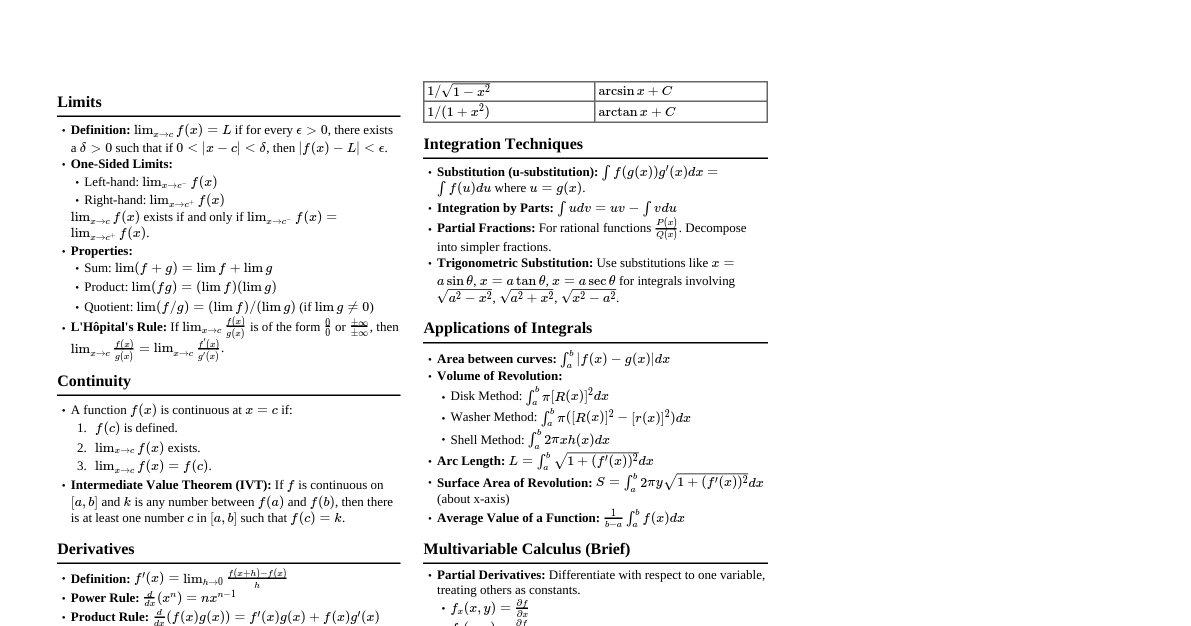

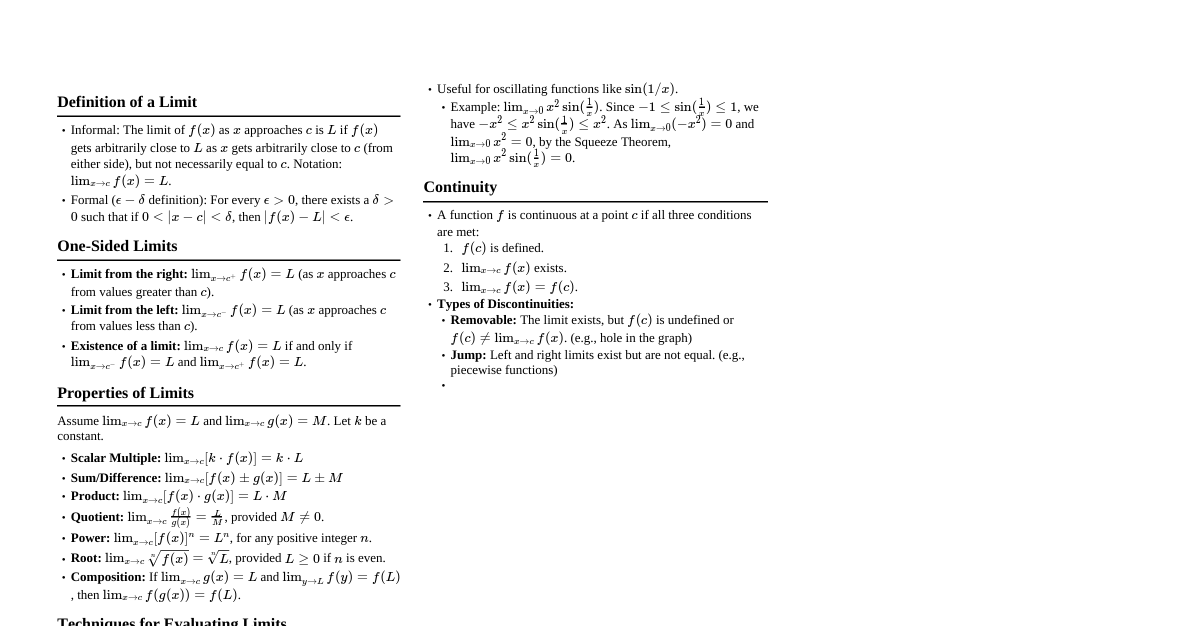

Long Exam 1 1. Polynomial, Rational, and Radical Functions Polynomial: $P(x) = a_n x^n + a_{n-1} x^{n-1} + \dots + a_1 x + a_0$ Domain: All real numbers $(-\infty, \infty)$ Degree: $n$ (highest power of $x$) Rational: $R(x) = \frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}$, where $P(x), Q(x)$ are polynomials. Domain: All real numbers except where $Q(x)=0$. Vertical Asymptotes: $x=c$ if $Q(c)=0$ and $P(c) \neq 0$. Horizontal Asymptotes: If deg($P$) If deg($P$) = deg($Q$), $y = \frac{\text{leading coeff of } P}{\text{leading coeff of } Q}$. If deg($P$) > deg($Q$), no horizontal asymptote (slant asymptote if deg($P$) = deg($Q$)+1). Radical: $f(x) = \sqrt[n]{g(x)}$ If $n$ is even, $g(x) \ge 0$. If $n$ is odd, domain is same as $g(x)$. 2. Piecewise, Absolute Value, Step Functions & Operations Piecewise Function: Defined by multiple sub-functions, each applying to a certain interval of the domain. Example: $f(x) = \begin{cases} x^2 & \text{if } x Absolute Value Function: $f(x) = |x| = \begin{cases} x & \text{if } x \ge 0 \\ -x & \text{if } x Step Function (e.g., Greatest Integer Function): $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$ (largest integer less than or equal to $x$) Example: $\lfloor 3.7 \rfloor = 3$, $\lfloor -1.2 \rfloor = -2$ Operations on Functions: Given $f(x)$ and $g(x)$ Sum: $(f+g)(x) = f(x) + g(x)$ Difference: $(f-g)(x) = f(x) - g(x)$ Product: $(fg)(x) = f(x)g(x)$ Quotient: $(\frac{f}{g})(x) = \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$, provided $g(x) \neq 0$ Composition: $(f \circ g)(x) = f(g(x))$ 3. Inverse Functions & Transcendental Functions Inverse Function ($f^{-1}(x)$): Exists if $f(x)$ is one-to-one (passes horizontal line test). Domain of $f$ is range of $f^{-1}$, and vice-versa. Property: $f(f^{-1}(x)) = x$ and $f^{-1}(f(x)) = x$. To find $f^{-1}(x)$: Replace $f(x)$ with $y$, swap $x$ and $y$, solve for $y$. Trigonometric Functions: $\sin x, \cos x, \tan x, \csc x, \sec x, \cot x$. Periodic. Inverse Circular (Trigonometric) Functions: $\arcsin x, \arccos x, \arctan x$, etc. $\arcsin x$: Domain $[-1, 1]$, Range $[-\pi/2, \pi/2]$ $\arccos x$: Domain $[-1, 1]$, Range $[0, \pi]$ $\arctan x$: Domain $(-\infty, \infty)$, Range $(-\pi/2, \pi/2)$ Exponential Function: $f(x) = a^x$, $a>0, a \neq 1$. Natural exponential: $e^x$, where $e \approx 2.71828$. Domain: $(-\infty, \infty)$, Range: $(0, \infty)$. Logarithmic Function: $f(x) = \log_a x$, inverse of $a^x$. Natural logarithm: $\ln x = \log_e x$. Domain: $(0, \infty)$, Range: $(-\infty, \infty)$. Properties: $\log_a(xy) = \log_a x + \log_a y$, $\log_a(x/y) = \log_a x - \log_a y$, $\log_a(x^p) = p \log_a x$. Change of Base: $\log_a x = \frac{\ln x}{\ln a}$. Hyperbolic Functions: $\sinh x = \frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{2}$ $\cosh x = \frac{e^x + e^{-x}}{2}$ $\tanh x = \frac{\sinh x}{\cosh x} = \frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{e^x + e^{-x}}$ Identity: $\cosh^2 x - \sinh^2 x = 1$ Inverse Hyperbolic Functions: $\text{arsinh } x = \ln(x + \sqrt{x^2+1})$ $\text{arcosh } x = \ln(x + \sqrt{x^2-1})$, for $x \ge 1$ $\text{artanh } x = \frac{1}{2} \ln\left(\frac{1+x}{1-x}\right)$, for $|x| 4. Limit of a Function and Limit Theorems