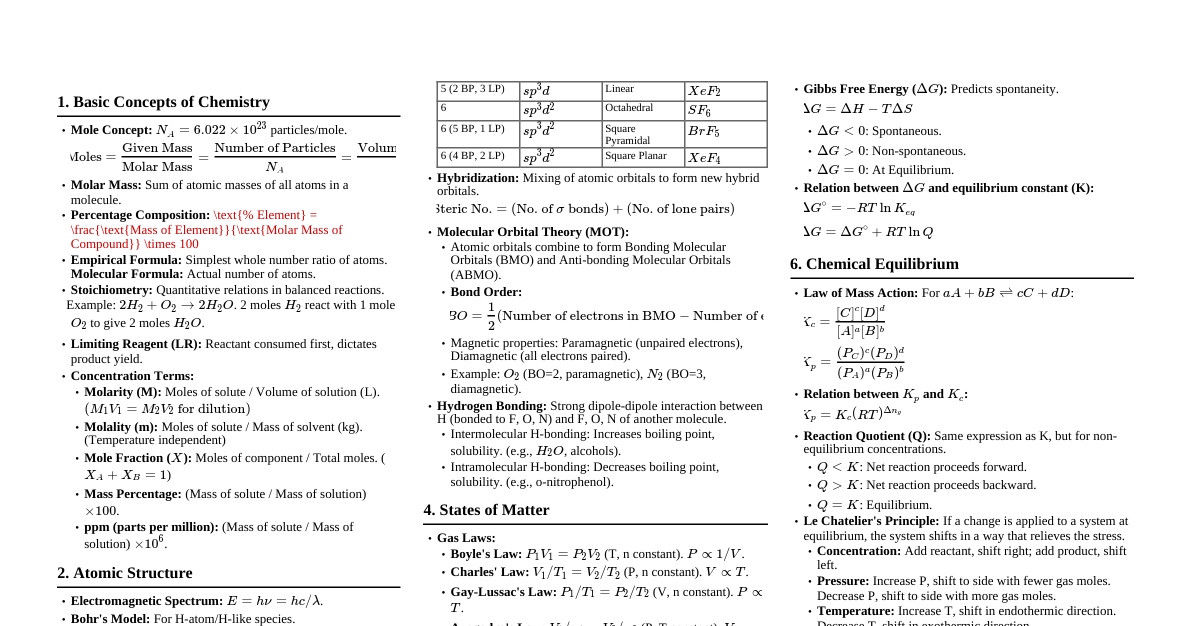

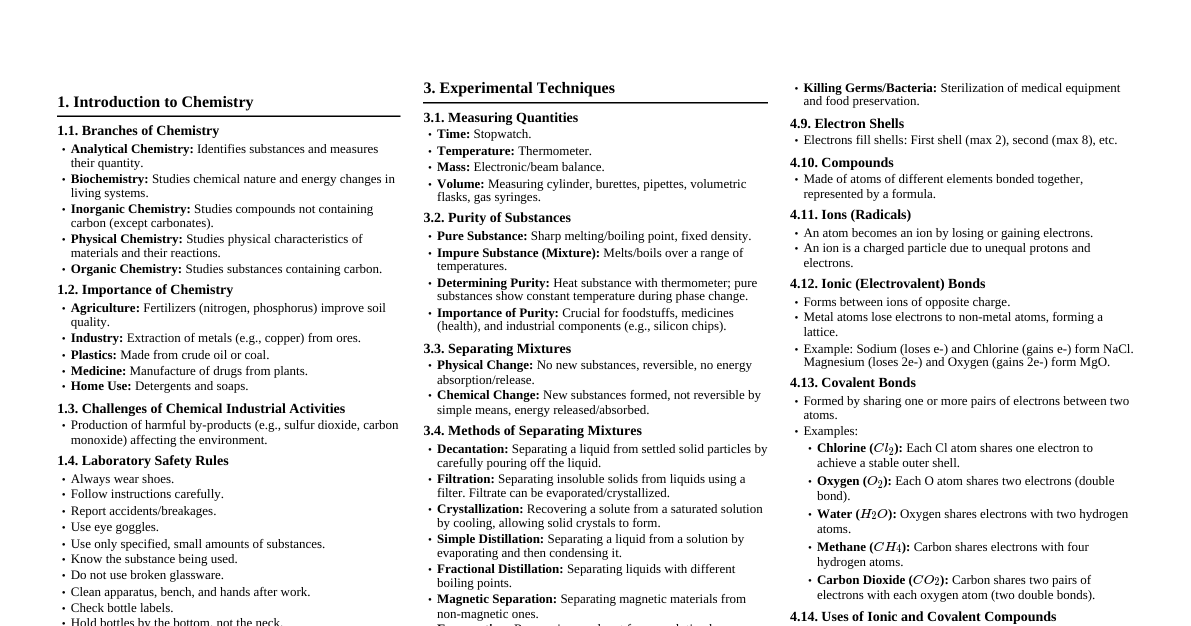

1. Foundation and Fundamentals Matter: Anything that has mass and occupies space. Pure Substances: Fixed composition, distinct properties. Elements: Cannot be broken down by chemical means (e.g., O, H, Fe). Compounds: Two or more elements chemically combined in fixed proportions (e.g., $H_2O$, $CO_2$). Mixtures: Two or more substances physically combined, variable composition. Homogeneous: Uniform composition throughout (e.g., salt water, air). Heterogeneous: Non-uniform composition; components are distinguishable (e.g., sand and water, oil and water). States of Matter: Solid: Definite shape and volume, particles tightly packed, vibrate in fixed positions. Liquid: Indefinite shape, definite volume, particles close but can move past each other. Gas: Indefinite shape and volume, particles far apart and move randomly. Plasma: Ionized gas, found in stars and lightning. Bose-Einstein Condensate: Occurs at extremely low temperatures, supercooled matter. Physical Changes: Do not alter the chemical composition (e.g., melting, boiling, dissolving). Chemical Changes: Result in new substances with different chemical compositions (e.g., burning, rusting). Laws of Chemical Combination: Law of Conservation of Mass (Antoine Lavoisier): In any chemical reaction, the total mass of the reactants is equal to the total mass of the products. Mass is neither created nor destroyed. Law of Definite Proportions (Joseph Proust): A given chemical compound always contains the same elements in the exact same proportions by mass, regardless of its source or method of preparation. (e.g., water ($H_2O$) always has a 1:8 mass ratio of H:O). Law of Multiple Proportions (John Dalton): When two elements combine to form more than one compound, the masses of one element that combine with a fixed mass of the other element are in ratios of small whole numbers. (e.g., C and O form CO and $CO_2$; for a fixed mass of C, the ratio of O masses is 1:2). 2. Stoichiometry 2.1 Dalton's Atomic Theory (1808) and its Postulates Matter is composed of indivisible particles called atoms. (Later found to be divisible into subatomic particles). Atoms of a given element are identical in mass and properties; atoms of different elements differ in mass and properties. (Isotopes and isobars disproved the identical mass part). Compounds are formed when atoms of different elements combine in simple whole-number ratios. A chemical reaction involves the rearrangement of atoms. Atoms are neither created nor destroyed during a chemical reaction. 2.2 Laws of Stoichiometry Stoichiometry is the quantitative relationship between reactants and products in chemical reactions, based on the Law of Conservation of Mass and the Law of Definite Proportions. Balanced chemical equations are essential for stoichiometric calculations. 2.3 Avogadro's Law and Some Deductions Avogadro's Law: Equal volumes of all gases, at the same temperature and pressure, have the same number of molecules. ($V \propto n$ at constant T, P). Avogadro's Number ($N_A$): The number of particles (atoms, molecules, ions) in one mole of any substance, approximately $6.022 \times 10^{23} \text{ particles/mol}$. 2.4 Mole Concept and its Relation with Mass, Volume, and Number of Particles Mole: The SI unit for the amount of substance. One mole contains $N_A$ elementary entities. Molar Mass (M): The mass of one mole of a substance, expressed in grams per mole (g/mol). Numerically equal to the atomic/molecular weight in amu. Relationship with Mass: $\text{mass (g)} = \text{moles} \times \text{molar mass (g/mol)}$ Relationship with Number of Particles: $\text{number of particles} = \text{moles} \times N_A$ Molar Volume (for gases at STP): At Standard Temperature and Pressure (STP: $0^\circ C$ or 273.15 K and 1 atm), one mole of any ideal gas occupies 22.4 liters. Relationship with Volume (for gases at STP): $\text{volume (L)} = \text{moles} \times 22.4 \text{ L/mol}$ 2.5 Limiting Reactant and Excess Reactant Limiting Reactant (or Limiting Reagent): The reactant that is completely consumed first in a chemical reaction. It determines the maximum amount of product that can be formed. Excess Reactant: The reactant(s) present in an amount greater than required to react completely with the limiting reactant. Some amount of the excess reactant will be left over after the reaction. 2.6 Theoretical Yield, Experimental Yield, and Percent Yield Theoretical Yield: The maximum amount of product that can be formed from a given amount of reactants, calculated using stoichiometry assuming 100% reaction efficiency. Experimental Yield (or Actual Yield): The amount of product actually obtained from a chemical reaction in the laboratory. It is usually less than the theoretical yield due to various factors (incomplete reactions, side reactions, loss during purification). Percent Yield: A measure of the efficiency of a reaction. $$ \text{Percent Yield} = \frac{\text{Experimental Yield}}{\text{Theoretical Yield}} \times 100\% $$ 2.7 Calculation of Empirical and Molecular Formula Empirical Formula: Represents the simplest whole-number ratio of atoms in a compound. Molecular Formula: Represents the actual number of atoms of each element in a molecule of the compound. Steps to determine Empirical Formula: Convert given percentages by mass to grams (assume 100 g sample). Convert grams of each element to moles using atomic masses. Divide all mole values by the smallest mole value to get a ratio. If ratios are not whole numbers, multiply by a small integer to get whole numbers. Steps to determine Molecular Formula: Calculate the empirical formula mass (sum of atomic masses in empirical formula). Determine the integer 'n' using the formula: $n = \frac{\text{Molecular Mass}}{\text{Empirical Formula Mass}}$. (Molecular mass must be given or determined experimentally). Multiply the subscripts in the empirical formula by 'n' to get the molecular formula. Molecular Formula = $(Empirical \ Formula)_n$. 