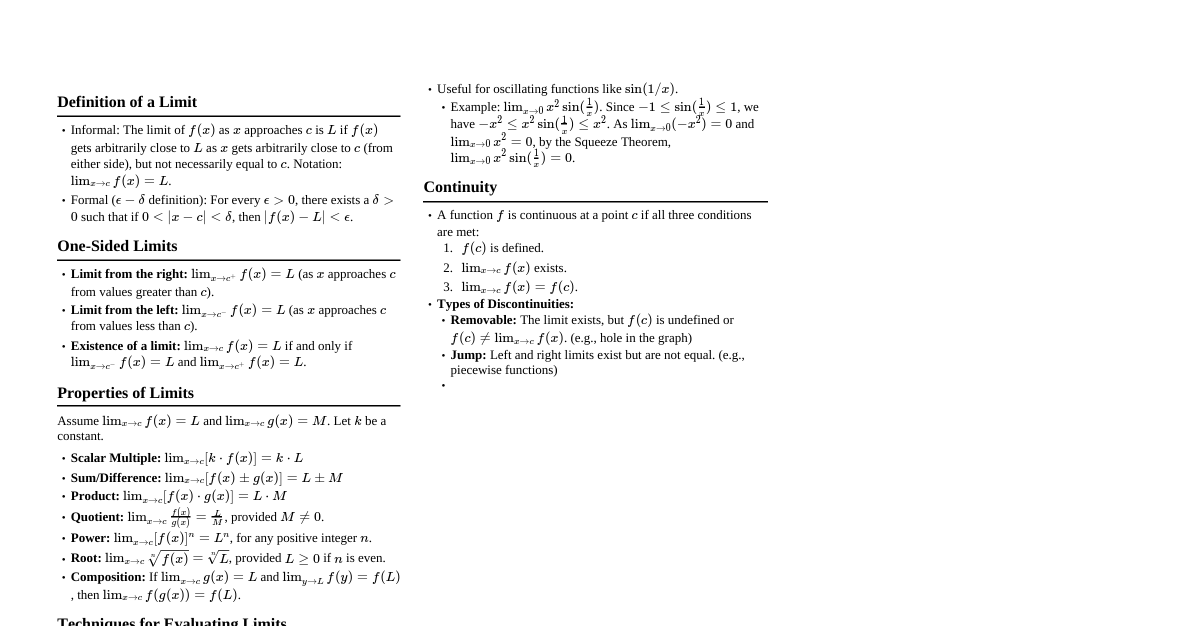

1 Limits and Continuity 1.1 Limit of a Function: An Intuitive Approach Definition (Intuitive): Let $f$ be a function defined on some open interval $I$ containing $a$, except possibly at $a$. We say that the limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ approaches $a$ is $L$, where $L \in \mathbb{R}$, denoted $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L$, if we can make $f(x)$ as close to $L$ as we like by taking values of $x$ sufficiently close to $a$ (but not necessarily equal to $a$). Remark: Alternatively, $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L$ if the values of $f(x)$ get closer and closer to $L$ as $x$ assumes values going closer and closer to $a$ but not reaching $a$. Note: In finding the limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ tends to $a$, we only need to consider values of $x$ that are very close to $a$ but not exactly $a$. This means that the limit may exist even if $f(a)$ is undefined. Note: If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ and $f(a)$ both exist, their values may not be equal. It is possible that $f(a) \neq \lim_{x \to a} f(x)$. Note: If $f(x)$ does not approach a real number as $x$ tends to $a$, then we say that the limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ approaches $a$ does not exist. 1.1.2 Evaluating Limits Theorem 1.1.10 (Limit Laws): Let $f(x)$ and $g(x)$ be functions defined on some open interval containing $a$, except possibly at $a$. If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ exists, then it is unique. If $c \in \mathbb{R}$, then $\lim_{x \to a} c = c$. $\lim_{x \to a} x = a$. Suppose $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L_1$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = L_2$ where $L_1, L_2 \in \mathbb{R}$, and $c \in \mathbb{R}$. $\lim_{x \to a} [f(x) + g(x)] = L_1 + L_2$ $\lim_{x \to a} [cf(x)] = cL_1$ $\lim_{x \to a} [f(x)g(x)] = L_1L_2$ $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \frac{L_1}{L_2}$, provided that $g(x) \neq 0$ on some open interval containing $a$, except possibly at $a$, and $L_2 \neq 0$. $\lim_{x \to a} [f(x)]^n = (L_1)^n$ for $n \in \mathbb{N}$. $\lim_{x \to a} \sqrt[n]{f(x)} = \sqrt[n]{L_1}$ for $n \in \mathbb{N}, n > 1$ and provided that $L_1 > 0$ when $n$ is even. Theorem 1.1.14: Let $f$ be a polynomial or a rational function. If $a \in \text{dom } f$, then $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = f(a)$. 1.1.3 Other Techniques in Evaluating Limits Indeterminate Form of type $0/0$: If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = 0$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = 0$, then $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$ is called an indeterminate form of type $\frac{0}{0}$. Remark: The term "indeterminate" only applies to the limit $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$, and not the function value $\frac{f(a)}{g(a)}$. Remark: A limit that is indeterminate of type $\frac{0}{0}$ may exist, and to compute the limit, one may use cancellation of common factors and rationalization of expressions (if applicable). 1.2 One-Sided Limits Limit from the left: Let $f$ be a function defined at every number in some open interval $(c, a)$. We say that the limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ approaches $a$ from the left is $L$, denoted $\lim_{x \to a^-} f(x) = L$, if the values of $f(x)$ get closer and closer to $L$ as the values of $x$ get closer and closer to $a$, but are less than $a$. Limit from the right: Let $f$ be a function defined at every number in some open interval $(a, c)$. We say that the limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ approaches $a$ from the right is $L$, denoted $\lim_{x \to a^+} f(x) = L$, if the values of $f(x)$ get closer and closer to $L$ as the values of $x$ get closer and closer to $a$, but are greater than $a$. Remark 1.2.3: The conclusions in Theorem 1.1.10 still hold when "$x \to a$" is replaced by "$x \to a^-$" or "$x \to a^+$". We sometimes refer to $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ as the two-sided limit to distinguish it from one-sided limits. Definition (Approach to 0 from positive/negative values): Suppose $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = 0$. If $f$ approaches $0$ through positive values, we write $f(x) \to 0^+$. Similarly, if $f$ approaches $0$ through negative values, we write $f(x) \to 0^-$. Remark 1.2.6: If $f(x) \to 0^+$ as $x \to a$, and $n$ is even, then $\lim_{x \to a} \sqrt[n]{f(x)} = 0$. If $f(x) \to 0^-$ as $x \to a$, and $n$ is even, then $\lim_{x \to a} \sqrt[n]{f(x)}$ does not exist. Theorem 1.2.10: $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L$ if and only if $\lim_{x \to a^-} f(x) = L = \lim_{x \to a^+} f(x)$. 1.3 Limits Involving Infinity Definition (Positive Infinity): Let $f$ be a function defined on some open interval containing $a$, except possibly at $a$. We say that the limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ approaches positive infinity is $L$, denoted $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = +\infty$, if the value of $f(x)$ increases without bound whenever the values of $x$ get closer and closer to $a$ (but does not reach $a$). Definition (Negative Infinity): Also, we say that the limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ approaches $a$ is negative infinity, denoted $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = -\infty$, if the value of $f(x)$ decreases without bound whenever the values of $x$ get closer and closer to $a$ (but does not reach $a$). Remark 1.3.2: The expressions above with "$x \to a$" replaced by "$x \to a^-$" or "$x \to a^+$" are similarly defined. Remark 1.3.4: Note that $\infty$ is not a real number. Thus, if $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = +\infty$ or $-\infty$, we do not mean that the limit exists. Though the limit does not exist, through the symbol we are able to describe the behavior of $f$ near $a$: that it increases or decreases indefinitely as $x \to a$. Theorem 1.3.5: Let $c$ be a nonzero real number. Suppose $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = c$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = 0$. If $c > 0$, and $g(x) \to 0^+$ as $x \to a$, then $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = +\infty$. and $g(x) \to 0^-$ as $x \to a$, then $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = -\infty$. If $c and $g(x) \to 0^+$ as $x \to a$, then $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = -\infty$. and $g(x) \to 0^-$ as $x \to a$, then $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = +\infty$. Theorem 1.3.7 (Properties of Infinite Limits): If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ exists and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = \pm\infty$, then $\lim_{x \to a} (f(x) + g(x)) = \pm\infty$. If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ exists and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = \pm\infty$, then $\lim_{x \to a} (f(x) - g(x)) = \mp\infty$. If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = +\infty$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = +\infty$, then $\lim_{x \to a} (f(x) + g(x)) = +\infty$. If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = +\infty$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = -\infty$, then $\lim_{x \to a} (f(x) - g(x)) = +\infty$ and $\lim_{x \to a} (g(x) - f(x)) = -\infty$. Let $c \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \{0\}$. Suppose $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = c$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = \pm\infty$. Then $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)g(x) = \pm\infty$, if $c > 0$. $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)g(x) = \mp\infty$, if $c Definition (Vertical Asymptote): The line $x = a$ is a vertical asymptote of the graph of $y = f(x)$ if at least one of the following is true: $\lim_{x \to a^-} f(x) = -\infty$ $\lim_{x \to a^-} f(x) = +\infty$ $\lim_{x \to a^+} f(x) = -\infty$ $\lim_{x \to a^+} f(x) = +\infty$ Indeterminate form of type $\infty - \infty$: If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = +\infty$ while $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = -\infty$, then $\lim_{x \to a} [f(x) - g(x)]$ is called an indeterminate form of type $\infty - \infty$. Indeterminate form of type $0 \cdot \infty$: If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = 0$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = \pm\infty$, then $\lim_{x \to a} [f(x)g(x)]$ is called an indeterminate form of type $0 \cdot \infty$. 