Idea of a Limit: $\lim_{x \to c} f(x) = L$ means that as $x$ gets arbitrarily close to $c$ (but not equal to $c$), $f(x)$ gets arbitrarily close to $L$. Limit Theorems: If $\lim_{x \to c} f(x) = L$ and $\lim_{x \to c} g(x) = M$, then: Sum Rule: $\lim_{x \to c} [f(x) + g(x)] = L + M$ Difference Rule: $\lim_{x \to c} [f(x) - g(x)] = L - M$ Constant Multiple Rule: $\lim_{x \to c} [k \cdot f(x)] = k \cdot L$ Product Rule: $\lim_{x \to c} [f(x) \cdot g(x)] = L \cdot M$ Quotient Rule: $\lim_{x \to c} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \frac{L}{M}$, provided $M \neq 0$ Power Rule: $\lim_{x \to c} [f(x)]^n = L^n$ Root Rule: $\lim_{x \to c} \sqrt[n]{f(x)} = \sqrt[n]{L}$, provided $\sqrt[n]{L}$ is a real number. Direct Substitution Property: If $f$ is a polynomial or a rational function and $c$ is in the domain of $f$, then $\lim_{x \to c} f(x) = f(c)$. Techniques for Indeterminate Forms ($\frac{0}{0}$): Factoring & Canceling Rationalizing (multiplying by conjugate) 5. One-Sided Limits Left-Hand Limit: $\lim_{x \to c^-} f(x) = L$ (as $x$ approaches $c$ from values less than $c$) Right-Hand Limit: $\lim_{x \to c^+} f(x) = L$ (as $x$ approaches $c$ from values greater than $c$) Existence of a Limit: $\lim_{x \to c} f(x) = L$ if and only if $\lim_{x \to c^-} f(x) = L$ and $\lim_{x \to c^+} f(x) = L$. 6. Infinite Limits and Limits at Infinity Infinite Limits: $\lim_{x \to c} f(x) = \pm \infty$ Occur when $f(x)$ grows without bound as $x$ approaches $c$. Often associated with vertical asymptotes. Example: $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1}{x^2} = \infty$, $\lim_{x \to 0^+} \frac{1}{x} = \infty$, $\lim_{x \to 0^-} \frac{1}{x} = -\infty$. Limits at Infinity: $\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L$ or $\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = L$ Occur when $x$ grows without bound (positive or negative). Often associated with horizontal asymptotes (where $y=L$). Key fact: For any $k > 0$, $\lim_{x \to \pm \infty} \frac{1}{x^k} = 0$. For rational functions, divide numerator and denominator by the highest power of $x$ in the denominator. 7. Formal Definition of a Limit ($\epsilon-\delta$ Definition) $\lim_{x \to c} f(x) = L$ means: For every $\epsilon > 0$, there exists a $\delta > 0$ such that if $0 Graphically: For any $\epsilon$-interval around $L$ on the y-axis, we can find a $\delta$-interval around $c$ on the x-axis such that all $f(x)$ values (for $x$ in the $\delta$-interval, $x \neq c$) fall within the $\epsilon$-interval. 8. Continuity of a Function, Types of Discontinuities Definition of Continuity at a Point $c$: A function $f$ is continuous at $c$ if all three conditions are met: $f(c)$ is defined (c is in the domain of $f$). $\lim_{x \to c} f(x)$ exists. $\lim_{x \to c} f(x) = f(c)$. Continuity on an Interval: A function is continuous on an open interval $(a,b)$ if it is continuous at every point in the interval. It is continuous on a closed interval $[a,b]$ if it's continuous on $(a,b)$ and $\lim_{x \to a^+} f(x) = f(a)$ and $\lim_{x \to b^-} f(x) = f(b)$. Types of Discontinuities: Removable Discontinuity (Hole): $\lim_{x \to c} f(x)$ exists, but $f(c)$ is undefined or $f(c) \neq \lim_{x \to c} f(x)$. Can be "removed" by redefining $f(c)$. Jump Discontinuity: The left-hand limit and