$ where the sum is over all neurons $k$ in the next layer $(l+1)$. 4. **Compute Gradients:** Once $\delta$ values are computed for all layers, the gradients for weights and biases can be calculated: $$\frac{\partial L}{\partial w_{ji}^{(l)}} = a_i^{(l-1)} \delta_j^{(l)}$$ $$\frac{\partial L}{\partial b_j^{(l)}} = \delta_j^{(l)}$$ 5. **Update Weights and Biases:** Adjust parameters using an optimization algorithm (e.g., Gradient Descent, Adam): $$w_{ji}^{(l)} \leftarrow w_{ji}^{(l)} - \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial w_{ji}^{(l)}}$$ $$b_j^{(l)} \leftarrow b_j^{(l)} - \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial b_j^{(l)}}$$ where $\eta$ is the learning rate. Backpropagation allows efficient computation of gradients for all parameters in a network, making it feasible to train deep neural networks. #### Universal Approximation Theorem The Universal Approximation Theorem states that a feedforward network with a single hidden layer containing a finite number of neurons can approximate any continuous function on compact subsets of $\mathbb{R}^n$, given appropriate activation functions (e.g., sigmoid, tanh). This means MLPs are theoretically capable of learning arbitrarily complex non-linear relationships. ### Classification Classification is a supervised learning task where the model learns to assign input data points to one of several discrete categories or classes. #### Logistic Regression Despite its name, Logistic Regression is a linear model for **binary classification**. It models the probability that a given input belongs to a particular class using the logistic (sigmoid) function. - **Model:** The linear combination of inputs and weights is first calculated: $$z = \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b$$ This $z$ value is then passed through the sigmoid function to produce a probability: $$\hat{p} = h_{\mathbf{w}, b}(\mathbf{x}) = \sigma(z) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b)}}$$ where $\hat{p}$ is the estimated probability that the instance belongs to class 1. - **Decision Boundary:** If $\hat{p} \ge 0.5$, predict class 1; otherwise, predict class 0. This corresponds to $\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b \ge 0$. The equation $\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b = 0$ defines the linear decision boundary. - **Cost Function (Log Loss / Binary Cross-Entropy):** For a single training example $(\mathbf{x}, y)$, where $y \in \{0, 1\}$: $$L(\hat{p}, y) = -y \log(\hat{p}) - (1-y) \log(1-\hat{p})$$ This function penalizes incorrect predictions. If $y=1$, it penalizes $\log(\hat{p})$ (want $\hat{p}$ close to 1). If $y=0$, it penalizes $\log(1-\hat{p})$ (want $\hat{p}$ close to 0). The overall cost function for $N$ training examples is the average log-loss: $$J(\mathbf{w}, b) = -\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} [y^{(i)} \log(\hat{p}^{(i)}) + (1-y^{(i)}) \log(1-\hat{p}^{(i)})]$$ This cost function is convex, ensuring that gradient descent will find the global minimum. - **Gradient Descent Updates:** The gradients are similar to linear regression, but applied to the sigmoid output. $$\frac{\partial J}{\partial w_j} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} (\hat{p}^{(i)} - y^{(i)}) x_j^{(i)}$$ $$\frac{\partial J}{\partial b} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} (\hat{p}^{(i)} - y^{(i)})$$ Weights and biases are updated iteratively using these gradients. #### Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) Loss Binary Cross-Entropy is the standard loss function for binary classification problems, especially with models that output probabilities (like Logistic Regression or neural networks with a sigmoid output layer). Let $y$ be the true label (0 or 1) and $\hat{y}$ be the predicted probability of class 1. The BCE loss for a single example is: $$L_{BCE}(y, \hat{y}) = -[y \log(\hat{y}) + (1-y) \log(1-\hat{y})]$$ - If $y=1$, $L_{BCE} = -\log(\hat{y})$. This term is minimized when $\hat{y}$ is close to 1. - If $y=0$, $L_{BCE} = -\log(1-\hat{y})$. This term is minimized when $\hat{y}$ is close to 0. The total loss over a dataset is typically the average BCE loss. $$J_{BCE} = -\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} [y^{(i)} \log(\hat{y}^{(i)}) + (1-y^{(i)}) \log(1-\hat{y}^{(i)})]$$ This loss function is derived from the principle of Maximum Likelihood Estimation, assuming the true labels follow a Bernoulli distribution. #### Categorical Cross-Entropy (CCE) Loss Categorical Cross-Entropy (also known as Softmax Loss) is used for multi-class classification problems, where each instance belongs to exactly one class out of $K$ possible