1.3.2 Limits at Infinity Definition (Limit to a real number L): Let $f$ be a function defined at every number in some interval $(a, \infty)$. We say that the limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ approaches positive infinity is $L$, denoted $\lim_{x \to +\infty} f(x) = L$, if the values of $f(x)$ get closer and closer to $L$ as the values of $x$ increase without bound. Definition (Limit to a real number L from negative infinity): Similarly, let $f$ be a function defined at every number in some interval $(-\infty, a)$. We say that the limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ approaches negative infinity is $L$, denoted $\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = L$, if the values of $f(x)$ get closer and closer to $L$ as the values of $x$ decrease without bound. Remark 1.3.14: We have similar notions for the following symbols: $\lim_{x \to +\infty} f(x) = +\infty$ or $-\infty$ $\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = +\infty$ or $-\infty$ Theorem 1.3.16: Let $n$ be a positive integer. $\lim_{x \to +\infty} x^n = +\infty$, if $n$ is even. $\lim_{x \to +\infty} x^n = +\infty$, if $n$ is odd. $\lim_{x \to +\infty} \frac{1}{x^n} = 0$. Let $c \in \mathbb{R}$. Suppose $\lim_{x \to +\infty} f(x) = c$ and $\lim_{x \to +\infty} g(x) = \pm\infty$. Then $\lim_{x \to +\infty} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = 0$. Remark 1.3.17: In statement 4 of the previous theorem, "$x \to +\infty$" may be replaced by "$x \to -\infty$", "$x \to a^-$", "$x \to a^+$", and "$x \to a$". What is important is that the limit of the numerator exists, while the denominator increases or decreases without bound. Remark 1.3.20 (Limits of Polynomial Functions): In general, to find $\lim_{x \to \pm\infty} f(x)$ if $f$ is a polynomial function, it suffices to consider the behavior of the leading term of $f(x)$ as $x \to \pm\infty$. Indeterminate form of type $\infty/\infty$: If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = \pm\infty$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = \pm\infty$, then $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$ is called an indeterminate form of type $\infty/\infty$. Definition (Horizontal Asymptote): The line $y = L$ is a horizontal asymptote of the graph of $y = f(x)$ if $\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = L$ or $\lim_{x \to +\infty} f(x) = L$. Definition (Oblique Asymptote): The graph of $f$ has the line $y = mx + b$, $m \neq 0$, as an oblique asymptote if at least one of the following is true: $\lim_{x \to +\infty} [f(x) - (mx + b)] = 0$ $\lim_{x \to -\infty} [f(x) - (mx + b)] = 0$ 1.4 Limit of a Function: The Formal Definition Definition (Formal Definition of Limit): Let $f(x)$ be a function defined on some open interval containing $a$, except possibly at $a$. The limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ approaches $a$ is $L$, written $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L$, if and only if for every $\epsilon > 0$ (no matter how small) there exists a $\delta > 0$ such that $|f(x) - L| Remark: The absolute value inequalities represent open intervals "centered" at $L$ and at $a$. The formal definition then says this: for any open interval $I_{\epsilon}$ centered at $L$, there is a corresponding open interval $I_{\delta}$ "centered" at $a$ such that whenever $x$ is in $I_{\delta}$ (but $x \neq a$), $f(x)$ is guaranteed to be in $I_{\epsilon}$. Remark 1.4.5: The value of $\delta$ is not unique. Note that if a given $\delta$ works such that if $0 Remark 1.4.7: If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L$, observe that in one way or another, the expression $|x - a|$ can be factored from the expression $|f(x) - L|$. This means that if $0 1.5 Continuity of Functions; The Intermediate Value Theorem Continuity at a Point: A function $f$ is said to be continuous at $x = a$ if the following conditions are all satisfied: $f$ is defined at $x = a$ $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ exists $f(a) = \lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ Otherwise, $f$ is said to be discontinuous at $x = a$. Remark 1.5.3: In general, if $f$ is a polynomial or a rational function and $a$ is any element in the domain of $f$, then $f$ is continuous at $x = a$. Definition (Types of Discontinuity): If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ exists but either $f(a)$ is undefined or $f(a) \neq \lim_{x \to a} f(x)$, then we say that $f$ has a removable discontinuity at $x = a$. If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ does not exist, then we say that $f$ has an essential discontinuity at $x = a$. Moreover, if $\lim_{x \to a^-} f(x)$ and $\lim_{x \to a^+} f(x)$ both exist but are not equal, then $f$ is said to have a jump essential discontinuity at $x = a$. if $\lim_{x \to a^-} f(x) = \pm\infty$ or $\lim_{x \to a^+} f(x) = \pm\infty$, then $f$ is said to have an infinite essential discontinuity . Remark 1.5.7: The removable discontinuity can be "removed" by redefining $f(a)$ so that $f(a) = \lim_{x \to a} f(x)$. Remark 1.5.10: The discontinuities of a given function $f$ may occur at points where $f$ is undefined or, for piecewise functions, at the endpoints of intervals. Such points are aptly called the possible points of discontinuity of $f$. Theorem 1.5.11 (Properties of Continuous Functions): Let $f$ and $g$ be continuous at $x = a$ and let $c \in \mathbb{R}$. Then the following are also continuous at $x = a$: $f + g$ $f - g$ $fg$ $\frac{f}{g}$, provided that $g(a) \neq 0$ $cf$ Continuity from the left: A function $f$ is said to be continuous from the left at $x = a$ if $f(a) = \lim_{x \to a^-} f(x)$. Continuity from the right: A function $f$ is said to be continuous from the right at $x = a$ if $f(a) = \lim_{x \to a^+} f(x)$. Continuity on an Interval: A function $f$ is said to be continuous: everywhere if $f$ is continuous at every real number. on $(a, b)$ if $f$ is continuous at every point $x$ in $(a, b)$. on $[a, b)$ if $f$ is continuous on $(a, b)$ and from the right of $a$. on $(a, b]$ if $f$ is continuous on $(a, b)$ and from the left of $b$. on $[a, b]$ if $f$ is continuous on $(a, b]$ and on $[a, b)$. on $(a, \infty)$ if $f$ is continuous at all $x > a$. on $[a, \infty)$ if $f$ is continuous on $(a, \infty)$ and from the right of $a$. on $(-\infty, b)$ if $f$ is continuous at all $x on $(-\infty, b]$ if $f$ is continuous on $(-\infty, b)$ and from the left of $b$. Remark 1.5.14: Polynomial functions are continuous everywhere. The absolute value function $f(x) = |x|$ is continuous everywhere. Rational functions are continuous on their respective domains. The square root function $f(x) = \sqrt{x}$ is continuous on $[0, \infty)$. The greatest integer function $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$ is continuous on $[n, n+1)$, where $n$ is any integer. Theorem 1.5.15 (Composition of Continuous Functions): If $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = b$ and $f$ is continuous at $b$, then $\lim_{x \to a} f(g(x)) = f(b)$. In other words, if $f$ is continuous at $\lim_{x \to a} g(x)$, then $\lim_{x \to a} f(g(x)) = f(\lim_{x \to a} g(x))$. Theorem 1.5.18 (Composition of Continuous Functions): If $g$ is continuous at $x = a$ and $f$ is continuous at $g(a)$, then $(f \circ g)(x) = f(g(x))$ is continuous at $x = a$. Theorem 1.5.22 (Intermediate Value Theorem (IVT)): Let $f$ be continuous on a closed interval $[a, b]$ with $f(a) \neq f(b)$. For every $k$ between $f(a)$ and $f(b)$, there exists $c$ in $(a, b)$ such that $f(c) = k$. Remark 1.5.23: The continuity of the function on $[a, b]$ in IVT is required. In general, the theorem is not true for functions that are discontinuous on $[a, b]$. The number $c$ in the conclusion of IVT may not be unique. 1.6 Trigonometric Functions: Limits and Continuity; The Squeeze Theorem Theorem 1.6.1 (Squeeze Theorem): Let $f(x)$, $g(x)$ and $h(x)$ be defined on some open interval $I$ containing $a$ except possibly at $x = a$ such that $f(x) \le g(x) \le h(x)$, for all $x \in I \setminus \{a\}$. If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ and $\lim_{x \to a} h(x)$ both exist and are both equal to $L \in \mathbb{R}$, then $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = L$. Remark 1.6.2: With some modifications, "$x \to a$" can be replaced by "$x \to a^-$", "$x \to a^+$", "$x \to +\infty$" and "$x \to -\infty$". Theorem 1.6.6 (Special Trigonometric Limits): $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\sin x}{x} = 1$ $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1 - \cos x}{x} = 0$ $\lim_{x \to 0} \sin x = 0$ $\lim_{x \to 0} \cos x = 1$ Remark 1.6.8: $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{x}{\sin x} = 1$. Theorem 1.6.15 (Continuity of Trigonometric Functions): For all $a \in \mathbb{R}$, $\lim_{x \to a} \cos x = \cos a$ and $\lim_{x \to a} \sin x = \sin a$. The trigonometric functions are continuous on their respective domains. Remark 1.6.16: If $f$ is a trigonometric function and $a \in \text{dom } f$, then $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = f(a)$. 