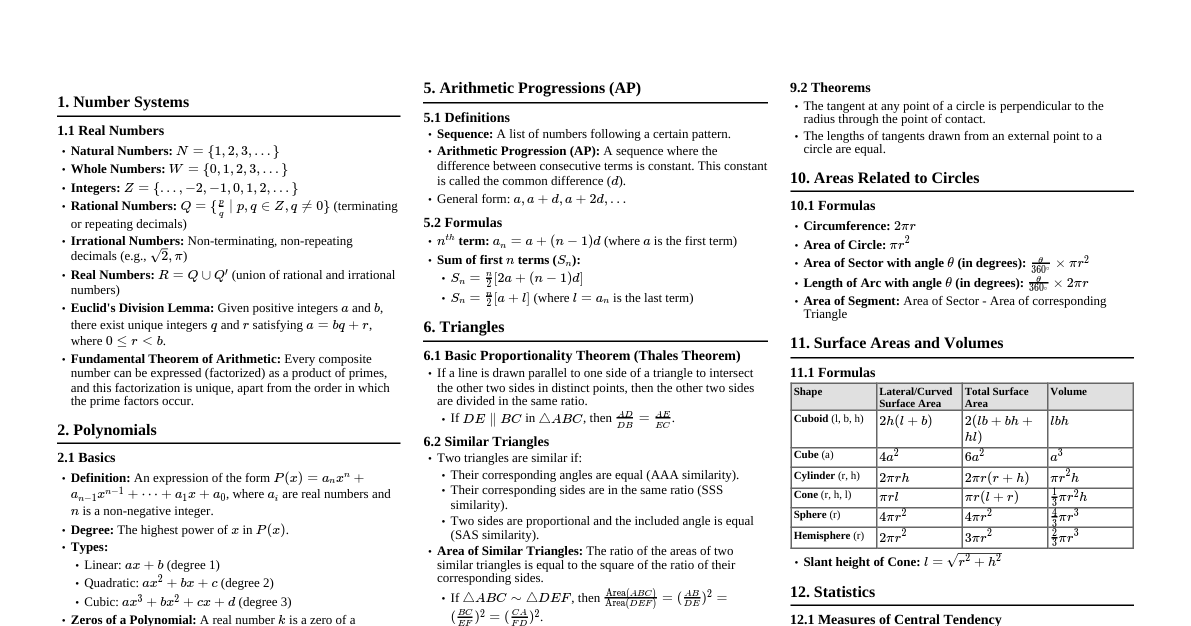

Patterns in Numbers & Shapes Patterns in Numbers: Sequences of numbers that follow a specific rule or logic. Arithmetic Progression: Each term is obtained by adding a fixed number (common difference) to the previous term. $a, a+d, a+2d, \dots$. Geometric Progression: Each term is obtained by multiplying the previous term by a fixed non-zero number (common ratio). $a, ar, ar^2, \dots$. Fibonacci Sequence: Each number is the sum of the two preceding ones, starting from $0$ and $1$. $0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, \dots$. Square Numbers: $1, 4, 9, 16, 25, \dots$ (perfect squares). Triangular Numbers: $1, 3, 6, 10, 15, \dots$ (sum of consecutive integers). Patterns in Shapes: Repetitive or symmetric arrangements of geometric figures. Tessellations: Patterns of shapes that fit together perfectly without any gaps or overlaps. Symmetry: Reflectional, rotational, and translational symmetry in shapes and designs. Fractals: Complex patterns that are self-similar across different scales. Growth Patterns: How shapes change or grow in a predictable manner (e.g., spirals in nature). Fundamentals of Arithmetics (Part 1) Number Systems Natural Numbers ($\mathbb{N}$): The counting numbers. $\{1, 2, 3, ...\}$. Sometimes defined to include zero: $\{0, 1, 2, 3, ...\}$. Properties: Closed under addition and multiplication. Whole Numbers ($\mathbb{W}$): Natural numbers including zero. $\{0, 1, 2, 3, ...\}$. Even Numbers: Integers that are exactly divisible by 2. Can be written as $2k$ for some integer $k$. E.g., $\dots, -4, -2, 0, 2, 4, \dots$. Odd Numbers: Integers that are not exactly divisible by 2. Can be written as $2k+1$ for some integer $k$. E.g., $\dots, -3, -1, 1, 3, 5, \dots$. Integers ($\mathbb{Z}$): All whole numbers and their negative counterparts. $\{\dots, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, \dots\}$. Properties: Closed under addition, subtraction, and multiplication. Rational Numbers ($\mathbb{Q}$): Numbers that can be expressed as a fraction $\frac{p}{q}$ where $p$ and $q$ are integers and $q \neq 0$. Examples: $1/2, -3/4, 5, 0.333\dots (1/3)$. Decimal Representation: Terminating or repeating decimals. Properties: Closed under addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division (by non-zero rational). Irrational Numbers: Numbers that cannot be expressed as a simple fraction. Their decimal representations are non-terminating and non-repeating. Examples: $\sqrt{2}, \pi, e$. Real Numbers ($\mathbb{R}$): All rational and irrational numbers. Represent all points on the number line. Fractions: A numerical quantity that is not an integer. Represents a part of a whole. Proper Fraction: Numerator Improper Fraction: Numerator $\ge$ Denominator (e.g., $3/2$). Mixed Number: An integer and a proper fraction (e.g., $1 \frac{1}{2}$). Basic Operations & Properties Addition ($+$): Combining quantities. Sum. Commutative Law: $a+b=b+a$. Associative Law: $(a+b)+c=a+(b+c)$. Identity Element: $0$ ($a+0=a$). Subtraction ($-$): Finding the difference between quantities. Not commutative or associative. Multiplication ($\times$ or $\cdot$): Repeated addition. Product. Commutative Law: $a \cdot b = b \cdot a$. Associative Law: $(a \cdot b) \cdot c = a \cdot (b \cdot c)$. Identity Element: $1$ ($a \cdot 1=a$). Zero Property: $a \cdot 0 = 0$. Division ($\div$ or $/$): Splitting into equal parts. Quotient. Not commutative or associative. Division by zero is undefined. Distributive Law: $a \cdot (b+c) = a \cdot b + a \cdot c$. Also $a \cdot (b-c) = a \cdot b - a \cdot c$. Inverse Elements: Additive Inverse: For any number $a$, there is $-a$ such that $a + (-a) = 0$. Multiplicative Inverse (Reciprocal): For any non-zero number $a$, there is $1/a$ such that $a \cdot (1/a) = 1$. Fundamentals of Arithmetics (Part 2) Exponentiation: $a^n$ (read as "$a$ to the power of $n$") means $a$ multiplied by itself $n$ times. $a$ is the base , $n$ is the exponent or power . Rules: $a^m \cdot a^n = a^{m+n}$, $(a^m)^n = a^{mn}$, $(ab)^n = a^n b^n$, $a^0=1$ ($a \neq 0$), $a^{-n} = 1/a^n$. Logarithms: The inverse operation to exponentiation. $\log_b x = y \iff b^y = x$. $b$ is the base , $x$ is the argument , $y$ is the logarithm . Common Logarithm: $\log_{10} x$. Natural Logarithm: $\ln x = \log_e x$. Rules: $\log_b (xy) = \log_b x + \log_b y$, $\log_b (x/y) = \log_b x - \log_b y$, $\log_b (x^k) = k \log_b x$, $\log_b b = 1$, $\log_b 1 = 0$. Change of Base: $\log_b x = \frac{\log_c x}{\log_c b}$. Number Theory Concepts Multiples: A multiple of an integer $n$ is any integer that can be divided by $n$ with no remainder. Formally, $kn$ for some integer $k$. Factors (Divisors): An integer $d$ is a factor of $n$ if $n/d$ is an integer. Prime Numbers: A natural number greater than 1 that has no positive divisors other than 1 and itself. Examples: $2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, \dots$. The number 2 is the only even prime number. Composite Numbers: A natural number greater than 1 that is not prime (i.e., has more than two positive divisors). Prime Factorization: The process of finding