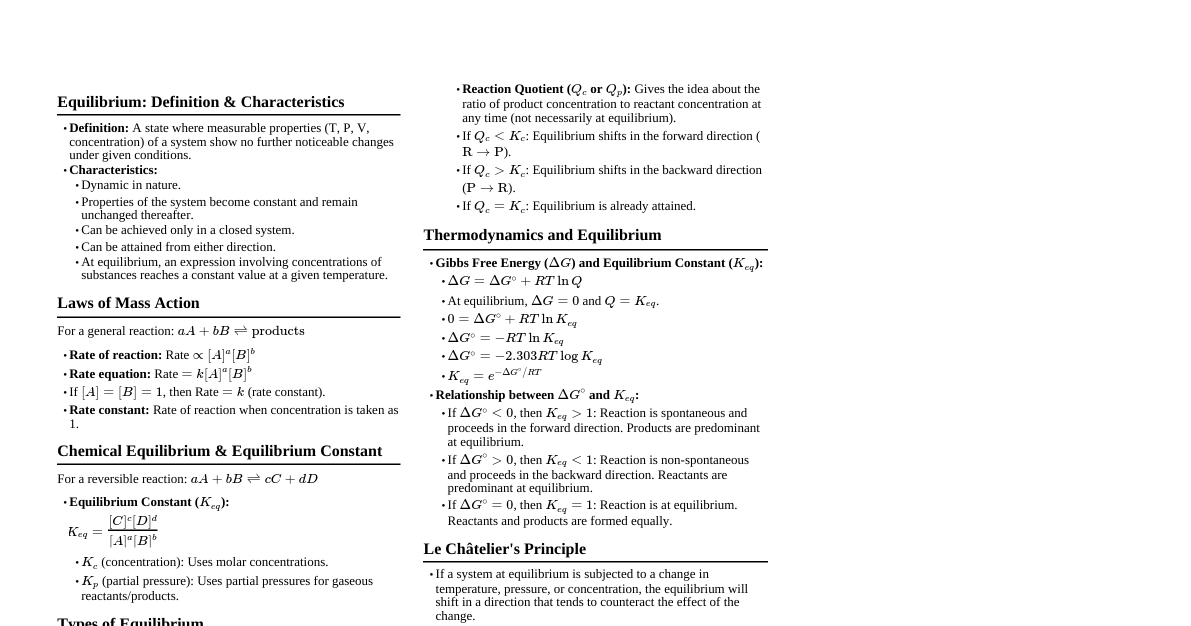

Equilibrium Basics Definition: A state where measurable properties remain constant under given conditions. Physical Equilibrium: Equilibrium achieved in physical processes. Chemical Equilibrium: Equilibrium achieved in chemical processes. Types of Physical Equilibrium 1. Solid – Liquid Equilibrium Example: Ice and water $H_2O_{(s)} \rightleftharpoons H_2O_{(l)}$ (Rate of melting = Rate of freezing) 2. Liquid – Vapour Equilibrium Example: Water and water vapour $H_2O_{(l)} \rightleftharpoons H_2O_{(g)}$ (Rate of evaporation = Rate of condensation) 3. Solid – Vapour Equilibrium Example: Iodine, Camphor, Ammonium chloride $I_{2(s)} \rightleftharpoons I_{2(g)}$ (Rate of sublimation = Rate of condensation) 4. Dissolution of Solids/Gases in Liquids Solids in liquids: Sugar in water In a saturated solution, dynamic equilibrium exists between undissolved sugar and its solution. Sugar$_{(solid)} \rightleftharpoons$ Sugar$_{(in\,solution)}$ (Rate of dissolution = Rate of crystallization) Gases in liquids: Henry's Law: The mass of a gas dissolved in a given mass of solvent at any temperature is proportional to the pressure of the gas above the solvent. Example: $CO_{2(gas)} \rightleftharpoons CO_{2(in\,solution)}$ Characteristics of Equilibrium Physical Equilibrium Closed system Dynamic Measurable properties become constant Magnitude indicates extent of the reaction Chemical Equilibrium Dynamic: Rate of forward reaction = Rate of backward reaction Measurable properties become constant at equilibrium. Possible only in closed system. Can be approached from either directions. Law of Mass Action (Guldberg and Waage) At constant temperature, the rate of a reaction is directly proportional to the product of molar concentrations of reactants, each raised to the power equal to its coefficient in the balanced chemical equation. For $A + B \rightarrow Product$: Rate $\propto [A][B]$ Rate $= k[A][B]$, where $k$ is the rate constant. For $aA + bB \rightarrow Products$: Rate $\propto [A]^a[B]^b$ Equilibrium Constant (K) For a reversible reaction $aA + bB \rightleftharpoons xX + yY$: Rate of forward reaction $= K_f[A]^a[B]^b$ Rate of backward reaction $= K_b[X]^x[Y]^y$ At equilibrium: $K_f[A]^a[B]^b = K_b[X]^x[Y]^y$ Equilibrium Constant $K = \frac{K_f}{K_b} = \frac{[X]^x[Y]^y}{[A]^a[B]^b}$ Equilibrium Law: Ratio of the product of molecular concentrations of products to that of reactants, each raised to a power equal to its coefficient in the balanced chemical equation. Relation between $K_p$ and $K_c$ $K_p = K_c(RT)^{\Delta n}$ $R$: Universal gas constant $T$: Temperature (in Kelvin) $\Delta n$: (Number of moles of gaseous products) - (Number of moles of gaseous reactants) Types of Equilibrium 1. Homogeneous