right-hand limit both exist but are not equal ($\lim_{x \to c^-} f(x) \neq \lim_{x \to c^+} f(x)$). (Common in piecewise functions) Infinite Discontinuity: One or both of the one-sided limits are $\pm \infty$. (Associated with vertical asymptotes) 9. Intermediate Value Theorem (IVT) & Squeeze Theorem Intermediate Value Theorem (IVT): If $f$ is continuous on the closed interval $[a, b]$, and $k$ is any number between $f(a)$ and $f(b)$, then there exists at least one number $c$ in $(a, b)$ such that $f(c) = k$. Application: Proving existence of roots. If $f(a)$ and $f(b)$ have opposite signs, then there's a root between $a$ and $b$. Squeeze Theorem (Sandwich Theorem): If $g(x) \le f(x) \le h(x)$ for all $x$ in an open interval containing $c$ (except possibly at $c$ itself), and if $\lim_{x \to c} g(x) = L$ and $\lim_{x \to c} h(x) = L$, then $\lim_{x \to c} f(x) = L$. Application: Useful for limits involving oscillating functions (e.g., $\sin(1/x)$). 10. Limits and Continuity of Trigonometric Functions, Inverse Circular, Exponential, Logarithmic, Hyperbolic, and Inverse Hyperbolic Functions Trigonometric Functions: $\sin x$, $\cos x$ are continuous everywhere. $\tan x$, $\sec x$ are continuous on their domains (not at $\pi/2 + n\pi$). $\cot x$, $\csc x$ are continuous on their domains (not at $n\pi$). Important Trigonometric Limits: $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\sin x}{x} = 1$ $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1 - \cos x}{x} = 0$ $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\tan x}{x} = 1$ Inverse Circular Functions: $\arcsin x$, $\arccos x$, $\arctan x$ are continuous on their domains. Exponential Functions: $a^x$ (and $e^x$) are continuous everywhere. Logarithmic Functions: $\log_a x$ (and $\ln x$) are continuous on their domains $(0, \infty)$. Hyperbolic Functions: $\sinh x$, $\cosh x$ are continuous everywhere. $\tanh x$ is continuous everywhere. Inverse Hyperbolic Functions: $\text{arsinh } x = \ln(x + \sqrt{x^2+1})$ $\text{arcosh } x = \ln(x + \sqrt{x^2-1})$, for $x \ge 1$ $\text{artanh } x = \frac{1}{2} \ln\left(\frac{1+x}{1-x}\right)$, for $|x| Long Exam 2 1. Derivatives (including Trigonometric Functions), Differentiation Rules, and Higher–Order Derivatives, Tangent & Normal Lines Definition of Derivative: $f'(x) = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h}$ or $f'(c) = \lim_{x \to c} \frac{f(x) - f(c)}{x - c}$ Represents the slope of the tangent line to $f(x)$ at $x$. Represents instantaneous rate of change of $f(x)$. Differentiation Rules: Constant Rule: $\frac{d}{dx}(c) = 0$ Power Rule: $\frac{d}{dx}(x^n) = nx^{n-1}$ Constant Multiple Rule: $\frac{d}{dx}(cf(x)) = c f'(x)$ Sum/Difference Rule: $\frac{d}{dx}(f(x) \pm g(x)) = f'(x) \pm g'(x)$ Product Rule: $\frac{d}{dx}(f(x)g(x)) = f'(x)g(x) + f(x)g'(x)$ Quotient Rule: $\frac{d}{dx}\left(\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}\right) = \frac{f'(x)g(x) - f(x)g'(x)}{[g(x)]^2}$ Derivatives of Trigonometric Functions: $\frac{d}{dx}(\sin x) = \cos x$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\cos x) = -\sin x$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\tan x) = \sec^2 x$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\csc x) = -\csc x \cot x$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\sec x) = \sec x \tan x$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\cot x) = -\csc^2 x$ Higher-Order Derivatives: $f''(x) = \frac{d}{dx}(f'(x))$, $f'''(x) = \frac{d}{dx}(f''(x))$, etc. Tangent Line: Equation $y - y_0 = m(x - x_0)$, where $m = f'(x_0)$. Normal Line: Equation $y - y_0 = -\frac{1}{m}(x - x_0)$, where $m = f'(x_0)$ and $m \neq 0$. 