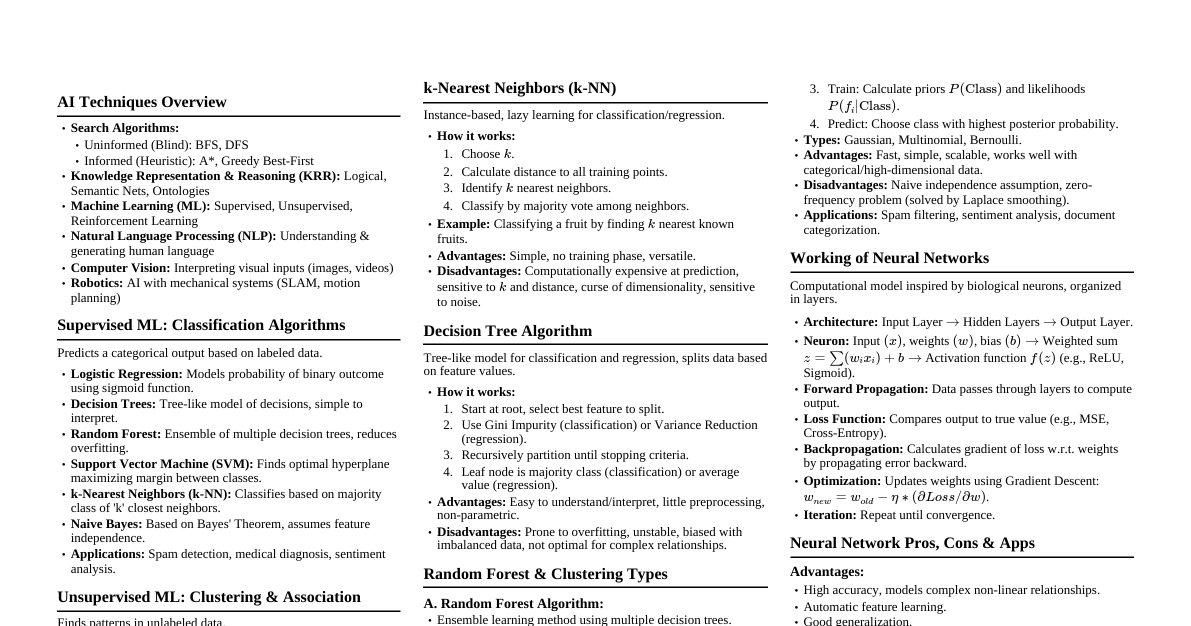

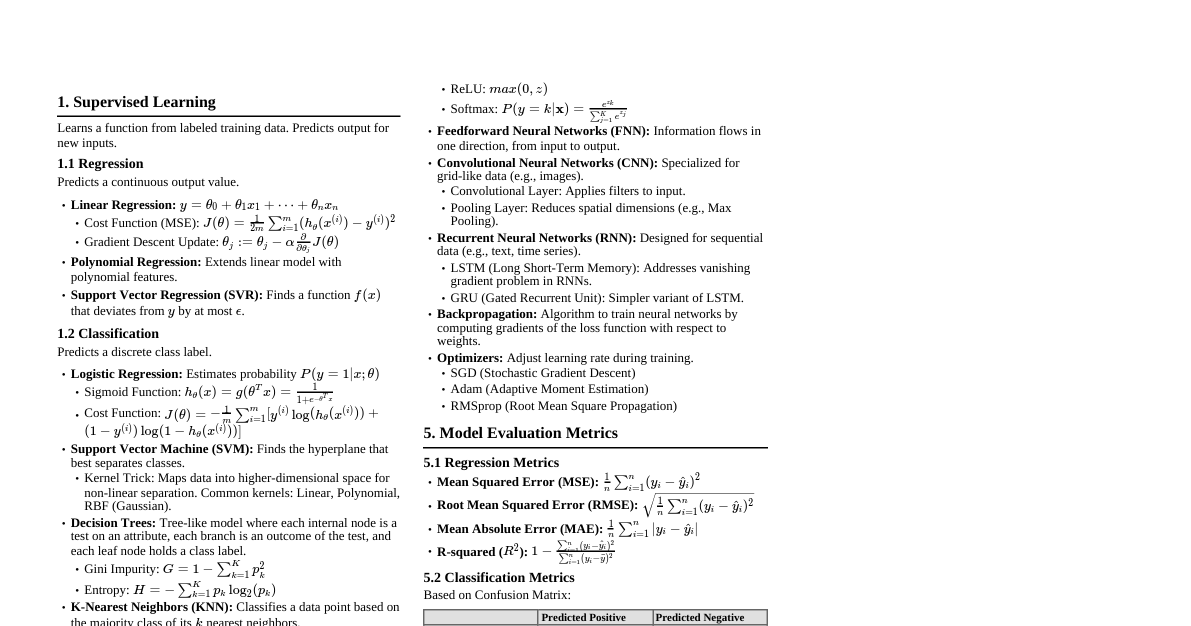

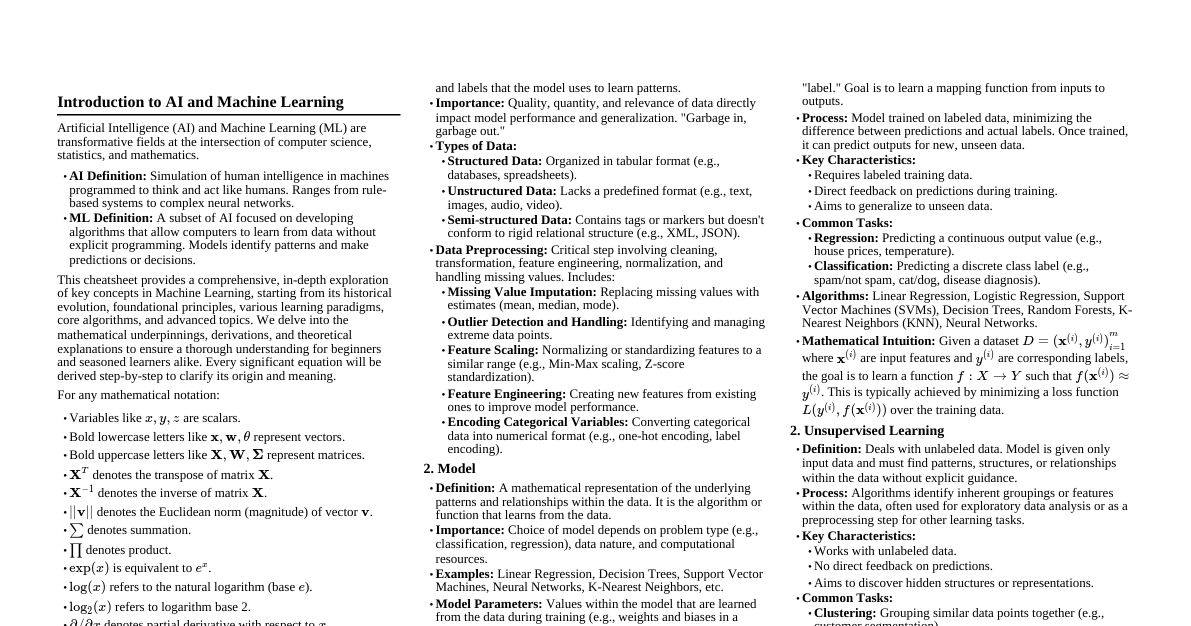

### Introduction to AI and Machine Learning Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are transformative fields at the intersection of computer science, statistics, and mathematics. This cheatsheet provides a comprehensive, in-depth exploration of key concepts in Machine Learning, starting from its historical evolution, foundational principles, various learning paradigms, core algorithms, and advanced topics. We will delve into the mathematical underpinnings, derivations, and theoretical explanations to ensure a thorough understanding for beginners and seasoned learners alike. **Key Definitions:** * **AI Definition:** Simulation of human intelligence in machines programmed to think and act like humans. It ranges from rule-based systems to complex neural networks. * **ML Definition:** A subset of AI focused on developing algorithms that allow computers to learn from data without explicit programming. Models identify patterns and make predictions or decisions. **Mathematical Notation Guide:** For clarity, mathematical notation is standardized as follows: * Scalars are represented by lowercase italic letters: $x, y, z$. * Vectors are represented by bold lowercase letters: $\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{w}, \boldsymbol{\theta}$. * Matrices are represented by bold uppercase letters: $\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{W}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}$. * Transpose of a matrix $\mathbf{X}$ is $\mathbf{X}^T$. * Inverse of a matrix $\mathbf{X}$ is $\mathbf{X}^{-1}$. * Euclidean norm (magnitude) of a vector $\mathbf{v}$ is $||\mathbf{v}||$. * Summation is denoted by $\sum$. * Product is denoted by $\prod$. * Exponential function: $\exp(x)$ is equivalent to $e^x$. * Natural logarithm (base $e$): $\log(x)$. * Logarithm base 2: $\log_2(x)$. * Partial derivative with respect to $x$: $\frac{\partial}{\partial x}$. * Gradient operator: $\nabla$. ### Evolution of AI The journey of Artificial Intelligence is long and fascinating, marked by periods of immense optimism ("AI summers") and skepticism ("AI winters"). #### Early Foundations (1940s-1950s) * **Turing Test (1950):** Alan Turing proposed a test for machine intelligence, where a human interrogator distinguishes between a human and a machine based on textual conversations. This laid the philosophical groundwork for AI. * **Perceptron (1957):** Frank Rosenblatt developed the Perceptron, the first artificial neural network, capable of learning to classify patterns. This marked the beginning of connectionism. #### The Golden Age of AI (1950s-1970s) * **Dartmouth Workshop (1956):** Considered the birth of AI as a field. John McCarthy coined the term "Artificial Intelligence." * **Logic Theorist & General Problem Solver:** Early AI programs that could prove theorems and solve general problems, demonstrating symbolic reasoning. * **Expert Systems:** Rule-based systems that encoded human expert knowledge to solve complex problems in specific domains (e.g., MYCIN for medical diagnosis). #### AI Winter (1970s-1980s) * **Limitations:** Early AI systems faced limitations in handling real-world complexity, common sense reasoning, and computational power. Funding decreased, leading to reduced research and public interest. #### Resurgence and Machine Learning Boom (1990s-2000s) * **Increased Computational Power:** Moore's Law led to more powerful and affordable computers. * **Larger Datasets:** The rise of the internet and digital data collection provided ample data for learning algorithms. * **New Algorithms:** Development of algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and ensemble methods (e.g., Random Forests) showed significant promise. * **Probabilistic Methods:** Bayesian networks and other probabilistic graphical models gained prominence. #### Deep Learning Revolution (2010s-Present) * **Deep Neural Networks:** Resurgence of neural networks with multiple layers (deep learning) achieved breakthroughs in image recognition, natural language processing, and speech recognition. * **GPUs:** Graphics Processing Units provided the parallel processing power needed to train deep models on vast datasets. * **Big Data:** Availability of massive datasets fueled the training of highly complex models. * **Reinforcement Learning:** Significant advancements in reinforcement learning (e.g., AlphaGo beating human Go champions). * **Generative AI:** Recent developments in models capable of generating realistic text, images, and other media. The evolution of AI has been a continuous cycle of innovation, challenge, and adaptation, leading to the sophisticated and ubiquitous AI systems we see today. ### Four Pillars of Machine Learning Machine Learning, at its core, relies on four fundamental components that enable systems to learn from data. Understanding these pillars is crucial for building and analyzing ML models. #### 1. Data * **Definition:** The raw material for any machine learning algorithm. Consists of observations, measurements, features, and labels that the model uses to learn patterns. * **Importance:** Quality, quantity, and relevance of data directly impact model performance and generalization. "Garbage in, garbage out." ##### Types of Data * **Structured Data:** Organized in tabular format (e.g., databases, spreadsheets). * **Unstructured Data:** Lacks a predefined format (e.g., text, images, audio, video). * **Semi-structured Data:** Contains tags or markers but doesn't conform to rigid relational structure (e.g., XML, JSON). ##### Data Preprocessing Critical steps involving cleaning, transformation, feature engineering, normalization, and handling missing values. * **Missing Value Imputation:** Replacing missing values with estimates (mean, median, mode). * **Outlier Detection and Handling:** Identifying and managing extreme data points. * **Feature Scaling:** Normalizing or standardizing features to a similar range (e.g., Min-Max scaling, Z-score standardization). * **Feature Engineering:** Creating new features from existing ones to improve model performance. * **Encoding Categorical Variables:** Converting categorical data into numerical format (e.g., one-hot encoding, label encoding). #### 2. Model * **Definition:** A mathematical representation of the underlying patterns and relationships within the data. It is the algorithm or function that learns from the data. * **Importance:** Choice of model depends on problem type (e.g., classification, regression), data nature, and computational resources. * **Examples:** Linear Regression, Decision Trees, Support Vector Machines, Neural Networks, K-Nearest Neighbors, etc. ##### Model Parameters vs. Hyperparameters * **Model Parameters:** Values within the model that are learned from the data during training (e.g., weights and biases in a neural network). Represented by symbols like $\mathbf{w}$ or $\boldsymbol{\theta}$. * **Hyperparameters:** Configuration settings external to the model, not learned from data. Set before training (e.g., learning rate, number of layers, regularization strength). #### 3. Objective Function (Loss Function / Cost Function) * **Definition:** Quantifies how well a machine learning model performs on a given dataset. Measures discrepancy between model predictions and actual target values. * **Importance:** Goal of training is to minimize this function (for loss/cost functions) or maximize it (for reward functions in reinforcement learning) to find optimal model parameters. ##### Mathematical Formulation Let $y_i$ be the true value and $\hat{y}_i$ be the predicted value for the $i$-th data point. A loss function $L(y_i, \hat{y}_i)$ calculates the error for a single data point. The overall objective function $J(\boldsymbol{\theta})$ is typically the average of these individual losses over $m$ training examples: $$J(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} L(y_i, \hat{y}_i)$$ where $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ represents the model parameters. ##### Examples * **Mean Squared Error (MSE):** For regression, $L(y_i, \hat{y}_i) = (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2$. * **Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE):** For binary classification. * **Categorical Cross-Entropy (CCE):** For multi-class classification. * **Hinge Loss:** For Support Vector Machines. #### 4. Optimization Algorithm * **Definition:** A method used to adjust the model's parameters iteratively to minimize the objective function. Finds the "best" set of parameters that make the model's predictions as accurate as possible. * **Importance:** Without an effective optimization algorithm, even a good model and abundant data cannot lead to optimal performance. * **Process:** Optimization typically involves calculating the gradient of the objective function with respect to the model parameters and then updating the parameters in the direction that reduces the loss. ##### Examples * **Gradient Descent:** Iterative optimization algorithm that takes steps proportional to the negative of the gradient of the function at the current point. * **Batch Gradient Descent:** Uses the entire dataset to compute the gradient for each step. * **Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD):** Uses a single randomly chosen data point to compute the gradient for each step. * **Mini-Batch Gradient Descent:** Uses a small random subset of the data to compute the gradient. * **Adam, RMSprop, Adagrad:** More advanced adaptive learning rate optimization algorithms. * **Newton's Method:** Uses second-order derivatives (Hessian matrix) for faster convergence but is computationally more expensive. These four pillars are interconnected and form the