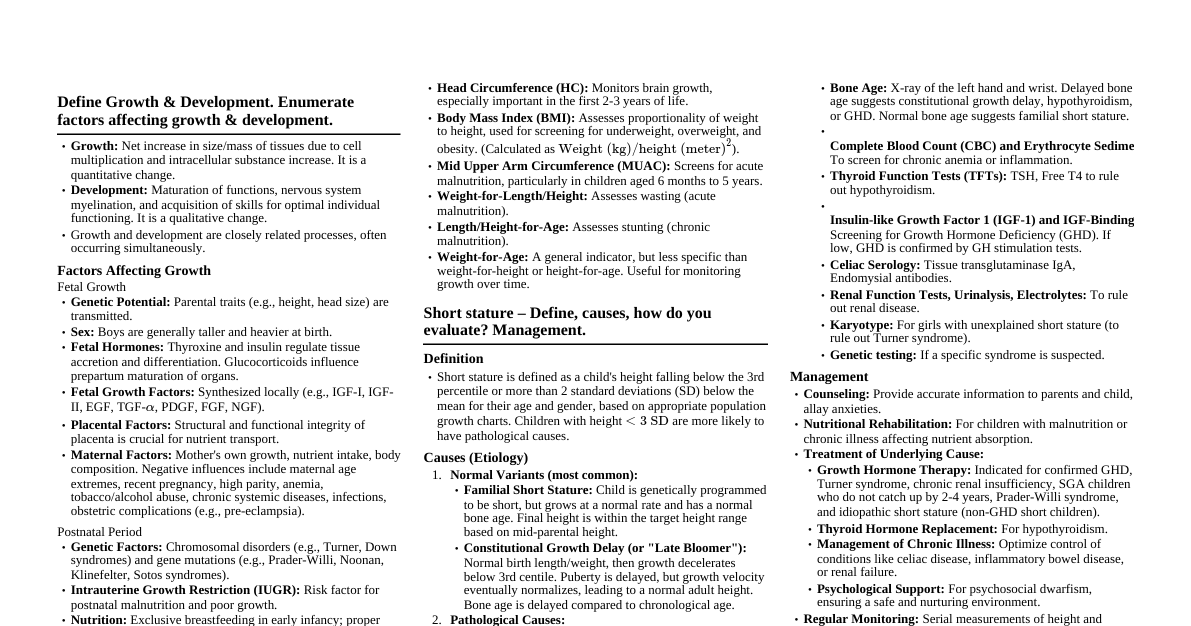

***** Define Growth & Development. Enumerate factors affecting growth & development. Growth: Net increase in size or mass of tissues, primarily due to cell multiplication and increase in intracellular substance. It refers to quantitative changes. Development: Maturation of functions and acquisition of skills. It refers to qualitative changes, related to nervous system myelination and acquisition of skills. Growth and development are closely related and usually proceed concurrently. Factors Affecting Growth Genetic Factors: Chromosomal disorders (e.g., Turner, Down syndrome) and single gene mutations (e.g., Prader-Willi, Noonan, Klinefelter, Sotos syndrome) can cause growth retardation or tall stature. Parental height significantly influences a child's potential height. Fetal Hormones: Thyroxine and insulin regulate tissue accretion and differentiation. Glucocorticoids influence prepartum maturation of organs. Fetal Growth Factors: Synthesized locally, act by autocrine and paracrine mechanisms (e.g., IGF-I, IGF-II, EGF, TGF-$\alpha$, PDGF, FGF). Placental Factors: Fetal weight correlates with placental weight; structural and functional changes in placenta adapt to increased needs. Maternal Factors (Prenatal): Mother's own growth, nutrient intake, body composition. Negative influences include teenage/advanced age, recent pregnancy, high parity, anemia, tobacco/drug/alcohol abuse, obstetric complications (e.g., PIH, pre-eclampsia), and chronic systemic diseases/infections. Nutrition (Postnatal): Protein-energy malnutrition, anemia, vitamin deficiencies retard growth. Calcium, iron, zinc, iodine, vitamins A and D are related to growth disorders. Hormonal Influence (Postnatal): Growth hormone and thyroxine crucial for normal development. Androgens and estrogens influence pubertal growth spurt and adult height. Infections: Common causes of poor growth in low-resource settings (diarrhea, respiratory infections, systemic infections, parasitic infestations). Chemical Agents: Androgenic hormones accelerate skeletal growth initially but cause premature epiphyseal closure. Trauma: Fracture near epiphysis can hamper skeletal growth. Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR): Risk factor for postnatal malnutrition and poor growth. Increases odds of underweight, stunting, wasting in first 5 years. Sex: Boys generally taller and heavier at birth; girls have earlier pubertal growth spurt. Factors Affecting Development Hereditary Potential: Genetic makeup influences developmental patterns and predispositions (e.g., parental IQ correlation, chromosomal abnormalities like Down syndrome). Biological Integrity: Absence of congenital anomalies, healthy organ systems, and proper neurological development are crucial. Physical Environment: Access to proper nutrition, clean water, safe housing, and absence of environmental toxins (e.g., lead, mercury). Psychosocial Environment: Parenting: Cognitive stimulation, caregiver sensitivity/affection, responsiveness, parental attitudes/involvement/education. Poverty: Major risk factor, leading to lack of stimulation, malnutrition, environmental toxins, and increased disease burden. Lack of Stimulation: Emotional deprivation and insufficient interaction. Violence/Abuse: Domestic or community violence can profoundly affect psychological and cognitive development. Maternal Depression: Negatively impacts early child development and parenting quality. Institutionalization: Increases risk of poor growth, ill-health, attachment disorders, and cognitive issues. Maternal Factors (Prenatal): Maternal malnutrition, exposure to drugs/toxins (alcohol, antiepileptics), and infections (syphilis, rubella, CMV) during pregnancy. Neonatal Risk Factors: IUGR, prematurity (especially $ Postnatal Nutrition: Severe calorie deficiency (stunting), iron deficiency, and iodine deficiency negatively impact brain development and cognitive function. Infectious Diseases: Chronic or severe infections (diarrhea, malaria, HIV) can lead to poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes. Acquired Insults to Brain: Traumatic brain injuries, meningitis, encephalitis. Sensory Impairments: Vision or hearing deficits can significantly impact milestone attainment. *** Age independent Anthropometric indices in children. Weight-for-Height (or Length-for-Weight in infants): This index assesses current nutritional status and body proportionality. It is independent of age for children under 5 years and helps identify wasting (acute malnutrition) or overweight/obesity. Body Mass Index (BMI)-for-Age: While BMI depends on age charts for interpretation, the calculation of BMI ($kg/m^2$) itself is age-independent. It's then plotted against age-specific charts to classify nutritional status (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese). Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC): MUAC is relatively stable between 6 months and 5 years of age, making it a useful age-independent screening tool for acute malnutrition, especially in community settings. A MUAC $ Head Circumference-for-Age: While head circumference is age-dependent for interpretation, the head circumference itself is a measurement. It is often used to assess brain growth and is less affected by acute nutritional changes than weight or height. *** Name anthropometric parameters for growth assessment. Weight: Total body mass. Length (for children Measured supine from head to heel. Height (for children $\ge 2$ years): Measured standing from head to heel. Head Circumference (HC): Measurement around the largest part of the head. Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC): Circumference of the arm at the midpoint between the acromion and olecranon. Chest Circumference: Measured at nipple level. Body Mass Index (BMI): Calculated as weight (kg) / height (m)$^2$. ***** Short stature – Define, causes, how do you evaluate? Management. Definition Short Stature: Height below the 3rd centile or $>2$ standard deviations (SD) below the median for age and gender. Height $ Causes of Short Stature Category Causes Physiological Short Stature or Normal Variant Familial, Constitutional Pathological Undernutrition Chronic systemic illness Cerebral palsy, Congenital heart disease, cystic fibrosis, asthma, Malabsorption (e.g., celiac disease), chronic liver disease, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, other chronic infections Endocrine causes Growth hormone deficiency, insensitivity, Hypothyroidism, Cushing syndrome, Pseudohypoparathyroidism, Precocious or delayed puberty Psychosocial dwarfism Children born small for gestational age Skeletal dysplasias Achondroplasia, rickets Genetic syndromes Turner, Down syndrome Evaluation of Short Stature Accurate Height Measurement: Supine length for children $ Standing height for older children (using a stadiometer). Assessment of Height Velocity: Plot serial measurements on a growth chart to determine the rate of growth (cm/year). A persistently low height velocity ( Comparison with Population Norms: Plot the child's height on standard growth charts (centile or SD score). Height below the 3rd centile or $-2$ SD is considered short stature. Comparison with Genetic Potential (Mid-Parental Height - MPH): For boys: $MPH = (\text{Mother's height} + \text{Father's height} + 13 \text{ cm}) / 2$ For girls: $MPH = (\text{Mother's height} + \text{Father's height} - 13 \text{ cm}) / 2$ Or, for boys: $MPH = (\text{Mother's height} + \text{Father's height}) / 2 + 6.5 \text{ cm}$ For girls: $MPH = (\text{Mother's height} + \text{Father's height}) / 2 - 6.5 \text{ cm}$ The child's height should generally fall within $\pm 8.5$ cm of the MPH. Assessment of Body Proportion: Upper segment (US) to lower segment (LS) ratio. Arm span compared to height. Disproportionate short stature suggests skeletal dysplasia or hypothyroidism. Sexual Maturity Rating (SMR): Assessed using Tanner staging in older children and adolescents. Bone Age Assessment: Radiograph of the left hand and wrist (for children 1-13 years) or knee for younger children. Compares skeletal maturity to chronological age. Delayed bone age is common in most pathological causes of short stature, except familial short stature (bone age = chronological age) and precocious puberty (bone age > chronological age). Detailed History: Clues to Etiology of Short Stature from History History Etiology Low birthweight Small for gestational age Polyuria Chronic renal failure, renal tubular acidosis Chronic diarrhea, greasy stools Malabsorption Neonatal hypoglycemia, jaundice, micropenis Hypopituitarism Headache, vomiting, visual problem Pituitary or hypothalamic space occupying lesion, e.g. cranio-pharyngioma Lethargy, constipation, weight gain Hypothyroidism Inadequate dietary intake Undernutrition Social history Psychosocial dwarfism Delayed puberty in parent(s) Constitutional delay of growth and puberty Physical Examination: Clues to Etiology of Short Stature from Examination Examination finding Etiology Disproportion Skeletal dysplasia, rickets, hypothyroidism Dysmorphism Congenital syndromes Pallor Chronic anemia, chronic renal failure Hypertension Chronic renal failure Frontal bossing, depressed nasal bridge, crowded teeth, small penis Hypopituitarism Goiter, coarse skin Hypothyroidism Central obesity, striae Cushing syndrome Laboratory Investigations (Stepwise approach): Level 1 (Essential) Complete hemogram with ESR. Urinalysis (microscopy, osmolality, pH). Stool examination (parasites, steatorrhea, occult blood). Blood tests: urea, creatinine, bicarbonate, pH, calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase, fasting glucose, albumin, transaminases. Level 2 (If indicated) Serum thyroxin (T4), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). Karyotype in all girls with unexplained short stature to rule out Turner syndrome. Level 3 (Specialized) Celiac serology (anti-endomysial, anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies). Provocative growth hormone testing (e.g., insulin tolerance test, clonidine stimulation test) if GHD suspected. Serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and IGF binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) levels. MRI brain (pituitary/hypothalamus) if growth hormone deficiency is confirmed. Management of Short Stature Counseling and Reassurance: For physiological causes (familial short stature, constitutional delay), parents need reassurance about the child's normal growth potential and final adult height. Nutritional Intervention: For undernutrition, dietary counseling and nutritional rehabilitation are essential. Specific micronutrient deficiencies should be corrected. Treatment of Underlying Chronic Illness: Managing conditions like celiac disease (gluten-free diet), chronic renal failure, or uncontrolled asthma can improve growth. Hormone Replacement Therapy: Hypothyroidism: Levothyroxine replacement. Growth Hormone Deficiency (GHD): Daily subcutaneous injections of recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH). Other indications for rhGH: Turner syndrome, children born SGA who fail to show catch-up growth, chronic renal failure (prior to transplant), Prader-Willi syndrome, Noonan syndrome, idiopathic short stature. Psychosocial Support: For psychosocial dwarfism, removing the child from the stressful environment and providing a nurturing home can lead to catch-up growth. Surgical Intervention: For severe skeletal dysplasias, limb lengthening procedures may be considered in specialized centers, but these are complex and have significant risks. Monitoring: Regular follow-up with growth measurements and monitoring of bone age are crucial to assess the effectiveness of interventions and track progress. ***A) LAWS OF GROWTH B) COMMON PATTERNS OF DEVELOPMENT A) Laws of Growth Continuous and Orderly Process: Growth is a continuous and orderly process, but it occurs with specific periods of acceleration and deceleration. Specific Growth Phases: Rapid fetal growth in the first half of gestation, which then slows until birth. High growth velocity in the early postnatal period (infancy), followed by a slower but steady rate during mid-childhood. A second accelerated growth phase occurs at puberty (pubertal growth spurt), followed by deceleration and cessation of growth as epiphyses fuse. Individual Growth Pattern: The growth pattern is unique to each individual, influenced by genetic potential and environmental factors. Cephalocaudal and Distal-to-Proximal Progression: Growth proceeds from head to toe (cephalocaudal) and from the center outwards (distal to proximal). For example, the head grows before the neck, and arms develop before legs, and hands before upper arms. Differential Growth Rates of Tissues: Different body tissues and systems grow at different rates and times: Brain Growth: Rapid during fetal and early