3. Atomic Structure Subatomic Particles: Protons ($p^+$): Positively charged (+1 elementary charge), mass $\approx 1.007 \text{ amu}$ (or $1.672 \times 10^{-27} \text{ kg}$). Located in the nucleus. Neutrons ($n^0$): No charge (neutral), mass $\approx 1.009 \text{ amu}$ (or $1.675 \times 10^{-27} \text{ kg}$). Located in the nucleus. Electrons ($e^-$): Negatively charged (-1 elementary charge), negligible mass $\approx 0.00055 \text{ amu}$ (or $9.109 \times 10^{-31} \text{ kg}$). Orbit the nucleus in electron shells/orbitals. Atomic Number (Z): The number of protons in the nucleus of an atom. It uniquely identifies an element. For a neutral atom, Z also equals the number of electrons. Mass Number (A): The total number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus of an atom. $A = Z + \text{number of neutrons}$. Isotopes: Atoms of the same element (same Z) that have different numbers of neutrons (and thus different A). They have identical chemical properties but slightly different physical properties. (e.g., $^{12}C$, $^{13}C$, $^{14}C$). Isobars: Atoms of different elements (different Z) that have the same mass number (A). (e.g., $^{40}Ar$ and $^{40}Ca$). Atomic Models: Thomson's Plum Pudding Model (1904): Atom is a sphere of positive charge with electrons embedded in it. Rutherford's Nuclear Model (1911): Based on gold foil experiment. Concluded that atoms have a small, dense, positively charged nucleus, with electrons orbiting it. Failed to explain atomic stability and discrete spectra. Bohr's Model (1913): Proposed that electrons orbit the nucleus in specific, quantized energy levels or shells. Electrons can jump between levels by absorbing or emitting specific amounts of energy (photons). Explained the line spectra of hydrogen. Quantum Mechanical Model (Schrödinger, 1926): Describes electrons in terms of probabilities of finding them in certain regions of space called orbitals, rather than fixed orbits. This is the most accurate model currently. Quantum Numbers: A set of four numbers that describe the state of an electron in an atom. Principal Quantum Number (n): Describes the electron's main energy level or shell. $n = 1, 2, 3, ...$ (Higher n means higher energy and larger orbital size). Azimuthal (or Angular Momentum) Quantum Number (l): Describes the shape of the electron orbital and the subshell. $l = 0, 1, 2, ..., (n-1)$. $l=0 \implies s$ subshell (spherical shape) $l=1 \implies p$ subshell (dumbbell shape) $l=2 \implies d$ subshell (more complex shapes) $l=3 \implies f$ subshell (even more complex shapes) Magnetic Quantum Number ($m_l$): Describes the orientation of the orbital in space. $m_l = -l, (-l+1), ..., 0, ..., (l-1), l$. For $l=0$ (s orbital), $m_l=0$ (1 orbital). For $l=1$ (p orbitals), $m_l=-1, 0, +1$ (3 orbitals: $p_x, p_y, p_z$). Spin Quantum Number ($m_s$): Describes the intrinsic angular momentum (spin) of an electron. $m_s = +1/2$ or $-1/2$. Each orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons with opposite spins. Electron Configuration: The distribution of electrons of an atom or molecule in atomic or molecular orbitals. Aufbau Principle: Electrons fill orbitals starting with the lowest energy level first. Pauli Exclusion Principle: No two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers. Therefore, an atomic orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons, and these two electrons must have opposite spins. Hund's Rule of Maximum Multiplicity: For degenerate orbitals (orbitals of the same energy, e.g., the three p orbitals), electrons will fill each orbital singly with parallel spins before any orbital gets a second electron. 4. Classification of Elements and Periodicity Mendeleev's Periodic Law (1869): The properties of elements are a periodic function of their atomic masses. Arranged elements in order of increasing atomic mass, leaving gaps for undiscovered elements. Modern Periodic Law (Henry Moseley, 1913): The properties of elements are a periodic function of their atomic numbers. This resolved anomalies in Mendeleev's table. Periodic Table Structure: Periods (Horizontal Rows, 1-7): Represent the principal energy levels (n) or number of electron shells. The number of elements in a period corresponds to the maximum number of electrons that can be accommodated in the subshells being filled. Groups (Vertical Columns, 1-18): Elements in the same group have similar chemical properties because they have the same number of valence electrons (electrons in the outermost shell). Blocks of the Periodic Table: s-block (Groups 1 & 2): Alkali metals and alkaline earth metals. Valence electrons in s-orbitals. Highly reactive metals. p-block (Groups 13-18): Includes metals, metalloids, and non-metals. Valence electrons in p-orbitals. Group 18 are noble gases (full valence shell). d-block (Groups 3-12): Transition metals. Valence electrons in d-orbitals. Tend to form colored compounds and exhibit variable oxidation states. f-block (Lanthanides & Actinides): Inner transition metals. Valence electrons in f-orbitals. Often placed below the main table. Periodic Trends (General Tendencies): Atomic Radius: Decreases across a period (left to right): Increasing nuclear charge pulls electrons closer. Increases down a group (top to bottom): New electron shells are added, increasing distance from nucleus. Ionization Energy (IE): The minimum energy required to remove an electron from a gaseous atom in its ground state. Increases across a period: Stronger nuclear attraction. Decreases down a group: Electrons are further from the nucleus, less attracted. Electron Affinity (EA): The energy change that occurs when an electron is added to a gaseous atom to form a negative ion. Generally increases (becomes more negative/exothermic) across a period: Atoms gain electrons more readily. Generally decreases (becomes less negative/exothermic) down a group: Larger atoms have less attraction for an additional electron. Electronegativity: The ability of an atom in a molecule to attract shared electrons towards itself. (Pauling scale). Increases across a period: Stronger nuclear pull on bonding electrons. Decreases down a group: Valence electrons are further from the nucleus, less attraction for bonding electrons. Fluorine (F) is the most electronegative element. Metallic Character: Decreases across a period: Elements become more non-metallic. Increases down a group: Easier to lose electrons. 