foundation upon which all machine learning models are built and trained. ### Machine Learning Types Machine learning paradigms are broadly categorized based on the nature of the learning signal or feedback available to the learning system. #### 1. Supervised Learning * **Definition:** Model learns from a labeled dataset, where each input data point is paired with a corresponding correct output or "label." Goal is to learn a mapping function from inputs to outputs. * **Process:** Model trained on labeled data, minimizing the difference between predictions and actual labels. Once trained, it can predict outputs for new, unseen data. * **Key Characteristics:** * Requires labeled training data. * Direct feedback on predictions during training. * Aims to generalize to unseen data. * **Common Tasks:** * **Regression:** Predicting a continuous output value (e.g., house prices, temperature). * **Classification:** Predicting a discrete class label (e.g., spam/not spam, cat/dog, disease diagnosis). * **Algorithms:** Linear Regression, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Decision Trees, Random Forests, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Neural Networks. * **Mathematical Intuition:** Given a dataset $D = \{(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, y^{(i)}) \}_{i=1}^m$, where $\mathbf{x}^{(i)}$ are input features and $y^{(i)}$ are corresponding labels, the goal is to learn a function $f: \mathbf{X} \rightarrow \mathbf{Y}$ such that $f(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) \approx y^{(i)}$. This is typically achieved by minimizing a loss function $L(y^{(i)}, f(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}))$ over the training data. #### 2. Unsupervised Learning * **Definition:** Deals with unlabeled data. Model is given only input data and must find patterns, structures, or relationships within the data without explicit guidance. * **Process:** Algorithms identify inherent groupings or features within the data, often used for exploratory data analysis or as a preprocessing step for other learning tasks. * **Key Characteristics:** * Works with unlabeled data. * No direct feedback on predictions. * Aims to discover hidden structures or representations. * **Common Tasks:** * **Clustering:** Grouping similar data points together (e.g., customer segmentation). * **Dimensionality Reduction:** Reducing the number of features while preserving important information (e.g., PCA for visualization or noise reduction). * **Association Rule Mining:** Discovering relationships between variables in large datasets (e.g., market basket analysis). * **Density Estimation:** Estimating the probability distribution of data. * **Algorithms:** K-Means Clustering, Hierarchical Clustering, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Independent Component Analysis (ICA), Autoencoders, Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs). * **Mathematical Intuition:** Given a dataset $D = \{\mathbf{x}^{(i)}\}_{i=1}^m$, the goal is to find some underlying structure or representation $\mathbf{z}^{(i)} = g(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})$ or a partition of the data $C_1, ..., C_k$ such that data points within a cluster are similar. This often involves optimizing a measure of similarity or dissimilarity. #### 3. Semi-Supervised Learning * **Definition:** Falls between supervised and unsupervised learning. Uses a combination of a small amount of labeled data and a large amount of unlabeled data for training. * **Process:** Model leverages unlabeled data to improve understanding of data distribution, enhancing performance when limited labeled data is available. Useful when labeling data is expensive. * **Key Characteristics:** * Leverages both labeled and unlabeled data. * Can achieve better performance than purely supervised learning with limited labels. * **Common Techniques:** * **Self-training:** Model trained on labeled data, then uses its own predictions on unlabeled data as "pseudo-labels" for further training. * **Co-training:** Two or more models trained on different feature sets of the same data, iteratively teaching each other. * **Generative Models:** Models like GANs or VAEs learn data distribution from unlabeled data, aiding classification tasks. * **Transductive SVMs:** Extend SVMs to handle unlabeled data by finding a decision boundary that optimally separates unlabeled points. * **Mathematical Intuition:** The objective function often combines a supervised loss term for labeled data and an unsupervised regularization term for unlabeled data, encouraging consistency across the entire dataset. #### 4. Reinforcement Learning (RL) * **Definition:** Agent learns to take actions in an "environment" to maximize a cumulative "reward." * **Process:** Agent learns through trial and error, receiving rewards for desirable actions and penalties for undesirable ones. Learns from interactions with the environment, no labeled data needed. * **Key Characteristics:** * Agent interacts with an environment. * Learns through rewards and penalties. * Goal-oriented, aims to maximize cumulative reward. * Deals with sequential decision-making. * **Components:** * **Agent:** The learner or decision-maker. * **Environment:** The world the agent interacts with. * **State:** Current situation of the environment. * **Action:** What the agent can do in a given state. * **Reward:** Numerical feedback signal indicating the desirability of an action. * **Policy:** A strategy that maps states to actions. * **Value Function:** Predicts the future reward from a given state or state-action pair. * **Common Tasks:** Robotics, game playing (e.g., AlphaGo, chess), autonomous driving, resource management, recommendation systems. * **Algorithms:** Q-learning, SARSA, Deep Q-Networks (DQN), Policy Gradients, Actor-Critic methods. * **Mathematical Intuition:** The core idea is to learn an optimal policy $\pi^*$ that maximizes the expected cumulative reward $E[\sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t R_{t+1} | S_0=s]$, where $\gamma$ is the discount factor. This often involves solving the Bellman equation. #### 5. Self-Supervised Learning * **Definition:** A form of unsupervised learning where the system generates its own labels from the input data. It creates a "pretext task" to learn useful representations without human annotation. * **Process:** A part of the input data is used to predict another part of the same data (e.g., predicting missing words, future video frames, rotated image angles). Model learns powerful feature representations, transferable to downstream supervised tasks with less labeled data. * **Key Characteristics:** * No human-annotated labels required for the pretext task. * Learns powerful general-purpose representations. * Bridges the gap between supervised and unsupervised learning. * **Common Tasks/Techniques:** * **Predicting missing parts:** Masked Language Modeling (BERT), image inpainting. * **Context prediction:** Predicting surrounding words (Word2Vec). * **Contrastive Learning:** Learning representations by pulling similar samples closer and pushing dissimilar samples apart in an embedding space (SimCLR, MoCo). * **Generative tasks:** Autoencoders, predicting future frames. * **Algorithms:** BERT, GPT, SimCLR, MAE (Masked Autoencoders). * **Mathematical Intuition:** The objective function is designed around the pretext task. For instance, in masked language modeling, it's a cross-entropy loss over the predicted masked tokens. In contrastive learning, it's a loss that maximizes agreement between different views of the same data point. #### 6. Active Learning * **Definition:** A special case of supervised learning where the algorithm interactively queries a user (or other information source) to label new data points. * **Process:** Active learner selects the most informative unlabeled data points to be labeled, reducing the amount of labeled data needed to achieve high accuracy. * **Key Characteristics:** * Learner actively queries for labels. * Aims to minimize labeling effort. * Useful when labeling is expensive. * **Query Strategies:** * **Uncertainty Sampling:** Querying data points for which the model is most uncertain about its prediction. * **Query-by-Committee:** Multiple models are trained, and the data point on which they most disagree is queried. * **Density-Weighted Uncertainty Sampling:** Considers both uncertainty and how representative a data point is of the overall data distribution. * **Mathematical Intuition:** The core is to define an informativeness measure $I(\mathbf{x})$ for unlabeled data point $\mathbf{x}$. The algorithm selects $\mathbf{x}^* = \arg \max_{\mathbf{x}} I(\mathbf{x})$ and requests its label. #### 7. Transformer Networks * **Definition:** A type of neural network architecture introduced in 2017, primarily designed for sequence-to-sequence tasks in Natural Language Processing (NLP), with applications now in computer vision and other domains. * **Key Innovation:** Attention Mechanism: Transformers revolutionized sequence modeling by replacing recurrent (RNNs) and convolutional (CNNs) layers with a self-attention mechanism. This allows the model to weigh the importance of different parts of the input sequence when processing each element, capturing long-range dependencies effectively. * **Architecture:** * **Encoder-Decoder Structure:** Both encoder and decoder composed of multiple identical layers. * **Multi-Head Self-Attention:** Allows the model to attend to different parts of the input from various "perspectives" simultaneously. * **Positional Encoding:** Added to input embeddings to provide information about the relative or absolute position of tokens, as self-attention doesn't inherently capture sequence order. * **Feed-Forward Networks:** Each attention