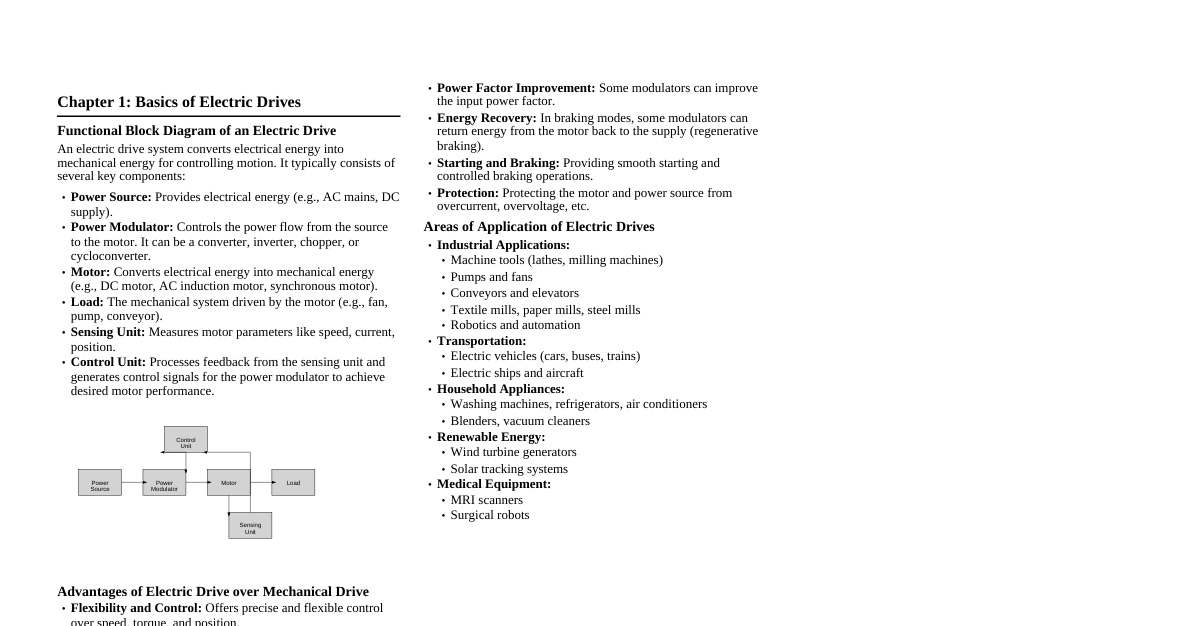

1. Steam Power Plant Working Principle Boiler: Water is heated to produce high-pressure steam. Turbine: Steam expands through the turbine, rotating its blades. Mechanical energy is converted to rotational energy. Generator: Turbine shaft is connected to a generator, which converts mechanical energy into electrical energy. Condenser: Exhaust steam from the turbine is condensed back into water, usually by cooling water, and then pumped back to the boiler. Block Diagram Boiler Turbine Generator Condenser Steam Mech Exhaust Feedwater Pump 2. Diesel Power Plant Layout and Working Fuel Storage: Diesel fuel is stored in tanks. Engine: Diesel engine burns fuel to produce mechanical energy. Generator: Engine drives a generator to produce electricity. Exhaust System: Discharges combustion gases. Cooling System: Maintains engine temperature. Starting System: For initial engine start-up. Working: Fuel is injected into the engine cylinders where it ignites due to high compression, pushing pistons. This linear motion is converted to rotational motion by the crankshaft, which then drives the generator. 3. Hydroelectric Power Plant Working Principle Converts potential energy of water stored at a height into kinetic energy, then into mechanical energy via a turbine, and finally into electrical energy via a generator. Schematic Diagram (simplified) Reservoir Penstock Turbine Gen Tailrace Mech Elect. 4. Nuclear Power Plant Construction and Working Reactor Core: Contains nuclear fuel (e.g., Uranium-235) where fission occurs, producing heat. Moderator: Slows down neutrons (e.g., heavy water, graphite). Control Rods: Absorb neutrons to control fission rate (e.g., Cadmium, Boron). Coolant: Transfers heat from the reactor (e.g., water, liquid sodium). Heat Exchanger/Steam Generator: Transfers heat from primary coolant to secondary water loop, producing steam. Steam Turbine, Generator, Condenser: Similar to a thermal power plant. Containment Building: Robust structure to prevent radiation leakage. Working: Nuclear fission in the reactor generates immense heat. This heat is transferred via a coolant to a steam generator, producing high-pressure steam. This steam drives a turbine connected to a generator to produce electricity. The steam is then condensed and returned to the steam generator. 5. Power Plant Comparison Feature Steam (Thermal) Diesel Hydro Nuclear Fuel Coal, Gas, Oil Diesel Oil Water Uranium Initial Cost High Moderate Very High Very High Running Cost High (fuel) High (fuel) Very Low Low (fuel) Efficiency 35-40% 30-45% 85-90% 30-40% Environmental Air pollution, CO$_2$ Air pollution, Noise Eco-friendly (dam impact) Radioactive waste, no CO$_2$ Flexibility Moderate High (quick start) High (load changes) Low (base load) 6. Nuclear Power: Safety & Impacts Safety Measures Containment Structure: Multiple barriers to prevent radiation release. Redundant Systems: Multiple backup systems for critical functions. Control Rods: Rapid shutdown (scram) capability. Emergency Core Cooling Systems (ECCS): To prevent meltdown. Waste Management: Secure storage and disposal of radioactive waste. Strict Regulations & Training: Continuous monitoring and highly trained personnel. Environmental Impacts Radioactive Waste: Long-term storage challenge. Thermal Pollution: Discharge of heated water into water bodies. No Greenhouse Gas Emissions: During operation (major advantage). Risk of Accidents: Though low, can have catastrophic consequences (e.g., Chernobyl, Fukushima). Uranium Mining: Environmental disturbance and potential radiation exposure. 