2. Differentiability and the Chain Rule Differentiability: A function $f$ is differentiable at $x=c$ if $f'(c)$ exists. If $f$ is differentiable at $c$, then $f$ is continuous at $c$. A function is NOT differentiable at: Corners (e.g., $f(x)=|x|$ at $x=0$) Cusps (e.g., $f(x)=x^{2/3}$ at $x=0$) Vertical Tangents (e.g., $f(x)=x^{1/3}$ at $x=0$) Discontinuities Chain Rule: $\frac{d}{dx}[f(g(x))] = f'(g(x)) \cdot g'(x)$ Alternatively, if $y=f(u)$ and $u=g(x)$, then $\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{dy}{du} \cdot \frac{du}{dx}$. 3. Implicit Differentiation Used to find the derivative of functions where $y$ is not explicitly defined as a function of $x$ (e.g., $x^2 + y^2 = 25$). Steps: Differentiate both sides of the equation with respect to $x$. Remember to multiply by $\frac{dy}{dx}$ when differentiating terms involving $y$. Solve the resulting equation for $\frac{dy}{dx}$. 4. Derivatives of Exponential and Logarithmic Functions $\frac{d}{dx}(e^x) = e^x$ $\frac{d}{dx}(a^x) = a^x \ln a$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\ln x) = \frac{1}{x}$ (for $x>0$) $\frac{d}{dx}(\log_a x) = \frac{1}{x \ln a}$ (for $x>0$) Using Chain Rule: $\frac{d}{dx}(e^{u(x)}) = e^{u(x)} u'(x)$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\ln(u(x))) = \frac{u'(x)}{u(x)}$ 5. Logarithmic Differentiation Used for functions of the form $y = [f(x)]^{g(x)}$ or complex products/quotients. Steps: Take the natural logarithm of both sides: $\ln y = \ln[f(x)]^{g(x)} = g(x) \ln f(x)$. Differentiate both sides implicitly with respect to $x$: $\frac{1}{y}\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{d}{dx}[g(x) \ln f(x)]$. Solve for $\frac{dy}{dx}$: $\frac{dy}{dx} = y \cdot \frac{d}{dx}[g(x) \ln f(x)]$. Substitute back $y = [f(x)]^{g(x)}$. 6. Derivatives of Inverse Circular, Hyperbolic, and Inverse Hyperbolic Functions Inverse Circular (Trigonometric): $\frac{d}{dx}(\arcsin x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\arccos x) = -\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\arctan x) = \frac{1}{1+x^2}$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\text{arccot } x) = -\frac{1}{1+x^2}$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\text{arcsec } x) = \frac{1}{|x|\sqrt{x^2-1}}$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\text{arccsc } x) = -\frac{1}{|x|\sqrt{x^2-1}}$ Hyperbolic: $\frac{d}{dx}(\sinh x) = \cosh x$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\cosh x) = \sinh x$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\tanh x) = \text{sech}^2 x$ Inverse Hyperbolic: $\frac{d}{dx}(\text{arsinh } x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1+x^2}}$ $\frac{d}{dx}(\text{arcosh } x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2-1}}$ (for $x>1$) $\frac{d}{dx}(\text{artanh } x) = \frac{1}{1-x^2}$ (for $|x| 7. Indeterminate Forms, L'Hôpital's Rule Indeterminate Forms: $\frac{0}{0}, \frac{\infty}{\infty}, 0 \cdot \infty, \infty - \infty, 