1.6.1 Trigonometric Identities Reciprocal Identities: $\csc x = \frac{1}{\sin x}$ $\sec x = \frac{1}{\cos x}$ $\cot x = \frac{1}{\tan x}$ Quotient Identities: $\tan x = \frac{\sin x}{\cos x}$ $\cot x = \frac{\cos x}{\sin x}$ Pythagorean Identities: $\sin^2 x + \cos^2 x = 1$ $1 + \tan^2 x = \sec^2 x$ $1 + \cot^2 x = \csc^2 x$ Even/Odd Identities: $\sin(-x) = -\sin x$ (odd) $\cos(-x) = \cos x$ (even) $\tan(-x) = -\tan x$ (odd) Cofunction Identities: $\sin(\frac{\pi}{2} - x) = \cos x$ $\cos(\frac{\pi}{2} - x) = \sin x$ $\tan(\frac{\pi}{2} - x) = \cot x$ Sum and Difference Identities: $\sin(A \pm B) = \sin A \cos B \pm \cos A \sin B$ $\cos(A \pm B) = \cos A \cos B \mp \sin A \sin B$ $\tan(A \pm B) = \frac{\tan A \pm \tan B}{1 \mp \tan A \tan B}$ Double Angle Identities: $\sin(2x) = 2 \sin x \cos x$ $\cos(2x) = \cos^2 x - \sin^2 x = 2 \cos^2 x - 1 = 1 - 2 \sin^2 x$ $\tan(2x) = \frac{2 \tan x}{1 - \tan^2 x}$ Half Angle Identities: $\sin^2 x = \frac{1 - \cos(2x)}{2}$ $\cos^2 x = \frac{1 + \cos(2x)}{2}$ $\tan^2 x = \frac{1 - \cos(2x)}{1 + \cos(2x)}$ Product-to-Sum Identities: $\sin A \cos B = \frac{1}{2}[\sin(A+B) + \sin(A-B)]$ $\cos A \sin B = \frac{1}{2}[\sin(A+B) - \sin(A-B)]$ $\cos A \cos B = \frac{1}{2}[\cos(A+B) + \cos(A-B)]$ $\sin A \sin B = \frac{1}{2}[\cos(A-B) - \cos(A+B)]$ Sum-to-Product Identities: $\sin A + \sin B = 2 \sin(\frac{A+B}{2}) \cos(\frac{A-B}{2})$ $\sin A - \sin B = 2 \cos(\frac{A+B}{2}) \sin(\frac{A-B}{2})$ $\cos A + \cos B = 2 \cos(\frac{A+B}{2}) \cos(\frac{A-B}{2})$ $\cos A - \cos B = -2 \sin(\frac{A+B}{2}) \sin(\frac{A-B}{2})$ 1.7 New Classes of Functions: Limits and Continuity 1.7.1 Inverse Functions Definition (Inverse Functions): If the functions $f$ and $g$ satisfy $(f \circ g)(x) = x$ for all $x \in \text{dom } g$, and $(g \circ f)(x) = x$ for all $x \in \text{dom } f$, then we say $f$ and $g$ are inverse functions of each other. We write $g = f^{-1}$ or $f = g^{-1}$. Definition (One-to-one function): A function $f$ is a one-to-one function if for all $x_1, x_2 \in \text{dom } f$ with $x_1 \neq x_2$, $f(x_1) \neq f(x_2)$. Remark 1.7.2 (Horizontal Line Test): A function is one-to-one if and only if no horizontal line intersects its graph more than once. Theorem 1.7.3: A function $f$ has an inverse if and only if it is one-to-one. Remark 1.7.5: Let $f$ be a one-to-one function. We have $y = f(x)$ if and only if $x = f^{-1}(y)$. The domains and range of $f$ and $f^{-1}$ are related. Indeed, $\text{dom } f^{-1} = \text{ran } f$ and $\text{ran } f^{-1} = \text{dom } f$. The graph of $f^{-1}$ is obtained by reflecting the graph of $f$ about the line $y = x$. We have the following cancellation equations: $f^{-1}(f(x)) = x$ for all $x \in \text{dom } f$, $f(f^{-1}(x)) = x$ for all $x \in \text{dom } f^{-1}$. To find the inverse function $f^{-1}$, we write $y = f(x)$ and then solve for $x$ in terms of $y$ to obtain $x = f^{-1}(y)$. Finally, interchange $x$ and $y$ to get $y = f^{-1}(x)$. 1.7.2 Exponential and Logarithmic Functions Definition (Exponential Function): Let $a > 0$ and $a \neq 1$. The exponential function with base $a$ is given by $f(x) = a^x$, where $x \in \mathbb{R}$. Remark 1.7.7: Let $f(x) = a^x$ with $a > 0$ and $a \neq 1$. Then we have the following: $\text{dom } f = \mathbb{R}$ and $\text{ran } f = (0, +\infty)$. $f$ is one-to-one and continuous on $\mathbb{R}$. If $a > 1$, then $f$ is increasing on $\mathbb{R}$. $\lim_{x \to +\infty} a^x = +\infty$ and $\lim_{x \to -\infty} a^x = 0$. If $0 Definition (Logarithmic Function): Let $a > 0$ and $a \neq 1$. The logarithmic function with base $a$, denoted by $\log_a$, is the inverse function of the exponential function with base $a$; that is, $y = \log_a x$ if and only if $x = a^y$. Remark 1.7.8: Let $f(x) = \log_a x$ with $a > 0$ and $a \neq 1$. Then we have the following: $\text{dom } f = (0, +\infty)$ and $\text{ran } f = \mathbb{R}$. $f$ is one-to-one and continuous on $(0, +\infty)$. If $a > 1$, then $f$ is increasing on $(0, +\infty)$. $\lim_{x \to +\infty} \log_a x = +\infty$ and $\lim_{x \to 0^+} \log_a x = -\infty$. If $0 Table 1.7.1 (Laws of Exponents and Logarithms): Exponents ($a, b > 0, r, s \in \mathbb{R}$) Logarithms ($a, b, m, n > 0, a, b \neq 1$) $a^0 = 1, a^1 = a$ $\log_a 1 = 0$ $a^r a^s = a^{r+s}$ $\log_a a = 1$ $\frac{a^r}{a^s} = a^{r-s}$ $\log_a (mn) = \log_a m + \log_a n$ $(a^r)^s = a^{rs}$ $\log_a (\frac{m}{n}) = \log_a m - \log_a n$ $(ab)^x = a^x b^x$ $\log_a (m^c) = c \log_a m$ $(\frac{a}{b})^x = \frac{a^x}{b^x}$ $\log_a m = \frac{\log_b m}{\log_b a}$ $\log_a m = \frac{1}{\log_m a}$ Definition (Euler's number $e$): $e = \lim_{h \to 0} (1+h)^{1/h}$. Remark 1.7.14: The number $e$ is irrational, and to the first 15 decimal places, $e \approx 2.718281828459045...$. The natural exponential function is given by $f(x) = e^x$. The natural logarithmic function is given by $f(x) = \ln x = \log_e x$. Remark 1.7.15: Let $a, b > 0$ and $a, b \neq 1$. Then we have the following: $\ln e^x = x$ for all $x \in \mathbb{R}$. $e^{\ln x} = x$ for all $x > 0$. $\ln e = 1$. $a^x = e^{\ln a^x} = e^{x \ln a} = (e^x)^{\ln a}$ for all $x \in \mathbb{R}$. $\log_a x = \frac{\log_b x}{\log_b a} = \frac{\ln x}{\ln a}$ for all $x > 0$. 1.7.3 Inverse Circular Functions 1. Inverse sine function: $y = \sin^{-1} x$ if and only if $x = \sin y$, $y \in [-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}]$. 2. Inverse cosine function: $y = \cos^{-1} x$ if and only if $x = \cos y$, $y \in [0, \pi]$. 3. Inverse tangent function: $y = \tan^{-1} x$ if and only if $x = \tan y$, $y \in (-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2})$. 4. Inverse cotangent function: $y = \cot^{-1} x$ if and only if $x = \cot y$, $y \in (0, \pi)$. 5. Inverse secant function: $y = \sec^{-1} x$ if and only if $x = \sec y$, $y \in [0, \frac{\pi}{2}) \cup (\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi]$. 6. Inverse cosecant function: $y = \csc^{-1} x$ if and only if $x = \csc y$, $y \in [-\frac{\pi}{2}, 0) \cup (0, \frac{\pi}{2}]$. 1.7.4 Hyperbolic Functions 1. Hyperbolic sine function: $\sinh x = \frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{2}$. 2. Hyperbolic cosine function: $\cosh x = \frac{e^x + e^{-x}}{2}$. 3. Hyperbolic tangent function: $\tanh x = \frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{e^x + e^{-x}}$. 4. Hyperbolic cotangent function: $\coth x = \frac{e^x + e^{-x}}{e^x - e^{-x}}$. 5. Hyperbolic secant function: $\text{sech } x = \frac{2}{e^x + e^{-x}}$. 6. Hyperbolic cosecant function: $\text{csch } x = \frac{2}{e^x - e^{-x}}$. Theorem 1.7.25 (Identities Involving Hyperbolic Functions): $\text{sech } x = \frac{1}{\cosh x}$, $\text{csch } x = \frac{1}{\sinh x}$, $\coth x = \frac{1}{\tanh x}$ $\tanh x = \frac{\sinh x}{\cosh x}$, $\coth x = \frac{\cosh x}{\sinh x}$ $\cosh x + \sinh x = e^x$ $\cosh x - \sinh x = e^{-x}$ $\cosh^2 x - \sinh^2 x = 1$ $1 - \tanh^2 x = \text{sech}^2 x$ $1 - \coth^2 x = -\text{csch}^2 x$ $\sinh(x \pm y) = \sinh x \cosh y \pm \cosh x \sinh y$ $\cosh(x \pm y) = \cosh x \cosh y \pm \sinh x \sinh y$ $\sinh 2x = 2 \sinh x \cosh x$ $\cosh 2x = \cosh^2 x + \sinh^2 x = 1 + 2 \sinh^2 x = 2 \cosh^2 x - 1$ 1.7.5 Inverse Hyperbolic Functions Theorem 1.7.27 (Inverse Hyperbolic Functions as Logarithms): $\sinh^{-1} x = \ln(x + \sqrt{x^2 + 1})$ for all $x \in \mathbb{R}$ $\cosh^{-1} x = \ln(x + \sqrt{x^2 - 1})$ for all $x \in [1, +\infty)$ $\tanh^{-1} x = \frac{1}{2} \ln(\frac{1+x}{1-x})$ for all $x \in (-1, 1)$ $\coth^{-1} x = \frac{1}{2} \ln(\frac{x+1}{x-1})$ for all $x \in (-\infty, -1) \cup (1, +\infty)$ $\text{sech}^{-1} x = \ln(\frac{1 + \sqrt{1-x^2}}{x})$ for all $x \in (0, 1]$ $\text{csch}^{-1} x = \ln(\frac{1}{x} + \frac{\sqrt{1+x^2}}{|x|})$ for all $x \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \{0\}$ 2 Derivatives and Differentiation 2.1 Slopes, the Derivative, and Basic Differentiation Rules Definition (Tangent Line): The slope $m_{TL}$ of the tangent line $l$ to the graph of $f$ at the point $P(x_0, f(x_0))$ is given by $m_{TL} = \lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \frac{f(x_0 + \Delta x) - f(x_0)}{\Delta x}$, provided this limit exists. The equation of the tangent line is $y - f(x_0) = m_{TL}(x - x_0)$. Definition (Normal Line): The normal line to the graph of $f$ at the point $P$ is the line perpendicular to the tangent line at $P$. 2.1.2 Definition of the Derivative Definition (Derivative): The derivative of a function $f(x)$, denoted $f'(x)$, is the function $f'(x) = \lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \frac{f(x + \Delta x) - f(x)}{\Delta x}$. It is defined at all points $x$ in the domain of $f$ where the limit exists. Remark 2.1.4: Hence, from the definition, $\text{dom } f' \subseteq \text{dom } f$ since there may be points $x_0 \in \text{dom } f$ at which $f'(x_0)$ does not exist. The definition also tells us that $f'(x_0)$ is the slope of the tangent line to the graph of the function at the point $P(x_0, f(x_0))$. To get the derivative of $f$ at $x \neq x_0$, we use $f'(x_0) = \lim_{x \to x_0} \frac{f(x) - f(x_0)}{x - x_0}$. Other notations: $y'$ if $y = f(x)$, $\frac{dy}{dx}$, $\frac{d}{dx}[f(x)]$, and $D_x[f(x)]$. The process of computing the derivative is called differentiation . 2.1.3 Differentiability Definition (Differentiability): A function $f$ is said to be differentiable at $x = x_0$ if the derivative $f'(x_0)$ exists. A function $f$ is differentiable on $(a, b)$ if $f$ is differentiable at every real number in $(a, b)$. A function $f$ is differentiable everywhere if it is differentiable at every real number. Remark: If $f(x)$ is a polynomial, a rational, or a trigonometric function, then $f(x)$ is differentiable on its domain. 