sub-layer is followed by a simple position-wise fully connected feed-forward network. * **Layer Normalization & Residual Connections:** Used throughout the network to stabilize training and improve gradient flow. * **Advantages:** * **Parallelization:** Self-attention can be computed in parallel, leading to faster training. * **Long-Range Dependencies:** Effectively captures relationships between distant tokens in a sequence. * **State-of-the-Art Performance:** Achieved breakthrough results in machine translation, text summarization, question answering, and more. * **Algorithms/Models:** BERT, GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), T5, Vision Transformers (ViT). * **Mathematical Intuition (Self-Attention):** The core idea is to compute three vectors for each token in a sequence: Query ($\mathbf{Q}$), Key ($\mathbf{K}$), and Value ($\mathbf{V}$). The attention scores are calculated as a scaled dot product of $\mathbf{Q}$ with $\mathbf{K}^T$, passed through a softmax function, and then multiplied by $\mathbf{V}$. $$\text{Attention}(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{K}^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)\mathbf{V}$$ where $d_k$ is the dimension of the key vectors, used for scaling. #### 8. Metric Learning * **Definition:** A subfield of machine learning that aims to learn a distance function (or metric) from data. This learned metric should reflect the similarity or dissimilarity between data points in a way that is useful for downstream tasks. * **Process:** Instead of using a standard Euclidean distance, metric learning algorithms learn a transformation of the input space such that similar items are close together and dissimilar items are far apart in the transformed space. * **Importance:** A good distance metric is crucial for many algorithms that rely on similarity, such as K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), K-Means Clustering, and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) with RBF kernels. * **Key Concepts:** * **Similarity/Dissimilarity:** Defining what makes two data points "similar" or "dissimilar" based on the task. * **Embeddings:** Often involves learning an embedding space where distances directly correspond to semantic similarity. * **Common Tasks:** Face recognition, image retrieval, person re-identification, recommendation systems. * **Algorithms/Loss Functions:** * **Siamese Networks:** Neural networks that learn a mapping to an embedding space where distances between pairs of inputs are minimized for similar pairs and maximized for dissimilar pairs. * **Triplet Loss:** A loss function used in deep metric learning, where the model is trained to ensure that an "anchor" sample is closer to a "positive" sample (similar) than to a "negative" sample (dissimilar) by a certain margin. $$L(a, p, n) = \max(0, ||f(a)-f(p)||^2 - ||f(a)-f(n)||^2 + \alpha)$$ where $f(\cdot)$ is the embedding function and $\alpha$ is a margin. * **Contrastive Loss:** Similar to triplet loss, but operates on pairs of samples (positive and negative pairs). * **Mahalanobis Distance Learning:** Learning a linear transformation (matrix $\mathbf{M}$) such that the Mahalanobis distance $d_{\mathbf{M}}(\mathbf{x}_i, \mathbf{x}_j) = \sqrt{(\mathbf{x}_i - \mathbf{x}_j)^T \mathbf{M} (\mathbf{x}_i - \mathbf{x}_j)}$ reflects desired similarities. These diverse learning paradigms and architectures provide a rich toolkit for solving a wide array of problems in artificial intelligence. ### The Single Neuron (Perceptron) The single neuron, also known as the Perceptron, is the fundamental building block of artificial neural networks. Inspired by the biological neuron, it's a simple model capable of learning linear decision boundaries. #### Biological Neuron Analogy * **Dendrites:** Receive signals from other neurons (inputs). * **Cell Body (Soma):** Processes the signals. * **Axon:** Transmits the processed signal. * **Synapses:** Connections between neurons, where signals are passed and their strength can be adjusted. #### Mathematical Model of a Single Neuron A single neuron receives multiple input signals, each multiplied by a weight, sums them up, adds a bias, and then passes the result through an activation function to produce an output. 1. **Inputs ($\mathbf{x}_1, \mathbf{x}_2, ..., \mathbf{x}_n$):** Features of the input data point. 2. **Weights ($\mathbf{w}_1, \mathbf{w}_2, ..., \mathbf{w}_n$):** Each input $x_i$ is associated with a weight $w_i$. Weights represent the strength or importance of each input. 3. **Bias ($b$):** An additional parameter that allows the decision boundary to be shifted independently of the inputs. Can be thought of as an input with a constant value of 1 and its own weight. 4. **Weighted Sum (Net Input) ($z$):** Inputs are multiplied by their respective weights, and these products are summed up. The bias is then added. $$z = \sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i w_i) + b$$ In vector form, if $\mathbf{x} = [x_1, x_2, ..., x_n]^T$ and $\mathbf{w} = [w_1, w_2, ..., w_n]^T$: $$z = \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b$$ If we augment the input vector to include a constant $x_0=1$ and the weight vector to include $w_0=b$, then: $$\mathbf{x}_{\text{aug}} = [1, x_1, ..., x_n]^T$$ $$\mathbf{w}_{\text{aug}} = [b, w_1, ..., w_n]^T$$ $$z = \mathbf{w}_{\text{aug}}^T \mathbf{x}_{\text{aug}}$$ 5. **Activation Function ($f$):** The weighted sum $z$ is passed through a non-linear activation function. This function introduces non-linearity, allowing the model to learn complex patterns. 6. **Output ($\hat{y}$):** The result of the activation function is the neuron's output. $$\hat{y} = f(z) = f(\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b)$$ #### Common Activation Functions for a Single Neuron (Perceptron) For the original Perceptron, the activation function was typically a step function. For more general single neurons and in later neural networks, other functions are used. 1. **Step Function (Heaviside Step Function):** $$f(z) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } z \ge 0 \\ 0 & \text{if } z ### Regression Regression is a supervised learning task where the goal is to predict a continuous output variable (dependent variable) based on one or more input features (independent variables). #### 1. Linear Regression Linear Regression is one of the simplest and most widely used statistical models. It assumes a linear relationship between the input features and the output variable. ##### Model Hypothesis The hypothesis (or prediction) function for linear regression with $n$ features is: $$h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}) = \theta_0 + \theta_1 x_1 + \theta_2 x_2 + ... + \theta_n x_n$$ To simplify notation, we introduce a dummy feature $x_0 = 1$. Then, the feature vector becomes $\mathbf{x} = [x_0, x_1, ..., x_n]^T$ and the parameter vector is $\boldsymbol{\theta} = [\theta_0, \theta_1, ..., \theta_n]^T$. In vector form, the hypothesis is: $$h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}) = \boldsymbol{\theta}^T \mathbf{x}$$ ##### Cost Function (Mean Squared Error - MSE) To find the optimal parameters $\boldsymbol{\theta}$, we need a cost function that measures the difference between the predicted values and the actual target values. The most common choice for linear regression is the Mean Squared Error (MSE). Given a training set of $m$ examples $\{(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, y^{(i)})\}_{i=1}^m$: $$J(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \frac{1}{2m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} (h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) - y^{(i)})^2$$ The factor of $1/2$ is for mathematical convenience, as it simplifies the derivative. The goal is to minimize $J(\boldsymbol{\theta})$ with respect to $\boldsymbol{\theta}$. ##### A. Matrix-Based (Normal Equation) The normal equation provides a closed-form solution to find the optimal parameters directly, without any iterative optimization. Let $\mathbf{X}$ be the design matrix of dimensions $m \times (n+1)$, where each row is an input feature vector $\mathbf{x}^{(i)}$ (with $x_0=1$) and $\mathbf{Y}$ be the target vector of dimensions $m \times 1$. $$\mathbf{X} = \begin{bmatrix} -- (\mathbf{x}^{(1)}) -- \\ -- (\mathbf{x}^{(2)}) -- \\ \vdots \\ -- (\mathbf{x}^{(m)}) -- \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & x_1^{(1)} & \dots & x_n^{(1)} \\ 1 & x_1^{(2)} & \dots & x_n^{(2)} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 1 & x_1^{(m)} & \dots & x_n^{(m)} \end{bmatrix}$$ $$\mathbf{Y} = \begin{bmatrix} y^{(1)} \\ y^{(2)} \\ \vdots \\ y^{(m)} \end{bmatrix}$$ The vector of predictions is $\hat{\mathbf{Y}} = \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta}$. The cost function in matrix form is: $$J(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \frac{1}{2m} (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} - \mathbf{Y})^T (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} - \mathbf{Y})$$ To find the $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ that minimizes $J(\boldsymbol{\theta})$, we take the derivative with respect to $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ and set it to zero. First, recall the matrix calculus identity: $\frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{v}} (\mathbf{A}\mathbf{v} - \mathbf{b})^T (\mathbf{C}\mathbf{v} - \mathbf{d}) = \mathbf{A}^T (\mathbf{C}\mathbf{v} - \mathbf{d}) + \mathbf{C}^T (\mathbf{A}\mathbf{v} - \mathbf{b})$. In our case, let $\mathbf{v} = \boldsymbol{\theta}$, $\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{X}$, $\mathbf{b} = \mathbf{Y}$, $\mathbf{C} = \mathbf{X}$, $\mathbf{d} = \mathbf{Y}$. So, $$\frac{\partial}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}} (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} - \mathbf{Y})^T (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} - \mathbf{Y}) = \mathbf{X}^T (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} - \mathbf{Y}) + \mathbf{X}^T (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} - \mathbf{Y}) = 2 \mathbf{X}^T (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} - \mathbf{Y})$$ Now, take the derivative of $J(\boldsymbol{\theta})$: $$\nabla J(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \frac{1}{2m} (2 \mathbf{X}^T (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} - \mathbf{Y})) = \frac{1}{m} \mathbf{X}^T (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} - \mathbf{Y})$$ Set the gradient to zero to find the minimum: $$\frac{1}{m} \mathbf{X}^T (\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} - \mathbf{Y}) = \mathbf{0}$$ $$\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} - \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{Y} = \mathbf{0}$$ $$\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\theta} = \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{Y}$$ Assuming $\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}$ is invertible (which is usually the case if features are not perfectly linearly dependent and $m \ge n+1$), we can solve for $\boldsymbol{\theta}$: $$\boldsymbol{\theta} = (\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{Y}$$ * **Advantages:** No need to choose a learning rate. Guaranteed to find the global optimum in one step (because MSE is a convex function for linear regression). * **Disadvantages:** Computing $(\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X})^{-1}$ involves matrix inversion, which has a computational complexity of $O((n+1)^3)$. This becomes very slow for a large number of features $n$ (e.g., $n > 10,000$). Requires $\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}$ to be invertible (i.e., no multicollinearity or redundant features). ##### B. Gradient Descent Gradient Descent is an iterative optimization algorithm used to find the minimum of a function. For linear regression, it iteratively adjusts the parameters in the direction opposite to the gradient of the cost function. The update rule for each parameter $\theta_j$ is: $$\theta_j^{\text{new}} = \theta_j^{\text{old}} - \eta \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta_j} J(\boldsymbol{\theta})$$ where $\eta$ is the learning rate, controlling the size of the steps. Let's derive the partial derivative for $J(\boldsymbol{\theta})$: $$J(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \frac{1}{2m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} (h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) - y^{(i)})^2$$ For a single parameter $\theta_j$: $$\frac{\partial}{\partial \theta_j} J(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \frac{1}{2m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta_j} (h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) - y^{(i)})^2$$ Using the chain rule, $\frac{\partial}{\partial u} u^2 = 2u \frac{\partial u}{\partial x}$: $$ = \frac{1}{2m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} 2 (h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}) \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta_j} (h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) - y^{(i)})$$ Since $h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) = \theta_0 x_0^{(i)} + \theta_1 x_1^{(i)} + ... + \theta_j x_j^{(i)} + ... + \theta_n x_n^{(i)}$, then $\frac{\partial}{\partial \theta_j} h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) = x_j^{(i)}$. And $\frac{\partial}{\partial \theta_j} y^{(i)} = 0$ as $y^{(i)}$ is a constant with respect to $\theta_j$. So, $\frac{\partial}{\partial \theta_j} (h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}) = x_j^{(i)}$. Substituting this back: $$ = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} (h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}) x_j^{(i)}$$ Thus, the update rule for each $\theta_j$ (simultaneously for all $j$): $$\theta_j \leftarrow \theta_j - \eta \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} (h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}) x_j^{(i)}$$ This is for Batch Gradient Descent, where the gradient is calculated using the entire training set $m$ at each step. * **Variants of Gradient Descent:** * **Batch Gradient Descent:** Uses all $m$ training examples to compute the gradient. Provides stable convergence but can be very slow for large datasets. * **Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD):** Updates parameters for each training example individually. $$\theta_j \leftarrow \theta_j - \eta (h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}) x_j^{(i)}$$ for each randomly selected $i \in \{1, ..., m\}$. Much faster than batch GD for large datasets and can escape local minima in non-convex cost functions due to noisy updates, but convergence can be erratic. * **Mini-Batch Gradient Descent:** Updates parameters using a small "mini-batch" of $k$ training examples (e.g., $k=32, 64, 128$). Combines benefits of batch (stable convergence) and SGD (computational efficiency). Most commonly used approach in deep learning. $$\theta_j \leftarrow \theta_j - \eta \frac{1}{k} \sum_{i \in \text{mini-batch}} (h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}) x_j^{(i)}$$ * **Advantages of Gradient Descent:** Scales well to large numbers of features $n$. Can be used for a wide variety of models. Can handle non-invertible $\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}$. * **Disadvantages:** Requires careful selection of learning rate $\eta$. Too small, convergence is slow; too large, may overshoot minimum or diverge. Can get stuck in local minima for non-convex cost functions (though MSE for linear regression is convex, so it will find the global minimum). #### 2. Non-Linear Regression When the relationship between features and target is not linear, linear regression is insufficient. Non-linear regression models capture these complex relationships. ##### A. K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) for Regression * **Concept:** KNN is a non-parametric, instance-based learning algorithm. For a new data point, it finds the 'K' closest points in the training data (based on a distance metric, e.g., Euclidean distance) and predicts the average (or median) of their target values. * **Algorithm:** 1. Choose the number of neighbors $K$. This is a hyperparameter. 2. For a new data point $\mathbf{x}_{\text{query}}$, calculate its distance to every point $\mathbf{x}^{(i)}$ in the training set $D = \{(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, y^{(i)}) \}_{i=1}^m$. A common distance metric is Euclidean distance: $$d(\mathbf{x}_{\text{query}}, \mathbf{x}^{(i)}) = \sqrt{\sum_{j=1}^{n} (x_{\text{query},j} - x_j^{(i)})^2}$$ 3. Identify the set of $K$ training data points that have the smallest distances to $\mathbf{x}_{\text{query}}$. Let this set be $N_K(\mathbf{x}_{\text{query}})$. 4. Predict the output $\hat{y}_{\text{query}}$ as the mean of the target values of these $K$ neighbors: $$\hat{y}_{\text{query}} = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, y^{(i)}) \in N_K(\mathbf{x}_{\text{query}})} y^{(i)}$$ Alternatively, the median can be used, which is more robust to outliers. * **Advantages:** Simple to understand and implement, no explicit training phase (lazy learning), can learn complex non-linear relationships. * **Disadvantages:** Computationally expensive during prediction (needs to calculate distances to all training points), sensitive to choice of $K$ and distance metric, sensitive to irrelevant features, susceptible to the curse of dimensionality (performance degrades rapidly in high-dimensional spaces). ##### B. Support Vector Machines (SVM) for Regression (SVR) * **Concept:** While primarily known for classification, SVMs can also be extended to regression tasks, known as Support Vector Regression (SVR). Instead of trying to fit the best line through the data (like linear regression), SVR tries to fit the best line within a certain margin of tolerance (epsilon, $\epsilon$) to the target values. * **Goal:** To find a function $f(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b$ that deviates from the true targets $y$ by no more than $\epsilon$ for all training data, while simultaneously being as flat as possible (i.e., minimizing the norm of the weights, $||\mathbf{w}||^2$). This "flatness" corresponds to reduced model complexity and helps prevent overfitting. * **$\epsilon$-Insensitive Loss Function:** SVR uses an $\epsilon$-insensitive loss function, which means errors within the band of $\pm \epsilon$ from the predicted value are not penalized. $$L_{\epsilon}(y, \hat{y}) = \max(0, |y - \hat{y}| - \epsilon)$$ This loss function is zero if the absolute difference between $y$ and $\hat{y}$ is less than or equal to $\epsilon$. Otherwise, it penalizes the error linearly. * **Optimization Problem (Linear SVR):** The objective is to minimize model complexity ($||\mathbf{w}||^2$) while keeping prediction errors within $\epsilon$. We introduce slack variables $\xi_i$ and $\xi_i^*$ to allow for errors outside the $\epsilon$-tube. Minimize: $$\frac{1}{2}||\mathbf{w}||^2 + C \sum_{i=1}^{m} (\xi_i + \xi_i^*)$$ Subject to: $$y^{(i)} - (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}^{(i)} + b) \le \epsilon + \xi_i \quad \text{(for values above the tube)}$$ $$(\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}^{(i)} + b) - y^{(i)} \le \epsilon + \xi_i^* \quad \text{(for values below the tube)}$$ $$\xi_i, \xi_i^* \ge 0$$ Here, $C$ is a regularization parameter that controls the trade-off between the flatness of the function and the amount of error allowed. Larger $C$ means less tolerance for