classes. It's typically used with a softmax activation function in the output layer of a neural network. Let $y_k$ be a component of the one-hot encoded true label vector $\mathbf{y}$ (i.e., $y_k=1$ if the true class is $k$, and $0$ otherwise). Let $\hat{y}_k$ be the predicted probability that the instance belongs to class $k$, where $\sum_{k=1}^K \hat{y}_k = 1$. The CCE loss for a single example is: $$L_{CCE}(\mathbf{y}, \hat{\mathbf{y}}) = - \sum_{k=1}^{K} y_k \log(\hat{y}_k)$$ Since only one $y_k$ is 1 (for the true class), this simplifies to: $$L_{CCE}(\mathbf{y}, \hat{\mathbf{y}}) = - \log(\hat{y}_{true\_class})$$ This means the loss is simply the negative logarithm of the predicted probability for the correct class. It is minimized when the predicted probability for the true class is close to 1. The total loss over a dataset is the average CCE loss. $$J_{CCE} = -\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sum_{k=1}^{K} y_k^{(i)} \log(\hat{y}_k^{(i)})$$ CCE is also derived from Maximum Likelihood Estimation, assuming the true labels follow a categorical distribution. #### Support Vector Machines (SVM) Support Vector Machines are powerful supervised learning models used for classification (and regression, as seen with SVR). The core idea is to find an optimal hyperplane that maximally separates data points of different classes in the feature space. ##### Linear SVM For binary classification, a linear SVM aims to find a decision boundary defined by the equation $\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b = 0$ such that the margin between the two classes is maximized. The margin is the distance between the hyperplane and the nearest data points from each class (called support vectors). - **Hard Margin SVM (Linearly Separable Data):** If the data is perfectly linearly separable, the objective is to maximize the margin. The margin is $2/||\mathbf{w}||$. Maximizing $2/||\mathbf{w}||$ is equivalent to minimizing $||\mathbf{w}||^2$. The optimization problem is: $$\min_{\mathbf{w}, b} \frac{1}{2} ||\mathbf{w}||^2$$ subject to $y_i (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}_i + b) \ge 1$ for all $i=1, \ldots, N$. This constraint ensures that all data points are correctly classified and lie outside the margin. - **Soft Margin SVM (Non-linearly Separable Data):** In most real-world scenarios, data is not perfectly linearly separable. Soft margin SVM introduces slack variables $\xi_i \ge 0$ to allow some misclassifications or points within the margin. The optimization problem becomes: $$\min_{\mathbf{w}, b, \boldsymbol{\xi}} \frac{1}{2} ||\mathbf{w}||^2 + C \sum_{i=1}^N \xi_i$$ subject to $y_i (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}_i + b) \ge 1 - \xi_i$ for all $i=1, \ldots, N$. Here, $C$ is a regularization hyperparameter: - Small $C$: Allows more misclassifications/margin violations (wider margin, higher bias, lower variance). - Large $C$: Penalizes misclassifications more strongly (narrower margin, lower bias, higher variance). ##### Kernel Trick and RBF Kernel The power of SVMs comes from the "kernel trick," which allows them to efficiently handle non-linearly separable data by implicitly mapping the data into a higher-dimensional feature space where it may become linearly separable. Instead of explicitly computing the transformed features $\phi(\mathbf{x})$, the kernel function $K(\mathbf{x}_i, \mathbf{x}_j) = \phi(\mathbf{x}_i)^T \phi(\mathbf{x}_j)$ computes the dot product in that higher-dimensional space. The dual formulation of the SVM optimization problem only involves dot products of feature vectors, so we can substitute the kernel function. - **Radial Basis Function (RBF) Kernel (Gaussian Kernel):** The RBF kernel is one of the most popular and powerful kernel functions. It measures the similarity between two data points based on their Euclidean distance. $$K(\mathbf{x}_i, \mathbf{x}_j) = \exp(-\gamma ||\mathbf{x}_i - \mathbf{x}_j||^2)$$ where $\gamma > 0$ is a hyperparameter. - **Small $\gamma$:** A large radius of influence, resulting in a smoother decision boundary (less complex model, higher bias, lower variance). - **Large $\gamma$:** A small radius of influence, creating a more complex, wiggly decision boundary (lower bias, higher variance, prone to overfitting). The RBF kernel implicitly maps data into an infinite-dimensional space, allowing SVMs to model very complex non-linear decision boundaries. - **Other Kernels:** - **Polynomial Kernel:** $K(\mathbf{x}_i, \mathbf{x}_j) = (\gamma \mathbf{x}_i^T \mathbf{x}_j + r)^d$ - **Sigmoid Kernel:** $K(\mathbf{x}_i, \mathbf{x}_j) = \tanh(\gamma \mathbf{x}_i^T \mathbf{x}_j + r)$ ##### Advantages