5. Chemical Bonding and Shapes of Molecules 5.1 Chemical Bonding - Why Atoms Bond Atoms bond to achieve a more stable electron configuration, typically a full outer shell (octet rule). This involves gaining, losing, or sharing valence electrons. Octet Rule: Atoms tend to gain, lose, or share electrons until they are surrounded by eight valence electrons. (Exceptions exist, especially for elements in period 3 and beyond, and for elements like H, He, Li, Be, B). Types of Chemical Bonds: Ionic Bond: Formed by the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions. Involves the complete transfer of one or more electrons, typically from a metal (low IE) to a non-metal (high EA). Forms crystal lattices. (e.g., NaCl, $MgCl_2$). Covalent Bond: Formed by the sharing of one or more pairs of electrons between two atoms, typically non-metals. Nonpolar Covalent Bond: Equal sharing of electrons between atoms with similar electronegativity (e.g., $H_2$, $O_2$). Polar Covalent Bond: Unequal sharing of electrons between atoms with different electronegativity, leading to partial positive ($\delta^+$) and partial negative ($\delta^-$) charges (e.g., $H_2O$, HCl). The more electronegative atom pulls the shared electrons closer. Metallic Bond: Found in metals, characterized by a "sea" of delocalized valence electrons shared among a lattice of positive metal ions. Explains properties like conductivity, malleability, and ductility. Coordinate Covalent Bond (Dative Bond): A type of covalent bond where both shared electrons come from one atom (the donor atom). (e.g., in $NH_4^+$ where N donates both electrons to H+). Lewis Structures (Lewis Dot Structures): Diagrams that show the bonding between atoms of a molecule and the lone pairs of electrons that may exist in the molecule. They help visualize valence electrons and predict bonding. Bond Polarity and Molecular Polarity: A bond is polar if there's an electronegativity difference. A molecule is polar if it contains polar bonds AND if its geometry is such that the bond dipoles do not cancel out (i.e., it has a net dipole moment). Nonpolar molecules can have polar bonds if the geometry is symmetrical (e.g., $CO_2$, $CCl_4$). 5.2 Shapes of Molecules (VSEPR Theory) VSEPR (Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion) Theory: Predicts the three-dimensional geometry of molecules based on the repulsion between electron pairs (both bonding pairs and lone pairs) in the valence shell of the central atom. Electron pairs arrange themselves as far apart as possible to minimize repulsion. Steps: Draw the Lewis structure. Count the total number of electron domains (bonding pairs + lone pairs) around the central atom. Determine the electron geometry (arrangement of electron domains). Determine the molecular geometry (arrangement of atoms, ignoring lone pairs). Common Electron Geometries and Molecular Geometries: Electron Domains Electron Geometry Bonding Pairs Lone Pairs Molecular Geometry Approx. Bond Angle Example 2 Linear 2 0 Linear 180° $CO_2$, BeCl$_2$ 3 Trigonal Planar 3 0 Trigonal Planar 120° $BF_3$, $SO_3$ 3 Trigonal Planar 2 1 Bent (V-shaped) $ $SO_2$, $O_3$ 4 Tetrahedral 4 0 Tetrahedral 109.5° $CH_4$, $CCl_4$ 4 Tetrahedral 3 1 Trigonal Pyramidal $ $NH_3$ 4 Tetrahedral 2 2 Bent (V-shaped) $ $H_2O$ 5 Trigonal Bipyramidal 5 0 Trigonal Bipyramidal 90°, 120° $PCl_5$ 5 Trigonal Bipyramidal 4 1 Seesaw $ $SF_4$ 5 Trigonal Bipyramidal 3 2 T-shaped $ $ClF_3$ 5 Trigonal Bipyramidal 2 3 Linear 180° $XeF_2$, $I_3^-$ 6 Octahedral 6 0 Octahedral 90° $SF_6$ 6 Octahedral 5 1 Square Pyramidal $ $BrF_5$ 6 Octahedral 4 2 Square Planar 90° $XeF_4$ 6. Oxidation and Reduction (Redox Reactions) Oxidation: Loss of electrons. Increase in oxidation number. Gain of oxygen atoms. Loss of hydrogen atoms. Reduction: Gain of electrons. Decrease in oxidation number. Loss of oxygen atoms. Gain of hydrogen atoms. Redox Reaction: A chemical reaction in which both oxidation and reduction occur simultaneously. Electrons are transferred from one reactant to another. Oxidizing Agent (or Oxidant): The substance that causes another substance to be oxidized. The oxidizing agent itself is reduced. Reducing Agent (or Reductant): The substance that causes another substance to be reduced. The reducing agent itself is oxidized. Oxidation Number (or Oxidation State): A number assigned to an element in a compound that represents the charge an atom would have if all bonds were ionic. Rules for assigning oxidation numbers: For a neutral element, oxidation number is 0. For a monatomic ion, oxidation number equals its charge. Oxygen usually has an oxidation number of -2 (except in peroxides, $H_2O_2$, where it's -1, and with F, where it's positive). Hydrogen usually has an oxidation number of +1 (except in metal hydrides, where it's -1). Group 1 metals are +1, Group 2 metals are +2, Fluorine is always -1. The sum of oxidation numbers in a neutral compound is 0; in a polyatomic ion, it equals the ion's charge. Balancing Redox Reactions: Can be done using the oxidation number method or the half-reaction method (ion-electron method) in acidic or basic solutions. 7. States of Matter 7.1 Gaseous State Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases (KMT): A model used to explain the behavior of ideal gases. Gases consist of a large number of identical particles (atoms or molecules) that are in continuous, random motion. The volume occupied by the gas particles themselves is negligible compared to the total volume of the container. There are no significant attractive or repulsive forces between gas particles. Collisions between gas particles and with the container walls are perfectly elastic (no net loss of kinetic energy). The average kinetic energy of the gas particles is directly proportional to the absolute temperature (in Kelvin). $KE_{avg} = \frac{3}{2}kT$. Gas Laws: Describe the relationships between pressure (P), volume (V), temperature (T), and amount (n) of a gas. Boyle's Law: At constant temperature and amount of gas, the volume of a gas is inversely