1^\infty, 0^0, \infty^0$. L'Hôpital's Rule: If $\lim_{x \to c} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$ is of the form $\frac{0}{0}$ or $\frac{\infty}{\infty}$, then $\lim_{x \to c} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \lim_{x \to c} \frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)}$, provided the latter limit exists. Strategies for other indeterminate forms: $0 \cdot \infty$: Rewrite as $\frac{f}{1/g}$ or $\frac{g}{1/f}$ to get $\frac{0}{0}$ or $\frac{\infty}{\infty}$. $\infty - \infty$: Combine terms (e.g., common denominator) to get $\frac{0}{0}$ or $\frac{\infty}{\infty}$. $1^\infty, 0^0, \infty^0$: Use logarithms. Let $y = f(x)^{g(x)}$, then $\ln y = g(x) \ln f(x)$. Evaluate $\lim \ln y$, then exponentiate the result. 8. Mean Value Theorem, Relative Extrema, First Derivative Test for Relative Extrema Mean Value Theorem (MVT): If $f$ is continuous on $[a, b]$ and differentiable on $(a, b)$, then there exists a number $c$ in $(a, b)$ such that $f'(c) = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a}$. Critical Numbers: Values $c$ in the domain of $f$ where $f'(c) = 0$ or $f'(c)$ is undefined. Relative extrema can only occur at critical numbers. Relative Extrema (Local Max/Min): A function $f$ has a relative maximum at $c$ if $f(c) \ge f(x)$ for all $x$ in an open interval containing $c$. A function $f$ has a relative minimum at $c$ if $f(c) \le f(x)$ for all $x$ in an open interval containing $c$. First Derivative Test: Let $c$ be a critical number of $f$. If $f'(x)$ changes from positive to negative at $c$, then $f$ has a relative maximum at $c$. If $f'(x)$ changes from negative to positive at $c$, then $f$ has a relative minimum at $c$. If $f'(x)$ does not change sign at $c$, then $f$ has no relative extremum at $c$. 9. Concavity, Second Derivative Test for Relative Extrema Concavity: $f$ is concave up on an interval if $f''(x) > 0$ on that interval (graph holds water). $f$ is concave down on an interval if $f''(x) Inflection Point: A point $(c, f(c))$ where the concavity of $f$ changes. Occurs where $f''(c) = 0$ or $f''(c)$ is undefined, AND $f''(x)$ changes sign. Second Derivative Test: Let $c$ be a critical number where $f'(c) = 0$. If $f''(c) > 0$, then $f$ has a relative minimum at $c$. If $f''(c) If $f''(c) = 0$ or is undefined, the test is inconclusive (use First Derivative Test). 10. Curve Tracing with Derivatives, Graph of $f$ from $f'$ Steps for Curve Tracing (Graphing): Find domain, intercepts (x- and y-). Check for symmetries (even/odd). Find asymptotes (vertical, horizontal, slant). Find $f'(x)$: Determine critical numbers, intervals of increase/decrease, relative extrema (using First Derivative Test). Find $f''(x)$: Determine intervals of concavity, inflection points (using Second Derivative Test if applicable). Plot key points (intercepts, extrema, inflection points) and sketch the graph using the information gathered. Graph of $f$ from $f'$: If $f'(x) > 0$, $f(x)$ is increasing. If $f'(x) If $f'(x) = 0$ and changes sign, $f(x)$ has a local extremum. If $f'(x)$ is increasing, $f(x)$ is concave up ($f''(x)>0$). If $f'(x)$ is decreasing, $f(x)$ is concave down ($f''(x) Points where $f'(x)$ has a local extremum correspond to inflection points of $f(x)$. Long Exam 3 1. Absolute Extrema, Extreme