and Disadvantages of SVM - **Advantages:** - Effective in high-dimensional spaces. - Still effective in cases where number of dimensions is greater than the number of samples. - Uses a subset of training points (support vectors) in the decision function, making it memory efficient. - Versatile with different kernel functions. - **Disadvantages:** - Can be computationally expensive for very large datasets ($O(N^2)$ to $O(N^3)$). - Performance heavily depends on the choice of kernel and hyperparameters ($C, \gamma$). - Not directly provide probability estimates (though extensions exist). - Less effective with noisy data or overlapping classes. #### Information Gain (IG) Information Gain is a key concept used in the construction of decision trees (for both classification and regression). It quantifies how much "uncertainty" in the target variable is reduced by knowing the value of a feature. The feature that yields the highest information gain is chosen for splitting at each node of the tree. - **Entropy:** A measure of impurity or disorder in a set of data. For a dataset $S$ with $C$ classes, the entropy is defined as: $$H(S) = - \sum_{c=1}^{C} p_c \log_2(p_c)$$ where $p_c$ is the proportion of samples belonging to class $c$ in set $S$. - If $S$ is perfectly pure (all samples belong to one class), $H(S)=0$. - If $S$ is perfectly impure (samples are evenly distributed among classes), $H(S)$ is maximum. - **Information Gain:** The reduction in entropy achieved by splitting a dataset $S$ on a feature $A$. $$IG(S, A) = H(S) - \sum_{v \in \text{Values}(A)} \frac{|S_v|}{|S|} H(S_v)$$ where: - $H(S)$ is the entropy of the parent node (before splitting). - $\text{Values}(A)$ is the set of all possible values for feature $A$. - $S_v$ is the subset of $S$ for which feature $A$ has value $v$. - $|S_v|$ and $|S|$ are the number of samples in $S_v$ and $S$ respectively. The decision tree algorithm at each node selects the feature $A$ that maximizes $IG(S, A)$. This ensures that the most informative features are used to create splits, leading to purer child nodes and a more effective tree. - **Gini Impurity (Alternative to Entropy):** Another common impurity measure, especially used in CART (Classification and Regression Trees) algorithm. $$G(S) = 1 - \sum_{c=1}^{C} p_c^2$$ A split is chosen to minimize the weighted average Gini impurity of the child nodes. ### Ensembling Ensembling is a powerful machine learning technique that combines predictions from multiple individual models (often called "base learners" or "weak learners") to achieve better predictive performance than any single model alone. The core idea is that a group of diverse and reasonably accurate models can collectively make more robust and accurate predictions. #### Bias-Variance Tradeoff Ensembling often helps in managing the bias-variance tradeoff: - **Bias:** Error due to overly simplistic assumptions in the learning algorithm. High bias models tend to underfit. - **Variance:** Error due to excessive sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training data. High variance models tend to overfit. Ensemble methods can reduce bias (e.g., boosting) or variance (e.g., bagging), or both. #### Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) Bagging aims to reduce variance and prevent overfitting. It involves training multiple base learners independently on different subsets of the training data, generated through bootstrapping. - **Bootstrapping:** Creating multiple samples (bootstrapped datasets) from the original training dataset by sampling with replacement. Each bootstrapped sample has the same size as the original dataset, but contains some duplicate instances and misses some original instances. - **Aggregating:** - For **regression:** The final prediction is the average of the predictions from all base learners. - For **classification:** The final prediction is determined by majority voting among the base learners. - **Algorithm:** 1. For $k$ iterations: a. Create a bootstrapped sample $D_k$ from the original training data $D$. b. Train a base learner $h_k$ on $D_k$. 2. For a new input $x$: a. Obtain predictions from all base learners: $h_1(x), h_2(x), \ldots, h_k(x)$. b. Aggregate the predictions (average for regression, majority vote for classification). - **Random Forest:** A popular bagging algorithm that uses decision trees as base learners. It introduces additional randomness by: 1. Bootstrapping the data (as in bagging). 