errors outside the $\epsilon$-tube. * **Non-Linear SVR with Kernels:** Similar to SVM classification, SVR can handle non-linear relationships by mapping the input data into a higher-dimensional feature space using kernel functions (e.g., Radial Basis Function - RBF kernel, polynomial kernel). In this higher-dimensional space, the relationship might be linear. The prediction function then becomes: $$f(\mathbf{x}) = \sum_{i=1}^m (\alpha_i - \alpha_i^*) K(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, \mathbf{x}) + b$$ where $\alpha_i, \alpha_i^*$ are Lagrange multipliers derived from the dual optimization problem, and $K(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, \mathbf{x})$ is the kernel function. * **Advantages:** Robust to outliers (due to $\epsilon$-insensitive loss), effective in high-dimensional spaces, can model non-linear relationships using kernels. * **Disadvantages:** Can be computationally expensive for large datasets, choice of kernel and hyperparameters ($C, \epsilon, \gamma$) is crucial. ##### C. Decision Trees for Regression * **Concept:** Decision Trees can be used for both classification and regression. For regression, the tree splits the data into subsets based on features, and at each leaf node, it predicts the average (or median) of their target values. * **Splitting Criterion:** Instead of Gini impurity or entropy (used for classification), regression trees typically use Mean Squared Error (MSE) or Mean Absolute Error (MAE) as the criterion to decide the best split. The goal is to find the split that minimizes the MSE (or MAE) of the targets within the resulting child nodes. * **Algorithm:** 1. Start with the entire training dataset at the root node. 2. For each node, iterate through all features and all possible split points for each feature. 3. For each potential split, divide the data into two child nodes (e.g., $R_1$ and $R_2$). 4. Calculate the impurity (e.g., MSE) for each child node. For a node $R$, the impurity is: $$\text{MSE}(R) = \frac{1}{|R|} \sum_{\mathbf{x}^{(i)} \in R} (y^{(i)} - \bar{y}_R)^2$$ where $\bar{y}_R$ is the average of the target values for all instances in region $R$. 5. Calculate the weighted average impurity across the child nodes: $$\text{Cost}(j, t) = \frac{|R_1|}{|R|} \text{MSE}(R_1) + \frac{|R_2|}{|R|} \text{MSE}(R_2)$$ where $j$ is the feature index and $t$ is the split threshold. 6. Select the feature and split point that minimizes this cost (i.e., maximizes the reduction in MSE). 7. Repeat steps 2-6 recursively for each child node until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., maximum depth, minimum number of samples in a leaf, minimum impurity reduction). * **Prediction:** For a new instance, traverse the tree based on its feature values until a leaf node is reached. The prediction is the average target value of the training instances in that leaf node. * **Advantages:** Easy to understand and interpret, can handle both numerical and categorical data, implicitly performs feature selection, can model complex non-linear relationships. * **Disadvantages:** Prone to overfitting (especially deep trees), can be unstable (small changes in data can lead to different tree structures), generally less accurate than ensemble methods like Random Forests or Gradient Boosting. ##### D. Polynomial Regression * **Concept:** Polynomial regression is a form of linear regression where the relationship between the independent variable $x$ and the dependent variable $y$ is modeled as an $n$-th degree polynomial. It's still considered a linear model in terms of the coefficients $\boldsymbol{\theta}$, but it can fit non-linear curves to the data. * **Hypothesis:** For a single feature $x$: $$h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(x) = \theta_0 + \theta_1 x + \theta_2 x^2 + ... + \theta_d x^d$$ where $d$ is the degree of the polynomial. * **Multiple Features:** Can be extended to multiple features, including interaction terms: $$h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}) = \theta_0 + \theta_1 x_1 + \theta_2 x_2 + \theta_3 x_1^2 + \theta_4 x_2^2 + \theta_5 x_1 x_2 + ...$$ * **Transformation:** To implement polynomial regression, you transform the original features into polynomial features. For example, if you have $x$, you create new features $x_{\text{poly},1}=x, x_{\text{poly},2}=x^2, x_{\text{poly},3}=x^3$, etc. Then, you apply standard linear regression to these transformed features. Let $\mathbf{x}_{\text{poly}} = [1, x, x^2, ..., x^d]^T$. Then $h_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}) = \boldsymbol{\theta}^T \mathbf{x}_{\text{poly}}$. * **Mathematical Intuition:** By increasing the degree $d$, the model gains more flexibility to fit complex curves. This is essentially feature engineering, where we create non-linear combinations of existing features. The optimization (finding $\boldsymbol{\theta}$) then proceeds exactly as for linear regression (Normal Equation or Gradient Descent) but on the augmented feature space. * **Advantages:** Can model non-linear relationships, relatively simple to implement (by feature transformation). * **Disadvantages:** Prone to overfitting with high polynomial degrees (leads to high variance), extrapolation beyond the data range can be unreliable, sensitive to outliers. Choosing the right degree $d$ is crucial and typically done via cross-validation. These non-linear regression techniques offer powerful ways to model complex relationships in data, moving beyond the limitations of simple linear assumptions. ### Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) A Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) is a class of feedforward artificial neural networks. It consists of at least three layers of nodes: an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Unlike a single Perceptron, MLPs can learn non-linear relationships, making them capable of solving complex problems like the XOR problem. #### Architecture of an MLP 1. **Input Layer:** * Receives the raw input features ($\mathbf{x}$). * Each node in this layer corresponds to an input feature. * No computation is performed here; they just pass the values to the next layer. 2. **Hidden Layers:** * One or more layers between the input and output layers. * Each node (neuron) in a hidden layer performs a weighted sum of its inputs from the previous layer, adds a bias, and then applies a non-linear activation function. * These layers are responsible for learning complex patterns and representations from the input data. The "deep" in deep learning refers to having many hidden layers. 3. **Output Layer:** * Receives inputs from the last hidden layer. * Each node performs a weighted sum and applies an activation function to produce the final output(s). * The number of nodes and the activation function depend on the task: * **Regression:** Usually one output node with a linear (identity) activation function. * **Binary Classification:** One output node with a sigmoid activation function (outputting probability between 0 and 1). * **Multi-class Classification:** Multiple output nodes (one per class) with a softmax activation function (outputting probabilities for each class). #### Mathematical Model of an MLP Neuron For a neuron $j$ in a hidden layer (or output layer) receiving inputs from a previous layer with $N$ neurons: 1. **Weighted Sum (Net Input) ($z_j$):** $$z_j = \sum_{i=1}^{N} W_{ji} a_i + b_j$$ where: * $a_i$ is the activation (output) of the $i$-th neuron in the previous layer. * $W_{ji}$ is the weight connecting neuron $i$ in the previous layer to neuron $j$ in the current layer. * $b_j$ is the bias term for neuron $j$. * $N$ is the number of neurons in the previous layer. In vector form, for a layer $l$: $$\mathbf{z}^{(l)} = \mathbf{W}^{(l)}\mathbf{a}^{(l-1)} + \mathbf{b}^{(l)}$$ where $\mathbf{a}^{(l-1)}$ is the vector of activations from layer $l-1$, $\mathbf{W}^{(l)}$ is the weight matrix for layer $l$, and $\mathbf{b}^{(l)}$ is the bias vector for layer $l$. 2. **Activation ($a_j$):** $$a_j = f(z_j)$$ where $f$ is the element-wise activation function. #### Activation Functions Unlike the step function of a single Perceptron, MLPs use differentiable non-linear activation functions to allow for gradient-based learning. 1. **Sigmoid (Logistic) Function:** $$f(z) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-z}}$$ * **Range:** $(0, 1)$. * **Derivative:** $f'(z) = f(z)(1 - f(z))$. * **Use:** Historically popular for hidden layers, still used in output layers for binary classification (interpretable as probability). * **Disadvantages:** **Vanishing Gradients:** For very large positive or very large negative $z$ values, the derivative $f'(z)$ becomes very close to 0. This causes gradients to shrink exponentially as they propagate backward through layers, making early layers learn very slowly. Output is not zero-centered, which can slow down gradient descent. 2. **Hyperbolic Tangent (Tanh) Function:** $$f(z) = \frac{e^z - e^{-z}}{e^z + e^{-z}}$$ * **Range:** $(-1, 1)$. * **Derivative:** $f'(z) = 1 - (f(z))^2$. * **Use:** Often preferred over sigmoid for hidden layers as its output is zero-centered, which can help gradients. * **Disadvantages:** Still suffers from vanishing gradients for large absolute values of $z$. 3. **Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) Function:** $$f(z) = \max(0, z) = \begin{cases} z & \text{if } z > 0 \\ 0 & \text{if } z \le 0 \end{cases}$$ * **Range:** $[0, \infty)$. * **Derivative:** $$f'(z) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } z > 0 \\ 0 & \text{if } z 0 \\ \alpha(e^z - 1) & \text{if } z \le 0 \end{cases}$) address the dying ReLU problem. 