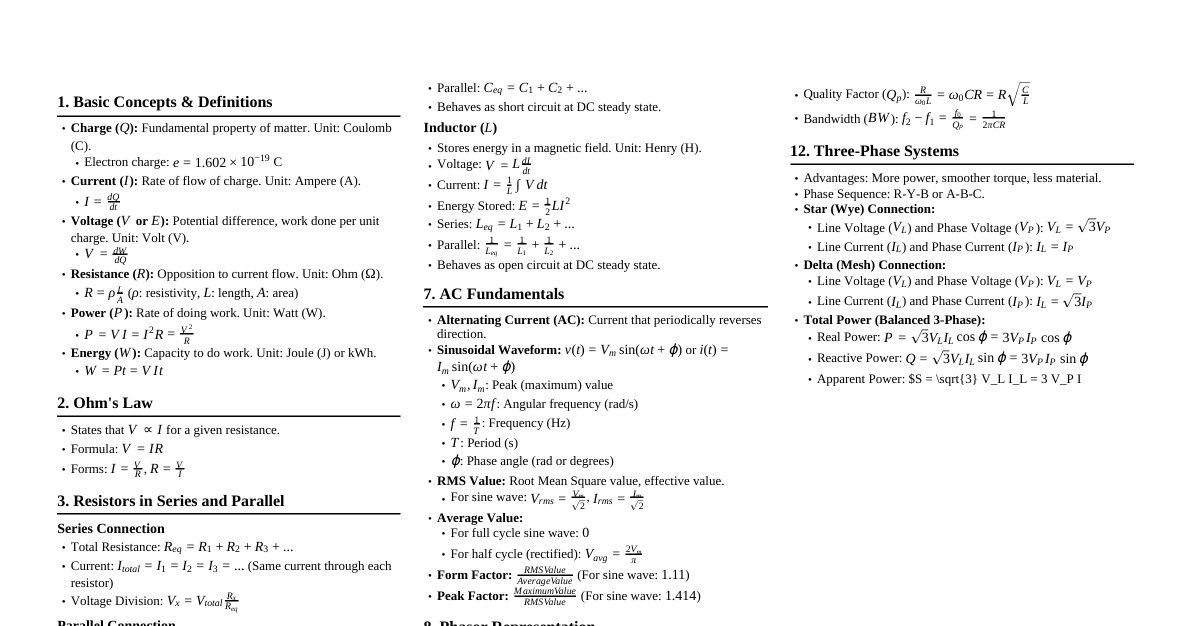

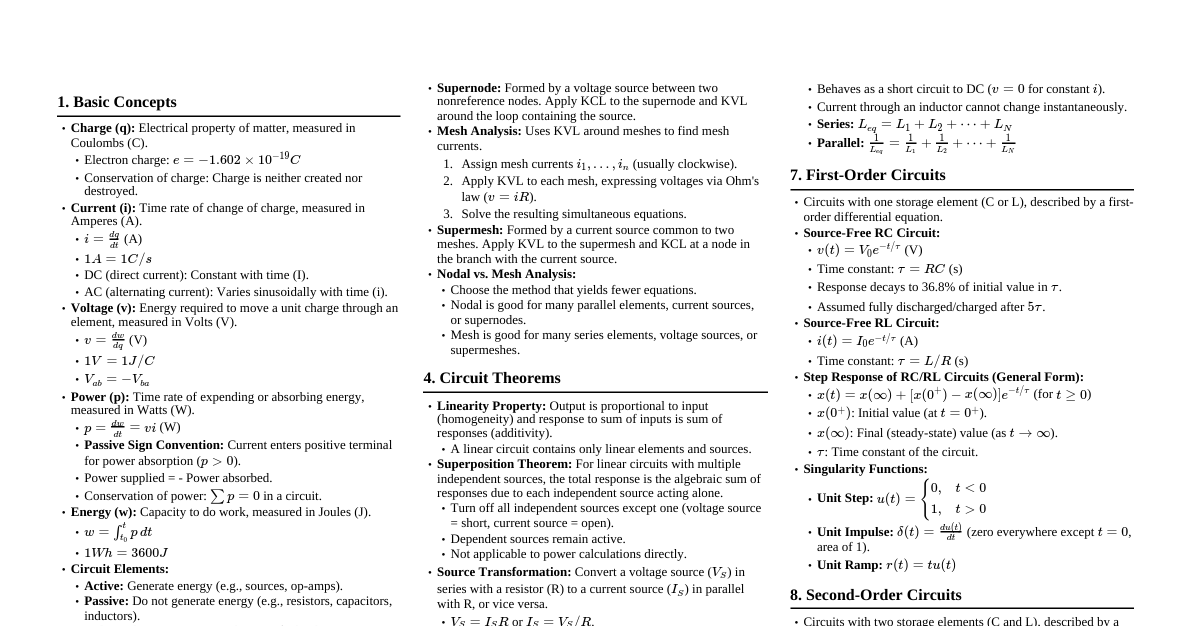

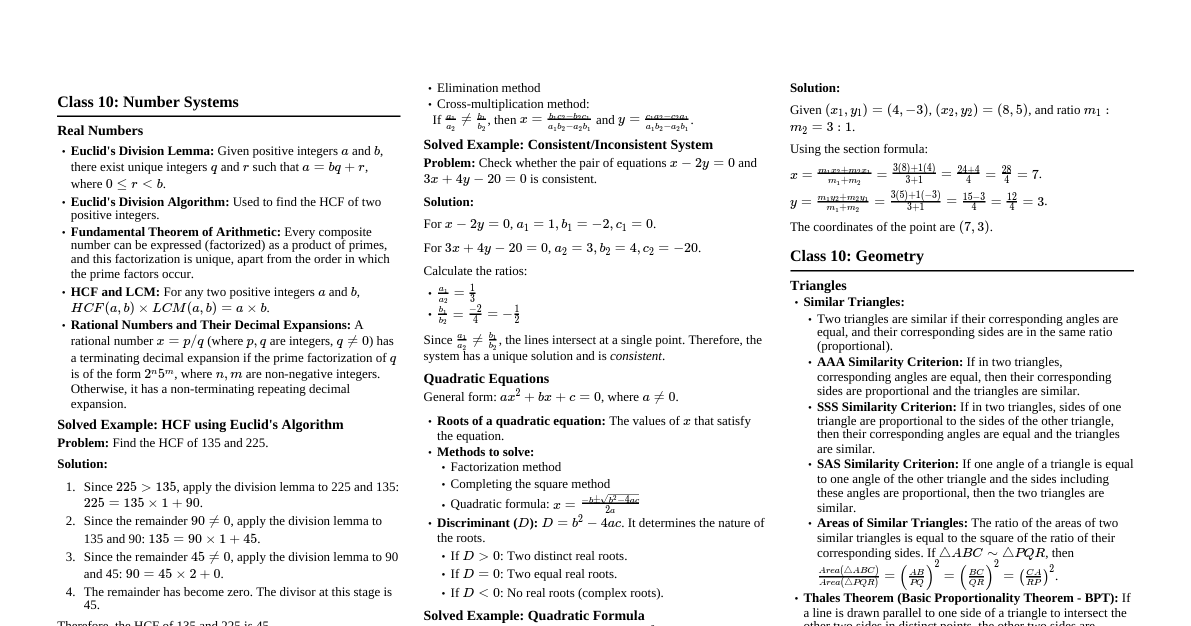

Ohm's Law Ohm's Law describes the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance in an electrical circuit. It states that the current through a conductor between two points is directly proportional to the voltage across the two points and inversely proportional to the resistance between them. Voltage (V): Measured in Volts (V). Represents the electrical potential difference. Current (I): Measured in Amperes (A). Represents the flow of electrical charge. Resistance (R): Measured in Ohms ($\Omega$). Represents the opposition to the flow of current. Formulas: The primary forms of Ohm's Law are: $V = I \cdot R$ (Voltage = Current $\times$ Resistance) $I = \frac{V}{R}$ (Current = Voltage / Resistance) $R = \frac{V}{I}$ (Resistance = Voltage / Current) These can be easily remembered using the Ohm's Law triangle: V I R Electrical Power Electrical power (P) is the rate at which electrical energy is converted to another form, such as heat, light, or mechanical energy. It is measured in Watts (W). Formulas: Power can be calculated using various combinations of voltage, current, and resistance: $P = V \cdot I$ (Power = Voltage $\times$ Current) $P = I^2 \cdot R$ (Power = Current$^2 \times$ Resistance) $P = \frac{V^2}{R}$ (Power = Voltage$^2$ / Resistance) These are derived by substituting Ohm's Law into the basic power formula $P=V \cdot I$. Resistors in Series and Parallel Resistors in Series: When resistors are connected in series, the total resistance is the sum of individual resistances. The current is the same through each resistor, but the voltage drops across each resistor add up to the total voltage. Total Resistance ($R_{total}$): $R_{total} = R_1 + R_2 + R_3 + \dots + R_n$ Current: $I_{total} = I_1 = I_2 = I_3 = \dots = I_n$ Voltage: $V_{total} = V_1 + V_2 + V_3 + \dots + V_n$ $R_1$ $R_2$ Resistors in Parallel: When resistors are connected in parallel, the reciprocal of the total resistance is the sum of the reciprocals of individual resistances. The voltage across each resistor is the same, but the currents through each branch add up to the total current. Total Resistance ($R_{total}$): $\frac{1}{R_{total}} = \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2} + \frac{1}{R_3} + \dots + \frac{1}{R_n}$ For two resistors: $R_{total} = \frac{R_1 \cdot R_2}{R_1 + R_2}$ Current: $I_{total} = I_1 + I_2 + I_3 + \dots + I_n$ Voltage: $V_{total} = V_1 = V_2 = V_3 = \dots = V_n$ $R_1$ $R_2$ Kirchhoff's Laws Kirchhoff's laws are fundamental to circuit analysis, especially for complex circuits that cannot be simplified using just series and parallel combinations. Kirchhoff's Current Law (KCL - Junction Rule): The algebraic sum of currents entering a node (or a closed boundary) is zero. In other words, the total current entering a junction must equal the total current leaving it. This is based on the conservation of charge. $$ \sum I_{in} = \sum I_{out} $$ Or equivalently: $$ \sum_{k=1}^n I_k = 0 $$ where $I_k$ is the current flowing into (positive) or out of (negative) the node. $I_1$ $I_2$ $I_3$ $I_4$ Kirchhoff's Voltage Law (KVL - Loop Rule): The algebraic sum of all voltages around any closed loop in a circuit is zero. This is based on the conservation of energy. $$ \sum_{k=1}^n V_k = 0 $$ where $V_k$ is the voltage drop (negative) or voltage rise (positive) across component $k$ in the loop. Steps for applying KVL: Assume a direction for current in each branch (if not already given). Choose a closed loop and a direction to traverse it (clockwise or counter-clockwise). As you traverse the loop: For a resistor: Voltage drop is $-IR$ if traversing in the direction of assumed current, or $+IR$ if traversing against the current. For a voltage source: Voltage rise is $+V$ if traversing from negative to positive terminal, or $-V$ if traversing from positive to negative terminal. Sum all voltage changes and set the sum to zero. Repeat for enough independent loops to solve the circuit. Capacitors A capacitor is a passive two-terminal electrical component that stores electrical energy in an electric field. It consists of two conductive plates separated by a dielectric material. Key Relationships: Charge (Q): $Q = C \cdot V$ (Charge = Capacitance $\times$ Voltage) Capacitance (C): Measured in Farads (F). Represents the ability to store charge. Energy Stored (E): $E = \frac{1}{2} C V^2 = \frac{1}{2} Q V = \frac{1}{2} \frac{Q^2}{C}$ Current-Voltage Relationship (DC): In a DC steady state, a capacitor acts as an open circuit (no current flows through it). Current-Voltage