proportional to its pressure. $P_1V_1 = P_2V_2$. Charles's Law: At constant pressure and amount of gas, the volume of a gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature. $\frac{V_1}{T_1} = \frac{V_2}{T_2}$. Gay-Lussac's Law: At constant volume and amount of gas, the pressure of a gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature. $\frac{P_1}{T_1} = \frac{P_2}{T_2}$. Avogadro's Law: At constant temperature and pressure, the volume of a gas is directly proportional to the number of moles of gas. $\frac{V_1}{n_1} = \frac{V_2}{n_2}$. Combined Gas Law: Combines Boyle's, Charles's, and Gay-Lussac's laws. $\frac{P_1V_1}{T_1} = \frac{P_2V_2}{T_2}$. Ideal Gas Law: Relates all four variables for an ideal gas. $PV = nRT$, where R is the ideal gas constant ($0.0821 \text{ L atm/mol K}$ or $8.314 \text{ J/mol K}$). Dalton's Law of Partial Pressures: The total pressure exerted by a mixture of non-reacting gases is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of the individual gases. $P_{total} = P_A + P_B + P_C + ...$. Partial pressure of a gas is its mole fraction multiplied by the total pressure ($P_A = \chi_A P_{total}$). Graham's Law of Effusion/Diffusion: The rate of effusion or diffusion of a gas is inversely proportional to the square root of its molar mass. $\frac{rate_1}{rate_2} = \sqrt{\frac{M_2}{M_1}}$. Real Gases: Deviate from ideal gas behavior at high pressures and low temperatures due to intermolecular forces and particle volume. Van der Waals equation can be used to describe real gases. 7.2 Liquid State Particles are close together but have enough kinetic energy to slide past one another. Indefinite shape (takes shape of container), definite volume. Properties: Viscosity: Resistance to flow (e.g., honey is more viscous than water). Increases with stronger intermolecular forces and decreases with increasing temperature. Surface Tension: The energy required to increase the surface area of a liquid by a unit amount. Caused by unbalanced intermolecular forces at the surface. Vapor Pressure: The pressure exerted by the vapor in equilibrium with its liquid phase at a given temperature. Increases with temperature and weaker intermolecular forces. Boiling Point: The temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid equals the external atmospheric pressure. Capillary Action: The movement of a liquid up a narrow tube, due to cohesive (liquid-liquid) and adhesive (liquid-surface) forces. Intermolecular Forces (IMFs): Attractive forces between molecules. Weaker than intramolecular (covalent/ionic) bonds. London Dispersion Forces (LDF): Present in all molecules, weakest, arise from temporary induced dipoles. Strength increases with molecular size/mass. Dipole-Dipole Forces: Occur between polar molecules. Stronger than LDF. Hydrogen Bonding: A special, strong type of dipole-dipole interaction occurring when H is bonded to a highly electronegative atom (N, O, F). Explains high boiling point of water. 7.3 Solid State Particles are tightly packed in fixed positions, vibrating about their equilibrium positions. Definite shape and definite volume. Types of Solids: Crystalline Solids: Possess a highly ordered, repeating three-dimensional arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules (crystal lattice). Have sharp melting points. (e.g., NaCl, diamond). Unit Cell: The smallest repeating unit of a crystal lattice. Types of Crystalline Solids: Ionic, Molecular, Covalent Network, Metallic. Amorphous Solids: Lack long-range order in their atomic arrangement. Do not have sharp melting points; soften over a range of temperatures (e.g., glass, plastic, rubber). Phase Changes: Melting (Solid to Liquid), Freezing (Liquid to Solid) Vaporization/Boiling (Liquid to Gas), Condensation (Gas to Liquid) Sublimation (Solid to Gas), Deposition (Gas to Solid) Phase Diagram: A graph showing the conditions (temperature and pressure) at which a substance exists as a solid, liquid, or gas. Triple Point: The specific temperature and pressure at which all three phases (solid, liquid, gas) coexist in equilibrium. Critical Point: The temperature and pressure above which a substance cannot exist as a liquid, regardless of pressure. Beyond this point, it is a supercritical fluid. 8. Chemical Equilibrium Reversible Reactions: Reactions that can proceed in both the forward (reactants to products) and reverse (products to reactants) directions. Represented by a double arrow ($\rightleftharpoons$). Chemical Equilibrium: A state in a reversible reaction where the rate of the forward reaction is equal to the rate of the reverse reaction. At equilibrium, the concentrations of reactants and products remain constant, but the reactions are still occurring (dynamic equilibrium). Equilibrium Constant (K): A value that expresses the ratio of product concentrations to reactant concentrations at equilibrium, each raised to the power of their stoichiometric coefficients. For a general reversible reaction: $aA + bB \rightleftharpoons cC + dD$ Concentration Equilibrium Constant ($K_c$): $$ K_c = \frac{[C]^c[D]^d}{[A]^a[B]^b} $$ (Only gaseous and aqueous species are included; solids and pure liquids have constant concentrations and are omitted). Pressure Equilibrium Constant ($K_p$): Used for gaseous reactions, where partial pressures are used instead of concentrations. $$ K_p = \frac{P_C^c P_D^d}{P_A^a P_B^b} $$ Relationship between $K_p$ and $K_c$: $K_p = K_c(RT)^{\Delta n}$, where $\Delta n = (\text{moles of gaseous products}) - (\text{moles of gaseous reactants})$. A large K value ($K \gg 1$) indicates that products are favored at equilibrium. A small K value ($K \ll 1$) indicates that reactants are favored at equilibrium. Reaction Quotient (Q): Calculated in the same way as K, but using non-equilibrium concentrations/pressures. If $Q If $Q > K$: The reaction will proceed in the reverse direction to reach equilibrium. If $Q = K$: The system is at equilibrium. Le Chatelier's Principle: If a change of condition (stress) is applied to a system in equilibrium, the system will shift in a direction that relieves the stress and re-establishes a new equilibrium. Effect of Concentration Change: Adding reactant(s): Equilibrium shifts to the right (towards products). Removing reactant(s): Equilibrium shifts to the left (towards reactants). Adding product(s): Equilibrium shifts to the left (towards reactants). Removing product(s): Equilibrium shifts to the right (towards products). Effect of Pressure Change (for gaseous reactions): Increasing pressure (by decreasing volume): Equilibrium shifts to the side with fewer moles of gas. Decreasing pressure (by increasing volume): Equilibrium shifts to the side with more moles of gas. Adding an inert gas (at constant volume): No effect on equilibrium position (partial pressures don't change). Effect of Temperature Change: Exothermic Reaction ($\Delta H Increasing temperature: Equilibrium shifts to the left (favors reactants) to absorb excess heat. Decreasing temperature: Equilibrium shifts to the right (favors products) to produce more heat. Endothermic Reaction ($\Delta H > 0$, heat is a reactant): Increasing temperature: Equilibrium shifts to the right (favors products) to absorb heat. Decreasing temperature: Equilibrium shifts to the left (favors reactants) to produce heat. Effect of Catalyst: A catalyst speeds up both the forward and reverse reaction rates equally. It helps the system reach equilibrium faster but does NOT change the position of equilibrium (K value). 9. Chemistry of Non-metals 9.1 Hydrogen (H) Atomic number 1, lightest and most abundant element in the universe. Exists as diatomic molecule, $H_2$ (dihydrogen) at standard conditions. Highly flammable, used as a fuel. Important in the synthesis of ammonia (Haber process), hydrogenation of oils. Can form ionic bonds (hydrides with active metals, e.g., NaH) or covalent bonds (with non-metals, e.g., $H_2O$, HCl). 9.2 Oxygen (O) and its Allotropes Atomic number 8, highly reactive non-metal. Dioxygen ($O_2$): The most common allotrope. Colorless, odorless gas. Essential for respiration, combustion, and many industrial processes. Paramegnetic. Ozone ($O_3$): An allotrope of oxygen. Pale blue gas with a pungent odor. Formed in the upper atmosphere by the action of UV radiation on $O_2$ ($3O_2 \xrightarrow{UV} 2O_3$). Important in the ozone layer, which absorbs harmful UV radiation from the sun. Strong oxidizing agent. Used for water purification and as a disinfectant. Depletion of the ozone layer is caused by chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other ozone-depleting substances. 9.3 Nitrogen (N) Atomic number 7, makes up about 78% of Earth's atmosphere as diatomic $N_2$ gas. $N_2$ is very inert due to the strong triple bond between the two nitrogen atoms ($N \equiv N$). Essential component of proteins, nucleic acids (DNA, RNA), and other biomolecules. Used to create inert atmospheres, in cryogenics (liquid nitrogen), and in the industrial production of ammonia (Haber process). Nitrogen fixation: Conversion of atmospheric $N_2$ into usable nitrogen compounds by bacteria or industrial processes. 9.4 Halogens (Group 17: F, Cl, Br, I, At) Highly reactive non-metals with 7 valence electrons. Eager to gain one electron to achieve a noble gas configuration, forming halide ions ($X^-$). High electronegativity (F is the most electronegative element). Exist as diatomic molecules ($F_2, Cl_2, Br_2, I_2$). Reactivity decreases down the group. Boiling points and melting points increase down the group. Fluorine ($F_2$): Pale yellow gas, most reactive element. Used in toothpaste (fluoride). Chlorine ($Cl_2$): Greenish-yellow gas, toxic. Used as a disinfectant, in PVC production, and bleaching. Bromine ($Br_2$): Reddish-brown liquid. Used in flame retardants, photography. Iodine ($I_2$): Shiny purplish-black solid, sublimes easily. Used as an antiseptic, in thyroid hormones. 9.5 Carbon (C) Atomic number 6, the basis of organic chemistry. Unique ability to form strong covalent bonds with other carbon atoms (catenation) and with many other elements, leading to a vast diversity of compounds. Can form single, double, and triple bonds. Exhibits tetravalency (forms four bonds). Allotropes of Carbon: Diamond: Tetrahedral arrangement, extremely hard, electrical insulator. Graphite: Layered hexagonal structure, soft, good electrical conductor (due to delocalized electrons). Fullerenes (e.g., Buckminsterfullerene $C_{60}$): Spherical cages of carbon atoms. Carbon Nanotubes: Cylindrical fullerenes, high strength, excellent conductors. Graphene: Single layer of graphite, strongest known material, excellent conductor. 9.6 Phosphorus (P) Atomic number 15, essential for life (ATP, DNA, RNA, bones, teeth). Exists in several allotropic forms: White Phosphorus ($P_4$): Tetrahedral structure, highly reactive, toxic, phosphorescent, ignites spontaneously in air. Stored under water. Red Phosphorus: Polymeric structure, less reactive, non-toxic, more stable than white phosphorus. Used in matchsticks. Black Phosphorus: Most stable allotrope, layered structure. Uses: Fertilizers, detergents, matches, fireworks. 9.7 Sulphur (S) Atomic number 16, typically found as a yellow solid. Exists in various allotropic forms, primarily: Rhombic Sulphur ($\alpha$-sulphur): Stable at room temperature, $S_8$ rings. Monoclinic Sulphur ($\beta$-sulphur): Stable above $95.6^\circ C$, $S_8$ rings. Uses: Production of sulfuric acid ($H_2SO_4$, a major industrial chemical), vulcanization of rubber, fungicides, gunpowder. 