7. Belt Drives Working Principles Transmit power between two shafts using an endless belt passing over pulleys. Power is transmitted due to the friction between the belt and pulley surfaces. Velocity Ratio Ratio of the speed of the driver to the speed of the driven pulley. $ \frac{N_2}{N_1} = \frac{d_1}{d_2} $ (for open belt drive, no slip) Where $N_1, N_2$ are speeds of driver and driven pulleys, $d_1, d_2$ are pitch diameters. Power Transmission $ P = (T_1 - T_2)v $ Where $T_1$ is tension in tight side, $T_2$ is tension in slack side, $v$ is belt velocity. Slip Relative motion between the belt and pulley surface. Reduces the velocity ratio and transmitted power. $ \text{Slip percentage} = \frac{N_1 d_1 - N_2 d_2}{N_1 d_1} \times 100 $ Creep Elastic phenomenon due to stretching of the belt on the tight side and contracting on the slack side. Also reduces the velocity ratio slightly, even without gross slip. 8. Rope Drives Working Principles and Applications Similar to belt drives but use ropes (fiber or wire) and grooved pulleys (sheaves). Suitable for transmitting large amounts of power over long distances. Applications: Cranes, hoists, textile machinery, power transmission over long distances, elevators. Better for shock absorption than belts. 9. Gear Drives Types of Gear Drives Transmit power between shafts by means of meshing teeth, ensuring positive drive without slip. Spur Gears: Teeth parallel to the axis, for parallel shafts. Simplest type. Helical Gears: Teeth cut at an angle to the axis, for parallel shafts. Smoother and quieter operation than spur gears. Bevel Gears: Conical shape, for intersecting shafts (usually at $90^\circ$). Worm Gears: Worm (screw-like) meshes with a worm wheel (gear). For non-intersecting, non-parallel shafts. High speed reduction, self-locking. Rack and Pinion: Converts rotary motion into linear motion. Rack is a straight gear, pinion is a circular gear. 10. Chain Drives Construction and Working Sprockets: Toothed wheels similar to gears. Chain: Series of interlinked pins and plates that engage with sprocket teeth. Working: The driver sprocket engages with the chain, pulling it and causing the driven sprocket to rotate. Provides a positive drive (no slip) and is suitable for moderate distances and heavy loads. Advantages, Disadvantages, Applications Advantages: Positive drive (no slip), higher efficiency than belts, compact, can transmit power over longer distances than gears, suitable for heavy loads. Disadvantages: More noise than belts, requires lubrication, wear on sprockets and chain, less flexible than belts for misalignment. Applications: Bicycles, motorcycles, industrial machinery (conveyors, agricultural equipment), timing chains in engines. Design & Selection Procedure Determine power to be transmitted, input/output speeds, and center distance. Select service factor based on load characteristics and prime mover type. Calculate design power ($P_d = P \times \text{Service Factor}$). Select chain type (e.g., roller chain) and pitch based on design power and speed. Determine number of teeth for sprockets, ensuring minimum teeth on smaller sprocket. Calculate chain length and adjust center distance if necessary. Check for lubrication requirements and potential chain sag. 11. Mechanical Power Transmission Comparison Feature Belt Drives Chain Drives Gear Drives Power Transmission Moderate Moderate to High High Speed Ratio Variable (slip) Fixed (no slip) Fixed (no slip) Efficiency 85-95% 95-98% 98-99% Cost Lowest Moderate Highest Shaft Distance Long Medium Short Noise Low Moderate Moderate to High Lubrication Not always