Equilibrium Reactants and products are in the same phase. Example: $N_{2(g)} + 3H_{2(g)} \rightleftharpoons 2NH_{3(g)}$ Example: $CH_3CH_2OH_{(l)} + CH_3COOH_{(l)} \rightleftharpoons CH_3COOC_2H_{5(l)} + H_2O_{(l)}$ 2. Heterogeneous Equilibrium Reactants and products are in different phases. Example: $CaCO_{3(s)} \rightleftharpoons CaO_{(s)} + CO_{2(g)}$ Features of Equilibrium Constant Applicable only in equilibrium state. Independent of initial concentration. Depends on temperature. Equilibrium constant for reverse reaction is the inverse of the forward reaction's constant. Factors Affecting Equilibrium (Le-Chatelier's Principle) If a system at equilibrium is subjected to a change in pressure, temperature, or concentration, the equilibrium shifts to nullify the effect of that change. Effect of Concentration Change: Increasing reactant concentration shifts equilibrium to decrease it (favors forward reaction). Example: $N_2 + 3H_2 \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3$. Adding $N_2$ or $H_2$ or removing $NH_3$ favors forward reaction. Effect of Temperature Change: Increasing temperature favors endothermic reactions. Decreasing temperature favors exothermic reactions. Example: $N_2 + 3H_2 \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3$ ($\Delta H = -93.5\,KJ\,mol^{-1}$). Increasing temperature favors decomposition of $NH_3$. Low temperature favors formation of $NH_3$. Effect of Pressure Change: Increasing pressure shifts equilibrium towards the side with fewer moles of gas. Example: $N_2 + 3H_2 \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3$. Increase in pressure favors formation of $NH_3$ (4 moles gas $\rightarrow$ 2 moles gas). Example: $2SO_2 + O_2 \rightleftharpoons 2SO_3$. Increase in pressure favors formation of $SO_3$. Example: $N_2O_4 \rightleftharpoons 2NO_2$. Increase in pressure favors formation of $N_2O_4$. Example: $H_2 + I_2 \rightleftharpoons 2HI$. Pressure has no effect (equal moles of gas on both sides). Effect of Catalyst: Alters the rate of both forward and backward reactions equally. Does not affect the position of equilibrium, but helps to achieve equilibrium quickly. Effect of Inert Gas Addition at Constant Volume: No effect on equilibrium as partial pressures remain constant. Ionic Equilibrium Strong Electrolytes: Undergo complete ionization in water (e.g., $NaCl, NaOH, HCl, H_2SO_4$). Weak Electrolytes: Undergo partial ionization in water (e.g., Acetic acid, $NH_4OH$). Acids, Bases and Salts Arrhenius Concept Acids dissociate to give $H^+$ ions in water (e.g., $HCl \rightarrow H^+ + Cl^-$ or $HCl + H_2O \rightarrow H_3O^+ + Cl^-$). Bases dissociate to give $OH^-$ ions in water (e.g., $NaOH \rightarrow Na^+ + OH^-$). Lowry-Bronsted Concept Acids are proton