Value Theorem Absolute Extrema: The maximum or minimum value a function takes over its entire domain or a specified interval. Absolute Maximum: $f(c)$ is an absolute maximum if $f(c) \ge f(x)$ for all $x$ in the domain. Absolute Minimum: $f(c)$ is an absolute minimum if $f(c) \le f(x)$ for all $x$ in the domain. Extreme Value Theorem (EVT): If $f$ is continuous on a closed interval $[a, b]$, then $f$ attains both an absolute maximum value and an absolute minimum value on that interval. Finding Absolute Extrema on a Closed Interval $[a, b]$: Find all critical numbers of $f$ in $(a, b)$. Evaluate $f$ at all critical numbers found in step 1. Evaluate $f$ at the endpoints $a$ and $b$. The largest of these values is the absolute maximum, and the smallest is the absolute minimum. 2. Optimization Problems Steps to solve optimization problems: Understand the problem: Read carefully, identify given information and what needs to be optimized (maximized/minimized). Draw a diagram (if applicable) and label quantities. Introduce notation: Assign variables to quantities. Write the primary equation: The formula for the quantity to be optimized. Write the secondary equation(s): Constraints or relationships between variables. Reduce to a single variable: Use secondary equations to express the primary equation in terms of one independent variable. Determine the domain of the primary equation. Find the absolute extrema: Use calculus techniques (First or Second Derivative Test, or EVT for closed intervals). State the final answer, ensuring it addresses the original question. 3. Rates of Change, Rectilinear Motion Rates of Change: The derivative $f'(x)$ represents the instantaneous rate of change of $f(x)$ with respect to $x$. Rectilinear Motion (Motion along a line): Position: $s(t)$ (function of time $t$) Velocity: $v(t) = s'(t) = \frac{ds}{dt}$ Speed: $|v(t)|$ Object is moving right when $v(t) > 0$. Object is moving left when $v(t) Object is at rest when $v(t) = 0$. Acceleration: $a(t) = v'(t) = s''(t) = \frac{d^2s}{dt^2}$ Object is speeding up when $v(t)$ and $a(t)$ have the same sign. Object is slowing down when $v(t)$ and $a(t)$ have opposite signs. 4. Related Rates Problems where the rates of change of two or more related quantities are given or need to be found. Steps to solve related rates problems: Understand the problem: Identify knowns and unknowns, especially rates. Draw a diagram, labeling quantities that change over time with variables. Write an equation relating the quantities. Differentiate both sides of the equation with respect to time ($t$). Remember the Chain Rule for any variable that is a function of $t$. Substitute the known values (including the rates) into the differentiated equation. Solve for the unknown rate. State the answer with correct units. 5. Local Linear Approximation, Differentials Local Linear Approximation (Linearization): The tangent line to a function $f(x)$ at a point $(a, f(a))$ can be used to approximate the function's values near $a$. The linearization of $f(x)$ at $x=a$ is $L(x) = f(a) + f'(a)(x-a)$. For $x$ near $a$, $f(x) \approx L(x)$. Differentials: For a function $y = f(x)$, the differential $dx$ is an independent variable (often $\Delta x$). The differential $dy$ is defined as $dy = f'(x) dx$. $dy$ represents the change in the