2.1.4 Techniques of Differentiation Theorem 2.1.9 (Differentiation Rules): Let $f$ and $g$ be functions and $c \in \mathbb{R}$. If $f(x) = c \in \mathbb{R}$, then $f'(x) = 0$. (Power Rule) If $f(x) = x^n$, where $n \in \mathbb{Q}$, then $f'(x) = nx^{n-1}$. If $f(x) = c \cdot g(x)$, then $f'(x) = c \cdot g'(x)$ if $g'(x)$ exists. (Sum Rule) If $h(x) = f(x) + g(x)$, then $h'(x) = f'(x) + g'(x)$, provided both $f'(x)$ and $g'(x)$ exist. (Product Rule) If $h(x) = f(x)g(x)$, then $h'(x) = f'(x)g(x) + f(x)g'(x)$, provided $f'(x)$ and $g'(x)$ both exist. (Quotient Rule) If $h(x) = \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$ where $g(x) \neq 0$, then $h'(x) = \frac{g(x)f'(x) - f(x)g'(x)}{[g(x)]^2}$, provided $f'(x)$ and $g'(x)$ both exist. Theorem 2.1.12 (Derivatives of Trigonometric Functions): $D_x[\sin x] = \cos x$ $D_x[\cos x] = -\sin x$ $D_x[\tan x] = \sec^2 x$ $D_x[\cot x] = -\csc^2 x$ $D_x[\sec x] = \sec x \tan x$ $D_x[\csc x] = -\csc x \cot x$ Remark 2.1.13: The formulas in the previous theorem consider trigonometric functions as real-valued functions. Thus, whenever these formulas are applied to problems where trigonometric functions are viewed as functions on angles, the measure of an angle must be in radians. The derivative of a trigonometric function is either another trigonometric function or a product of trigonometric functions. That means that a trigonometric function is differentiable where its derivative is defined. Moreover, the domains of a trigonometric function and its derivative are the same. Hence, a trigonometric function is differentiable on its domain. 2.2 The Chain Rule, and more on Differentiability Theorem 2.2.1 (Chain Rule): If the function $g$ is differentiable at $x = x_0$ and the function $f$ is differentiable at $g(x_0)$, then $(f \circ g)(x)$ is differentiable at $x = x_0$ and $(f \circ g)'(x_0) = f'(g(x_0)) \cdot g'(x_0)$. Remark 2.2.2: The chain rule can also be stated in the following manner: If $y = f(u)$ and $u = g(x)$, then $\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{dy}{du} \frac{du}{dx}$ or $D_x[f(u)] = f'(u) D_x[u]$. The derivative of $f(g(x))$ is the derivative of the outside function evaluated at the inside function times the derivative of the inside function. 2.2.2 Derivatives from the Left and from the Right Definition (Derivative from the left): The derivative from the left of $f$ at $x = x_0$, denoted by $f'_-(x_0)$, is given by $f'_-(x_0) = \lim_{x \to x_0^-} \frac{f(x) - f(x_0)}{x - x_0}$. Definition (Derivative from the right): The derivative from the right of $f$ at $x = x_0$, denoted by $f'_+(x_0)$, is given by $f'_+(x_0) = \lim_{x \to x_0^+} \frac{f(x) - f(x_0)}{x - x_0}$. Remark 2.2.6: In Definition 2.2.2, it is necessary that the function $f$ is defined at $x_0$. Otherwise, the limit expressions do not make sense. The derivative from the left [right] is also referred to as the left-hand derivative [right-hand derivative], or simply left derivative [right derivative]. 2.2.3 Differentiability and Continuity Theorem 2.2.9: If $f$ is differentiable at $x = x_0$, then $f$ is continuous at $x = x_0$. Remark 2.2.10: If $f$ is discontinuous at $x = x_0$, then $f$ is not differentiable at $x = x_0$. If $f$ is continuous at $x = x_0$, it does not mean that $f$ is differentiable at $x = x_0$. If $f$ is not differentiable at $x = x_0$, it does not mean that $f$ is not continuous at $x = x_0$. Theorem 2.2.12: If $f$ is continuous at $x = x_0$ from the left and $\lim_{x \to x_0^-} f'(x)$ exists, then $f'_-(x_0) = \lim_{x \to x_0^-} f'(x)$. If $f$ is continuous at $x = x_0$ from the right and $\lim_{x \to x_0^+} f'(x)$ exists, then $f'_+(x_0) = \lim_{x \to x_0^+} f'(x)$. 2.2.4 Graphical Consequences of Differentiability and Non-differentiability Remark 2.2.15: A function $f$ is not differentiable at $x = x_0$ if one of the following is true: $f$ is discontinuous at $x = x_0$. The graph of $f$ has a vertical tangent line at $x = x_0$. The graph of $f$ has no well-defined tangent line at $x = x_0$, i.e., the graph of $f$ has a corner, edge or cusp at $x = x_0$. 2.2.5 Higher Order Derivatives Definition (Higher Order Derivatives): If the derivative $f'$ of a function $f$ is itself differentiable, then the derivative of $f'$ is called the second derivative of $f$ and is denoted $f''$. We can continue to obtain the third derivative, $f'''$, the fourth derivative, $f^{(4)}$, and even higher derivatives of $f$ as long as we have differentiability. The $n$-th derivative of the function $f$, denoted by $f^{(n)}$, is the derivative of the $(n-1)$-th derivative of $f$, that is, $f^{(n)}(x) = \lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \frac{f^{(n-1)}(x + \Delta x) - f^{(n-1)}(x)}{\Delta x}$. Remark 2.2.16: The $n$ in $f^{(n)}$ is called the order of the derivative. The derivative of a function $f$ is sometimes called the first derivative of $f$. The function $f$ is sometimes written as $f^{(0)}(x)$. Other notations: $D_x^n[f(x)]$, $\frac{d^ny}{dx^n}$, $\frac{d^n}{dx^n}[f(x)]$, and $y^{(n)}$. 2.2.6 Implicit Differentiation Implicit Differentiation Procedure: To obtain $\frac{dy}{dx}$ without solving for $y$ explicitly in terms of $x$, we use the method called implicit differentiation. To find $\frac{dy}{dx}$ using implicit differentiation, we: Think of the variable $y$ as a differentiable function of the variable $x$. Differentiate both sides of the equation, using the chain rule where necessary. Solve for $\frac{dy}{dx}$. 2.3 Derivatives of Exponential and Logarithmic Functions 2.3.1 Derivatives of Logarithmic Functions Derivatives of Logarithmic Functions: $D_x[\ln x] = \frac{1}{x}$ for all $x > 0$. $D_x[\log_a x] = \frac{1}{x \ln a}$ for all $x > 0$. $D_x[\ln |x|] = \frac{1}{x}$ for all $x \neq 0$. 2.3.2 Logarithmic Differentiation Logarithmic Differentiation Procedure: To differentiate an expression involving many products and quotients (or expressions of the form $f(x)^{g(x)}$): Take the absolute value of both sides of the equation and apply properties of the absolute value. Take the natural logarithm of both sides and apply properties of logarithms to obtain a sum. Take the derivative of both sides implicitly with respect to $x$ and solve for $\frac{dy}{dx}$. 2.3.3 Derivatives of Exponential Functions Theorem 2.3.4 (Derivatives of Exponential Functions): $D_x[a^x] = a^x \ln a$ ($a > 0$ and $a \neq 1$). $D_x[e^x] = e^x$. Theorem 2.3.6 (Power Rule for Real Exponents): If $f(x) = x^r$ where $r \in \mathbb{R}$, then $f'(x) = rx^{r-1}$. 2.3.4 Derivative of $f(x)^{g(x)}$ To differentiate expressions of the form $f(x)^{g(x)}$, we either use logarithmic differentiation or rewrite $f(x)^{g(x)}$ as $e^{g(x) \ln f(x)}$. 2.4 Derivatives of Other New Classes of Functions 2.4.1 Derivatives of Inverse Circular Functions Theorem 2.4.1 (Derivatives of Inverse Circular Functions): $D_x[\sin^{-1} x] = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}$ $D_x[\cos^{-1} x] = -\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}$ $D_x[\tan^{-1} x] = \frac{1}{1 + x^2}$ $D_x[\cot^{-1} x] = -\frac{1}{1 + x^2}$ $D_x[\sec^{-1} x] = \frac{1}{|x|\sqrt{x^2 - 1}}$ $D_x[\csc^{-1} x] = -\frac{1}{|x|\sqrt{x^2 - 1}}$ 2.4.2 Derivatives of Hyperbolic Functions Theorem 2.4.3 (Derivatives of Hyperbolic Functions): $D_x[\sinh x] = \cosh x$ $D_x[\cosh x] = \sinh x$ $D_x[\tanh x] = \text{sech}^2 x$ $D_x[\coth x] = -\text{csch}^2 x$ $D_x[\text{sech } x] = -\text{sech } x \tanh x$ $D_x[\text{csch } x] = -\text{csch } x \coth x$ 2.4.3 Derivatives of Inverse Hyperbolic Functions Theorem 2.4.5 (Derivatives of Inverse Hyperbolic Functions): $D_x[\sinh^{-1} x] = \frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2 + 1}}$ $D_x[\cosh^{-1} x] = \frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2 - 1}}$ ($x > 1$) $D_x[\tanh^{-1} x] = \frac{1}{1 - x^2}$ ($|x| $D_x[\coth^{-1} x] = \frac{1}{1 - x^2}$ ($|x| > 1$) $D_x[\text{sech}^{-1} x] = -\frac{1}{x\sqrt{1 - x^2}}$ ($0 $D_x[\text{csch}^{-1} x] = -\frac{1}{|x|\sqrt{x^2 + 1}}$ ($x \neq 0$) 2.5 The Mean Value Theorem 2.5.1 Rolle's Theorem Theorem 2.5.1 (Rolle's Theorem): Let $f$ be a function such that $f$ is continuous on the closed interval $[a, b]$, $f$ is differentiable on the open interval $(a, b)$, and $f(a) = f(b)$. Then there exists a number $c$ in the open interval $(a, b)$ such that $f'(c) = 0$. Remark 2.5.2: Note that condition (iii) of Rolle's Theorem implies that the line passing through the points $(a, f(a))$ and $(b, f(b))$ is horizontal. On the other hand, the conclusion implies that there is a horizontal tangent line to the graph of $f$ and the point of tangency has $x$-coordinate lying between $a$ and $b$. Continuity on $[a, b]$ is important because there are functions that satisfy only conditions (ii) and (iii) but do not satisfy the conclusion. It may also be the case that the conclusion is satisfied even if one of the premises is not satisfied. 2.5.2 The Mean Value Theorem Theorem 2.5.3 (The Mean Value Theorem): Let $f$ be a function such that $f$ is continuous on the closed interval $[a, b]$ and $f$ is differentiable on the open interval $(a, b)$. Then there is a number $c$ on the open interval $(a, b)$ such that $f'(c) = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a}$. Remark 2.5.4: The Mean Value Theorem is the generalization of Rolle's Theorem where the line $l$, passing through $(a, f(a))$ and $(b, f(b))$ is not necessarily horizontal. The conclusion says that there is a tangent line to the graph of $f$ that is parallel to $l$ and whose point of tangency has $x$-coordinate between $a$ and $b$. 