postnatal life, reaching 90% of adult size by 2 years. Lymphoid Growth: Most notable during mid-childhood, often appearing larger than in mature adults. Gonadal Growth: Dormant during childhood, becoming prominent during puberty. Body Fat and Muscle Mass: Lean body mass (muscle, organs, skeleton) increases with stature, with boys typically having more lean body mass post-puberty. Body fat is an energy store. B) Common Patterns of Development Continuous and Orderly Process: Development is a continuous and orderly process, from conception to maturity, reflecting the maturation and myelination of the nervous system. Predictable Sequence: The sequence of milestone attainment is the same in all children (e.g., babbling before words, sitting before standing), although the exact timing may vary. Cephalocaudal Progression: Development proceeds from head to toe. For example, a child gains head control before trunk control, and arm control before leg control. Proximal-to-Distal Progression: Development proceeds from the center of the body outwards. For example, control over the shoulders and arms develops before control over the hands and fingers. Mass to Specific Activity: Initial disorganized, generalized mass activity is gradually replaced by specific, willful actions. For example, an infant initially moves their whole body to reach for an object, but later develops a precise grasp. Primitive Reflexes Integration: Primitive reflexes (e.g., palmar grasp, rooting reflex) must be lost or integrated into higher cortical control before the child can attain the corresponding voluntary developmental milestones. Differentiation and Integration: Development involves a process of differentiation (simple to complex) and integration (combining simpler skills into more complex ones). Asynchronous Development: Different developmental domains (gross motor, fine motor, language, personal-social) may progress at different rates within the same child. *****GROWTH CHARTS Definition: Growth charts are graphical tools used to track a child's physical growth (weight, length/height, head circumference, BMI) over time, comparing it to a reference population of healthy children. Purpose: Monitoring Growth: Detects deviations from normal growth patterns early. Screening for Growth Disorders: Identifies children who are underweight, stunted, wasted, overweight, obese, or have micro/macrocephaly. Assessing Nutritional Status: Helps diagnose malnutrition or overnutrition. Evaluating Interventions: Tracks the effectiveness of nutritional or medical interventions. Counseling: Provides a visual aid for discussions with parents about their child's growth. Types of Charts: WHO Growth Standards (0-5 years): Based on healthy, breastfed children from diverse ethnic backgrounds. Considered the international standard. CDC Growth Charts (2-20 years): Developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for older children and adolescents. Country-Specific Charts: Some countries develop their own charts using local reference populations. Parameters Plotted: Weight-for-age Length/Height-for-age Weight-for-length/height Body Mass Index (BMI)-for-age Head Circumference-for-age Interpretation: Centiles: Lines on the chart representing the percentage of children in the reference population who are at or below a certain measurement (e.g., 50th centile means 50% of children are smaller). Normal range is usually between the 3rd and 97th centiles. Z-scores (Standard Deviation Scores): Express how many standard deviations an individual's measurement is from the mean of the reference population. $Z = (\text{Observed value} - \text{Mean value}) / \text{Standard deviation}$. $\ge -2$ SD to $\le +2$ SD: Normal range. $ $>+2$ SD: Overweight (weight-for-height), Tall stature (height-for-age), Macrocephaly (HC-for-age). A child whose growth line crosses two major centile lines (e.g., from 50th to 10th or 97th to 75th) warrants further investigation, even if still within the normal range. Key Principles: Serial measurements are more informative than a single point. Growth velocity (rate of growth) is crucial. Plotting should be done accurately and consistently. Corrected age should be used for preterm infants until 2 years of age. ***** MICROCEPHALY – Define causes & management. Definition Microcephaly: Occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) greater than 3 standard deviations (SD) below the mean for age, sex, and gestational age. Some definitions use $>2$ SD below the mean, but this may include intellectually normal children. It implies an abnormally small brain (microencephaly). Causes of Microcephaly Category Causes Isolated microcephaly Autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant or X-linked Syndromic Trisomies 21, 18, 13, Monosomy 1p36 deletion, William, Cri-du-chat, Seckel, Smith Lemli Opitz, Cornelia de Lange, Rubinstein Taybi, Cockayne, Angelman Structural diseases Neural tube defects (anencephaly, hydranencephaly), Lissencephaly, schizencephaly, polymicrogyria Metabolic disorders Phenylketonuria, methylmalonic aciduria, citrullinemia, Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, Maternal (diabetes mellitus, untreated phenylketonuria) Infections Congenital (CMV, herpes simplex, rubella, varicella, toxoplasmosis, HIV), Meningitis Teratogens Alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, toluene, Antineoplastic agents, antiepileptic agents, Radiation Perinatal insult Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, hypoglycemia Endocrine Hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, adrenal insufficiency Management of Microcephaly Diagnosis and Etiology Identification: Thorough history (prenatal exposures, family history, developmental milestones). Physical examination (dysmorphic features, neurological deficits). Neuroimaging (MRI or CT scan of the brain) to assess brain structure and identify malformations or damage. Genetic testing (karyotyping, specific gene panels) if a syndromic or genetic cause is suspected. Infectious disease work-up (TORCH titers, Zika testing if indicated). Metabolic screening. No Specific Cure: There is no specific cure for microcephaly itself, as the brain size is already reduced or damaged. Management focuses on addressing the underlying cause (if treatable) and providing supportive care. Early Intervention and Supportive Care: Developmental Monitoring: Regular assessment of developmental milestones. Therapies: Physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy are crucial to maximize the child's developmental potential. Special Education: Children with microcephaly often have developmental delays or intellectual disabilities and require individualized educational plans. Management of Associated Conditions: Seizure Control: Antiepileptic drugs if seizures are present. Feeding Support: Addressing feeding difficulties, sometimes requiring gastrostomy tube placement. Sensory Impairments: Corrective lenses for vision problems, hearing aids for hearing loss. Behavioral Management: Strategies to address behavioral challenges. Genetic Counseling: For families with a genetic cause identified, genetic counseling is important to understand recurrence risks and options for future pregnancies. Parental Support: Providing information, emotional support, and connecting families to support groups. *** MACROCEPHALY- Define causes Definition Macrocephaly: Occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) greater than 2 standard deviations (SD) above the mean for age, sex, and gestational age. A rapidly increasing head circumference or crossing of centile lines is more concerning than an isolated measurement. Causes of Macrocephaly Category Causes Megalencephaly Benign familial, Neurocutaneous syndromes (Neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, Sturge-Weber), Sotos, Fragile X syndrome, Leukodystrophies (Alexander, Canavan), Lysosomal storage diseases (Tay-Sachs) Increased cerebrospinal fluid Hydrocephalus, benign enlargement of subarachnoid space, hydranencephaly, choroid plexus papilloma Enlarged vascular compartment Arteriovenous malformation Hemorrhage Subdural, epidural, subarachnoid or intraventricular Increase in bony compartment Bone disease (Achondroplasia, osteogenesis imperfecta, osteopetrosis), bone marrow expansion (Thalassemia major) Miscellaneous causes Intracranial mass lesions (Cyst, abscess or tumor), Raised intracranial pressure (Idiopathic pseudotumor cerebri, lead poisoning) ***** DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES till (read tables given in OP Ghai) (Gross motor, fine motor, social & adaptive, language) Key Gross Motor Developmental Milestones Age Milestone 3 mo Neck holding 5 mo Rolls over 6 mo Sits in tripod fashion (sitting with own support) 8 mo Sitting without support 9 mo Stands holding on (with support) 12 mo Creeps well; walks but falls; stands without support 15 mo Walks alone; creeps upstairs 18 mo Runs; explores drawers 2 yr Walks up and downstairs (2 feet/step); jumps 3 yr Rides tricycle; alternate feet going upstairs 4 yr Hops on one foot; alternate feet going downstairs Key Fine Motor Developmental Milestones Age Milestone 4 mo Bidextrous reach (reaching out for objects with both hands) 6 mo Unidextrous reach (reaching out for objects with one hand); transfers objects 9 mo Immature pincer grasp; probes with forefinger 12 mo Pincer grasp mature 15 mo Imitates scribbling; tower of 2 blocks 18 mo Scribbles; tower of 3 blocks 2 yr Tower of 6 blocks; vertical and circular stroke 3 yr Tower of 9 blocks; copies circle 4 yr Copies cross; bridge with blocks 5 yr Copies triangle; gate with blocks Key Social and Adaptive Milestones Age Milestone 2 mo Social smile (smile after being talked to) 3 mo Recognizes mother; anticipates feeds 6 mo Recognizes strangers, stranger anxiety 9 mo Waves "bye bye" 12 mo Comes when called; plays simple ball game 15 mo Jargon 18 mo Copies parents in task (e.g. sweeping) 2 yr Asks for food, drink, toilet; pulls people to show toys 3 yr Shares toys; knows full name and gender 4 yr Plays cooperatively in a group; goes to toilet alone 5 yr Helps in household tasks, dresses and undresses Key Language Milestones Age Milestone 1 mo Alerts to sound 3 mo Coos (musical vowel sounds) 4 mo Laugh loud 6 mo Monosyllables (ba, da, pa), ah-goo sounds 9 mo Bisyllables (mama, baba, dada) 12 mo 1-2 words with meaning 18 mo 8-10 word vocabulary 2 yr 2-3 word sentences, uses pronouns "I", "me", "you" 3 yr Asks questions; knows full name and gender 4 yr Says song or poem; tells stories 5 yr Asks meaning of words * Define Global Developmental delay. Global Developmental Delay (GDD): A significant delay in two or more developmental domains (e.g., gross motor, fine motor, speech/language, personal/social, cognition) in a child under the age of 5 years. The term "global" implies delays across multiple areas, suggesting a more widespread impact on neurological development. It is a provisional diagnosis used when a child is too young to undergo formal standardized intelligence testing. After age 5, if the child continues to show significant cognitive deficits, the diagnosis is often changed to intellectual disability. ***** BREATH HOLDING SPELLS & its treatment. Definition Breath-Holding Spells: Involuntary, non-epileptic events characterized by a specific sequence of crying, followed by apnea (cessation of breathing), often with cyanosis (blue discoloration) or pallor (paleness), leading to loss of consciousness, hypotonia, and sometimes a brief tonic-clonic seizure-like activity. They are a reflex response to a provocative event. Characteristics Age of Onset: Rare before 6 months, typically occur between 6 months and 6 years, with a peak incidence at 2 years. They usually resolve spontaneously by 5-6 years of age. Precipitating Factors: Usually triggered by anger, frustration, pain (e.g., after a fall), fear, or being startled. Types: Cyanotic Spells (most common): Child cries vigorously, then holds breath in expiration, becomes cyanotic, loses consciousness, and may become limp or stiff. Pallid Spells (less common): Child may cry briefly or not at all, becomes pale, loses consciousness quickly. Often triggered by pain or fright. Thought to be vagally mediated. Duration: Spells are typically brief, lasting from a few seconds to a minute. Post-event: After the spell, the child usually resumes normal breathing, may be drowsy or irritable, or may fall asleep. There is no post-ictal confusion typical of epilepsy. Differentiation from Seizures: Key differentiating features include the precipitating event, the characteristic sequence of crying-apnea-color change, and the absence of a true post-ictal state. Treatment and Management Reassurance and Education (Most Important): Educate parents that breath-holding spells are benign, self-limited, and do not cause brain damage or lead to epilepsy or