tangent line (approximation of $\Delta y$). $\Delta y = f(x + \Delta x) - f(x)$ represents the actual change in $y$. For small $\Delta x$, $dy \approx \Delta y$. This provides an estimate for the change in $y$ or for $f(x+\Delta x) \approx f(x) + dy$. Long Exam 4 1. Antiderivatives, Antidifferentiation Rules (including some Trigonometric Functions) Antiderivative: A function $F(x)$ is an antiderivative of $f(x)$ if $F'(x) = f(x)$. Indefinite Integral: The set of all antiderivatives of $f(x)$, denoted by $\int f(x) dx = F(x) + C$, where $C$ is the constant of integration. Antidifferentiation Rules: Power Rule: $\int x^n dx = \frac{x^{n+1}}{n+1} + C$, for $n \neq -1$. Constant Multiple Rule: $\int cf(x) dx = c \int f(x) dx$. Sum/Difference Rule: $\int [f(x) \pm g(x)] dx = \int f(x) dx \pm \int g(x) dx$. $\int k dx = kx + C$. Antiderivatives of Trigonometric Functions: $\int \cos x dx = \sin x + C$ $\int \sin x dx = -\cos x + C$ $\int \sec^2 x dx = \tan x + C$ $\int \csc^2 x dx = -\cot x + C$ $\int \sec x \tan x dx = \sec x + C$ $\int \csc x \cot x dx = -\csc x + C$ 2. Integration by Substitution (u-Substitution) Used to integrate composite functions. If $u = g(x)$, then $du = g'(x) dx$. The integral $\int f(g(x))g'(x) dx$ becomes $\int f(u) du$. Steps: Choose a substitution $u = g(x)$. Calculate $du = g'(x) dx$. Rewrite the integral entirely in terms of $u$ and $du$. Evaluate the new integral. Substitute back $g(x)$ for $u$ to express the answer in terms of $x$. For definite integrals, change the limits of integration according to $u=g(x)$. 3. Antiderivatives involving Logarithmic and Exponential Functions $\int \frac{1}{x} dx = \ln|x| + C$ $\int e^x dx = e^x + C$ $\int a^x dx = \frac{a^x}{\ln a} + C$ Using u-substitution: $\int \frac{g'(x)}{g(x)} dx = \ln|g(x)| + C$ $\int e^{g(x)} g'(x) dx = e^{g(x)} + C$ 4. Antiderivatives involving Inverse Trigonometric Functions, Antiderivatives of Hyperbolic Functions Inverse Trigonometric Forms: $\int \frac{1}{\sqrt{a^2-x^2}} dx = \arcsin\left(\frac{x}{a}\right) + C$ $\int \frac{1}{a^2+x^2} dx = \frac{1}{a}\arctan\left(\frac{x}{a}\right) + C$ $\int \frac{1}{x\sqrt{x^2-a^2}} dx = \frac{1}{a}\text{arcsec}\left|\frac{x}{a}\right| + C$ Hyperbolic Antiderivatives: $\int \cosh x dx = \sinh x + C$ $\int \sinh x dx = \cosh x + C$ $\int \text{sech}^2 x dx = \tanh x + C$ 5. Antiderivatives involving Inverse Hyperbolic Functions $\int \frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2+a^2}} dx = \text{arsinh}\left(\frac{x}{a}\right) + C = \ln\left|x+\sqrt{x^2+a^2}\right| + C$ $\int \frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2-a^2}} dx = \text{arcosh}\left(\frac{x}{a}\right) + C = \ln\left|x+\sqrt{x^2-a^2}\right| + C$ (for $x>a$) $\int \frac{1}{a^2-x^2} dx = \frac{1}{a}\text{artanh}\left(\frac{x}{a}\right) + C = \frac{1}{2a}\ln\left|\frac{a+x}{a-x}\right| + C$ (for $|x| 6. Differential Equations, Particular Antiderivatives Differential Equation: An equation that involves a function and its derivatives. General Solution: The family of all functions that satisfy a differential equation (includes the constant $C$). Particular Antiderivative/Solution: A specific solution obtained by using an initial condition (a point $(x_0, y_0)$ that the solution curve passes through) to determine the value of $C$. To find a particular antiderivative: Find the general antiderivative (indefinite integral). Use the initial condition to solve for $C$. Substitute the value of $C$ back into the general solution. 