4. **Softmax Function:** For an output layer with $K$ nodes, given raw scores (logits) $z_1, ..., z_K$: $$P(y=k|\mathbf{x}) = \text{softmax}(z_k) = \frac{e^{z_k}}{\sum_{j=1}^{K} e^{z_j}}$$ * **Range:** $(0, 1)$ for each output, and they sum to 1 ($\sum_{k=1}^{K} P(y=k|\mathbf{x}) = 1$). * **Use:** Output layer for multi-class classification, providing a probability distribution over the classes. #### Learning in MLPs: Backpropagation MLPs are trained using the backpropagation algorithm, which is an application of the chain rule of calculus to compute the gradients of the loss function with respect to every weight and bias in the network. ##### Algorithm Steps 1. **Initialization:** Randomly initialize all weights and biases. 2. **Forward Pass:** * Input data $\mathbf{x}^{(p)}$ for a given training example $p$ is fed into the network. * Activations are computed layer by layer, from the input layer through all hidden layers to the output layer. * For each neuron $j$ in layer $l$: $$z_j^{(l)} = \sum_i W_{ji}^{(l)} a_i^{(l-1)} + b_j^{(l)}$$ $$a_j^{(l)} = f(z_j^{(l)})$$ * The final output $\hat{y}^{(p)}$ is generated. * The loss $L^{(p)}$ is calculated based on $\hat{y}^{(p)}$ and the true label $y^{(p)}$. 3. **Backward Pass (Backpropagation):** * The error is propagated backward through the network, from the output layer to the input layer. * At each layer, the error contribution of each neuron is calculated. This is typically represented by $\delta_j^{(l)} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial z_j^{(l)}}$, the error with respect to the weighted input of neuron $j$ in layer $l$. * **For the output layer (layer $L$):** $$\delta_j^{(L)} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial a_j^{(L)}} f'(z_j^{(L)})$$ The term $\frac{\partial L}{\partial a_j^{(L)}}$ depends on the choice of loss function. For example, with MSE loss $L = \frac{1}{2}(\hat{y} - y)^2$, if $a_j^{(L)} = \hat{y}_j$, then $\frac{\partial L}{\partial a_j^{(L)}} = (\hat{y}_j - y_j)$. * **For hidden layers (layer $l ### Classification Classification is a supervised learning task where the goal is to predict a discrete class label for a given input data point. The output variable is categorical. #### Types of Classification 1. **Binary Classification:** Predicts one of two possible classes (e.g., spam/not spam, disease/no disease, true/false). 2. **Multi-Class Classification:** Predicts one of more than two possible classes, where each instance belongs to exactly one class (e.g., types of animals, digits 0-9, sentiment: positive/negative/neutral). 3. **Multi-Label Classification:** Predicts multiple labels for a single instance (e.g., an image can contain both "cat" and "dog" and "grass"). #### Common Classification Algorithms Many algorithms can be adapted for classification. Here, we highlight some key ones and discuss their principles. ##### 1. Logistic Regression * **Concept:** Despite its name, Logistic Regression is a classification algorithm. It models the probability that a given input belongs to a particular class. It uses the logistic (sigmoid) function to map the linear combination of features to a probability between 0 and 1. * **Hypothesis:** For binary classification, we model the probability of the positive class ($Y=1$). Let $z = \boldsymbol{\theta}^T \mathbf{x}$ be the linear combination of features and parameters. The predicted probability $\hat{y}$ is given by the sigmoid function: $$\hat{y} = P(Y=1|\mathbf{x}; \boldsymbol{\theta}) = \sigma(z) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-z}} = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-\boldsymbol{\theta}^T \mathbf{x}}}$$ The probability of the negative class ($Y=0$) is $1 - \hat{y}$. * **Decision Boundary:** The model classifies an instance as positive if $\hat{y} \ge 0.5$ and negative if $\hat{y} 0$. ###### B. Soft Margin Classification * **Concept:** To handle non-linearly separable data and outliers, the hard margin constraint is relaxed. Soft margin SVM allows some data points to be misclassified or to lie within the margin. * **Mathematical Formulation:** We introduce non-negative slack variables $\xi_i \ge 0$ for each training example. These variables measure how much an instance violates the margin constraint. Minimize: $\frac{1}{2}||\mathbf{w}||^2 + C \sum_{i=1}^m \xi_i$ Subject to: $y^{(i)} (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}^{(i)} + b) \ge 1 - \xi_i$ for all $i = 1, ..., m$, and $\xi_i \ge 0$. Here, $C$ is a regularization parameter. The dual problem is: Maximize: $\sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i - \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^m \sum_{j=1}^m \alpha_i \alpha_j y^{(i)} y^{(j)} (\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T \mathbf{x}^{(j)}$ Subject to: $0 \le \alpha_i \le C$ for all $i = 1, ..., m$, and $\sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i y^{(i)} = 0$. ###### C. Non-Linear SVM Classification (Kernel Trick) * **Concept:** The kernel trick allows SVMs to implicitly map data into a higher-dimensional feature space where it might become linearly separable, without explicitly performing the computationally expensive mapping. * **Derivation of the Kernel Trick:** In the dual optimization problem, training data $\mathbf{x}^{(i)}$ only appears in dot products $(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T \mathbf{x}^{(j)}$. We replace this with a kernel function $K(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, \mathbf{x}^{(j)})$ that computes the dot product in a higher-dimensional feature space $\phi(\mathbf{x})$: $$K(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, \mathbf{x}^{(j)}) = \phi(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T \phi(\mathbf{x}^{(j)})$$ The dual problem becomes: Maximize: $\sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i - \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^m \sum_{j=1}^m \alpha_i \alpha_j y^{(i)} y^{(j)} K(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, \mathbf{x}^{(j)})$ Subject to: $0 \le \alpha_i \le C$ and $\sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i y^{(i)} = 0$. The decision function for a new input $\mathbf{x}_{\text{new}}$ is: $$f(\mathbf{x}_{\text{new}}) = \text{sign}\left(\sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i y^{(i)} K(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, \mathbf{x}_{\text{new}}) + b\right)$$ ###### C. Common Kernel Functions 1. **Linear Kernel:** $$K(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, \mathbf{x}^{(j)}) = (\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T \mathbf{x}^{(j)}$$ This is the simplest kernel, effectively running a linear SVM. 2. **Polynomial Kernel:** $$K(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, \mathbf{x}^{(j)}) = (\gamma (\mathbf{x}^{(i)})^T \mathbf{x}^{(j)} + r)^d$$ * $d$: degree of the polynomial. * $\gamma$: scaling parameter. * $r$: constant term. This kernel implicitly maps data to a feature space that includes polynomial combinations of the original features. 3. **Radial Basis Function (RBF) Kernel (Gaussian Kernel):** $$K(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, \mathbf{x}^{(j)}) = \exp(-\gamma ||\mathbf{x}^{(i)} - \mathbf{x}^{(j)}||^2)$$ * $\gamma$: controls the influence of a single training example. This kernel implicitly maps the data into an infinite-dimensional space and is one of the most popular kernels due to its ability to handle complex non-linear relationships. #### 3. SVM for Regression (SVR) As discussed in the Regression section, SVR uses an $\epsilon$-insensitive loss function to fit the best line within a margin of tolerance, minimizing the norm of weights. It can also use the kernel trick for non-linear regression. #### Advantages of SVMs * **Effective in high-dimensional spaces:** Especially with kernel trick, as complexity depends on number of support vectors, not dimensionality. * **Memory efficient:** Uses a subset of training points (support vectors) in the decision function. * **Versatile:** Can be used for classification, regression, and outlier detection. * **Robust to overfitting:** Due to the margin maximization principle. #### Disadvantages of SVMs * **Computational cost:** Can be slow to train on large datasets (especially with complex kernels), as the training time complexity can be between $O(m^2 n)$ and $O(m^3 n)$ depending on the implementation. * **Parameter tuning:** Requires careful selection of kernel function and hyperparameters ($C, \gamma, d, r$). * **Interpretability:** Black-box nature, especially with non-linear kernels; difficult to interpret the model's decision-making process. * **Scaling:** Requires feature scaling (normalization/standardization) for optimal performance, especially with RBF kernel. SVMs remain a powerful and theoretically elegant algorithm, particularly useful when dealing with complex datasets where the number of features is large relative to the number of samples. ### Radial Basis Function (RBF) Kernel - Detailed Derivations The Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel, also known as the Gaussian kernel, is one of the most widely used kernel functions in Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and other kernel methods. It allows SVMs to perform non-linear classification and regression by implicitly mapping the input features into an infinite-dimensional feature space. #### Concept of RBF Kernel The RBF kernel measures the similarity between two data points based on their Euclidean distance. It outputs a value between 0 and 1, where 1 indicates identical points and values close to 0 indicate very dissimilar points. #### Mathematical Definition For two data points $\mathbf{x}^{(i)}$ and $\mathbf{x}^{(j)}$, the RBF kernel function is defined as: $$K(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, \mathbf{x}^{(j)}) = \exp(-\gamma ||\mathbf{x}^{(i)} - \mathbf{x}^{(j)}||^2)$$ where: * $||\mathbf{x}^{(i)} - \mathbf{x}^{(j)}||^2$ is