2.6 Relative Extrema of a Function 2.6.1 Relative Extrema Definition (Relative Maximum): A function $f$ is said to have a relative maximum at $x = c$ if there is an open interval $I$ containing $c$ such that $f(x)$ is defined for all $x \in I$ and $f(x) \le f(c)$ for all $x \in I$. Definition (Relative Minimum): A function $f$ is said to have a relative minimum at $x = c$ if there is an open interval $I$ containing $c$ such that $f(x)$ is defined for all $x \in I$ and $f(x) \ge f(c)$ for all $x \in I$. Definition (Relative Extremum): We say $f$ has a relative extremum at $x = c$ if $f$ has either a relative maximum at $x = c$ or a relative minimum at $x = c$. Definition (Relative Extremum Point/Value): If $f$ has a relative extremum at $x = c$, then it is equivalent to saying that $(c, f(c))$ is a relative extremum point of $f$, or $f(c)$ is a relative extremum value of $f$. 2.6.2 Critical Numbers Definition (Critical Number): A number $c \in \text{dom } f$ is said to be a critical number of $f$ if either $f'(c) = 0$ or $f'(c)$ is undefined at $x = c$. Theorem 2.6.3: If $f$ has a relative extremum at $x = c$, then $c$ is a critical number of $f$. Remark 2.6.5: The preceding theorem says that relative extrema can only be attained at critical numbers of $f$, that is, if $c$ is not a critical number, then the point $(c, f(c))$ is not a relative extremum point of $f$. However, these critical numbers are only candidates for relative extrema. If $c$ is a critical number, $f$ may or may not have a relative extremum at $c$. 2.6.3 Increasing/Decreasing Functions Definition (Increasing Function): A function $f$ is said to be (strictly) increasing on $I$ if $f(a) Definition (Decreasing Function): A function $f$ is said to be (strictly) decreasing on $I$ if $f(a) > f(b)$ for all $a, b \in I$ such that $a Theorem 2.6.7 (Test for Increasing/Decreasing Functions): Let $f$ be a function that is continuous on the closed interval $[a, b]$ and differentiable on the open interval $(a, b)$. If $f'(x) > 0$ for all $x \in (a, b)$, then $f$ is increasing on $[a, b]$. If $f'(x) If $f'(x) = 0$ for all $x \in (a, b)$, then $f$ is constant on $[a, b]$. 2.6.4 The First Derivative Test for Relative Extrema Theorem 2.6.9 (First Derivative Test for Relative Extrema): Let $f$ be a function continuous on the open interval $(a, b)$ which contains the number $c$. Suppose that $f$ is also differentiable on the open interval $(a, b)$, except possibly at $c$. If $f'(x) > 0$ for all $x \in (a, c)$ and $f'(x) If $f'(x) 0$ for all $x \in (c, b)$, then $f$ has a relative minimum at $x = c$. If $f'(x)$ does not change signs from $(a, c)$ to $(c, b)$, then there is no relative extremum at $x = c$. 2.7 Concavity and the Second Derivative Test 2.7.1 Concavity Definition (Concave Up at a Point): The graph of a function $f$ is said to be concave up at the point $P(c, f(c))$ if $f'(c)$ exists and there is an open interval $I$ containing $c$ such that for all $x \in I \setminus \{c\}$, the point $(x, f(x))$ is above the tangent line to the graph of $f$ at $P$. Definition (Concave Up on an Interval): We say that the graph of $f$ is concave up on an interval $I$ if it is concave up at $(c, f(c))$ for all $c \in I$. Definition (Concave Down at a Point): The graph of a function $f$ is said to be concave down at the point $P(c, f(c))$ if $f'(c)$ exists and there is an open interval $I$ containing $c$ such that for all $x \in I \setminus \{c\}$, the point $(x, f(x))$ is below the tangent line to the graph of $f$ at $P$. Definition (Concave Down on an Interval): We say that the graph of $f$ is concave down on an interval $I$ if it is concave down at $(c, f(c))$ for all $c \in I$. Theorem 2.7.2 (Test for Concavity): Let $f$ be a function such that $f''$ exists on $(a, b)$. If $f''(x) > 0$ for all $x \in (a, b)$, then the graph of $f$ is concave up on $(a, b)$. If $f''(x) 2.7.2 Point of Inflection Definition (Point of Inflection): The graph of $f(x)$ has a point of inflection at $P(c, f(c))$ if $f$ is continuous at $x = c$ and the graph of $f$ changes concavity at $P$, i.e. there is an open interval $(a, b)$ containing $c$ such that $f''(x) > 0$ for all $x \in (a, c)$ and $f''(x) $f''(x) 0$ for all $x \in (c, b)$. Theorem 2.7.4: If $P(c, f(c))$ is a point of inflection of the graph of the function $f$, then $f''(c) = 0$ or $f''(c)$ does not exist. Remark 2.7.6: The converse of the preceding theorem is not true. That is, if $f''(c) = 0$ or $f''(c)$ dne, the graph of $f$ may or may not have a point of inflection at $x = c$. Definition (Possible Point of Inflection): A number $c \in \text{dom } f$ is said to be a possible point of inflection of $f$ if either $f''(x) = 0$ or $f''(x)$ does not exist at $x = c$. 2.7.3 The Second Derivative Test for Relative Extrema Theorem 2.7.8 (Second Derivative Test for Relative Extrema): Let $f$ be a function such that $f'$ and $f''$ exist for all values of $x$ on some open interval containing $x = c$ and $f'(c) = 0$. If $f''(c) If $f''(c) > 0$, then $f$ has a relative minimum value at $x = c$. If $f''(c) = 0$, we have no conclusion ($f$ may or may not have a relative extremum at $x = c$). Remark 2.7.9: Note that the second derivative test is only applicable to the first type of critical numbers: those that make the first derivative zero ($x$-coordinates of so-called stationary points). 2.8 Graph Sketching Guidelines for Graphing a Function $f$ Analytically: Find the domain and intercepts of $f$. Determine vertical, horizontal, and oblique asymptotes of $f$ by computing necessary limits. Compute $f'$ and $f''$. Determine the critical numbers and possible points of inflection, if any. Construct a table of signs with intervals divided at the numbers that make $f'$ zero or undefined, and $f''$ zero or undefined. Indicate the sign of $f'$ and $f''$ on each interval. Determine the intervals on which $f$ is increasing or decreasing and where it is concave up or concave down. Determine the coordinates of the relative extremum points and points of inflection, if any. Plot important points (intercepts, holes, relative extremum points, points of inflection) and asymptotes first. Use the table of signs of $f'$ and $f''$ to graph the rest of the function. 3.1 Absolute Extrema of a Function on an Interval Definition (Absolute Maximum): A function $f$ is said to have an absolute maximum value on an interval $I$ at $x_0$ if $f(x_0) \ge f(x)$ for any $x \in I$. Definition (Absolute Minimum): Similarly, $f$ is said to have an absolute minimum value on an interval $I$ at $x_0$ if $f(x_0) \le f(x)$ for any $x \in I$. Definition (Absolute Extremum): If $f$ has either an absolute maximum or absolute minimum value on $I$ at $x_0$, then we say $f$ has an absolute extremum on $I$ at $x_0$. Remarks: Unlike with relative extrema, the interval $I$ need not be an open interval. Note that the absolute maximum (or minimum) value of a function on an interval is unique, if it exists. However, the graph of $f$ may have more than one absolute maximum (or minimum) point (same $y$-values but different $x$-values). Theorem 3.1.2 (Extreme Value Theorem): If $f$ is continuous on $[a, b]$, then $f$ has both an absolute maximum and an absolute minimum on $[a, b]$. Remark 3.1.3: If you replace $[a, b]$ by one of the following intervals $(a, b)$, $[a, b)$, $(a, b]$, $(a, +\infty)$, $(-\infty, b)$, $[a, +\infty)$, $(-\infty, b]$, then the conclusion of the Extreme Value Theorem does not follow. Theorem 3.1.4: If $f$ has an absolute extremum on the open interval $(a, b)$ at $x = c$, then $c$ is a critical number of $f$ on $(a, b)$, that is, either $f'(c) = 0$ or $f'(c)$ is undefined. Finding absolute extrema of $f$ on $[a, b]$: Find critical numbers of $f$ between $a$ and $b$, say $c_1, \dots, c_m$. Evaluate $f$ at each critical number and at the endpoints $a$ and $b$. Compare $f(c_1), \dots, f(c_m), f(a)$ and $f(b)$. The number that gives the highest (lowest) value of $f$ gives the absolute maximum (minimum). Theorem 3.1.6: Suppose the function $f$ is continuous on an interval $I$ containing $x_0$, and $x_0$ is the only number in $I$ for which $f$ has a relative extremum. If $f$ has a relative maximum at $x_0$, then $f$ has an absolute maximum on $I$ at $x_0$. If $f$ has a relative minimum at $x_0$, then $f$ has an absolute minimum on $I$ at $x_0$. 3.1.3 Optimization: Application of Absolute Extrema on Word Problems Suggestions on Solving Optimization Problems: If possible, draw a diagram of the problem corresponding to a general situation. Assign variables to all quantities involved. Identify the objective function. Identify the quantity, say $q$, to be maximized or minimized. Formulate an equation involving $q$ and other quantities. Express $q$ in terms of a single variable, say $x$. If necessary, use the given information and relationships between quantities to eliminate some variables. The objective function to be maximized/minimized is $q = f(x)$. Determine the domain or constraint of $q$ from the physical restrictions of the problem. Use appropriate theorems involving absolute extrema to solve the problem. Make sure to give the exact answer to the question with the correct units of measurement. 