the prime numbers that multiply together to make a given number. Every composite number has a unique prime factorization (Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic). Example: $12 = 2 \times 2 \times 3 = 2^2 \times 3$. Number of Positive Divisors: If the prime factorization of $n$ is $p_1^{e_1} p_2^{e_2} \dots p_k^{e_k}$, then the total number of positive divisors is $(e_1+1)(e_2+1)\dots(e_k+1)$. Division Algorithm: For any integers $a$ (dividend) and $b$ (divisor) with $b > 0$, there exist unique integers $q$ (quotient) and $r$ (remainder) such that $a = bq + r$, where $0 \le r Fundamentals of Arithmetics (Part 3) Least Common Multiple (LCM): The smallest positive integer that is a multiple of two or more given integers. Method 1 (Listing Multiples): List multiples of each number until a common one is found. Method 2 (Prime Factorization): Find prime factorization of each number, then take the highest power of each prime factor. Relationship with GCD: For positive integers $a, b$, $\text{LCM}(a,b) \times \text{GCD}(a,b) = |a \times b|$. Greatest Common Divisor (GCD) / Highest Common Factor (HCF): The largest positive integer that divides each of two or more integers without leaving a remainder. Method 1 (Listing Factors): List factors of each number and find the largest common one. Method 2 (Prime Factorization): Find prime factorization of each number, then take the lowest power of each common prime factor. Method 3 (Euclidean Algorithm): An efficient algorithm for computing the GCD. Euclidean Algorithm on Numbers: Based on the principle that the GCD of two numbers does not change if the larger number is replaced by its difference with the smaller number. This process is repeated until one of the numbers is zero, and the GCD is the other number. More formally, $\text{gcd}(a,b) = \text{gcd}(b, a \pmod b)$ until $b=0$. Co-prime Numbers (Relatively Prime): Two integers $a$ and $b$ are co-prime if their greatest common divisor is 1. Example: $8$ and $15$ are co-prime ($\text{gcd}(8,15)=1$). Fundamentals of Arithmetics (Part 4) Modular Arithmetic Definition: A system of arithmetic for integers, where numbers "wrap around" after reaching a certain value—the modulus. $a \equiv b \pmod n$ (read as "$a$ is congruent to $b$ modulo $n$") means that $a$ and $b$ have the same remainder when divided by $n$. Equivalently, $n$ divides the difference $a-b$. The set of integers modulo $n$ is denoted $\mathbb{Z}_n = \{0, 1, 2, \dots, n-1\}$. Modular Addition: $(a+b) \pmod n = ((a \pmod n) + (b \pmod n)) \pmod n$. Modular Subtraction: $(a-b) \pmod n = ((a \pmod n) - (b \pmod n)) \pmod n$. Modular Multiplication: $(a \cdot b) \pmod n = ((a \pmod n) \cdot (b \pmod n)) \pmod n$. Modular Inverse: For an integer $a$, its modular multiplicative inverse modulo $n$ is an integer $x$ such that $ax \equiv 1 \pmod n$. An inverse exists if and only if $a$ and $n$ are co-prime ($\text{gcd}(a,n)=1$). Can be found using the Extended Euclidean Algorithm. Modular Exponentiation: Calculating $b^e \pmod m$ efficiently, especially for large exponents. Involves repeatedly squaring and multiplying. Divisibility Rules By 2: A number is divisible by 2 if its last digit is $0, 2, 4, 6,$ or $8$. By 3: A number is divisible by 3 if the sum of its digits is divisible by 3. By 4: A number is divisible by 4 if the number formed by its last two digits is divisible by 4. By 5: A number is divisible by 5 if its last digit is $0$ or $5$. By 6: A number is divisible by 6 if it is divisible by both 2 and 3. By 7: Double the last digit and subtract it from the remaining number. If the result is divisible by 7, the original number is too. (Repeat if necessary). By 8: A number is divisible by 8 if the number formed by its last three digits is divisible by 8. By 9: A number is divisible by 9 if the sum of its digits is divisible by 9. By 10: A number is divisible by 10 if its last digit is $0$. By 11: Find the alternating sum of the digits (subtract the second from the first, add the third, etc.). If this sum is divisible by 11, the number is. Propositional Logic Proposition (Statement): A declarative sentence that is either true (T) or false (F), but not both. Examples: "The sky is blue." (True), "2 + 2 = 5." (False). Non-examples: "What time is it?" (Question), "Go home!" (Command). Simple Proposition (Atomic Proposition): A proposition that cannot be broken down into simpler propositions. Compound Proposition: Formed by combining simple propositions using logical connectives. Truth Table: A systematic way to display the truth values of a compound proposition for all possible combinations of truth values of its simple propositions. Logical Connectives (Operators): Negation ($\neg$ or $\sim$): "not $p$". $\neg p$ is true if $p$ is false, and false if $p$ is true. Conjunction ($\land$): "$p$ and $q$". $p \land q$ is true only if both $p$ and $q$ are true. Disjunction ($\lor$): "$p$ or $q$". $p \lor q$ is true if at least one of $p$ or $q$ is true (inclusive OR). Exclusive OR ($\oplus$ or XOR): "$p$ XOR $q$". $p \oplus q$ is true if exactly one of $p$ or $q$ is true. Implication ($\to$ or $\implies$): "$p$ implies $q$", "if $p$ then $q$". $p \to q$ is false only if $p$ is true and $q$ is false. ($p$ is hypothesis, $q$ is conclusion). Bi-implication ($\leftrightarrow$ or $\iff$): "$p$ if and only if $q$". $p \leftrightarrow q$ is true if $p$ and $q$ have the same truth value. Exclusive NOR ($\overline{\oplus}$ or XNOR): $p \overline{\oplus} q$ is true if $p$ and $q$ have the same truth value (equivalent to $p \leftrightarrow q$). Logical Equivalences & Laws Tautology: A compound proposition that is always true, regardless of the truth values of its simple propositions. (e.g., $p \lor \neg p$). Contradiction: A compound proposition that is always false. (e.g., $p \land \neg p$). Contingency: A compound proposition that is neither a tautology nor a contradiction (its truth value depends on the truth values of its components). Logical Equivalence ($\equiv$): Two propositions $P$ and $Q$ are logically equivalent if $P \leftrightarrow Q$ is a tautology (i.e., they always have the same truth value). De Morgan’s Laws: $\neg(p \land q) \equiv \neg p \lor \neg q$. $\neg(p \lor q) \equiv \neg p \land \neg q$. Idempotent Laws: $p \lor p \equiv p$; $p \land p \equiv p$. Identity Laws: $p \lor F \equiv p$; $p \land T \equiv p$ (where $T$ is true, $F$ is false). Domination Laws: $p \lor T \equiv T$; $p \land F \equiv F$. Negation Laws: $p \lor \neg p \equiv T$; $p \land \neg p \equiv F$. Commutative Laws: $p \lor q \equiv q \lor p$; $p \land q \equiv q \land p$. Associative Laws: $(p \lor q) \lor r \equiv p \lor (q \lor r)$; $(p \land q) \land r \equiv p \land (q \land r)$. Distributive Laws: $p \lor (q \land r) \equiv (p \lor q) \land (p \lor r)$; $p \land (q \lor r) \equiv (p \land q) \lor (p \land r)$. Double Negation: $\neg(\neg p) \equiv p$. Absorption Laws: $p \lor (p \land q) \equiv p$; $p \land (p \lor q) \equiv p$. Dual of a Compound Proposition: Obtained by replacing $\land$ with $\lor$, $\lor$ with $\land$, $T$ with $F$, and $F$ with $T$. Predicate Logic and Quantifiers Predicate: A property or characteristic that describes a variable or a relationship among variables. It becomes a proposition when values are assigned to the variables. Example: $P(x)$ means "$x$ is an even number". $P(4)$ is true, $P(3)$ is false. Quantifiers: Symbols used to specify the quantity of elements in the domain that satisfy a predicate. Universal Quantifier ($\forall$): "for all", "for every", "for each". $\forall x P(x)$: The predicate $P(x)$ is true for every element $x$ in the domain. Existential Quantifier ($\exists$): "there exists", "for some", "for at least one". $\exists x P(x)$: There is at least one element $x$ in the domain for which $P(x)$ is true. Uniqueness Quantifier ($\exists!$ or $\exists_1$): "there exists a unique". $\exists! x P(x)$: There is exactly one element $x$ in the domain for which $P(x)$ is true. Scope of Quantifiers: The part of a logical expression to which the quantifier applies. Nested Quantifiers: Multiple quantifiers used in a single statement. The order often matters. Example: $\forall x \exists y P(x,y)$ (for every $x$, there exists a $y$ such that $P(x,y)$ is true). Example: $\exists y \forall x P(x,y)$ (there exists a $y$ such that for every $x$, $P(x,y)$ is true). These generally have different meanings. Negation of Quantified Statements: $\neg(\forall x P(x)) \equiv \exists x \neg P(x)$ (It's not true that all $x$ have property $P$ means there exists an $x$ that does not have property $P$). $\neg(\exists x P(x)) \equiv \forall x \neg P(x)$ (It's not true that there exists an $x$ with property $P$ means all $x$ do not have property $P$). Set Theory (Part 1) Set: A well-defined collection of distinct objects, called elements or members. The order of elements does not matter, and elements are not repeated. Notations: Set Roaster Form (Listing Method): Listing all elements of the set within curly braces. E.g., $A = \{1, 2, 3\}$. Set Builder Notation: Describing the properties that elements must satisfy to be in the set. E.g., $A = \{x \mid x \text{ is an even integer}\}$. Cardinality ($|A|$ or $n(A)$): The number of distinct elements in a set. Types of Sets: Empty Set ($\emptyset$ or $\{\}$): A set containing no elements. Its cardinality is $0$. Singleton Set: A set containing exactly one element. E.g., $\{5\}$. Finite Set: A set with a definite, countable number of elements (its cardinality is a natural number). Infinite Set: A set whose cardinality is not a natural number (e.g., $\mathbb{N}, \mathbb{Z}, \mathbb{R}$). Relationships Between Sets: Equivalent Sets: Two sets $A$ and $B$ are equivalent if they have the same cardinality ($|A|=|B|$). They can be put into one-to-one correspondence. Equal Sets ($A=B$): Two sets are equal if they contain exactly the same elements. Disjoint Sets: Two sets are disjoint if they have no common elements ($A \cap B = \emptyset$). Subset ($\subseteq$): $A \subseteq B$ if every element of $A$ is also an element of $B$. ($A$ is contained in $B$). Proper Subset ($\subset$): $A \subset B$ if $A \subseteq B$ and $A \neq B$ (i.e., $B$ contains at least one element not in $A$). Improper Subset: Every set is an improper subset of itself ($A \subseteq A$). Superset ($\supseteq$): If $A \subseteq B$, then $B$ is a superset of $A$. Power Set ($\mathcal{P}(A)$ or $2^A$): The set of all possible subsets of $A$. If $|A|=n$, then $|\mathcal{P}(A)|=2^n$. Set Operations Universal Set ($U$): The set of all possible elements under consideration. Intersection ($\cap$): $A \cap B = \{x \mid x \in A \text{ and } x \in B\}$. Elements common to both sets. Union ($\cup$): $A \cup B = \{x \mid x \in A \text{ or } x \in B\}$. Elements in either set (or both). Complement ($A'$ or $A^c$ or $\overline{A}$): The set of all elements in the universal set $U$ that are not in $A$. $A^c = \{x \mid x \in U \text{ and } x \notin A\}$. Set Difference ($-$ or $\setminus$): $A - B = \{x \mid x \in A \text{ and } x \notin B\}$. Elements in $A$ but not in $B$. Symmetric Difference ($\Delta$ or $\oplus$): $A \Delta B = (A-B) \cup (B-A)$. Elements that are in either $A$ or $B$ but not in their intersection. Also, $A \Delta B = (A \cup B) - (A \cap B)$. Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion (PIE): Used to find the cardinality of the union of sets. For two sets: $|A \cup B| = |A| + |B| - |A \cap B|$. For three sets: $|A \cup B \cup C| = |A|+|B|+|C| - (|A \cap B| + |A \cap C| + |B \cap C|) + |A \cap B \cap C|$. De Morgan’s Laws on Sets: $(A \cup B)^c = A^c \cap B^c$. $(A \cap B)^c = A^c \cup B^c$. Set Theory (Part 2) Cartesian Product ($A \times B$): The set of all possible ordered pairs $(a,b)$ where $a \in A$ and $b \in B$. If $|A|=m$ and $|B|=n$, then $|A \times B|=mn$. Example: If $A=\{1,2\}$, $B=\{x,y\}$, then $A \times B = \{(1,x), (1,y), (2,x), (2,y)\}$. Relation on Sets: A subset of the Cartesian product of two sets. If $R \subseteq A \times B$, then $R$ is a relation from $A$ to $B$. If $R \subseteq A \times A$, then $R$ is a relation on $A$. Types of Relations: Empty Relation: $R = \emptyset$. No elements are related. Universal Relation: $R = A \times B$. All elements are related. Identity Relation ($I_A$): A relation on set $A$ where $I_A = \{(a,a) \mid a \in A\}$. Each element is related only to itself. Inverse Relation ($R^{-1}$): If $R$ is a relation from $A$ to $B$, then $R^{-1}$ is a relation from $B$ to $A$ defined as $R^{-1} = \{(b,a) \mid (a,b) \in R\}$. Properties of Relations (on a single set $A$) Reflexive: A relation $R$ on set $A$ is reflexive if $(a,a) \in R$ for all $a \in A$. (Every element is related to itself). Symmetric: A relation $R$ on set $A$ is symmetric if whenever $(a,b) \in R$, then $(b,a) \in R$. (If $a$ is related to $b$, then $b$ is related to $a$). Anti-symmetric: A relation $R$ on set $A$ is anti-symmetric if whenever $(a,b) \in R$ and $(b,a) \in R$, then $a=b$. (Distinct elements cannot be related in both directions). Transitive: A relation $R$ on set $A$ is transitive if whenever $(a,b) \in R$ and $(b,c) \in R$, then $(a,c) \in R$. (If $a$ is related to $b$ and $b$ to $c$, then $a$ is related to $c$). Equivalence Relation: A relation that is simultaneously reflexive, symmetric, and transitive. Equivalence relations partition a set into disjoint equivalence classes. Example: "is congruent to modulo $n$" on $\mathbb{Z}$. Partial Order Relation: A relation that is reflexive, anti-symmetric, and transitive. Example: "less than or equal to" ($\le$) on $\mathbb{Z}$. Proving Techniques Direct Proof: Method: Assume the hypothesis (antecedent) is true, and use definitions, axioms, previously proven theorems, and logical equivalences to directly show that the conclusion (consequent) must also be true. Structure: "Assume $P$. Since $P \implies Q_1$, and $Q_1 \implies Q_2$, ..., and $Q_k \implies R$, therefore $R$. Thus, $P \implies R$." Indirect Proof (Proof by Contraposition): Method: To prove an implication $P \to Q$, prove its contrapositive $\neg Q \to \neg P$. This is logically equivalent. Structure: "To prove $P \to Q$, we prove $\neg Q \to \neg P$. Assume $\neg Q$. ... [deductions] ... Therefore, $\neg P$. Since $\neg Q \to \neg P$ is true, $P \to Q$ must also be true." Proof by Contradiction: Method: To prove a proposition $P$, assume that $P$ is false (i.e., assume $\neg P$ is true). Then, show that this assumption leads to a contradiction (a statement that is always false, like $R \land \neg R$). Since a false premise implies anything, and we reached a contradiction, our initial assumption $\neg P$ must be false, meaning $P$ must be true. Structure: "Assume, for the sake of contradiction, that $\neg P$ is true. ... [deductions] ... This leads to a contradiction (e.g., $S \land \neg S$). Therefore, the assumption $\neg P$ must be false, so $P$ is true." Rules of Inference: Elementary logical arguments that allow us to deduce new propositions from existing ones. Modus Ponens: If $p \to q$ is true and $p$ is true, then $q$ is true. $[(p \to q) \land p] \to q$. Modus Tollens: If $p \to q$ is true and $\neg q$ is true, then $\neg p$ is true. $[(p \to q) \land \neg q] \to \neg p$. Hypothetical Syllogism: If $p \to q$ is true and $q \to r$ is true, then $p \to r$ is true. $[(p \to q) \land (q \to r)] \to (p \to r)$. Disjunctive