death. Explain the physiological mechanism (involuntary reflex). Reduce parental anxiety, as their overreaction can reinforce the child's behavior. Behavioral Modification and Parental Strategies: Avoid Giving In: Do not give in to the child's demands or reinforce the behavior that triggers the spell. Consistency is key. Stay Calm: Parents should remain calm and avoid showing excessive alarm during a spell. Ensure Safety: During a spell, lay the child down on their side to prevent injury from falling or aspiration. Do not try to force breath or shake the child. Ignore the Tantrum: If the spell is part of a temper tantrum, ignore the tantrum itself (while ensuring safety). Distraction: Attempt to distract the child before a full spell develops. Positive Reinforcement: Praise and reward desirable behaviors. Time-Out: Can be used for associated temper tantrums, but not during the spell itself. Rule Out Underlying Causes: Iron Deficiency Anemia: A strong association exists, especially with cyanotic spells. All children with breath-holding spells should be screened for iron deficiency anemia (CBC, serum ferritin) and treated with iron supplementation if deficient. This is the only specific medical treatment often recommended. Cardiac Evaluation: For pallid spells, an ECG should be considered to rule out cardiac arrhythmias (e.g., prolonged QT syndrome), which can mimic pallid spells. Neurological Evaluation: If the presentation is atypical, or if there are concerns for seizures, a neurological consultation and EEG may be warranted. Pharmacological Treatment (Rarely Indicated): Anticonvulsants are generally not effective and not recommended as these are not true epileptic seizures. Atropine may be used in severe, frequent pallid spells under specialist guidance, but is rarely needed. Prognosis: The prognosis is excellent, with most children outgrowing the spells by school age without any long-term consequences. ***** Attention Deficit Hyperactivity (ADHD) – clinical features & management. Clinical Features of ADHD ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development. Symptoms must begin before age 12 years (DSM-5 criteria), be present for at least 6 months, occur in two or more settings (e.g., school and home), and clearly interfere with social, academic, or occupational functioning. Core Symptoms Categories: Examples of Inattentive and Hyperactive/Impulsive Behavior in ADHD Inattentive behavior Hyperactive behavior Impulsive behavior 1. Easily distracted by extraneous stimuli 1. Runs about or climbs excessively in situations where it is inappropriate 1. Difficulty awaiting turn in games or group situations 2. Often makes careless mistakes in schoolwork or other activities 2. Fidgets with hands and feet and squirms in seat 2. Blurts out answers to questions 3. Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play 3. Talks nonstop 3. Often interrupts conversations or others' activities 4. Often forgetful in daily activities 4. Has trouble sitting still during dinner, school, and story time 5. Does not seem to listen to what is being said to him 5. Has difficulty doing quiet tasks or activities. 6. Often fails to finish schoolwork or other chores 7. Daydreams, becomes easily confused, and move slowly 8. Difficulty in processing information as quickly and accurately as others Subtypes (DSM-5): Predominantly Inattentive Presentation: If enough inattention symptoms, but not enough hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms, were present for the past 6 months. Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation: If enough hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms, but not enough inattention symptoms, were present for the past 6 months. Combined Presentation: If enough symptoms of both inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity were present for the past 6 months (most common subtype). Management of ADHD ADHD management is multimodal, combining behavioral interventions, educational support, and often medication. Goals are to reduce symptoms, improve functioning, and enhance quality of life. 1. Behavioral Therapy and Parent Training: Parent Training in Behavior Management (PTBM): Teaches parents skills to reinforce positive behaviors, manage challenging behaviors, and create structured routines. It is the first-line treatment for preschool-aged children (4-5 years) with ADHD. Behavioral Classroom Management: Strategies for teachers to help children with ADHD succeed in school (e.g., clear rules, consistent consequences, positive reinforcement, preferential seating). Individual Behavioral Therapy: For older children and adolescents, focusing on organizational skills, problem-solving, and social skills. Family Therapy: To improve family communication and reduce conflict. 2. Medication: Medication is often the most effective treatment for reducing ADHD symptoms, especially for school-aged children and adolescents. Stimulants (First-line for school-aged children): Mechanism: Increase dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain. Examples: Methylphenidate (short-acting, intermediate-acting, long-acting), Amphetamine (short-acting, mixed salts, lisdexamfetamine). Effectiveness: Highly effective in 70-80% of individuals, reducing inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Side Effects: Decreased appetite, sleep problems, headache, stomachache, irritability, growth suppression (minor). Non-Stimulants: Examples: Atomoxetine, Guanfacine (extended-release), Clonidine (extended-release). Mechanism: Different mechanisms, often targeting norepinephrine. Use: Considered if stimulants are ineffective, not tolerated, or if there are co-occurring conditions (e.g., anxiety, tics). Side Effects: Atomoxetine (nausea, fatigue, dry mouth), Guanfacine/Clonidine (sedation, low blood pressure). 3. Educational Interventions: Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) or 504 Plans: Provide accommodations and specialized instruction in school. Academic Support: Tutoring, organizational skills training. 4. Lifestyle and Complementary Approaches: Healthy Diet: Balanced nutrition. Regular Physical Activity: Can help manage hyperactivity and improve focus. Adequate Sleep: Crucial for overall functioning. Mindfulness and Relaxation Techniques: May help some individuals. Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Some evidence suggests potential benefits, but not a primary treatment. Comprehensive Treatment Plan: A holistic approach involving pediatricians, psychiatrists, psychologists, teachers, and parents is essential. Treatment plans are individualized and periodically adjusted based on the child's response and evolving needs. Regular monitoring of symptoms, side effects of medication, and overall functioning is critical. ***** PICA. Definition Pica: A feeding disorder characterized by the persistent ingestion of non-nutritive, non-food substances for a period of at least 1 month. The behavior must be inappropriate for the child's developmental level (typically diagnosed in children >2 years old) and not be part of a culturally sanctioned practice. The ingestion must be severe enough to warrant clinical attention. Common Substances Ingested Dirt, clay, sand, pebbles, paint chips, plaster, hair, string, cloth, paper, ash, charcoal, soap, animal feces, ice (pagophagia). Predisposing Factors Developmental Delay/Intellectual Disability: Pica is more common in children with intellectual disabilities and autism spectrum disorder. Psychosocial Stressors: Neglect, lack of supervision, deprivation, poverty, family dysfunction. Nutritional Deficiencies: Iron Deficiency Anemia: A strong association, especially with geophagia (eating dirt) and pagophagia (eating ice). Zinc Deficiency: Also implicated. Other mineral deficiencies may play a role. Mental Health Conditions: Anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder. Pregnancy: Pica can occur in pregnant women. Risks and Complications Poisoning: Lead Poisoning: From ingesting paint chips (especially from old houses), plaster, or contaminated soil. This is a very serious complication leading to neurodevelopmental damage. Other toxic substances. Gastrointestinal Problems: Intestinal Obstruction: From ingesting foreign bodies (hairballs, stones). Perforation: Of the gastrointestinal tract. Constipation/Diarrhea: Parasitic Infestations: From ingesting contaminated soil or feces. Dental Injury: From chewing hard objects. Nutritional Deficiencies: Can be a cause or a consequence of pica. Bacterial Infections: From unhygienic substances. Management Diagnosis and Assessment: Detailed history of pica behaviors, duration, and substances ingested. Assessment of developmental level and psychosocial environment. Screening for nutritional deficiencies, especially iron and zinc (CBC, ferritin, zinc levels). Screening for lead poisoning (blood lead level) if paint or soil ingestion is suspected. Physical examination for signs of complications (e.g., abdominal tenderness, anemia). If obstruction is suspected, abdominal X-ray. Addressing Nutritional Deficiencies: If iron deficiency anemia is identified, treat with iron supplementation. This alone can sometimes resolve pica. Correct any other identified nutritional deficiencies. Environmental Modification and Safety: Remove access to the ingested substances (e.g., childproofing, ensuring a clean environment, inspecting play areas). Supervise the child closely. Behavioral Interventions: Positive Reinforcement: Reward the child for not engaging in pica and for appropriate play. Redirection: Redirect the child's attention to appropriate activities or chewable toys. Aversion Therapy: (Less common, used with caution) Applying a bad-tasting substance to the non-food item. Sensory Integration Therapy: If sensory needs are driving the pica. Psychosocial Support: Address any underlying psychosocial stressors, neglect, or lack of stimulation. Parent education and support. Medical Management of Complications: Treat lead poisoning (chelation therapy). Manage intestinal obstruction or parasitic infections. Dental care for damaged teeth. Multidisciplinary Approach: Involving pediatricians, nutritionists, developmental specialists, behavioral therapists, and social workers. ***** THUMB sucking. Description Thumb Sucking: A common self-comforting behavior in infants and young children, where the child habitually sucks their thumb or fingers. It is a normal and often beneficial behavior in infancy, providing comfort, security, and a means of self-regulation. Normal Development and Prevalence Onset: Often begins in utero or shortly after birth. Peak Incidence: Common in infants and toddlers, peaking around 18-21 months of age. Spontaneous Cessation: Most children spontaneously stop thumb sucking by 4-5 years of age, especially as they enter school and engage in more social activities. Distinction: Should be distinguished from "pathological" thumb sucking that persists into older childhood or causes significant problems. Causes and Triggers Self-soothing: Provides comfort, security, and helps manage anxiety, boredom, or tiredness. Hunger: Infants may suck their thumb when hungry. Exploration: Part of oral exploration in infants. Habit: Can become a strong habit. Concerns and Potential Problems (if persistent beyond 4-5 years) Dental Malocclusion: Prolonged and vigorous thumb sucking (especially after permanent teeth erupt) can lead to: Anterior open bite (front teeth don't meet). Protrusion of upper incisors. Retrusion of lower incisors. Narrowing of the upper dental arch. Speech Problems: Malocclusion can sometimes contribute to speech impediments. Skin Problems: Chapping, calluses, or infections on the thumb. Social Stigma: Older children may face teasing or social difficulties. Management Reassurance (for young children Parents should be reassured that thumb sucking in infants and toddlers is normal and usually resolves on its own. Advise parents to ignore the behavior, as drawing attention to it can sometimes reinforce it. Ensure the child receives adequate attention and comfort. Intervention (for older children >4-5 years or if dental/social issues arise): Motivation: The child must be motivated to stop. Involve them in the decision-making process. Identify Triggers: Help the child and parents identify when and why the child sucks their thumb (e.g., stress, boredom). Address underlying issues. Positive Reinforcement: Praise and reward the child for not sucking their thumb, especially during identified trigger times. Use a sticker chart or small rewards. Gentle Reminders: A gentle verbal reminder (e.g., "finger out") can be used, but avoid scolding or shaming. Substitution: Offer alternative comfort objects or activities, or a chewable toy. Physical Barriers: Applying a bitter-tasting but non-toxic substance (e.g., nail polish designed for thumb sucking cessation) to