3.2 Rates of Change, Rectilinear Motion, and Related Rates 3.2.1 Rates of Change Average Rate of Change: The average rate of change of $y$ with respect to $x$ on $[x_0, x]$ is $\frac{\Delta f}{\Delta x} = \frac{f(x) - f(x_0)}{x - x_0}$. Instantaneous Rate of Change: The instantaneous rate of change of $y$ with respect to $x$ at $x = x_0$ is $\lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \frac{\Delta f}{\Delta x} = \lim_{x \to x_0} \frac{f(x) - f(x_0)}{x - x_0} = f'(x_0)$. Rate of Change of $y$ with respect to $x$: If $\frac{dy}{dx} > 0$ on an interval $I$, then $y$ increases as $x$ increases, and $y$ decreases as $x$ decreases. If $\frac{dy}{dx} If $\frac{dy}{dx} = 0$ on an interval $I$, then $y$ does not change with respect to $x$. 3.2.2 Rectilinear Motion Position Function: Suppose a particle is moving along a horizontal line, which we shall refer to as the $s$-axis. Suppose the position of the particle at time $t$ is given by the function $s(t)$, called the position function of the particle. Average Velocity: The average velocity of the particle on $[t_0, t]$ is $v_{ave} = \frac{s(t) - s(t_0)}{t - t_0}$. Instantaneous Velocity: The instantaneous velocity of the particle at time $t$ is $v(t) = \lim_{\Delta t \to 0} \frac{\Delta s}{\Delta t} = \frac{ds}{dt} = s'(t)$. Instantaneous Speed: The instantaneous speed of the particle at time $t$ is $|v(t)|$. Instantaneous Acceleration: The instantaneous acceleration of the particle at time $t$ is $a(t) = \frac{dv}{dt} = v'(t)$ or $a(t) = \frac{d^2s}{dt^2} = s''(t)$. Remark 3.2.5 (Interpretation of Motion): Let $s(t)$ be the position function of a particle moving along the $s$-axis. Note that $\Delta t$ is always positive. The signs of $v(t)$ and $a(t)$ give us information about the motion of the particle. If $v(t) > 0$, then the particle is moving in the positive direction of $s$ (usually to the right or upward) at time $t$. If $v(t) If $v(t) = 0$, either the particle is not moving or is changing direction at time $t$. If $a(t) > 0$, then the velocity of the particle is increasing at time $t$. In addition, if $v(t) > 0$, then the speed of the particle is increasing at time $t$ (speeding up). if $v(t) If $a(t) if $v(t) > 0$, then the speed of the particle is decreasing at time $t$. if $v(t) If $a(t) = 0$, then the velocity of the particle is constant. 3.2.3 Related Rates Related Rates: Let $x$ be a quantity that is a function of time $t$, meaning the quantity changes over time. Then $\frac{dx}{dt}$ is the rate of change of $x$ with respect to $t$. A problem on related rates is a problem involving rates of change of several variables where one variable is dependent on another. In particular, if $y$ is dependent on $x$, then the rate of change of $y$ with respect to $t$ is dependent on the rate of change of $x$ with respect to $t$, that is, $\frac{dy}{dt}$ is dependent on $\frac{dx}{dt}$. Suggestions in solving problems involving related rates: Let $t$ denote the elapsed time. If possible, draw a diagram of the problem that is valid for any time $t > 0$. Select variables to represent the quantities that change with respect to time. Label those quantities whose values do not depend on $t$ with their given constant values. Write down any numerical facts known about the variables. Interpret each rate of change as the derivative of a variable with respect to time. Remember that if a quantity decreases over time, then its rate of change is negative. Identify what is being asked. Write an equation relating the variables that is valid for any time $t > 0$. Differentiate the equation in (5) implicitly with respect to $t$. Substitute in the equation obtained in (6) all values that are valid at the particular time of interest. Solve for what is being asked. Write a conclusion that answers the question in the problem. Do not forget to include the correct units of measurement. 3.3 Local Linear Approximation, Differentials, and Marginals 3.3.1 Differentials Definition (Differential $dx$): The differential $dx$ of the independent variable $x$ denotes an arbitrary increment of $x$. Definition (Differential $dy$): The differential $dy$ of the dependent variable $y$ associated with $x$ is given by $dy = f'(x)dx$. Remark 3.3.1: Symbolically, we may interpret $\frac{dy}{dx}$ as either the derivative of $y = f(x)$ with respect to $x$ or the quotient of the differential of $y$ by the differential of $x$. Other interpretation of this quantity: The value of $dx$ is equal to $\Delta x$, an increment of $x$. If $\Delta x$ is small enough, the value of $dy$ is approximately equal to the actual change in function value, $\Delta y$. If $\Delta x$ is small enough, the value of $\frac{dy}{dx}$ approximates the slope of the secant line through the points $P(x_0, f(x_0))$ and $Q(x, f(x))$. Remark 3.3.2: Let $u$ be a function of $x$ and $c$ be a constant. If $u = c$, then $du = 0$. If $u = x^m$, then $du = mx^{m-1}dx$. If $u = cx$, then $du = cdx$. Local Linear Approximation: $f(x) \approx f(x_0) + f'(x_0)(x - x_0)$. If $dx = \Delta x = x - x_0$, then $x = x_0 + dx$. Since $f(x) \approx f(x_0) + f'(x_0)(x - x_0)$, we have $f(x_0 + dx) \approx f(x_0) + f'(x_0)dx$. Approximation with Differentials: If $dx \approx 0$, then $dy = f'(x)dx = f'(x)\Delta x \approx \Delta y$. Hence, for sufficiently small values of $dx$, $dy \approx \Delta y$. 3.3.3 Marginals Marginal Profit: $\frac{dP}{dx}$ Marginal Revenue: $\frac{dR}{dx}$ Marginal Cost: $\frac{dC}{dx}$ Remark 3.3.6: Cost function $C(x)$ - cost of producing $x$ units of a product. Revenue function $R(x)$ - revenue in the sale of $x$ units of a product. Profit function $P(x)$ - profit earned in the sale of $x$ units of a product. Price-demand function $p(x)$ - price of product if there are $x$ demands. The revenue and price-demand functions are related by the equation $R(x) = x \cdot p(x)$. The profit, revenue and cost functions are related by the equation $P(x) = R(x) - C(x) = x \cdot p(x) - C(x)$. $C(x) \ge 0$ and $C(0)$ is the overhead or fixed cost. $R(x) \ge 0$ and $R(0) = 0$. $P(x)$ may be positive, negative or zero. The marginal function value at a number $n$ is the rate of change of the function when $x = n$. This value is an approximation of $F(n+1) - F(n)$, where $F = C, R \text{ or } P$. 3.4 Indeterminate Forms and L'Hôpital's Rule 3.4.1 Indeterminate Forms of Type $\frac{0}{0}$ and $\frac{\infty}{\infty}$ Theorem 3.4.2 (L'Hôpital's Rule): Let $f$ and $g$ be functions differentiable on an open interval $I$ containing $a$ except possibly at $a$ and $g'(x) \neq 0$ for all $x \in I \setminus \{a\}$. If $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$ is indeterminate of type $\frac{0}{0}$ or $\frac{\infty}{\infty}$, then $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \lim_{x \to a} \frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)}$, provided that $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)}$ exists or is $\pm\infty$. Remark 3.4.3: L'Hôpital's Rule, with suitable modifications, is valid if "$x \to a$" is replaced by "$x \to a^-$", "$x \to a^+$", "$x \to +\infty$" or "$x \to -\infty$". 3.4.3 Indeterminate Forms of Type $0 \cdot \infty$ and $\infty - \infty$ Indeterminate Form of Type $0 \cdot \infty$: The limit $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)g(x)$ is an indeterminate form of type $0 \cdot \infty$ if either $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = 0$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = \pm\infty$, or $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = \pm\infty$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = 0$. Indeterminate Form of Type $\infty - \infty$: The limit $\lim_{x \to a} (f(x) + g(x))$ is an indeterminate form of type $\infty - \infty$ if either $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = +\infty$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = -\infty$, or $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = -\infty$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = +\infty$. Remark 3.4.6: L'Hôpital's Rule works only for indeterminate forms of type $\frac{0}{0}$ and $\frac{\infty}{\infty}$. Any other indeterminate form must be expressed equivalently in one of these two forms if we wish to apply L'Hôpital's Rule. For the new indeterminate forms described above, these conversions can be performed as described below. If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = 0$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = \pm\infty$, write $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)g(x)$ as: $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{1/g(x)}$, which is indeterminate of type $\frac{0}{0}$, or $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{g(x)}{1/f(x)}$, which is indeterminate of type $\frac{\infty}{\infty}$, and apply L'Hôpital's Rule. If $\lim_{x \to a} (f(x) + g(x))$ is indeterminate of type $\infty - \infty$, rewrite $f(x) + g(x)$ as a single expression to obtain an indeterminate form of type $\frac{0}{0}$ or $\frac{\infty}{\infty}$ and apply L'Hôpital's Rule. 