2. At each split in a decision tree, it considers only a random subset of features (e.g., $\sqrt{\text{number of features}}$) rather than all features. This further decorrelates the trees, reducing variance. - **Advantages:** High accuracy, robust to overfitting, handles high-dimensional data, can estimate feature importance. - **Disadvantages:** Less interpretable than single decision trees, can be computationally intensive. #### Boosting Boosting aims to reduce bias and improve accuracy by sequentially building base learners. Each subsequent learner focuses on correcting the errors made by the previous ones. Weak learners are combined to form a strong learner. - **Key Idea:** 1. Train an initial model on the original data. 2. Give more weight to misclassified samples (or higher error samples for regression). 3. Train a new model on the re-weighted data. 4. Repeat, and combine the models, giving more weight to better-performing models. - **AdaBoost (Adaptive Boosting):** One of the earliest and most influential boosting algorithms. 1. Initialize equal weights for all training samples. 2. For $t = 1, \ldots, T$ (number of weak learners): a. Train a weak learner $h_t$ (e.g., a shallow decision tree, called a "stump") on the current weighted training data. b. Calculate the error rate $\epsilon_t$ of $h_t$. c. Calculate the weight $\alpha_t$ of $h_t$ in the final ensemble: $\alpha_t = \frac{1}{2} \log\left(\frac{1 - \epsilon_t}{\epsilon_t}\right)$. d. Update the weights of the training samples: increase weights for misclassified samples, decrease for correctly classified samples. Normalize weights. 3. Final prediction: A weighted majority vote of all weak learners: $H(x) = \text{sign}\left(\sum_{t=1}^T \alpha_t h_t(x)\right)$. - **Gradient Boosting:** A more general boosting framework. Instead of re-weighting instances, it trains each new model to predict the *residuals* (errors) of the previous model. 1. Start with an initial model $F_0(x)$ (e.g., a constant value, the average target). 2. For $m = 1, \ldots, M$: a. Compute the "pseudo-residuals" (gradients of the loss function with respect to the previous prediction) for each data point: $r_{im} = -\left[\frac{\partial L(y_i, F(x_i))}{\partial F(x_i)}\right]_{F(x)=F_{m-1}(x)}$. b. Train a new weak learner $h_m(x)$ (e.g., a decision tree) to fit these residuals. c. Update the ensemble model: $F_m(x) = F_{m-1}(x) + \nu h_m(x)$, where $\nu$ is a learning rate (shrinkage). 3. Final prediction: $F_M(x)$. - **Examples:** Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost. These are highly popular and powerful algorithms in competitive machine learning. - **Advantages:** Highly accurate, can handle various data types, robust to outliers (with appropriate loss functions). - **Disadvantages:** Prone to overfitting if not carefully tuned, computationally intensive, less interpretable. #### Stacking (Stacked Generalization) Stacking combines multiple diverse models by training a "meta-learner" (or blender) to make the final prediction based on the predictions of the individual base learners. - **Algorithm:** 1. **Level 0 Models (Base Learners):** Train several diverse base models (e.g., SVM, K-NN, Random Forest) on the original training data. 2. **Generate New Features:** For each base model, predict the output for the entire training set (often using k-fold cross-validation to prevent data leakage). These predictions become the new "features" for the meta-learner. 3. **Level 1 Model (Meta-Learner):** Train a meta-learner (e.g., Logistic Regression, a simple neural network) on the output predictions (new features) from the base models, with the original target variable. 4. **Prediction:** To make a prediction on new unseen data, first get predictions from all base learners. Then, feed these predictions as input to the meta-learner to get the final output. - **Advantages:** Can achieve higher accuracy than bagging or boosting by leveraging the strengths of different types of models. - **Disadvantages:** More complex to implement, computationally expensive, requires careful prevention of data leakage. ### Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a widely used unsupervised linear dimensionality reduction technique. Its primary goal is to transform a high-dimensional dataset into a lower-dimensional one while retaining as much of the variance (information) as possible. #### Motivation for Dimensionality Reduction - **Curse of Dimensionality:** As the number of features (dimensions) increases, the data becomes sparse, making it harder for algorithms to find meaningful patterns. - **Computational Efficiency:** Reducing dimensions can significantly speed up training and inference of machine learning models. - **Noise Reduction:** Removing redundant or noisy features can improve model performance. - **Visualization:** High-dimensional data is hard to visualize. PCA