7. Rectilinear Motion Revisited Using Antiderivatives: Given acceleration $a(t)$, integrate to find velocity $v(t)$: $v(t) = \int a(t) dt + C_1$. Use initial velocity $v(0)$ to find $C_1$. Given velocity $v(t)$, integrate to find position $s(t)$: $s(t) = \int v(t) dt + C_2$. Use initial position $s(0)$ to find $C_2$. Total Distance Traveled: $\int_a^b |v(t)| dt$. Requires finding when $v(t)$ changes sign and splitting the integral. Displacement: $\int_a^b v(t) dt = s(b) - s(a)$. 8. The Definite Integral, Properties of the Definite Integral Definite Integral (Riemann Sum): $\int_a^b f(x) dx = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=1}^n f(x_i^*) \Delta x$. Represents the net signed area between $f(x)$ and the x-axis from $a$ to $b$. Properties: $\int_a^b f(x) dx = -\int_b^a f(x) dx$ $\int_a^a f(x) dx = 0$ $\int_a^b c f(x) dx = c \int_a^b f(x) dx$ $\int_a^b [f(x) \pm g(x)] dx = \int_a^b f(x) dx \pm \int_a^b g(x) dx$ $\int_a^c f(x) dx + \int_c^b f(x) dx = \int_a^b f(x) dx$ If $f(x) \ge 0$ on $[a,b]$, then $\int_a^b f(x) dx \ge 0$. If $f(x) \ge g(x)$ on $[a,b]$, then $\int_a^b f(x) dx \ge \int_a^b g(x) dx$. 9. Fundamental Theorems of Calculus (FTC) FTC Part 1: If $f$ is continuous on $[a, b]$, then the function $G(x) = \int_a^x f(t) dt$ has a derivative at every point in $(a, b)$, and $G'(x) = f(x)$. Also, $\frac{d}{dx} \int_a^{g(x)} f(t) dt = f(g(x))g'(x)$. FTC Part 2: If $f$ is continuous on $[a, b]$ and $F$ is any antiderivative of $f$, then $\int_a^b f(x) dx = F(b) - F(a)$. 10. Mean Value Theorem for Integrals, Average Value Mean Value Theorem for Integrals: If $f$ is continuous on $[a, b]$, then there exists a number $c$ in $[a, b]$ such that $\int_a^b f(x) dx = f(c)(b-a)$. Average Value of a Function: The average value of $f$ on $[a, b]$ is $f_{\text{avg}} = \frac{1}{b-a} \int_a^b f(x) dx$. 11. Area and Arc Length Area Between Curves: If $f(x) \ge g(x)$ on $[a,b]$, the area between curves is $A = \int_a^b [f(x) - g(x)] dx$. If curves intersect, split the integral at intersection points. Can also integrate with respect to $y$: $A = \int_c^d [f(y) - g(y)] dy$. Arc Length: The length of a curve $y=f(x)$ from $x=a$ to $x=b$ is $L = \int_a^b \sqrt{1 + [f'(x)]^2} dx$. For a curve $x=g(y)$ from $y=c$ to $y=d$, $L = \int_c^d \sqrt{1 + [g'(y)]^2} dy$. 12. Volume of Solids of Revolution, Volume by Slicing Volume by Slicing (General Method): If a solid lies between $x=a$ and $x=b$, and the cross-sectional area perpendicular to the x-axis is $A(x)$, then $V = \int_a^b A(x) dx$. (Similarly for y-axis). Volume of Solids of Revolution: Disk Method: For a region revolved around an axis (no hole). About x-axis: $V = \int_a^b \pi [R(x)]^2 dx$ About y-axis: $V = \int_c^d \pi [R(y)]^2 dy$ Washer Method: For a region revolved around an axis (with a hole). About x-axis: $V = \int_a^b \pi ([R(x)]^2 - [r(x)]^2) dx$ (Outer radius $R(x)$, Inner radius $r(x)$) About y-axis: $V = \int_c^d \pi ([R(y)]^2 - [r(y)]^2) dy$ Cylindrical Shell Method: About y-axis: $V = \int_a^b 2\pi x h(x) dx$ (Radius $x$, Height $h(x)$) About x-axis: $V = \int_c^d 2\pi y h(y) dy$ (Radius $y$, Height $h(y)$)