donors. Bases are proton acceptors. Example: $NH_{3(aq)} + H_2O_{(l)} \rightleftharpoons NH_4^+ {}_{(aq)} + OH^- {}_{(aq)}$ Conjugate Acid-Base Pair: Differs by only one proton. Strong acid has a weak conjugate base, and vice versa. Lewis Concept Acids are electron pair acceptors (e.g., $BF_3, AlCl_3, CO_2^+, Mg^{2+}$). Bases are electron pair donors (e.g., $H_2O, NH_3, OH^-$). pH Scale Defined as negative logarithm to base 10 of hydrogen or hydronium ion concentration. $pH = -log[H^+]$ or $pH = -log[H_3O^+]$ $pH > 7$: Basic $pH $pH = 7$: Neutral $pOH = -log[OH^-]$ $pH + pOH = 14 = pK_w$ Relation between $K_a$ and $K_b$ $K_a \times K_b = K_w$ $pK_a + pK_b = pK_w = 14$ Factors Affecting Acid Strength Depends on the strength and polarity of the H-A bond. Weaker H-A bond $\rightarrow$ easier dissociation $\rightarrow$ stronger acid. Greater polarity of H-A bond (due to higher electronegativity difference) $\rightarrow$ greater acidity. In a group: Acidity mainly determined by bond strength. As size of A increases, H-A bond strength decreases, so acid strength increases. Example: $HF In a period: Acidity mainly determined by polarity of the bond. As electronegativity of A increases, acid strength increases. Example: $CH_4 Hydrolysis of Salts and pH of Solutions Interaction of anion or cation (or both) of a salt with water. Cations of strong bases ($Na^+, K^+, Ca^{2+}$) and anions of strong acids ($Cl^-, Br^-, NO_3^-, ClO_4^-$) do not hydrolyze. Salts of strong acids and strong bases are neutral (pH = 7). 1. Hydrolysis of Salt of Strong Base and Weak Acid Examples: Sodium acetate ($CH_3COONa$), sodium carbonate ($Na_2CO_3$), potassium cyanide ($KCN$). Only the anion of the weak acid undergoes hydrolysis. Solution is basic ($pH > 7$). $pH = 7 + \frac{1}{2}(pK_a + \log C)$ where $C$ is the concentration of salt. 2. Hydrolysis of Salt of Weak Base and Strong Acid Examples: $NH_4Cl, NH_4NO_3, CuSO_4$. Only the cation of the weak base undergoes hydrolysis. Solution is acidic ($pH $pH = 7 - \frac{1}{2}(pK_b + \log C)$. 3. Hydrolysis of Salt of Weak Base and Weak Acid Examples: Ammonium acetate ($CH_3COONH_4$), ammonium carbonate ($ (NH_4)_2CO_3$). Both cation and anion undergo hydrolysis. Solution can be neutral, acidic, or basic depending on the relative strength of the acid and base formed. $pH = 7 + \frac{1}{2}(pK_a - pK_b)$. Common Ion Effect Suppression of the dissociation of a weak electrolyte by adding a strong electrolyte containing a common ion. Example: Dissociation of acetic acid ($CH_3COOH_{(aq)} \rightleftharpoons CH_3COO^- {}_{(aq)} + H^+ {}_{(aq)}$). Adding sodium acetate ($CH_3COONa$) increases $[CH_3COO^-]$ causing equilibrium to shift left, decreasing dissociation of acetic acid. Example: Dissociation of ammonium