can project data into 2D or 3D for plotting. - **Storage:** Less memory required to store the data. #### Core Idea of PCA PCA finds a new set of orthogonal axes (principal components) in the data that capture the maximum variance. The first principal component (PC1) captures the most variance, the second (PC2) captures the second most variance orthogonal to PC1, and so on. #### Mathematical Formulation Given a dataset $\mathbf{X}$ of $N$ samples and $D$ features, with each row $\mathbf{x}_i \in \mathbb{R}^D$: 1. **Standardize the Data:** PCA is sensitive to the scale of features. It's crucial to standardize the data (mean-center and scale to unit variance) before applying PCA. $$\mathbf{x}_{centered}^{(j)} = \mathbf{x}^{(j)} - \mu_j$$ $$\mathbf{x}_{scaled}^{(j)} = \frac{\mathbf{x}^{(j)} - \mu_j}{\sigma_j}$$ where $\mu_j$ is the mean and $\sigma_j$ is the standard deviation of feature $j$. For simplicity in the following steps, assume data $\mathbf{X}$ is already centered. 2. **Compute the Covariance Matrix:** The covariance matrix $\mathbf{C}$ (size $D \times D$) measures the relationships between all pairs of features. $$\mathbf{C} = \frac{1}{N-1} \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}$$ (If data is centered, $\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}$ is proportional to the covariance matrix). The diagonal elements are variances, and off-diagonal elements are covariances. 3. **Compute Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors:** Find the eigenvalues $\lambda_k$ and corresponding eigenvectors $\mathbf{v}_k$ of the covariance matrix $\mathbf{C}$. $$\mathbf{C} \mathbf{v}_k = \lambda_k \mathbf{v}_k$$ - **Eigenvectors:** These are the principal components. They represent the directions of maximum variance in the data. They are orthogonal. - **Eigenvalues:** These represent the amount of variance captured by each principal component. A larger eigenvalue means its corresponding eigenvector captures more variance. 4. **Select Principal Components:** Sort the eigenvectors in descending order according to their corresponding eigenvalues. The eigenvector with the largest eigenvalue is PC1, the second largest is PC2, and so on. Choose the top $k$ eigenvectors (principal components) that explain a sufficient amount of variance (e.g., 95%). This forms the projection matrix $\mathbf{W}$ (size $D \times k$). $$\mathbf{W} = [\mathbf{v}_1, \mathbf{v}_2, \ldots, \mathbf{v}_k]$$ 5. **Project Data to Lower Dimension:** Transform the original centered data $\mathbf{X}$ into the new $k$-dimensional subspace using the projection matrix $\mathbf{W}$. $$\mathbf{Z} = \mathbf{X} \mathbf{W}$$ where $\mathbf{Z}$ is the $N \times k$ matrix of transformed data, with $k$ principal components. #### Interpreting Principal Components - Each principal component is a linear combination of the original features. - The coefficients of the linear combination (the values in the eigenvector) indicate the contribution of each original feature to that principal component. - PC1 usually represents the most dominant direction of variation. For example, in a dataset of house features, PC1 might represent overall size/luxury. #### Choosing the Number of Components ($k$) 1. **Scree Plot:** Plot the eigenvalues in descending order. Look for an "elbow" point where the eigenvalues start to level off. 2. **Explained Variance Ratio:** Calculate the proportion of variance explained by each component: $\frac{\lambda_k}{\sum_{j=1}^D \lambda_j}$. Sum these ratios to find the cumulative explained variance. Choose $k$ such that the cumulative explained variance reaches a desired threshold (e.g., 95%). $$\text{Cumulative Explained Variance} = \frac{\sum_{j=1}^k \lambda_j}{\sum_{j=1}^D \lambda_j}$$ #### Advantages and Disadvantages of PCA - **Advantages:** - Reduces dimensionality, combating the curse of dimensionality. - Removes correlated features (principal components are orthogonal). - Can improve model performance by reducing noise and overfitting. - Useful for data visualization. - **Disadvantages:** - **Loss of Interpretability:** Principal components are linear combinations of original features, making them harder to interpret than original features. - **Information Loss:** Some information is always lost during dimensionality reduction. - **Linearity Assumption:** PCA only finds linear relationships between features. For non-linear structures, other techniques like Kernel PCA or t-SNE might be more suitable. - **Sensitive to Scaling:** Requires feature scaling. - **Does not consider target variable:** PCA is unsupervised, meaning it might retain variance that is irrelevant to a supervised learning task.