10. Chemistry of Metals 10.1 Metals and Metallurgical Principles Metals: Elements characterized by properties such as lustrous appearance, malleability (can be hammered into sheets), ductility (can be drawn into wires), high electrical and thermal conductivity, and typically solid at room temperature (except Hg). Tend to lose electrons to form positive ions (cations). Metallurgy: The scientific and technological process used for the extraction of metals from their ores and their refining for use. Ores: Naturally occurring rocks or minerals from which a metal can be economically extracted. Steps in Metallurgy: Concentration (Beneficiation) of Ore: Removal of gangue (impurities). Methods depend on the ore type: Gravity Separation: For ores with density difference from gangue (e.g., tin ore). Magnetic Separation: For magnetic ores (e.g., magnetite). Froth Flotation: For sulfide ores, based on preferential wetting by oil (ore) and water (gangue). Leaching: Chemical method using a solvent to dissolve the ore (e.g., cyanide leaching for gold). Extraction of Crude Metal from Concentrated Ore: Calcination: Heating carbonate ores in the absence of air to convert to oxide ($MCO_3 \xrightarrow{\Delta} MO + CO_2$). Roasting: Heating sulfide ores in the presence of air to convert to oxide ($2MS + 3O_2 \xrightarrow{\Delta} 2MO + 2SO_2$). Reduction: Conversion of metal oxide to metal using reducing agents (e.g., C, CO, Al, or electrolysis). Smelting: Reduction with carbon in a furnace (e.g., iron from iron oxide). Electrolytic Reduction: For highly reactive metals (e.g., Na, Al) where chemical reduction is difficult. Refining (Purification) of Crude Metal: Removal of remaining impurities to obtain a pure metal. Distillation: For low boiling point metals (e.g., Zn, Hg). Liquation: For metals that melt at lower temperatures than impurities (e.g., Sn, Pb). Electrolytic Refining: Most common method for highly pure metals (e.g., Cu, Ag, Au). Anode is impure metal, cathode is pure metal, electrolyte is a salt solution of the metal. Zone Refining: For ultra-pure metals (e.g., Si, Ge), based on differential solubility of impurities in molten vs. solid metal. Vapor Phase Refining: Metal is converted to a volatile compound, then decomposed to pure metal (e.g., Mond process for Ni, Van Arkel method for Ti). 10.2 Alkali Metals (Group 1: Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs, Fr) Highly reactive metals with one valence electron ($ns^1$). Readily lose this electron to form +1 ions. Soft, silvery-white, low melting points, low densities. React vigorously with water to produce hydrogen gas and metal hydroxides (alkaline solutions). $2Na(s) + 2H_2O(l) \rightarrow 2NaOH(aq) + H_2(g)$. Stored under oil to prevent reaction with air/moisture. Sodium (Na) and Potassium (K) are essential for biological functions (nerve impulses, fluid balance). 10.3 Alkaline Earth Metals (Group 2: Be, Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba, Ra) Reactive metals with two valence electrons ($ns^2$). Readily lose these electrons to form +2 ions. Harder, denser, and have higher melting points than alkali metals. React with water, but less vigorously than alkali metals. Reactivity increases down the group. Calcium (Ca) is vital for bones, teeth, muscle contraction. Magnesium (Mg) is important for chlorophyll, enzymes. 10.4 Bio-inorganic Chemistry The study of the role of inorganic elements and metal ions in biological systems. Examples: Iron (Fe): Central atom in hemoglobin (transports oxygen in blood) and myoglobin (stores oxygen in muscles). Magnesium (Mg): Central atom in chlorophyll (essential for photosynthesis in plants). Also a cofactor for many enzymes. Calcium (Ca): Major component of bones and teeth, crucial for muscle contraction, nerve transmission, and blood clotting. Zinc (Zn): Cofactor for numerous enzymes (e.g., carbonic anhydrase). Copper (Cu): Component of some oxygen-carrying proteins (hemocyanin) and enzymes. Sodium (Na) and Potassium (K): Maintain electrolyte balance, nerve impulse transmission (Na/K pump). 11. Basic Concept of Organic Chemistry 11.1 Introduction to Organic Chemistry Organic chemistry is the study of carbon-containing compounds, excluding a few simple inorganic carbon compounds like carbonates, cyanides, and carbon oxides. Unique Properties of Carbon: Tetravalency: Carbon typically forms four covalent bonds. Catenation: The ability of carbon atoms to link together to form long chains, branched chains, and rings. This property is responsible for the vast number and diversity of organic compounds. Multiple Bonding: Carbon can form single (C-C), double (C=C), and triple (C$\equiv$C) bonds with itself and with other atoms (e.g., C=O, C$\equiv$N). 11.2 Idea of Cracking and Reforming (Petroleum Refining) Cracking: The process of breaking down large, long-chain hydrocarbon molecules (found in crude oil fractions like heavy fuel oil) into smaller, more useful, and more volatile hydrocarbons (like gasoline, alkenes, and LPG). Thermal Cracking: High temperature and pressure. Catalytic Cracking: Lower temperature and pressure, uses catalysts (e.g., zeolites). Reforming (or Aromatization): The process of converting straight-chain alkanes into branched-chain alkanes or aromatic hydrocarbons. This increases the octane rating of gasoline (makes it burn more efficiently). Uses catalysts and heat. 11.3 Fundamental Principles of Organic Chemistry Functional Groups: Specific groupings of atoms within a molecule that are responsible for the characteristic chemical reactions of that molecule. They determine the chemical properties regardless of the length of the carbon chain. Functional Group General Formula Example Alkane R-H $CH_4$ (methane) Alkene C=C $C_2H_4$ (ethene) Alkyne C$\equiv$C $C_2H_2$ (ethyne) Haloalkane (Alkyl Halide) R-X (X = F, Cl, Br, I) $CH_3Cl$ (chloromethane) Alcohol R-OH $CH_3OH$ (methanol) Ether R-O-R' $CH_3OCH_3$ (dimethyl ether) Aldehyde R-CHO $CH_3CHO$ (ethanal) Ketone R-CO-R' $CH_3COCH_3$ (propanone) Carboxylic Acid R-COOH $CH_3COOH$ (ethanoic acid) Ester R-COO-R' $CH_3COOCH_3$ (methyl ethanoate) Amine R-$NH_2$, R-$NHR'$, R-$NR'R''$ $CH_3NH_2$ (methylamine) Amide R-$CONH_2$ $CH_3CONH_2$ (ethanamide) Homologous Series: A series of organic compounds with the same functional group, where each successive member differs by a $-CH_2-$ group. Members have similar chemical properties (due to same functional group). Show a gradual change in physical properties (melting point, boiling point, density) as molecular mass increases. Can be represented by a general formula (e.g., $C_nH_{2n+2}$ for alkanes). 