hydroxide ($NH_4OH_{(aq)} \rightleftharpoons NH_4^+ {}_{(aq)} + OH^- {}_{(aq)}$). Adding $NH_4Cl$ increases $[NH_4^+]$ causing equilibrium to shift left, decreasing dissociation of $NH_4OH$. Buffer Solutions Resist change in pH upon dilution or addition of small amounts of acid or alkali. Acidic Buffer: Mixture of a weak acid and its salt with a strong base (e.g., acetic acid and sodium acetate). Basic Buffer: Mixture of a weak base and its salt with a strong acid (e.g., $NH_4OH$ and $NH_4Cl$, around pH 9.25). Henderson-Hasselbalch Equation for Buffer Solutions Acidic Buffer For a weak acid $HA$ and its conjugate base $A^-$: $HA + H_2O \rightleftharpoons H_3O^+ + A^-$ $K_a = \frac{[H_3O^+][A^-]}{[HA]}$ $pH = pK_a + \log \frac{[Salt]}{[Acid]}$ Basic Buffer $pOH = pK_b + \log \frac{[Salt]}{[Base]}$ $pH = 14 - (pK_b + \log \frac{[Salt]}{[Base]})$ Solubility Product Constant ($K_{sp}$) For a sparingly soluble salt, an equilibrium exists between the undissolved solid and its ions in a saturated solution. Example: $BaSO_{4(s)} \rightleftharpoons Ba^{2+}_{(aq)} + SO_4^{2-}{}_{(aq)}$ $K_{sp} = [Ba^{2+}][SO_4^{2-}]$ (since $[BaSO_4]$ for a pure solid is constant). For a general salt $A_xB_y$: $A_xB_{y(s)} \rightleftharpoons xA^{y+}_{(aq)} + yB^{x-}_{(aq)}$ $K_{sp} = [A^{y+}]^x[B^{x-}]^y$ If $S$ is the molar solubility, for $BaSO_4$, $K_{sp} = S \times S = S^2$. If the ion concentrations are not at equilibrium, the product is called the ion product ($Q_{sp}$). At equilibrium, $K_{sp} = Q_{sp}$. If $K_{sp} > Q_{sp}$, dissolution occurs. If $K_{sp} Application: Purification of $NaCl$ by passing $HCl$ gas through its saturated solution, which increases $[Cl^-]$ and causes $NaCl$ to precipitate. Example Problems Q1) Calculate the pH of a 0.01 M acetic acid solution with the degree of ionization 0.045. Degree of ionization, $\alpha = 0.045$ $[H_3O^+] = c\alpha = 0.01 \times 0.045 = 4.5 \times 10^{-4} M$ $pH = -\log[H_3O^+] = -\log(4.5 \times 10^{-4}) = 3.3468$ Q2) Calculate the pH of an acidic buffer containing 0.1 M $CH_3COOH$ and 0.5 M $CH_3COONa$. [$K_a$ for $CH_3COOH$ is $1.8 \times 10^{-6}$]. For an acidic buffer, $pH = pK_a + \log \frac{[Salt]}{[Acid]}$ $[Acid] = 0.1 M$, $[Salt] = 0.5 M$ $pK_a = -\log K_a = -\log(1.8 \times 10^{-6}) = 5.7447$ $pH = 5.7447 + \log \frac{[0.5]}{[0.1]} = 5.7447 + \log(5) = 5.7447 + 0.6990 = 6.4437$ Q3) The solubility of $Mg(OH)_2$ at 298K is $1.5 \times 10^{-4}$. Calculate the solubility product. $Mg(OH)_{2(s)} \rightleftharpoons Mg^{2+}_{(aq)} + 2OH^-_{(aq)}$ If solubility is $S$, then $[Mg^{2+}] = S$ and $[OH^-] = 2S$ $K_{sp} = [Mg^{2+}][OH^-]^2 = (S)(2S)^2 = 4S^3$ Given $S = 1.5 \times 10^{-4}$ $K_{sp} = 4 \times (1.5 \times 10^{-4})^3 = 4 \times (3.375 \times 10^{-12}) = 1.35 \times 10^{-11}$