3.4.4 Indeterminate Forms of Type $1^{\infty}$, $0^0$ and $\infty^0$ Indeterminate Forms of Exponential Type: Let $f$ be a nonconstant function. The $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)^{g(x)}$ is an indeterminate form of type: $1^{\infty}$ if $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = 1$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = \pm\infty$. $0^0$ if $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = 0$, through positive values, and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = 0$. $\infty^0$ if $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = +\infty$ and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = 0$. Remark 3.4.8: If $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)^{g(x)}$ is indeterminate of type $1^{\infty}$, $0^0$ or $\infty^0$, we write $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)^{g(x)} = \lim_{x \to a} e^{g(x) \ln[f(x)]}$ and evaluate $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) \ln[f(x)]$ first. Then, if $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) \ln[f(x)] = L \in \mathbb{R}$, then $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)^{g(x)} = e^L$. $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) \ln[f(x)] = +\infty$, then $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)^{g(x)} = +\infty$. $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) \ln[f(x)] = -\infty$, then $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)^{g(x)} = 0$. 4 Integration and Its Applications 4.1 Antidifferentiation and Indefinite Integrals Definition (Antiderivative): A function $F$ is an antiderivative of the function $f$ on an interval $I$ if $F'(x) = f(x)$ for every value of $x$ in $I$. Remark 4.1.2: If an antiderivative of $f$ exists, then it is not unique. Theorem 4.1.3: If $F$ is an antiderivative of $f$ on an interval $I$, then every antiderivative of $f$ on $I$ is given by $F(x) + C$, where $C$ is an arbitrary constant. Remark 4.1.4: By the theorem above, we can conclude that if $F_1$ and $F_2$ are antiderivatives of $f$, then $F_2(x) = F_1(x) + C$. That is, $F_2$ and $F_1$ differ only by a constant. Terms and Notations: Antidifferentiation is the process of finding antiderivatives. If $F$ is an antiderivative of $f$, we write $\int f(x)dx = F(x) + C$. The symbol $\int$ (called the integral sign), denotes the operation of antidifferentiation. The function $f$ is called the integrand . The expression $F(x)+C$ is called the general antiderivative of $f$. Meanwhile, each antiderivative of $f$ is called a particular antiderivative of $f$. Theorem 4.1.6 (Theorems on Antidifferentiation): $\int c dx = cx + C$ If $a$ is a constant, then $\int af(x) dx = a \int f(x)dx$. If $f$ and $g$ are defined on the same interval, then $\int [f(x) \pm g(x)] dx = \int f(x)dx \pm \int g(x)dx$. If $n$ is any real number and $n \neq -1$, then $\int x^n dx = \frac{x^{n+1}}{n+1} + C$. Theorem 4.1.8 (Antiderivatives of Trigonometric Functions): $\int \sin x dx = -\cos x + C$ $\int \cos x dx = \sin x + C$ $\int \sec^2 x dx = \tan x + C$ $\int \csc^2 x dx = -\cot x + C$ $\int \sec x \tan x dx = \sec x + C$ $\int \csc x \cot x dx = -\csc x + C$ 4.1.2 Particular Antiderivatives A particular antiderivative of $f(x)$ is found by satisfying a given condition, called an initial or boundary condition . 4.1.3 Integration by Substitution Theorem 4.1.11 (Substitution Rule): If $u = g(x)$ is a differentiable function whose range is an interval $I$ and $f$ is continuous on $I$, then $\int f(g(x)) \cdot g'(x)dx = \int f(u) du$. 4.1.4 Rectilinear Motion Revisited Recall that $v(t) = s'(t)$ and $a(t) = v'(t)$. Therefore, $s(t)$ is a particular antiderivative of $v(t)$ while $v(t)$ is a particular antiderivative of $a(t)$. 4.1.5 Antiderivatives of $\frac{1}{x}$ and of the other Circular Functions Theorem 4.1.14: $\int \frac{1}{u} du = \ln|u| + C$. Theorem 4.1.16 (Antiderivatives of Trigonometric Functions involving $\ln$): $\int \tan x dx = \ln|\sec x| + C$ $\int \cot x dx = \ln|\sin x| + C$ $\int \sec x dx = \ln|\sec x + \tan x| + C$ $\int \csc x dx = \ln|\csc x - \cot x| + C$ 4.1.6 Antiderivatives of Exponential Functions Theorem 4.1.18 (Antiderivatives of Exponential Functions): $\int a^x dx = \frac{a^x}{\ln a} + C$ ($a > 0$ and $a \neq 1$) $\int e^x dx = e^x + C$ 4.1.7 Antiderivatives Yielding the Inverse Circular Functions Theorem 4.1.20 (Antiderivatives Yielding the Inverse Circular Functions): $\int \frac{dx}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}} = \sin^{-1} x + C$ $\int \frac{dx}{1 + x^2} = \tan^{-1} x + C$ $\int \frac{dx}{x\sqrt{x^2 - 1}} = \sec^{-1} x + C$ Theorem 4.1.21 (Generalized Inverse Circular Functions): Let $a > 0$. $\int \frac{du}{\sqrt{a^2 - u^2}} = \sin^{-1} \left(\frac{u}{a}\right) + C$ $\int \frac{du}{a^2 + u^2} = \frac{1}{a} \tan^{-1} \left(\frac{u}{a}\right) + C$ $\int \frac{du}{u\sqrt{u^2 - a^2}} = \frac{1}{a} \sec^{-1} \left(\frac{u}{a}\right) + C$ 4.1.8 Antiderivatives of Hyperbolic Functions Theorem 4.1.23 (Antiderivatives of Hyperbolic Functions): $\int \cosh x dx = \sinh x + C$ $\int \sinh x dx = \cosh x + C$ $\int \text{sech}^2 x dx = \tanh x + C$ $\int \text{csch}^2 x dx = -\coth x + C$ $\int \text{sech } x \tanh x dx = -\text{sech } x + C$ $\int \text{csch } x \coth x dx = -\text{csch } x + C$ $\int \tanh x dx = \ln(\cosh x) + C$ $\int \coth x dx = \ln|\sinh x| + C$ $\int \text{sech } x dx = 2 \tan^{-1}(e^x) + C = \tan^{-1}(\sinh x) + C$ $\int \text{csch } x dx = \ln|\tanh(x/2)| + C$ 4.1.9 Antiderivatives Yielding Inverse Hyperbolic Functions Theorem 4.1.25 (Antiderivatives Yielding the Inverse Hyperbolic Functions): Let $a > 0$. $\int \frac{du}{\sqrt{u^2 + a^2}} = \sinh^{-1} \left(\frac{u}{a}\right) + C = \ln(u + \sqrt{u^2 + a^2}) + C$ $\int \frac{du}{\sqrt{u^2 - a^2}} = \cosh^{-1} \left(\frac{u}{a}\right) + C = \ln(u + \sqrt{u^2 - a^2}) + C$, $u > a$ $\int \frac{du}{a^2 - u^2} = \frac{1}{a} \tanh^{-1} \left(\frac{u}{a}\right) + C = \frac{1}{2a} \ln\left(\frac{a+u}{a-u}\right) + C$, if $|u| $\int \frac{du}{a^2 - u^2} = \frac{1}{a} \coth^{-1} \left(\frac{u}{a}\right) + C = \frac{1}{2a} \ln\left(\frac{u+a}{u-a}\right) + C$, if $|u| > a$ $\int \frac{du}{u\sqrt{a^2 - u^2}} = -\frac{1}{a} \text{sech}^{-1} \left(\frac{u}{a}\right) + C = -\frac{1}{a} \ln\left(\frac{a + \sqrt{a^2 - u^2}}{u}\right) + C$, if $0 $\int \frac{du}{u\sqrt{a^2 + u^2}} = -\frac{1}{a} \text{csch}^{-1} \left(\frac{u}{a}\right) + C = -\frac{1}{a} \ln\left(\frac{a + \sqrt{a^2 + u^2}}{u}\right) + C$, if $u \neq 0$ 4.2 The Definite Integral 4.2.1 Area of a Plane Region: The Rectangle Method Definition (Sigma Notation): Let $n$ be a positive integer, and $F$ be a function such that $\{1, 2, \dots, n\}$ is in the domain of $F$. We define $\sum_{i=1}^n F(i) := F(1) + F(2) + \dots + F(n)$. Theorem 4.2.3 (Properties of Summation): Let $n$ be a positive integer, $c$ be a real number, and $F$ and $G$ be functions defined on the set $\{1, 2, \dots, n\}$. $\sum_{i=1}^n c = cn$ $\sum_{i=1}^n cF(i) = c \sum_{i=1}^n F(i)$ $\sum_{i=1}^n [F(i) \pm G(i)] = \sum_{i=1}^n F(i) \pm \sum_{i=1}^n G(i)$ $\sum_{i=1}^n i = \frac{n(n+1)}{2}$ $\sum_{i=1}^n i^2 = \frac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{6}$ $\sum_{i=1}^n i^3 = \left(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right)^2$ Area of a Plane Region: If $f(x) \ge 0$ on $[a,b]$, the area of the region bounded by $y=f(x)$, the $x$-axis, and the vertical lines $x=a$ and $x=b$ is approximated by $A_R \approx \sum_{i=1}^n f(c_i) \Delta x$. 4.2.2 The Definite Integral Definition (Definite Integral): Let $f$ be defined on $[a, b]$. The definite integral of $f$ from $a$ to $b$ is $\int_a^b f(x)dx = \lim_{\text{max }\Delta x_i \to 0} \sum_{i=1}^n f(x_i^*) \Delta x_i$, if the limit exists and does not depend on the choice of partitions or on the choice of numbers $x_i^*$ in the subintervals. If the limit exists, the function is said to be integrable on $[a, b]$. Terminologies and Notations: The process of calculating the integral is called integration . The integral sign $\int$ resembles the letter S because an integral is the limit of a sum. The function $f(x)$ is called the integrand . The numbers $a$ and $b$ are called the limits of integration : $a$ is the lower limit of integration, while $b$ is the upper limit of integration. We use the same symbol as the antiderivative because the definite integral is closely linked to the antiderivative. Remark 4.2.6: The definite integral is a number which does not depend on the variable used. The value of the definite integral does not change if $x$ is replaced by any other variable. For example, $\int_a^b f(x)dx = \int_a^b f(t)dt$. Geometrically, the definite integral $\int_a^b f(x)dx$ gives the net-signed area between the graph of the curve $y = f(x)$ and the interval $[a, b]$. In particular, if the graph of $y = f(x)$ lies above the $x$-axis in the interval $[a, b]$, $\int_a^b f(x)dx$ gives the area of the region bounded by the curve $y = f(x)$, the $x$-axis, and the lines $x = a$ and $x = b$. Theorem 4.2.8: If a function is continuous on $[a, b]$, then it is integrable on $[a, b]$. Theorem 4.2.10 (Properties of the Definite Integral): Let $f$ and $g$ be integrable on $[a, b]$. $\int_a^b f(x)dx = -\int_b^a f(x)dx$ $\int_a^a f(x)dx = 0$ $\int_a^b c dx = c(b - a)$ $\int_a^b cf(x)dx = c\int_a^b f(x)dx$ $\int_a^b [f(x) \pm g(x)] dx = \int_a^b f(x)dx \pm \int_a^b g(x)dx$ If $f$ is integrable on a closed interval $I$ containing the three numbers $a, b$ and $c$, $\int_a^b f(x)dx = \int_a^c f(x)dx + \int_c^b f(x)dx$ regardless of the order of $a, b$ and $c$. 