the squared Euclidean distance between $\mathbf{x}^{(i)}$ and $\mathbf{x}^{(j)}$. * $\gamma$ (gamma) is a positive hyperparameter that controls the "reach" or "spread" of the kernel. It is often set to $1/(2\sigma^2)$, where $\sigma$ is metaphorically the standard deviation of the Gaussian "bell curve" centered at each data point. #### Understanding the Hyperparameter $\gamma$ * **Large $\gamma$ (small $\sigma$):** * The kernel function drops off very quickly to zero as the distance between points increases. This means only data points that are extremely close to each other will have a significant kernel value. * The decision boundary becomes highly localized and complex, effectively creating small "islands" around each support vector. * High chance of overfitting the training data, as the model tries to perfectly fit every data point. * **Small $\gamma$ (large $\sigma$):** * The kernel function drops off slowly, meaning the influence of a data point extends further. * The decision boundary becomes smoother and simpler, as distant points still contribute significantly to the similarity measure. * High chance of underfitting the training data, as the model might not capture fine-grained patterns. The choice of $\gamma$ is crucial for the performance of RBF SVMs and is typically tuned using cross-validation. #### Implicit Feature Space Mapping - Derivation The power of the RBF kernel lies in its ability to implicitly map data into an infinite-dimensional feature space. Let's see how this works for a simplified 1D case. Consider $K(x_i, x_j) = \exp(-\gamma (x_i - x_j)^2)$. We can expand the exponent: $$K(x_i, x_j) = \exp(-\gamma (x_i^2 - 2x_i x_j + x_j^2)) = \exp(-\gamma x_i^2) \exp(-\gamma x_j^2) \exp(2\gamma x_i x_j)$$ Using the Taylor series expansion for $e^u = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{u^k}{k!}$: $$\exp(2\gamma x_i x_j) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{(2\gamma x_i x_j)^k}{k!} = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{(2\gamma)^k}{k!} x_i^k x_j^k$$ So, $$K(x_i, x_j) = \exp(-\gamma x_i^2) \exp(-\gamma x_j^2) \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{(2\gamma)^k}{k!} x_i^k x_j^k$$ $$K(x_i, x_j) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \left(\exp(-\gamma x_i^2) \sqrt{\frac{(2\gamma)^k}{k!}} x_i^k\right) \left(\exp(-\gamma x_j^2) \sqrt{\frac{(2\gamma)^k}{k!}} x_j^k\right)$$ This expression can be written as a dot product in an infinite-dimensional feature space. Define the feature map $\phi(x)$ as an infinite-dimensional vector where each component is: $$\phi_k(x) = \exp(-\gamma x^2) \sqrt{\frac{(2\gamma)^k}{k!}} x^k$$ Then, $K(x_i, x_j) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \phi_k(x_i) \phi_k(x_j) = \phi(x_i)^T \phi(x_j)$. This shows that the RBF kernel implicitly computes a dot product in an infinite-dimensional space. The same principle extends to higher-dimensional input vectors $\mathbf{x}$. The beauty is that we never need to explicitly compute these infinite-dimensional $\phi(\mathbf{x})$ vectors; we just use the simple RBF kernel formula. #### How it Enables Non-Linearity In the original input space, data points that are not linearly separable can often become linearly separable when mapped to a higher-dimensional space. The RBF kernel essentially allows the SVM to find a linear decision boundary in this implicitly transformed, higher-dimensional space, which corresponds to a complex non-linear decision boundary in the original input space. For example, consider concentric circles (one class inside, one outside). This is not linearly separable in 2D. However, if you map the points $(x,y)$ to a 3D space $(x, y, x^2+y^2)$, they might become linearly separable. The RBF kernel performs a much more sophisticated (infinite-dimensional) mapping. #### Use Cases * **Non-linear Classification:** Widely used in image classification, bioinformatics, text categorization, etc., where complex decision boundaries are required. * **Non-linear Regression (SVR):** Can capture non-linear relationships between features and continuous target variables. * **Density Estimation and Clustering:** Used in kernel density estimation and spectral clustering. #### Advantages of RBF Kernel * **Universal Approximator:** With appropriate parameters, RBF SVMs can model almost any continuous function, making them very powerful. * **Handles non-linear data:** Effectively transforms non-linear problems into linearly separable ones in a higher dimension. * **Relatively few hyperparameters:** Primarily $C$ (regularization) and $\gamma$ (kernel spread). #### Disadvantages of RBF Kernel * **Hyperparameter sensitivity:** Performance heavily depends on the correct tuning of $C$ and $\gamma$. * **Computational cost:** Can be slow for very large datasets, as the kernel matrix (which contains $K(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, \mathbf{x}^{(j)})$ for all pairs of training examples) grows with $m^2$. * **Interpretability:** The implicit high-dimensional mapping makes it difficult to interpret the model's decision process. * **Scaling:** Requires feature scaling (e.g., standardization) because the Euclidean distance is sensitive to feature ranges. If features have very different scales, features with larger scales might dominate the distance calculation, leading to suboptimal performance. The RBF kernel is a cornerstone of non-linear SVMs, enabling them to solve a broad range of complex real-world problems by leveraging the power of implicit high-dimensional transformations. ### Information Gain (IG) - Detailed Derivations Information Gain is a key concept in decision tree algorithms, particularly ID3 and C4.5, used to select the best attribute (feature) for splitting a node. It quantifies the expected reduction in entropy (or impurity) caused by splitting a dataset based on an attribute. The attribute with the highest information gain is chosen as the split criterion. #### 1. Entropy (A Measure of Impurity/Uncertainty) Entropy, in information theory, is a measure of the average uncertainty or "randomness" in a set of data. In the context of classification, it quantifies the impurity of a collection of examples. ##### Definition For a given set $S$ of training examples, if $P_k$ is the proportion (or probability) of examples in $S$ that belong to class $C_k$, and there are $C$ distinct classes, the entropy of $S$ is defined as: $$E(S) = - \sum_{k=1}^{C} P_k \log_2(P_k)$$ where $P_k = \frac{\text{count of examples in S belonging to class } C_k}{|S|}$. (Note: If $P_k=0$, then $0 \log_2 0$ is taken as 0, which is consistent with the limit $\lim_{x \to 0^+} x \log x = 0$). ##### Properties and Intuition * **Minimum Entropy (Pure Node):** If all examples in $S$ belong to the same class (e.g., $P_1=1, P_k=0$ for $k>1$), then $E(S) = -(1 \log_2 1) = -(1 \cdot 0) = 0$. This means there is no uncertainty; the node is perfectly pure. * **Maximum Entropy (Maximally Impure Node):** If examples are equally distributed among $C$ classes (e.g., $P_k = 1/C$ for all $k$), then $$E(S) = - \sum_{k=1}^{C} \left(\frac{1}{C}\right) \log_2\left(\frac{1}{C}\right) = - C \left(\frac{1}{C}\right) \log_2\left(\frac{1}{C}\right) = - \log_2\left(\frac{1}{C}\right) = \log_2(C)$$ For a binary classification problem ($C=2$), maximum entropy is $\log_2(2) = 1$. This occurs when $P_1=0.5, P_2=0.5$. * The higher the entropy value, the more impure or uncertain the set of examples. #### 2. Information Gain Information Gain is the reduction in entropy achieved by splitting a dataset $S$ on a particular attribute $A$. It tells us how much "information" an attribute provides about the class labels, or how much uncertainty is reduced by knowing the value of attribute $A$. ##### Definition $$\text{IG}(S, A) = E(S) - \text{Remainder}(S, A)$$ where $E(S)$ is the entropy of the parent set $S$, and $\text{Remainder}(S, A)$ is the weighted average entropy of the child nodes resulting from the split on attribute $A$. The $\text{Remainder}(S, A)$ is calculated as: $$\text{Remainder}(S, A) = \sum_{v \in \text{Values}(A)} \frac{|S_v|}{|S|} E(S_v)$$ Combining these, the full formula for Information Gain is: $$\text{IG}(S, A) = E(S) - \sum_{v \in \text{Values}(A)} \frac{|S_v|}{|S|} E(S_v)$$ where: * $S$: The current set of examples at the node to be split. * $A$: The attribute being considered for the split. * $\text{Values}(A)$: The set of all possible distinct values for attribute $A$. * $S_v$: The subset of examples in $S$ where attribute $A$ has value $v$. * $|S|$: The total number of examples in set $S$. * $|S_v|$: The number of examples in subset $S_v$. * $E(S_v)$: The entropy of the subset $S_v$. ##### Interpretation Information Gain calculates the difference between the entropy of the parent node (before split) and the weighted average entropy of the child nodes (after split). A higher Information Gain means the attribute $A$ is better at separating the data into purer subsets. The decision tree algorithm iteratively selects the attribute that yields the maximum Information Gain at each node. ##### Example Calculation Let's use the classic "Play Tennis" example. Dataset $S$ has 14 instances. Target variable (Play Tennis) has 2 classes: Yes (P) and No (N). * **Initial state of $S$:** 9 P, 5 N. * **Entropy of $S$:** $P_{\text{yes}} = 9/14, P_{\text{No}} = 5/14$. $$E(S) = - \left(\frac{9}{14}\right) \log_2\left(\frac{9}{14}\right) - \left(\frac{5}{14}\right) \log_2\left(\frac{5}{14}\right) \approx 0.831 \text{ bits}$$ (Note: Using $\log_2$ for entropy is standard, some resources might use $\ln$ for natural units or nats). Now, consider splitting on an attribute "Outlook" with values "Sunny", "Overcast", "Rain". * **Subset for Outlook = Sunny ($S_{\text{Sunny}}$):** 5 instances (2 P, 3 N). $P_{\text{yes}} = 2/5, P_{\text{No}} = 