Relationship (AC/Transient): $i(t) = C \frac{dv(t)}{dt}$ Capacitors in Series: When capacitors are in series, their reciprocals add up to the reciprocal of the total capacitance. The charge on each capacitor is the same. $$ \frac{1}{C_{total}} = \frac{1}{C_1} + \frac{1}{C_2} + \frac{1}{C_3} + \dots + \frac{1}{C_n} $$ For two capacitors: $C_{total} = \frac{C_1 C_2}{C_1 + C_2}$ Charge: $Q_{total} = Q_1 = Q_2 = Q_3 = \dots = Q_n$ Voltage: $V_{total} = V_1 + V_2 + V_3 + \dots + V_n$ Capacitors in Parallel: When capacitors are in parallel, their capacitances add up directly to the total capacitance. The voltage across each capacitor is the same. $$ C_{total} = C_1 + C_2 + C_3 + \dots + C_n $$ Charge: $Q_{total} = Q_1 + Q_2 + Q_3 + \dots + Q_n$ Voltage: $V_{total} = V_1 = V_2 = V_3 = \dots = V_n$ Inductors An inductor is a passive two-terminal electrical component that stores energy in a magnetic field when current flows through it. It typically consists of a coil of wire. Key Relationships: Inductance (L): Measured in Henries (H). Represents the ability to store energy in a magnetic field. Voltage-Current Relationship (DC): In a DC steady state, an inductor acts as a short circuit (zero voltage drop across it). Voltage-Current Relationship (AC/Transient): $v(t) = L \frac{di(t)}{dt}$ Energy Stored (E): $E = \frac{1}{2} L I^2$ Inductors in Series: When inductors are in series, their inductances add up directly to the total inductance. The current is the same through each inductor. $$ L_{total} = L_1 + L_2 + L_3 + \dots + L_n $$ Current: $I_{total} = I_1 = I_2 = I_3 = \dots = I_n$ Voltage: $V_{total} = V_1 + V_2 + V_3 + \dots + V_n$ Inductors in Parallel: When inductors are in parallel, their reciprocals add up to the reciprocal of the total inductance. The voltage across each inductor is the same. $$ \frac{1}{L_{total}} = \frac{1}{L_1} + \frac{1}{L_2} + \frac{1}{L_3} + \dots + \frac{1}{L_n} $$ For two inductors: $L_{total} = \frac{L_1 L_2}{L_1 + L_2}$ Current: $I_{total} = I_1 + I_2 + I_3 + \dots + I_n$ Voltage: $V_{total} = V_1 = V_2 = V_3 = \dots = V_n$ RC and RL Circuits (First-Order Circuits) These circuits contain a resistor and either a capacitor (RC) or an inductor (RL), exhibiting transient behavior when a voltage/current source is switched on/off. RC Circuit (Charging/Discharging): Time Constant ($\tau$): $\tau = R \cdot C$ (seconds) Charging Voltage across Capacitor: $V_C(t) = V_S (1 - e^{-t/\tau})$ (assuming initially uncharged) Discharging Voltage across Capacitor: $V_C(t) = V_0 e^{-t/\tau}$ (assuming initial voltage $V_0$) Current during Charging: $I_C(t) = \frac{V_S}{R} e^{-t/\tau}$ After 5 time constants ($5\tau$), the capacitor is considered fully charged/discharged. RL Circuit (Charging/Discharging): Time Constant ($\tau$): $\tau = \frac{L}{R}$ (seconds) Charging Current through Inductor: $I_L(t) = I_S (1 - e^{-t/\tau})$ (assuming initially zero current) Discharging Current through Inductor: $I_L(t) = I_0 e^{-t/\tau}$ (assuming initial current $I_0$) Voltage across Inductor during Charging: $V_L(t) = V_S e^{-t/\tau}$ After 5 time constants ($5\tau$), the inductor current is considered fully established/decayed. AC Circuits (Phasors) For AC circuits, voltages and currents are represented as phasors, which are complex numbers representing the amplitude and phase of sinusoidal waveforms. Voltage (time domain): $v(t) = V_m \cos(\omega t + \phi_V)$ Current (time domain): $i(t) = I_m \cos(\omega t + \phi_I)$ Voltage (phasor): $\mathbf{V} = V_m \angle \phi_V = V_m (\cos \phi_V + j \sin \phi_V)$ Current (phasor): $\mathbf{I} = I_m \angle \phi_I = I_m (\cos \phi_I + j \sin \phi_I)$ Angular Frequency: $\omega = 2\pi f$ (rad/s) Impedance (Z): Impedance is the complex equivalent of resistance in AC circuits. It relates phasor voltage to phasor current via Ohm's Law for AC: $\mathbf{V} = \mathbf{I} \cdot \mathbf{Z}$. Resistor (R): $\mathbf{Z}_R = R \angle 0^\circ = R$ Inductor (L): $\mathbf{Z}_L = j\omega L = \omega L \angle 90^\circ$ Capacitor (C): $\mathbf{Z}_C = \frac{1}{j\omega C} = -\frac{j}{\omega C} = \frac{1}{\omega C} \angle -90^\circ$ Total impedance in series: $\mathbf{Z}_{total} = \mathbf{Z}_1 + \mathbf{Z}_2 + \dots$ Total impedance in parallel: $\frac{1}{\mathbf{Z}_{total}} = \frac{1}{\mathbf{Z}_1} + \frac{1}{\mathbf{Z}_2} + \dots$ Admittance (Y): Admittance is the reciprocal of impedance: $\mathbf{Y} = \frac{1}{\mathbf{Z}}$. Measured in Siemens (S). Conductance (G): Real part of admittance. Susceptance (B): Imaginary part of admittance. $\mathbf{Y} = G + jB$ $\mathbf{Y}_R = \frac{1}{R}$ $\mathbf{Y}_L = \frac{1}{j\omega L} = -j\frac{1}{\omega L}$ $\mathbf{Y}_C = j\omega C$ AC Power: In