4.3 The Fundamental Theorem of the Calculus 4.3.1 First Fundamental Theorem of the Calculus Theorem 4.3.2 (The First Fundamental Theorem of Calculus): Let $f$ be a function continuous on $[a, b]$ and let $x$ be any number in $[a, b]$. If $F$ is the function defined by $F(x) = \int_a^x f(t)dt$, then $F'(x) = f(x)$. Remark 4.3.4: Suppose $F(x) = \int_a^{g(x)} f(t)dt$, where $f$ is a function continuous on $[a, b]$ and let $g(x) \in [a, b]$. If we let $H(x) = \int_a^x f(t)dt$, then $F(x) = H(g(x))$. Using the chain rule, we get $F'(x) = H'(g(x)) g'(x)$. By the First Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, $H'(x) = f(x)$. So, we have $F'(x) = f(g(x)) \cdot g'(x)$. 4.3.2 Second Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Theorem 4.3.6 (The Second Fundamental Theorem of Calculus): Let $f$ be a function continuous on $[a, b]$. If $F$ is any antiderivative of $f$ on $[a, b]$, then $\int_a^b f(x)dx = F(x)|_a^b = F(b) - F(a)$. Remark 4.3.8: By the Second Fundamental Theorem of Calculus and the Substitution Rule, $\int_a^b f(g(x))g'(x)dx = F(g(x))|_a^b = F(g(b)) - F(g(a))$. If we let $u = g(x)$, we have that $\int_a^b f(g(x))g'(x)dx = \int_{g(a)}^{g(b)} f(u)du$. Remark 4.3.10: The Fundamental Theorems of Calculus establish a close connection between antiderivatives and definite integrals. For this reason, $\int f(x)dx$ is also referred to as an indefinite integral , and the process of antidifferentiation as integration . To use the Second Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, the function $f$ must be continuous on $[a, b]$. 4.4 Generalization of the Area of a Plane Region Formula for the Area of a Plane Region (Vertical Approach): If $f$ and $g$ are continuous functions on the interval $[a, b]$ and $f(x) \ge g(x)$ for all $x \in [a, b]$, then the area of the region $R$ bounded above by $y = f(x)$, below by $y = g(x)$, and the vertical lines $x = a$ and $x = b$ is $A_R = \int_a^b (f(x) - g(x))dx$. Formula for the Area of a Plane Region (Horizontal Approach): If $u$ and $v$ are continuous functions in $y$ on the interval $[c, d]$ and $v(y) \ge u(y)$ for all $y \in [c, d]$, then the area of the region $R$ bounded on the left by $x = u(y)$, on the right by $x = v(y)$ and the horizontal lines $y = c$ and $y = d$ is $A_R = \int_c^d (v(y) - u(y))dy$. 4.5 Arc Length of Plane Curves Formula for the Length of an Arc: If $y = f(x)$ is a smooth curve on the interval $[a, b]$, then the arc length $L$ of this curve from $x = a$ to $x = b$ is $L = \int_a^b \sqrt{1 + \left(\frac{dy}{dx}\right)^2} dx = \int_a^b \sqrt{1 + [f'(x)]^2} dx$. If $x = u(y)$ is a smooth curve on the interval $[c, d]$, then the arc length $L$ of this curve from $y = c$ to $y = d$ is $L = \int_c^d \sqrt{1 + \left(\frac{dx}{dy}\right)^2} dy = \int_c^d \sqrt{1 + [u'(y)]^2} dy$. Remark 4.5.2: Note in the previous example that our expression for the perimeter involves $x$ and $y$. This is sometimes the case, especially for the perimeter of regions with varying boundaries. The thing to take away here is that each integral must contain only one variable of integration; that is, $x$ and $y$ cannot appear in a single integrand. 4.6 Volumes of Solids 4.6.1 Volumes of Solids of Revolution Definition (Solid of Revolution): A solid of revolution is a solid obtained when a plane region is revolved about a line called the axis of revolution . Remark 4.6.2 (Methods for Volume): Two methods allow us to find the volume of a solid of revolution: Disk or Washer Method: Use rectangles that are perpendicular to the axis of revolution. Cylindrical Shell Method: Use rectangles that are parallel to the axis of revolution. Distance from an arbitrary point to the axis of revolution: If the axis of revolution is a vertical line, the horizontal distance from the axis of revolution to an arbitrary point on the curve is given by $d = (x\text{-coordinate of the right curve}) - (x\text{-coordinate of the left curve})$. If the axis of revolution is a horizontal line, the vertical distance from the axis of revolution to an arbitrary point on the curve is given by $d = (y\text{-coordinate of the upper curve}) - (y\text{-coordinate of the lower curve})$. Formula for the Volume of a Solid of Revolution using Disks or Washers (Vertical Rectangles): Suppose $R$ is the region bounded above by $y = f(x)$, below by $y = g(x)$, and the vertical lines $x = a$ and $x = b$ such that $f$ and $g$ are continuous functions on $[a, b]$. If the line $y = y_0$ does not intersect the interior of $R$, then the volume of the solid of revolution obtained when $R$ is revolved about the line $y = y_0$ is given by: If only disks are obtained (that is, a boundary of $R$ lies on the axis of revolution), then $V = \int_a^b \pi [r(x)]^2 dx$, where $r(x)$ is the radius of a disk at an arbitrary $x$ in $[a, b]$. If washers are obtained (that is, a boundary of $R$ does not lie on the axis of revolution), then $V = \int_a^b \pi ([r_2(x)]^2 - [r_1(x)]^2) dx$, where $r_2(x)$ and $r_1(x)$ are the outer radius and inner radius, respectively, of a washer at an arbitrary $x$ in $[a, b]$. Formula for the Volume of a Solid of Revolution using Disks or Washers (Horizontal Rectangles): Suppose $R$ is the region bounded on the left by $x = u(y)$, on the right by $x = v(y)$ and the horizontal lines $y = c$ and $y = d$ such that $u$ and $v$ are continuous functions on $[c, d]$. If the line $x = x_0$ does not intersect the interior of $R$, then the volume of the solid of revolution obtained when $R$ is revolved about the line $x = x_0$ is given by: If only disks are obtained, then $V = \int_c^d \pi [r(y)]^2 dy$, where $r(y)$ is the radius of a disk at an arbitrary $y$ in $[c, d]$. If washers are obtained, then $V = \int_c^d \pi ([r_2(y)]^2 - [r_1(y)]^2) dy$, where $r_2(y)$ and $r_1(y)$ are the outer radius and inner radius, respectively, of a washer at an arbitrary $y$ in $[c, d]$. Formula for the Volume of a Solid of Revolution using Cylindrical Shells (Vertical Rectangles): Suppose $R$ is the region bounded above by $y = f(x)$, below by $y = g(x)$, and the vertical lines $x = a$ and $x = b$ such that $f$ and $g$ are continuous functions on $[a, b]$. If the line $x = x_0$ does not intersect the interior of $R$, then the volume of the solid of revolution obtained when $R$ is revolved about the line $x = x_0$ is given by $V = \int_a^b 2\pi r(x)h(x)dx$, where $r(x)$ and $h(x)$ are the radius and height, respectively, of a cylindrical shell at an arbitrary $x$ in $[a, b]$. Formula for the Volume of a Solid of Revolution using Cylindrical Shells (Horizontal Rectangles): Suppose $R$ is the region bounded on the left by $x = u(y)$, on the right by $x = v(y)$ and the horizontal lines $y = c$ and $y = d$ such that $u$ and $v$ are continuous functions on $[c, d]$. If the line $y = y_0$ does not intersect the interior of $R$, then the volume of the solid of revolution obtained when $R$ is revolved about the line $y = y_0$ is given by $V = \int_c^d 2\pi r(y)h(y)dy$, where $r(y)$ and $h(y)$ are the radius and height, respectively, of a cylindrical shell at an arbitrary $y$ in $[c, d]$. 4.6.2 Volume of Solids by Slicing Volume of a cylinder: Area of a cross-section $\times$ Height. Formula for the Volume of a Solid by Slicing (Vertical Cylinders): Let $S$ be a solid bounded by two parallel planes perpendicular to the $x$-axis at $x = a$ and $x = b$. If the cross-sectional area of $S$ in the plane perpendicular to the $x$-axis at an arbitrary $x$ in $[a, b]$ is given by a continuous function $A(x)$, then the volume of the solid is $V = \int_a^b A(x)dx$. Formula for the Volume of a Solid by Slicing (Horizontal Cylinders): Let $S$ be a solid bounded by two parallel planes perpendicular to the $y$-axis at $y = c$ and $y = d$. If the cross-sectional area of $S$ in the plane perpendicular to the $y$-axis at an arbitrary $y$ in $[c, d]$ is given by a continuous function $A(y)$, then the volume of the solid is $V = \int_c^d A(y)dy$. 4.7 Mean Value Theorem for Integrals Theorem 4.7.1 (Comparison Property of Integrals): If the functions $f$ and $g$ are integrable on $[a, b]$, and if $f(x) \ge g(x)$ for all $x \in [a, b]$, then $\int_a^b f(x)dx \ge \int_a^b g(x)dx$. Theorem 4.7.2 (Bounds for Integrals): Suppose $f$ is continuous on the closed interval $[a, b]$. If $m$ and $M$ are the absolute minimum function value and absolute maximum function value, respectively, of $f$ in $[a, b]$, then $m(b - a) \le \int_a^b f(x)dx \le M(b - a)$. Theorem 4.7.3 (Mean Value Theorem for Integrals): If the function $f$ is continuous on the closed interval $[a, b]$, then there exists a number $c$ in $[a, b]$ such that $\int_a^b f(x)dx = f(c)(b - a)$. Definition (Average Value of a Function): If the function $f$ is integrable on $[a, b]$, the average value of $f$ on $[a, b]$ is $f_{ave} = \frac{1}{b - a} \int_a^b f(x)dx$.