Syllogism: If $p \lor q$ is true and $\neg p$ is true, then $q$ is true. $[(p \lor q) \land \neg p] \to q$. Addition: If $p$ is true, then $p \lor q$ is true. $p \to (p \lor q)$. Simplification: If $p \land q$ is true, then $p$ is true. $(p \land q) \to p$. Conjunction: If $p$ is true and $q$ is true, then $p \land q$ is true. $[p \land q] \to (p \land q)$. Resolution: If $p \lor q$ is true and $\neg p \lor r$ is true, then $q \lor r$ is true. $[(p \lor q) \land (\neg p \lor r)] \to (q \lor r)$. Functions Definition: A relation $f$ from a set $A$ (domain) to a set $B$ (codomain), denoted $f: A \to B$, such that every element in $A$ is assigned to exactly one element in $B$. For each $x \in A$, there is a unique $y \in B$ such that $(x,y) \in f$. We write $y=f(x)$. Domain ($A$): The set of all possible input values for the function. Codomain ($B$): The set of all possible output values that the function *could* produce. Range (Image): The set of all actual output values produced by the function. $Range(f) = \{f(x) \mid x \in A\}$. The range is always a subset of the codomain. Graph of a Function: The set of all ordered pairs $(x, f(x))$ where $x$ is in the domain. Inverse Function ($f^{-1}$): A function that "reverses" the action of $f$. If $f(x)=y$, then $f^{-1}(y)=x$. An inverse function exists if and only if the original function $f$ is bijective (both injective and surjective). The domain of $f^{-1}$ is the range of $f$, and the range of $f^{-1}$ is the domain of $f$. Operations on Functions: Given $f: A \to \mathbb{R}$ and $g: A \to \mathbb{R}$: Addition: $(f+g)(x) = f(x)+g(x)$. Subtraction: $(f-g)(x) = f(x)-g(x)$. Multiplication: $(f \cdot g)(x) = f(x) \cdot g(x)$. Division: $(f/g)(x) = f(x)/g(x)$ for $g(x) \neq 0$. Composition: For $f: B \to C$ and $g: A \to B$, the composite function $(f \circ g)(x) = f(g(x))$. The domain of $f \circ g$ is the domain of $g$. Types of Functions: Injective (One-to-one): A function $f: A \to B$ is injective if distinct elements in $A$ map to distinct elements in $B$. Formally, if $f(x_1)=f(x_2)$ then $x_1=x_2$. No two elements in the domain map to the same element in the codomain. Surjective (Onto): A function $f: A \to B$ is surjective if every element in the codomain $B$ is mapped to by at least one element from the domain $A$. Formally, for every $y \in B$, there exists an $x \in A$ such that $f(x)=y$. The range equals the codomain. Bijective (One-to-one correspondence): A function that is both injective and surjective. Bijective functions have inverse functions. Cardinality Cardinality of Sets: The concept of "how many" elements are in a set. For Finite Sets: The cardinality $|A|$ is simply the number of elements in the set. For Infinite Sets: This concept extends to comparing the "sizes" of infinite sets. Two sets have the same cardinality if there exists a bijection (one-to-one correspondence) between them. Countable Sets: A set is countable if it is finite or if it has the same cardinality as the set of natural numbers $\mathbb{N}$. This means its elements can be listed in a sequence, even if the sequence is infinite. Countably Infinite Sets: Sets that have the same cardinality as $\mathbb{N}$. Examples: The set of natural numbers ($\mathbb{N}$), integers ($\mathbb{Z}$), rational numbers ($\mathbb{Q}$). The cardinality of countably infinite sets is denoted by $\aleph_0$ (Aleph-null). So, $|\mathbb{N}| = |\mathbb{Z}| = |\mathbb{Q}| = \aleph_0$. Uncountable Sets: An infinite set that is not countable. It cannot be put into one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers. Examples: The set of real numbers ($\mathbb{R}$), the set of all subsets of $\mathbb{N}$ (power set of $\mathbb{N}$). The cardinality of the real numbers is denoted by $\mathfrak{c}$ (the cardinality of the continuum). It has been proven that $\aleph_0 Cantor's Diagonalization Argument is a famous proof demonstrating the uncountability of real numbers. Cardinality Hierarchy: $|\mathbb{N}| = \aleph_0 Mathematical Induction Principle of Mathematical Induction (PMI): A powerful proof technique used to prove that a statement $P(n)$ is true for all integers $n$ greater than or equal to some initial integer $n_0$. Base Case (Basis Step): Show that the statement $P(n_0)$ is true for the smallest value $n_0$ in the domain (usually $n_0=0$ or $n_0=1$). This establishes a starting point for the "chain reaction". Inductive Hypothesis: Assume that the statement $P(k)$ is true for an arbitrary integer $k \ge n_0$. This is the assumption that the chain reaction holds for some $k$. Inductive Step: Show that if $P(k)$ is true, then $P(k+1)$ must also be true. This demonstrates that if the chain reaction holds for $k$, it must also hold for $k+1$. Once these three steps are completed, the PMI allows us to conclude that $P(n)$ is true for all integers $n \ge n_0$. Strong Induction (Principle of Strong Mathematical Induction): A variation of mathematical induction. Base Case: Show that $P(n_0)$ is true (and sometimes $P(n_0+1), \dots, P(m)$ if needed for the inductive step). Inductive Hypothesis: Assume that $P(j)$ is true for all integers $j$ such that $n_0 \le j \le k$, where $k \ge n_0$. (Instead of assuming only $P(k)$, we assume all preceding statements are true). Inductive Step: Show that if $P(j)$ is true for all $j$ from $n_0$ to $k$, then $P(k+1)$ must also be true. Strong induction is often useful when the truth of $P(k+1)$ depends not just on $P(k)$, but on several previous terms (e.g., in recurrence relations like the Fibonacci sequence). Well-Ordering Principle: Every non-empty set of positive integers contains a least element. This principle is equivalent to both forms of mathematical induction. Combinatorics and Counting Combinatorics: The branch of mathematics dealing with combinations and permutations of objects and sets of objects. It's about counting arrangements, selections, and distributions. Counting Principles: Addition Principle (Sum Rule): If a task can be performed in $n_1$ ways OR $n_2$ ways (where these ways are mutually exclusive, meaning they cannot happen at the same time), then the total number of ways to perform the task is $n_1 + n_2$. Multiplication Principle (Product Rule): If a task consists of a sequence of $k$ choices, and the first choice can be made in $n_1$ ways, the second in $n_2$ ways, ..., and the $k$-th choice in $n_k$ ways, then the total number of ways to perform the task is $n_1 \times n_2 \times \dots \times n_k$. Pigeonhole Principle: If $n$ items are put into $m$ containers, with $n > m$, then at least one container must contain more than one item. Generalized Pigeonhole Principle: If $n$ objects are placed into $m$ boxes, then there is at least one box containing at least $\lceil n/m \rceil$ objects. Permutation and Combination Permutations: Arrangements of objects where the order of selection or arrangement matters. Permutation of distinct objects ($P(n,k)$ or $_nP_k$): The number of ways to arrange $k$ items selected from $n$ distinct items. Formula: $P(n,k) = \frac{n!}{(n-k)!}$. (Here, $n! = n \times (n-1) \times \dots \times 1$, and $0!=1$). Permutation of $n$ distinct objects (all at once): $n!$. Permutation of non-distinct objects: If there are $n$ objects where $n_1$ are identical of type 1, $n_2$ are identical of type 2, ..., $n_k$ are identical of type $k$ (and $n_1+n_2+\dots+n_k=n$), then the number of distinct permutations is $\frac{n!}{n_1! n_2! \dots n_k!}$. Linear Permutations: Arrangements of objects in a straight line. The standard $P(n,k)$ and $n!$ formulas apply. Circular Permutations: Arrangements of objects in a circle. For $n$ distinct objects, the number of circular permutations is $(n-1)!$ (because rotating the arrangement doesn't create a new one). If arrangements are considered the same if they can be flipped (e.g., necklaces), it's often $\frac{(n-1)!}{2}$. Combinations: Selections of objects where the order of selection does not matter. Combinations of distinct objects ($C(n,k)$ or $_nC_k$ or $\binom{n}{k}$): The number of ways to choose $k$ items from $n$ distinct items without regard to order. Formula: $\binom{n}{k} = \frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}$. Combinations of non-distinct objects (Combinations with Repetition / Stars and Bars): The number of ways to choose $k$ items from $n$ types of items, with repetition allowed. Formula: $\binom{n+k-1}{k}$ or $\binom{n+k-1}{n-1}$. This is often used for problems like distributing identical items into distinct bins. Geometric Shapes - Combinations: Problems involving counting specific geometric configurations (e.g., number of lines formed by $n$ points, number of triangles formed by $n$ points, number of diagonals in a polygon). Increasing Path Problem - Combinations: Counting the number of shortest paths on a grid from one point to another, where movement is restricted (e.g., only right or up). If moving from $(x_1, y_1)$ to $(x_2, y_2)$, the number of paths is $\binom{(x_2-x_1)+(y_2-y_1)}{x_2-x_1}$. Derangements ($D_n$ or $!n$): A permutation of $n$ objects such that no object ends up in its original position. Formula: $!n = n! \sum_{i=0}^n \frac{(-1)^i}{i!} = n! \left( \frac{1}{0!} - \frac{1}{1!} + \frac{1}{2!} - \dots + \frac{(-1)^n}{n!} \right)$. Approximately $!n \approx n!/e$. Binomial Theorem Binomial Theorem: Provides a formula for expanding binomials (expressions with two terms) raised to a positive integer power. $(x+y)^n = \sum_{k=0}^n \binom{n}{k} x^{n-k} y^k = \binom{n}{0}x^n + \binom{n}{1}x^{n-1}y + \binom{n}{2}x^{n-2}y^2 + \dots + \binom{n}{n}y^n$. Binomial Coefficients: The numbers $\binom{n}{k}$ in the expansion, which are exactly the combination values. Binomial Identities: Symmetry Identity: $\binom{n}{k} = \binom{n}{n-k}$. Pascal's Identity: $\binom{n}{k} = \binom{n-1}{k-1} + \binom{n-1}{k}$. Sum of Binomial Coefficients: $\sum_{k=0}^n \binom{n}{k} = 2^n$ (setting $x=1, y=1$ in the binomial theorem). Vandermonde's Identity: $\sum_{k=0}^r \binom{m}{k}\binom{n}{r-k} = \binom{m+n}{r}$. Pascal's Triangle: A triangular array where each number is the sum of the two numbers directly above it. The rows of Pascal's Triangle correspond to the binomial coefficients for increasing powers of $(x+y)$. The $n$-th row (starting