AC circuits, power is more complex due to phase differences. Instantaneous Power: $p(t) = v(t)i(t)$ Average Power (Real Power, P): $P = V_{rms} I_{rms} \cos(\phi_V - \phi_I) = \frac{1}{2} V_m I_m \cos(\phi_V - \phi_I)$. Measured in Watts (W). $P = I_{rms}^2 R = \frac{V_{rms}^2}{R}$ (for resistive components) Reactive Power (Q): $Q = V_{rms} I_{rms} \sin(\phi_V - \phi_I) = \frac{1}{2} V_m I_m \sin(\phi_V - \phi_I)$. Measured in Volt-Ampere Reactive (VAR). $Q_L = I_{rms}^2 X_L = \frac{V_{rms}^2}{X_L}$ (for inductive load, $X_L = \omega L$) $Q_C = -I_{rms}^2 X_C = -\frac{V_{rms}^2}{X_C}$ (for capacitive load, $X_C = \frac{1}{\omega C}$) Apparent Power (S): $S = V_{rms} I_{rms} = \sqrt{P^2 + Q^2}$. Measured in Volt-Ampere (VA). Power Factor (PF): $PF = \cos(\phi_V - \phi_I) = \frac{P}{S}$. Ranges from 0 to 1. Complex Power ($\mathbf{S}$): $\mathbf{S} = \mathbf{V}_{rms} \mathbf{I}_{rms}^* = P + jQ$. $\mathbf{V}_{rms}$ and $\mathbf{I}_{rms}$ are RMS phasor values. $\mathbf{I}_{rms}^*$ is the complex conjugate of the RMS current phasor. RMS values: For a sinusoid $X_m \cos(\omega t + \phi)$, $X_{rms} = \frac{X_m}{\sqrt{2}}$. Thevenin and Norton Equivalents These theorems simplify complex linear circuits into a simpler equivalent circuit at two terminals. Thevenin's Theorem: Any linear two-terminal circuit can be replaced by an equivalent circuit consisting of a single voltage source ($V_{Th}$) in series with a single resistor ($R_{Th}$). $V_{Th}$ (Thevenin Voltage): The open-circuit voltage across the two terminals. $R_{Th}$ (Thevenin Resistance): The equivalent resistance looking into the two terminals with all independent voltage sources short-circuited and all independent current sources open-circuited. (Dependent sources remain active). Norton's Theorem: Any linear two-terminal circuit can be replaced by an equivalent circuit consisting of a single current source ($I_N$) in parallel with a single resistor ($R_N$). $I_N$ (Norton Current): The short-circuit current flowing between the two terminals. $R_N$ (Norton Resistance): Same as Thevenin resistance, $R_N = R_{Th}$. Conversion between Thevenin and Norton: $V_{Th} = I_N \cdot R_N$ $I_N = \frac{V_{Th}}{R_{Th}}$ Maximum Power Transfer Theorem For a given Thevenin equivalent circuit, maximum power is transferred from the source to a load resistor ($R_L$)