11.4 IUPAC Nomenclature (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) A systematic method for naming organic chemical compounds to ensure each compound has a unique and unambiguous name. Basic Steps for Alkanes: Find the longest continuous carbon chain (parent chain). Number the carbons in the parent chain to give the lowest possible numbers to substituents. Identify and name substituents (e.g., methyl, ethyl, chloro). Write the name: (locant)-(substituent name)(parent chain name). Use prefixes (di-, tri-, tetra-) for multiple identical substituents. Rules for Functional Groups: The parent chain must contain the functional group. The numbering prioritizes the functional group to get the lowest possible number. Suffixes are used to indicate the functional group (e.g., -ol for alcohol, -al for aldehyde, -oic acid for carboxylic acid). 11.5 Qualitative Analysis of Organic Compounds Methods used to detect the presence of specific elements or functional groups in an organic compound. Detection of Carbon and Hydrogen: Heating with CuO; C forms $CO_2$ (turns limewater milky), H forms $H_2O$ (turns anhydrous $CuSO_4$ blue). Lassaigne's Test (Sodium Fusion Test): Used to detect nitrogen, sulfur, and halogens. The organic compound is fused with sodium metal to convert these elements into ionic forms ($NaCN, Na_2S, NaX$), which are then detected by standard tests. For Nitrogen: Formation of Prussian blue color with $FeSO_4$ and $FeCl_3$. For Sulfur: Black precipitate with sodium nitroprusside or lead acetate. For Halogens: Precipitate with $AgNO_3$ (white for Cl, pale yellow for Br, yellow for I). 11.6 Isomerism Isomers are compounds that have the same molecular formula but different arrangements of atoms. Types of Isomerism: Structural Isomerism (Constitutional Isomerism): Isomers have the same molecular formula but different connectivity of atoms (different structural formulas). Chain Isomerism: Different carbon skeletons (straight vs. branched). (e.g., n-butane and isobutane). Position Isomerism: Same carbon skeleton and functional group, but the functional group is at a different position. (e.g., 1-propanol and 2-propanol). Functional Group Isomerism: Different functional groups. (e.g., ethanol and dimethyl ether). Metamerism: Different alkyl groups attached to the same functional group (e.g., diethyl ether and methyl propyl ether). Tautomerism: A special type of functional group isomerism where isomers exist in dynamic equilibrium, often involving the migration of a proton and a double bond (e.g., keto-enol tautomerism). Stereoisomerism: Isomers have the same molecular formula and same connectivity of atoms, but different spatial arrangements of atoms. Geometrical (cis-trans) Isomerism: Occurs in molecules with restricted rotation (e.g., double bonds or rings) where groups can be on the same side (cis) or opposite sides (trans) relative to the restricted bond. Optical Isomerism (Enantiomerism): Occurs in chiral molecules (molecules that are non-superimposable on their mirror images, usually due to a chiral carbon atom with four different groups attached). Enantiomers rotate plane-polarized light in opposite directions. 11.7 Preliminary Idea of Reaction Mechanism A reaction mechanism is a step-by-step description of how a chemical reaction occurs, including the sequence of elementary steps, the breaking and formation of bonds, and the formation of intermediates and transition states. Types of Bond Fission: Homolytic Fission: Each atom involved in the bond breaking takes one of the shared electrons, forming free radicals (species with unpaired electrons). Favored by light or heat. ($A-B \rightarrow A \cdot + B \cdot$). Heterolytic Fission: One atom takes both shared electrons, forming ions (a cation and an anion). Favored by polar solvents. ($A-B \rightarrow A^+ + B^-$ or $A^- + B^+$). Types of Reagents: Electrophiles: Electron-deficient species that seek electron-rich centers (e.g., $H^+, NO_2^+, BF_3$). They are Lewis acids. Nucleophiles: Electron-rich species that seek electron-deficient centers (e.g., $OH^-, CN^-, NH_3$). They are Lewis bases. Common Reaction Types in Organic Chemistry: Substitution Reactions: An atom or group is replaced by another atom or group. (e.g., halogenation of alkanes, $S_N1/S_N2$ reactions). Addition Reactions: Atoms or groups are added across a multiple bond (double or triple bond), converting it to a single bond. Characteristic of alkenes and alkynes. Elimination Reactions: Atoms or groups are removed from a molecule, often resulting in the formation of a multiple bond. Rearrangement Reactions: Atoms or groups within a molecule rearrange to form an isomer. 12. Hydrocarbons Organic compounds composed solely of carbon and hydrogen atoms. Classified based on the type of carbon-carbon bonds present. 12.1 Saturated Hydrocarbons (Alkanes) Contain only carbon-carbon single bonds. All carbon atoms are $sp^3$ hybridized. General formula: $C_nH_{2n+2}$ (for acyclic alkanes). Also known as paraffins (from Latin "parum affinis" meaning "little affinity" due to their low reactivity). Nomenclature: Suffix "-ane" (e.g., methane, ethane, propane, butane). Physical Properties: Nonpolar, insoluble in water, soluble in nonpolar solvents. Boiling points and melting points increase with increasing molecular mass (due to stronger LDF). Chemical Reactions: Combustion: Burn in excess oxygen to produce carbon dioxide and water, releasing a large amount of energy. (e.g., $CH_4 + 2O_2 \rightarrow CO_2 + 2H_2O$). Halogenation (Free Radical Substitution): Reaction with halogens ($Cl_2, Br_2$) in the presence of UV light or high temperature. A hydrogen atom is replaced by a halogen atom. Occurs via a free radical mechanism (initiation, propagation, termination). (e.g., $CH_4 + Cl_2 \xrightarrow{UV light} CH_3Cl + HCl$). 