Required Required Shock Absorption Good Fair Poor Selection Conditions Power to be transmitted: Determines robustness needed. Speed ratio: Fixed (gears, chains) vs. variable (belts with slip). Center distance: Short (gears), medium (chains), long (belts). Shaft alignment: Tolerances for misalignment. Operating environment: Dust, moisture, temperature. Cost and maintenance: Initial cost vs. running costs. Noise and vibration: Acceptable levels. Space availability: Compactness requirements. Positive drive requirement: If slip is unacceptable. Advantages & Disadvantages of Belt Drives vs. Others Advantages: Simple, economical, smooth operation, good shock absorption, can operate over long distances, protects against overload by slipping. Disadvantages: Slipping can occur (variable speed ratio), lower efficiency than chains/gears, limited power transmission for a given size, shorter life. 12. Robotics: Components & Joints Basic Components of a Robot A robot typically consists of: Manipulator (Arm): The mechanical structure that performs tasks. End-effector: The tool attached to the end of the manipulator (gripper, welder, etc.). Actuators: Motors (electric, hydraulic, pneumatic) that drive the joints. Sensors: Provide feedback about the robot's state and environment (position, force, vision). Controller: The "brain" that processes sensor data, executes programs, and commands actuators. Power Supply: Provides energy to the robot. Robot Joints and Movements Joints allow relative motion between links. They define the robot's degrees of freedom (DOF). Revolute (R) / Rotational Joint: Provides rotational motion about an axis. (e.g., shoulder, elbow). $1$ DOF. Prismatic (P) / Linear Joint: Provides linear motion along an axis. (e.g., sliding motion). $1$ DOF. Spherical (S) / Ball-and-Socket Joint: Provides 3 rotational DOFs (pitch, yaw, roll). Used for wrist. 13. Robot Links and Configurations Links in a Robotic Manipulator Links are the rigid bodies that make up the robot arm, connected by joints. Each link has a coordinate frame attached to it, used for kinematic analysis (Denavit-Hartenberg parameters). Base Link: The fixed part of the robot, usually connected to the ground. Intermediate Links: Connect the base to the end-effector. End-effector Link: The last link to which the tool is attached. Major Robot Configurations Classified by the arrangement of their joints (kinematics): Cartesian (Gantry/Rectangular): Uses three prismatic joints (PPP). Workspace: Rectangular. Applications: Pick-and-place, CNC machines, 3D printing. Cylindrical: One revolute and two prismatic joints (RPP). Workspace: Cylindrical. Applications: Assembly, machine loading, die casting. Spherical (Polar): Two revolute and one prismatic joint (RRP). Workspace: Spherical. Applications: Spot welding, machine tool loading. Articulated (Revolute/Jointed-Arm): All revolute joints (RRR or more). Most common industrial robot. Workspace: Large, complex. Applications: Arc welding, painting, assembly, material handling. SCARA (Selective Compliance Assembly Robot Arm): Two parallel revolute joints and one prismatic joint (RRPT). Workspace: Cylindrical, good for horizontal tasks. Applications: High-speed pick-and-place, assembly. Working of an Industrial Robot A typical industrial robot operates in a loop: Program Input: User defines tasks, waypoints, and actions. Controller Processing: Interprets the program, calculates joint angles required for desired end-effector position/orientation (inverse kinematics). Actuator Command: Controller sends signals to actuators (motors). Robot Movement: Actuators move the