the thumb. Placing a bandage, glove, or a specific "thumb guard" device on the thumb. Dental Consultation: If dental problems are developing, consult an orthodontist. Dental appliances can be used as a physical barrier. Avoid Coercion: Forcing a child to stop can lead to psychological distress or simply shift the habit to another behavior. Address Underlying Anxiety: If thumb sucking is clearly linked to significant anxiety, psychological counseling may be beneficial. ***** List red flag signs & Clinical features of AUTISM Red Flag Signs for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Absence of Joint Attention: No babbling or gesturing (e.g., pointing, waving bye-bye) by 12 months. No pointing to show objects or share interest by 18 months. Lack of reciprocal social interaction (e.g., not sharing enjoyment with others by pointing or showing objects). Delayed or Absent Language Development: No single words by 16 months. No two-word meaningful phrases (not just echoing or repeating) by 24 months. Any loss of speech, babbling, or social skills at any age. Impaired Social Interaction: Poor or inconsistent eye contact. Lack of warm, joyful expressions (e.g., smiling when pleased). Lack of response to name by 12 months. Limited or absent imitation of others. Lack of interest in peers or difficulty making friends. Preference for solitary play. Repetitive Behaviors and Restricted Interests: Repetitive motor mannerisms (e.g., hand flapping, body rocking, spinning). Unusual or intense interest in parts of objects (e.g., spinning wheels of a toy car rather than playing with the car). Excessive adherence to routines or rituals; extreme distress at small changes. Unusual sensory interests or aversions (e.g., unusual reactions to sounds, textures, lights). Lack of Pretend Play: Absence of imaginative or "make-believe" play by 18-24 months. Clinical Features of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (DSM-5 Criteria) ASD is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. These symptoms must be present in the early developmental period and cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning. A. Persistent Deficits in Social Communication and Social Interaction (all three must be met): Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity: Ranging from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation. To reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect. To total lack of initiation of social interactions. Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction: Ranging from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication. To abnormalities in eye contact and body language. To deficits in understanding and use of gestures. To a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication. Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships: Ranging from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts. To difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends. To absence of interest in peers. B. Restricted, Repetitive Patterns of Behavior, Interests, or Activities (at least two of the following must be met): Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech: Simple motor stereotypies (e.g., hand flapping, finger posturing, rocking). Lining up toys or flipping objects. Echolalia (repeating words/phrases). Idiosyncratic phrases. Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior: Extreme distress at small changes. Difficulties with transitions. Rigid thinking patterns. Greeting rituals. Need to take the same route or eat the same food every day. Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus: Strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects. Excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests (e.g., an intense focus on trains, vacuum cleaners, or specific movie characters). Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interests in sensory aspects of the environment: Indifference to pain/temperature. Adverse response to specific sounds or textures. Excessive smelling or touching of objects. Visual fascination with lights or movement. *** Asymmetric tonic neck reflex. Definition Asymmetric Tonic Neck Reflex (ATNR), also known as the "fencing reflex": A primitive reflex observed in newborn infants. When the infant's head is turned to one side, the arm and leg on that side extend, while the arm and leg on the opposite side flex. Characteristics Trigger: Turning the infant's head to one side. Response: "Face" side: Arm and leg on the side the head is turned towards extend. "Skull" side: Arm and leg on the opposite side flex. Timing: Appearance: Present at birth. Integration: Normally integrates (disappears) by 4-6 months of age. Purpose: May play a role in developing unilateral body movements. Assists with eye-hand coordination in early stages. Prevents rolling over before the infant is neurologically ready. Clinical Significance Persistence beyond 6 months: If the ATNR persists beyond 6 months of age, it is considered abnormal and can be a "red flag" for neurological problems. It may indicate: Cerebral palsy. Other neurological impairments. Developmental delay. Interference with Development: A persistent ATNR can interfere with: Rolling over. Bringing hands to midline. Crawling (as the child cannot coordinate bilateral movements). Developing symmetrical posture and balance. Eye-hand coordination (difficulty tracking objects across the midline). Assessment: Neurological examination of infants includes checking for the presence and integration of primitive reflexes like the ATNR. *** Add a note on a) Temper Tantrum Definition: Behavioral outbursts by a child, typically in response to physical or emotional challenges, frustration, or a desire for attention or control. They often involve yelling, crying, screaming, kicking, hitting, biting, or throwing objects. Age: Most common between 18 months and 3 years (the "terrible twos"), peaking in the second and third years of life. They usually subside by 3-6 years of age. Causes: Frustration: Inability to communicate needs or desires effectively (limited language skills). Desire for Autonomy/Independence: As toddlers assert their will. Fatigue, Hunger, Overstimulation: Physical discomfort. Seeking Attention: If tantrums are rewarded with parental attention. Testing Limits: Learning about boundaries. Management: Prevention: Ensure child is well-rested and fed. Avoid known triggers. Offer choices to give