from $n=0$) contains the coefficients $\binom{n}{0}, \binom{n}{1}, \dots, \binom{n}{n}$. Recursion and Recurrence Recursive Definitions: Defining an object (a sequence, a function, a set, or an algorithm) in terms of itself. It consists of a base case and a recursive step. Base Case: Defines the initial value(s) or condition(s) to stop the recursion. Recursive Step: Defines how to compute later values or elements from earlier ones. Recursively Defined Sets: A set defined by: A basis step: Specifies initial elements in the set. A recursive step: Gives a rule for forming new elements from those already in the set. An exclusion rule (sometimes implicit): States that nothing else is in the set. Example: The set of even numbers: Basis: $0 \in E$. Recursive: If $x \in E$, then $x+2 \in E$ and $x-2 \in E$. Recurrence Relations: An equation that expresses the $n$-th term of a sequence as a function of one or more preceding terms. Often accompanied by initial conditions (base cases). Example: Fibonacci sequence: $F_n = F_{n-1} + F_{n-2}$, with $F_0=0, F_1=1$. Linear Recurrence Relations: Recurrence relations where each term is a linear combination of previous terms. Homogeneous: $a_n = c_1 a_{n-1} + c_2 a_{n-2} + \dots + c_k a_{n-k}$. Non-homogeneous: $a_n = c_1 a_{n-1} + \dots + c_k a_{n-k} + f(n)$. Solving involves finding the characteristic equation (for homogeneous parts) and particular solutions (for non-homogeneous). Graph Theory Graph ($G=(V,E)$): A mathematical structure consisting of a set of vertices (or nodes) $V$ and a set of edges (or links) $E$ connecting pairs of vertices. Types of Graphs: Undirected Graph: Edges have no direction. If an edge connects $u$ and $v$, it's denoted as $\{u,v\}$ (or $(u,v)$ interchangeably, but implies no direction). Directed Graph (Digraph): Edges have a direction. An edge from $u$ to $v$ is an ordered pair $(u,v)$, meaning it goes from $u$ to $v$. Simple Graphs: Graphs that have no loops (edges connecting a vertex to itself) and no multiple edges between the same pair of vertices. Multigraph: Allows multiple edges between the same pair of vertices. Pseudograph: Allows loops and multiple edges. Terminology: Adjacent Vertices: Two vertices are adjacent if there is an edge connecting them. Degree of a Vertex ($\text{deg}(v)$): The number of edges incident to a vertex $v$. In directed graphs, in-degree and out-degree. Handshaking Lemma: In any undirected graph, the sum of the degrees of all vertices is equal to twice the number of edges: $\sum_{v \in V} \text{deg}(v) = 2|E|$. Subgraph: A graph $H=(V',E')$ is a subgraph of $G=(V,E)$ if $V' \subseteq V$ and $E' \subseteq E$. Representations of Graphs: Adjacency Matrix: An $n \times n$ matrix (where $n=|V|$) where $A_{ij}=1$ if there is an edge between vertex $i$ and vertex $j$, and $0$ otherwise. For weighted graphs, $A_{ij}$ can be the weight. Adjacency List: For each vertex, a list of its adjacent vertices. More space-efficient for sparse graphs. Special Graph Types: Complete Graph ($K_n$): A simple graph where every pair of distinct vertices is connected by a unique edge. $|E| = \binom{n}{2}$. Cycle Graph ($C_n$): A graph consisting of $n$ vertices connected in a cycle. Wheel Graph ($W_n$): A cycle graph $C_{n-1}$ with an additional central vertex connected to all vertices of $C_{n-1}$. Bipartite Graphs: A graph whose vertices can be divided into two disjoint and independent sets $U$ and $V$ such that every edge connects a vertex in $U$ to one in $V$. No edges within $U$ or $V$. Complete Bipartite Graph ($K_{m,n}$): A bipartite graph where every vertex in $U$ is connected to every vertex in $V$. Matchings - Graphs: A matching in an undirected graph is a set of edges where no two edges share a common vertex. Maximum Matching: A matching with the largest possible number of edges. Perfect Matching: A matching that covers all vertices in the graph. Isomorphism of Graphs: Two graphs $G_1=(V_1,E_1)$ and $G_2=(V_2,E_2)$ are isomorphic if there exists a bijection $f: V_1 \to V_2$ such that for any $u,v \in V_1$, $\{u,v\} \in E_1$ if and only if $\{f(u),f(v)\} \in E_2$. Essentially, they have the same structure, just possibly different labels. Connectivity - Graph Theory: Connected Graph: An undirected graph is connected if there is a path between every pair of distinct vertices. Connected Components: Maximal connected subgraphs. Strongly Connected (Digraphs): A directed graph is strongly connected if there is a directed path from $u$ to $v$ and from $v$ to $u$ for every pair of vertices $u,v$. Weakly Connected (Digraphs): A directed graph is weakly connected if its underlying undirected graph (ignoring edge directions) is connected. Paths - Graph Theory: A sequence of distinct vertices $v_0, v_1, \dots, v_k$ such that $(v_{i-1}, v_i)$ is an edge for all $i=1, \dots, k$. Length of a Path: The number of edges in the path. Simple Paths: A path in which all vertices (except possibly the first and last) are distinct. Cycles - Graph Theory: A path that starts and ends at the same vertex, with all other vertices distinct. (e.g., $v_0, v_1, \dots, v_k, v_0$ where $v_0, \dots, v_k$ are distinct). Euler Path: A path in an undirected graph that visits every edge exactly once. Exists if and only if the graph is connected and has at most two vertices of odd degree. Euler Circuit (Euler Tour): An Euler path that starts and ends at the same vertex. Exists if and only if the graph is connected and all vertices have even degree. Hamilton Path: A path that visits every vertex exactly once. (Does not need to use all edges). Hamilton Circuit (Hamiltonian Cycle): A Hamilton path that starts and ends at the same vertex. (Does not need to use all edges). Planar Graphs: A graph that can be drawn on a plane such that no edges cross each other (edges only intersect at vertices). Euler's Formula for Planar Graphs: For any connected planar graph with $V$ vertices, $E$ edges, and $F$ faces (regions), $V - E + F = 2$. Kuratowski's Theorem: A graph is planar if and only if it does not contain a subgraph that is a subdivision of $K_5$ (complete graph on 5 vertices) or $K_{3,3}$ (complete bipartite graph with 3 vertices in each partition). Graph Coloring: Assigning colors to vertices of a graph such that no two adjacent vertices have the same color. Chromatic Number ($\chi(G)$): The minimum number of colors required to properly color a graph $G$. Four Color Theorem: Any planar graph can be colored with at most four colors. Trees: A connected undirected graph that contains no simple circuits (cycles). A tree with $n$ vertices has exactly $n-1$ edges. Any two vertices in a tree are connected by a unique simple path. Rooted Tree: A tree in which one vertex has been designated as the root. Spanning Tree: A subgraph that is a tree and connects all the vertices of the original graph. Minimum Spanning Tree (MST): For a weighted graph, a spanning tree with the smallest possible total edge weight. (Algorithms: Prim's, Kruskal's). Questions Patterns in Numbers Q1: What is the next number in the sequence $1, 4, 9, 16, \dots$? Justify your answer. Fundamentals of Arithmetics (Part 1) Q2: Identify which of the following numbers are rational: $0.333\dots$, $\sqrt{2}$, $\frac{7}{1}$, $\pi$. Explain why each is or isn't rational. Fundamentals of Arithmetics (Part 2) Q3: Find the prime factorization of $720$. Based on this, how many positive divisors does $720$ have? Fundamentals of Arithmetics (Part 3) Q4: Use the Euclidean Algorithm to find the GCD of $105$ and $30$. Then, using the relationship between GCD and LCM, find their LCM. Fundamentals of Arithmetics (Part 4) Q5: Find the smallest positive integer $x$ such that $7x \equiv 1 \pmod{29}$. Show your work to find the modular inverse. Propositional Logic Q6: Construct a truth table for the compound proposition $(p \land q) \to (p \lor \neg q)$. Based on the truth table, state whether it is a tautology, contradiction, or contingency. Predicate Logic and Quantifiers Q7: Let $P(x)$ be "x is an even number" and $Q(x)$ be "x is a prime number". Express the following statement in predicate logic using quantifiers and determine its truth value over the domain of integers: "Every even number is prime." Set Theory (Part 1) Q8: Given universal set $U = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8\}$, $A = \{1, 2, 3, 4\}$, and $B = \{3, 4, 5, 6\}$, find $A \cup B$, $A \cap B$, $A - B$, $A^c$, and $A \Delta B$. What is the cardinality of the power set of $A$, $|\mathcal{P}(A)|$? Set Theory (Part 2) Q9: Let $A = \{1, 2, 3\}$. Define a relation $R$ on $A$ as $R = \{(1,1), (2,2), (3,3), (1,2), (2,1)\}$. Is $R$ an equivalence relation? Justify your answer by checking reflexivity, symmetry, and transitivity. If not, explain which property/properties fail. Proving Techniques Q10: Prove by direct proof that if $n$ is an even integer, then $n^2$ is also an even integer. Functions Q11: Let $f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ be defined by $f(x) = 2x+3$. Determine if $f$ is injective, surjective, or bijective. If it is bijective, find its inverse function $f^{-1}(x)$. Cardinality Q12: Explain, without constructing a full bijection, why the set of natural numbers ($\mathbb{N}$) and the set of all positive odd numbers ($O = \{1, 3, 5, \dots\}$) have the same cardinality. What is this cardinality called? Mathematical Induction Q13: Prove by mathematical induction that for all integers $n \ge 1$, the sum of the first $n$ positive integers is given by the formula $\sum_{i=1}^n i = \frac{n(n+1)}{2}$. Combinatorics and Counting Q14: A standard deck of 52 cards has 4 suits (hearts, diamonds, clubs, spades) and 13 ranks (A, 2, ..., 10, J, Q, K). How many different 5-card hands can be chosen from a standard deck? Binomial Theorem Q15: Find the coefficient of $x^2y^3$ in the expansion of $(3x-y)^5$. Recursion and Recurrence Q16: A sequence is defined by the recurrence relation $a_n = 5a_{n-1} - 6a_{n-2}$ for $n \ge 2$, with initial conditions $a_0 = 1$ and $a_1 = 2$. Calculate $a_2, a_3,$ and $a_4$. What type of recurrence relation is this? Graph Theory Q17: A connected planar graph has 6 vertices and 9 edges. How many faces does this graph have according to Euler's formula? Draw an example of such a graph.