robot's joints and links. Sensor Feedback: Sensors (e.g., encoders for joint position, force sensors) provide real-time data on robot's actual state. Error Correction: Controller compares desired vs. actual state and adjusts actuator commands to minimize errors. End-effector Action: Tool performs the task (e.g., gripping, welding). Industrial Robot Diagram (Simplified Articulated Arm) Base Link 1 J1 Link 2 J2 Link 3 J3 Wrist End-effector Controller Power Sensors Actuators 14. Robotics: Applications & Sensors Applications of Robotics Manufacturing: Arc/spot welding, painting, assembly, material handling (pick-and-place), machine tending, quality inspection. Healthcare: Surgery (e.g., Da Vinci robot), rehabilitation, drug delivery, patient monitoring, prosthetics. Exploration: Space (Mars rovers), deep-sea, hazardous environments (nuclear inspection). Logistics: Automated guided vehicles (AGVs), warehouse automation, drone delivery. Service: Cleaning robots, security robots, domestic robots, entertainment. Agriculture: Harvesting, planting, spraying, livestock management. Role of Sensors in Robotics Sensors are crucial for robots to perceive their environment and their own state, enabling intelligent and adaptive behavior. Internal Sensors: Monitor robot's own state. Encoders/Resolvers: Measure joint position/angle. Force/Torque Sensors: Measure forces/torques exerted by/on the robot, enabling compliant motion. Accelerometers/Gyroscopes: Measure acceleration and angular velocity for orientation and motion control. External Sensors: Perceive the environment. Vision Sensors (Cameras): Object recognition, localization, inspection, guidance. Proximity Sensors: Detect presence of objects without contact (e.g., infrared, ultrasonic). Tactile Sensors: Detect contact and pressure. LIDAR/RADAR: Range finding, mapping, obstacle avoidance. Temperature Sensors: Monitor environmental or object temperature. 15. Robot End-Effectors & Future Trends Robot End-Effectors The "hand" or tool attached to the robot's wrist, designed for specific tasks. Types: Grippers: Mechanical (jaw-like), vacuum (suction cups), magnetic (for ferrous materials), adhesive. Used for grasping and holding objects. Tools: Welders (spot, arc), spray guns (painting), drills, grinders, cutters, assembly tools (screwdrivers), dispensers. Classification: Non-prehensile: Tools that act on objects (welder, spray gun). Prehensile: Grippers that grasp objects. Advantages, Disadvantages, and Future Trends in Robotics Advantages: Increased productivity and efficiency. Improved quality and precision. Safety (perform hazardous tasks). Consistency and repeatability. Reduced labor costs in some areas. Disadvantages: High initial cost. Requires skilled personnel for programming and maintenance. Lack of flexibility for highly variable tasks (traditional robots). Job displacement concerns. Safety risks in human-robot collaboration. Future Trends: Collaborative Robots (Cobots): Designed to work safely alongside humans. Artificial Intelligence (AI) & Machine Learning: Enhanced perception, decision-making, and learning capabilities. Cloud Robotics: Robots connected to cloud for data processing, learning, and sharing. Soft Robotics: Robots made from compliant materials, safer for interaction. Modular & Reconfigurable Robots: Easily adaptable for different tasks. Human-Robot Interaction (HRI): More intuitive interfaces and natural communication. Miniaturization & Nanorobotics: For micro-scale applications (e.g., medicine). Autonomous Mobile Robots (AMRs): Advanced navigation and decision-making for logistics and service.