a sense of control. Distract before a tantrum escalates. During Tantrum: Stay Calm: Parents should remain calm and avoid engaging in arguments. Ensure Safety: Remove the child from dangerous situations or remove dangerous objects from the child's reach. Ignore the Behavior: If the tantrum is for attention, ignoring it (while staying close for safety) is often effective. Time-Out: For older toddlers (typically 2+ years), a brief "time-out" (e.g., 1 minute per year of age) in a safe, boring place can be effective. After Tantrum: Reconnection: Once the child calms down, offer comfort and reassurance. Positive Reinforcement: Praise the child for calming down and for appropriate behavior. Teach Coping Skills: Help the child learn to express feelings verbally. When to Seek Help: Tantrums that are unusually violent, frequent, prolonged, or occur in older children (e.g., >4-5 years), or are associated with other behavioral problems, may warrant consultation with a pediatrician or child psychologist. b) Enuresis Definition: Repeated involuntary (or, rarely, intentional) urination into the bed or clothes. Age: Diagnosed when the child is at least 5 years old (or equivalent developmental level). It must occur at least twice a week for 3 consecutive months, or cause significant distress or impairment. Types: Nocturnal Enuresis: Occurs only during night sleep (bedwetting). Most common type. Diurnal Enuresis: Occurs during waking hours. Mixed Enuresis: Both nocturnal and diurnal. Primary Enuresis: Child has never achieved a period of sustained dryness (most cases). Secondary Enuresis: Child develops enuresis after having been dry for at least 6 months. Causes: Genetic Predisposition: Strong family history (75% if both parents had it, 40% if one parent). Delayed Bladder Maturation: Smaller functional bladder capacity or an inability to recognize bladder fullness during sleep. Nocturnal Polyuria: Reduced nocturnal secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), leading to increased urine production at night. Deep Sleep: Difficulty waking up to a full bladder. Constipation: A full rectum can press on the bladder and reduce its capacity. Psychological Stress: (More common in secondary enuresis) e.g., birth of a sibling, starting school, family conflict. Medical Conditions (rarely): Urinary tract infection (UTI), diabetes mellitus, spinal cord abnormalities, obstructive sleep apnea. Management: Reassurance: Enuresis is common and usually resolves spontaneously. It is not the child's fault. Behavioral Strategies (First-line): Fluid Restriction: Limit fluids 2 hours before bedtime. Scheduled Voiding: Encourage voiding before bedtime. Avoid Blame/Punishment: Focus on positive reinforcement. Bladder Training: For diurnal enuresis, encourage regular voiding and gradually increase time between voids. Enuresis Alarms: Highly effective for nocturnal enuresis. Wakes the child when urination begins, conditioning them to wake up. Pharmacological Treatment (for refractory cases or short-term use): Desmopressin (DDAVP): Synthetic ADH, reduces nocturnal urine production. Used for short-term events (e.g., sleepovers, camps) or as a temporary measure. Imipramine: A tricyclic antidepressant, mechanism unclear, but has anticholinergic effects and may reduce sleep depth. Used with caution due to potential side effects. Treat Underlying Conditions: Address constipation, UTIs, or other medical issues. Psychological Support: If significant stress or emotional issues are present. c) Encopresis Definition: Repeated voluntary or involuntary passage of feces into inappropriate places (e.g., underwear, floor). Age: Diagnosed when the child is at least 4 years old (or equivalent developmental level). It must occur at least once a month for 3 consecutive months, and not be due to a medical condition (other than constipation) or substance use. Types: With Constipation and Overflow Incontinence (most common, ~80-95%): Chronic constipation leads to fecal impaction. Liquid stool then leaks around the impaction, causing soiling. The child may not feel the urge to defecate due to rectal distention. Without Constipation and Overflow Incontinence: Less common, often associated with behavioral issues, oppositional defiance, or underlying psychological problems. Causes: Chronic Constipation: The primary cause of encopresis with overflow. Can be due to diet (low fiber), inadequate fluid intake, holding stool (due to painful defecation or fear of toilet), or medical conditions (e.g., Hirschsprung's disease, hypothyroidism, spinal cord lesions - less common). Painful Defecation: A cycle where painful bowel movements lead to stool retention, which worsens constipation and pain. Behavioral/Psychological Factors: Fear of toilets, power struggles with parents, stress, anxiety, or underlying developmental disorders (e.g., ADHD, autism). Delayed Toilet Training: Clinical Features: Soiling of underwear (often mistaken for diarrhea). Fecal odor. Avoidance of defecation, straining, or hiding soiled underwear. Symptoms of chronic constipation (e.g., infrequent, hard stools, abdominal pain, decreased appetite). Psychological distress, shame, social isolation. Management: Reassurance and Education: Explain to the child and parents that encopresis is not intentional and is a medical problem. Reduce shame and blame. Disimpaction: The first step is to clear the impacted stool from the colon. This usually involves high doses of oral laxatives (e.g., polyethylene glycol) or, in some cases, enemas. Maintenance Therapy: Laxatives: Continue daily laxatives (e.g., polyethylene glycol, lactulose) to ensure soft, easy-to-pass stools and prevent re-impaction. Gradually taper over months. Dietary Changes: Increase fiber and fluid intake. Behavioral Program (Toilet Training): Scheduled Toileting: Encourage regular, unhurried toilet sits (e.g., 5-10 minutes after meals) to establish a routine. Positive Reinforcement: Reward efforts and successes (e.g., sitting on the toilet, passing stool in the toilet) with praise and sticker charts. Avoid Punishment: Never punish the child for soiling. Psychological Support: If behavioral or emotional issues are prominent, or if the child is severely distressed, referral to a child psychologist or therapist. Treat Underlying Conditions: Rule out and treat any organic causes if suspected. Long-term Follow-up: Encopresis often requires long-term management (months to years) to prevent relapse.