12.2 Unsaturated Hydrocarbons (Alkenes) Contain at least one carbon-carbon double bond (C=C). Carbon atoms in the double bond are $sp^2$ hybridized. General formula: $C_nH_{2n}$ (for acyclic alkenes). Also known as olefins (oil-forming gases). Nomenclature: Suffix "-ene" (e.g., ethene, propene, but-1-ene, but-2-ene). Geometric (cis-trans) isomerism is possible. Physical Properties: Nonpolar, similar to alkanes but with slightly higher boiling points for comparable sizes. Chemical Reactions: Characterized by addition reactions across the double bond, as the $\pi$-bond is weaker and more accessible than the $\sigma$-bond. Hydrogenation: Addition of hydrogen gas ($H_2$) in the presence of a catalyst (Ni, Pt, Pd) to form an alkane. (e.g., $C_2H_4 + H_2 \xrightarrow{Ni} C_2H_6$). Halogenation: Addition of halogens ($Cl_2, Br_2$) to form dihaloalkanes. This is a test for unsaturation (bromine water test: reddish-brown color disappears). (e.g., $C_2H_4 + Br_2 \rightarrow CH_2Br-CH_2Br$). Hydrohalogenation: Addition of hydrogen halides (HCl, HBr) to form haloalkanes. Follows Markovnikov's rule (H adds to the carbon with more hydrogens already). Hydration: Addition of water ($H_2O$) in the presence of an acid catalyst to form alcohols. (e.g., $C_2H_4 + H_2O \xrightarrow{H^+} CH_3CH_2OH$). Polymerization: Alkenes can undergo addition polymerization to form long-chain polymers (e.g., ethene to polyethene). 12.3 Unsaturated Hydrocarbons (Alkynes) Contain at least one carbon-carbon triple bond (C$\equiv$C). Carbon atoms in the triple bond are $sp$ hybridized. General formula: $C_nH_{2n-2}$ (for acyclic alkynes). Nomenclature: Suffix "-yne" (e.g., ethyne (acetylene), propyne). Physical Properties: Nonpolar, similar to alkanes and alkenes. Chemical Reactions: Also characterized by addition reactions, but two molecules of reagent can add across the triple bond. Hydrogenation: Can be partially hydrogenated to alkenes (using Lindlar's catalyst) or fully hydrogenated to alkanes (using Ni, Pt, Pd). Halogenation: Addition of halogens (up to two molecules). Hydrohalogenation: Addition of hydrogen halides (up to two molecules), following Markovnikov's rule. Acidity of Terminal Alkynes: The hydrogen atom attached to a triply bonded carbon (terminal alkyne) is weakly acidic and can be removed by strong bases to form acetylide ions. This allows for reactions with metal ions (e.g., formation of silver acetylide with Tollens' reagent, a test for terminal alkynes). 13. Aromatic Hydrocarbons A class of hydrocarbons that contain one or more benzene rings or other similar cyclic, planar, conjugated systems. Aromaticity (Hückel's Rule): For a compound to be aromatic, it must be: Cyclic. Planar. Fully conjugated (has a continuous ring of p-orbitals). Possess $(4n+2)$ $\pi$ electrons (where n is a non-negative integer: 0, 1, 2, ...). Benzene has 6 $\pi$ electrons (n=1). Benzene ($C_6H_6$): The simplest aromatic hydrocarbon. A planar hexagonal ring with delocalized $\pi$ electrons, making it exceptionally stable. All C-C bond lengths are intermediate between single and double bonds. Chemical Reactions: Aromatic compounds primarily undergo electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS) reactions, where an electrophile substitutes a hydrogen atom on the ring, preserving the aromaticity. Nitration: Introduction of a nitro group ($-NO_2$) using a mixture of concentrated nitric acid and sulfuric acid. (e.g., benzene to nitrobenzene). Halogenation: Introduction of a halogen atom using a halogen ($Cl_2, Br_2$) and a Lewis acid catalyst ($FeCl_3, FeBr_3$). (e.g., benzene to chlorobenzene). Sulfonation: Introduction of a sulfonic acid group ($-SO_3H$) using fuming sulfuric acid. (e.g., benzene to benzenesulfonic acid). Friedel-Crafts Alkylation: Introduction of an alkyl group using an alkyl halide and a Lewis acid catalyst ($AlCl_3$). (e.g., benzene to toluene). Friedel-Crafts Acylation: Introduction of an acyl group (R-CO-) using an acyl halide or acid anhydride and a Lewis acid catalyst ($AlCl_3$). (e.g., benzene to acetophenone). 14. Fundamentals of Applied Chemistry 14.1 Modern Chemical Manufactures (Principles) Industrial chemical processes are designed to produce chemicals on a large scale efficiently, economically, and with minimal environmental impact. Key principles include: Raw Material Availability: Utilizing readily available and cost-effective raw materials. Energy Efficiency: Minimizing energy consumption through heat recovery, efficient catalysts, and optimized reaction conditions. Catalysis: Use of catalysts to increase reaction rates and selectivity, reducing energy costs and unwanted byproducts. Yield Optimization: Maximizing the conversion of reactants to desired products, often by adjusting temperature, pressure, concentration, and using Le Chatelier's principle. Byproduct Utilization/Waste Minimization: Finding uses for byproducts or developing processes that produce less waste (Green Chemistry principles). Safety: Ensuring safe operation for personnel and the environment. Examples of Industrial Processes: Haber Process (for Ammonia, $NH_3$): $N_2(g) + 3H_2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3(g)$ (Exothermic). Uses high pressure, moderate temperature, and an iron catalyst to shift equilibrium towards products and achieve a reasonable rate. Contact Process (for Sulfuric Acid, $H_2SO_4$): $2SO_2(g) + O_2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2SO_3(g)$ (Exothermic). Uses $V_2O_5$ catalyst. Followed by absorption of $SO_3$ in $H_2SO_4$ to form oleum, then diluted with water. 14.2 Fertilizers Substances added to soil to provide essential plant nutrients, promoting plant growth and increasing crop yields. Key Nutrients (Macronutrients): Primary Nutrients: Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P), Potassium (K). These are required in the largest quantities. Secondary Nutrients: Calcium (Ca), Magnesium (Mg), Sulfur (S). Types of Fertilizers: Nitrogenous Fertilizers: Provide nitrogen. Urea ($CO(NH_2)_2$): High nitrogen content, widely used. Ammonium Nitrate ($NH_4NO_3$): Provides both ammonium and nitrate nitrogen. Ammonium Sulfate ($(NH_4)_2SO_4$): Provides nitrogen and sulfur. Phosphatic Fertilizers: Provide phosphorus, usually as phosphate ($PO_4^{3-}$). Superphosphate: Mixture of calcium dihydrogen phosphate and calcium sulfate. Triple Superphosphate: Concentrated source of calcium dihydrogen phosphate. Potassic Fertilizers: Provide potassium, usually as potassium salts. Potassium Chloride (Muriate of Potash, KCl). Potassium Sulfate ($K_2SO_4$). Complex Fertilizers: Contain two or more primary plant nutrients (e.g., DAP - Diammonium Phosphate, NPK fertilizers). Environmental Concerns: Overuse can lead to water pollution (eutrophication from nitrate/phosphate runoff) and greenhouse gas emissions ($N_2O$ from denitrification).