3/5$. $$E(S_{\text{Sunny}}) = - \left(\frac{2}{5}\right) \log_2\left(\frac{2}{5}\right) - \left(\frac{3}{5}\right) \log_2\left(\frac{3}{5}\right) \approx 0.971 \text{ bits}$$ * **Subset for Outlook = Overcast ($S_{\text{Overcast}}$):** 4 instances (4 P, 0 N). $P_{\text{yes}} = 4/4 = 1, P_{\text{No}} = 0/4 = 0$. $$E(S_{\text{Overcast}}) = - (1 \log_2 1) - (0 \log_2 0) = 0 \text{ bits (perfectly pure)}$$ * **Subset for Outlook = Rain ($S_{\text{Rain}}$):** 5 instances (3 P, 2 N). $P_{\text{yes}} = 3/5, P_{\text{No}} = 2/5$. $$E(S_{\text{Rain}}) = - \left(\frac{3}{5}\right) \log_2\left(\frac{3}{5}\right) - \left(\frac{2}{5}\right) \log_2\left(\frac{2}{5}\right) \approx 0.971 \text{ bits}$$ **Weighted Average Entropy (Remainder) for Outlook:** $$\text{Remainder}(S, \text{Outlook}) = \frac{5}{14} E(S_{\text{Sunny}}) + \frac{4}{14} E(S_{\text{Overcast}}) + \frac{5}{14} E(S_{\text{Rain}})$$ $$\text{Remainder}(S, \text{Outlook}) = \left(\frac{5}{14}\right)(0.971) + \left(\frac{4}{14}\right)(0) + \left(\frac{5}{14}\right)(0.971) \approx 0.347 + 0 + 0.347 \approx 0.694$$ **Information Gain for Outlook:** $$\text{IG}(S, \text{Outlook}) = E(S) - \text{Remainder}(S, \text{Outlook}) = 0.831 - 0.694 \approx 0.137$$ The decision tree algorithm would calculate IG for all available attributes (e.g., Temperature, Humidity, Wind) and choose the one with the highest IG as the best split for the current node. #### Limitations of Information Gain Information Gain has a bias towards attributes that have a large number of distinct values. An attribute with many unique values (e.g., an ID number for each instance) would likely produce many small, perfectly pure child nodes (each containing only one instance), leading to an entropy of 0 for each child node and thus a very high Information Gain. However, such a split might not generalize well to unseen data and leads to overfitting. It essentially memorizes the training data. #### Gain Ratio (Addressing the Bias) To overcome this bias, the C4.5 algorithm uses Gain Ratio. Gain Ratio normalizes Information Gain by the "Split Information" (also called Intrinsic Value) of the attribute, which measures the breadth and uniformity of the split. * **Split Information (Intrinsic Value):** Measures the entropy of the attribute's values themselves, indicating how broadly and uniformly the attribute splits the data. $$\text{SplitInfo}(S, A) = - \sum_{v \in \text{Values}(A)} \frac{|S_v|}{|S|} \log_2\left(\frac{|S_v|}{|S|}\right)$$ Attributes with many unique values will tend to have a high SplitInfo. * **Gain Ratio Formula:** $$\text{GainRatio}(S, A) = \frac{\text{IG}(S, A)}{\text{SplitInfo}(S, A)}$$ Attributes with a large number of values will have a high SplitInfo, which will reduce their Gain Ratio, thus penalizing attributes that create many small branches. This helps to select attributes that split the data into roughly equal-sized, pure subsets. Information Gain (and its variants like Gini Impurity used in CART) is fundamental to how decision trees construct their hierarchical structures, aiming to create nodes that are as pure as possible with respect to the target variable. ### Ensembling - Detailed Derivations Ensembling is a powerful technique in machine learning where multiple models (called "base learners" or "weak learners") are combined to solve the same problem. The core idea is that by combining the predictions of several models, the ensemble model can achieve better performance and robustness than any single constituent model. #### Why Ensemble? * **Reduce Variance (Bagging):** By averaging predictions, ensembles can reduce the impact of individual model errors and noise, leading to more stable and robust predictions. This is particularly effective when base models have high variance (e.g., deep decision trees). * **Reduce Bias (Boosting):** Some ensemble methods can sequentially combine weak learners that individually have high bias (e.g., shallow decision trees) to produce a strong learner that can model complex relationships, effectively reducing overall bias. * **Improve Accuracy:** Often leads to higher predictive accuracy than individual models. * **Robustness:** Less sensitive to the peculiarities of individual datasets or choices of initial parameters. #### Theoretical Justification Consider an ensemble of $M$ independent models, each with an error rate $\epsilon$. If these models are truly independent and their errors are uncorrelated, then by the law of large numbers, the error rate of a majority-voting ensemble will decrease significantly with $M$. For a binary classification task, if each base learner $h_j$ has an error rate $p 0$. d. **Update instance weights:** Update the weights of the training instances. Misclassified instances get increased weights, correctly classified instances get decreased weights. $$w_i^{(t+1)} = w_i^{(t)} \exp(-\alpha_t y^{(i)} h_t(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}))$$ Then, normalize the weights so they sum to 1: $$w_i^{(t+1)} \leftarrow \frac{w_i^{(t+1)}}{\sum_{j=1}^m w_j^{(t+1)}}$$ Note: If $y^{(i)} h_t(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})$ is positive (correct classification), the exponent is negative, so weight decreases. If it's negative (misclassification), exponent is positive, so weight increases. 3. **Final Prediction:** A weighted majority vote of all weak learners: $$H(\mathbf{x}) = \text{sign}\left(\sum_{t=1}^T \alpha_t h_t(\mathbf{x})\right)$$ * **Mathematical Intuition:** AdaBoost can be viewed as minimizing an exponential loss function. The adaptive weighting scheme effectively re-samples the training data to focus on the "hardest" examples. ##### B. Gradient Boosting (GBM) * **Concept:** A more generalized boosting algorithm that builds new base learners that predict the residuals (errors) of the previous ensemble. It frames boosting as an optimization problem where we iteratively add weak learners to minimize a differentiable loss function. * **Process (simplified for regression with MSE loss):** 1. **Initialize model:** Start with a simple model $F_0(\mathbf{x})$ (e.g., the average of the target values for regression): $$F_0(\mathbf{x}) = \arg \min_c \sum_{i=1}^m L(y^{(i)}, c)$$ For MSE, $F_0(\mathbf{x}) = \bar{y} = \frac{1}{m} \sum y^{(i)}$. 2. **For $t = 1, ..., T$ (number of weak learners):** a. **Compute pseudo-residuals:** Calculate the negative gradient of the loss function with respect to the current ensemble's predictions $F_{t-1}(\mathbf{x})$. These are called pseudo-residuals $r_i^{(t)}$. $$r_i^{(t)} = -\left[\frac{\partial L(y^{(i)}, F(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}))}{\partial F(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})}\right]_{F(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) = F_{t-1}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})}$$ For MSE loss $L(y, F) = \frac{1}{2}(y-F)^2$: $\frac{\partial L}{\partial F} = -(y-F) = F-y$. So, $r_i^{(t)} = y^{(i)} - F_{t-1}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})$, which are the actual residuals. b. **Train weak learner:** Train a new weak learner $h_t(\mathbf{x})$ (e.g., a decision tree) to predict these pseudo-residuals $r_i^{(t)}$. c. **Find optimal step size:** Determine the optimal step size (or learning rate) $\gamma_t$ for the new learner by minimizing the loss function when adding $h_t(\mathbf{x})$ to the ensemble: $$\gamma_t = \arg \min_{\gamma} \sum_{i=1}^m L(y^{(i)}, F_{t-1}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) + \gamma h_t(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}))$$ d. **Update model:** Add the new learner, scaled by $\gamma_t$ and a global learning rate $\eta$, to the ensemble: $$F_t(\mathbf{x}) = F_{t-1}(\mathbf{x}) + \eta \gamma_t h_t(\mathbf{x})$$ 3. **Final Prediction:** The final model is $F_T(\mathbf{x})$. * **Key Idea:** Gradient Boosting iteratively fits new models to the residuals (or more generally, the negative gradients) of the previous models. This means each new model tries to correct the errors made by the aggregate of all previous models, pushing the overall prediction towards the true values. * **Advantages:** Highly accurate, flexible (can use various loss functions and base learners), state-of-the-art performance on many tabular datasets. * **Disadvantages:** Prone to overfitting if not tuned (especially learning rate $\eta$ and number of trees $T$), computationally intensive, sensitive to noisy data. * **Advanced Variants:** XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost are highly optimized and regularized implementations of gradient boosting that offer significant performance improvements through techniques like second-order gradients, regularization, and parallelization. #### 4. Stacking (Stacked Generalization) * **Concept:** A more complex ensemble method where multiple base models (level-0 models) are trained on the data, and then a meta-model (level-1 model) is trained on the predictions of the base models. * **Process:** 1. **Level-0 Models:** Train several diverse base learners (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, Logistic Regression) on the training data. 2. **Meta-Feature Generation (Cross-Validation):** To prevent data leakage (where the meta-model sees predictions on data it was trained on), a common approach is to use k-fold cross-validation. a. Divide the training data into $k$ folds. b. For each fold, train the level-0 models on the other $k-1$ folds. c. Use these trained models to make predictions on the held-out fold. These predictions become the meta-features for that fold. d. Aggregate these predictions to create a new dataset where each instance has the predictions from all level-0 models as its features, along with the original target variable. 3. **Level-1 Model (Meta-learner):** Train a separate model (e.g., Logistic Regression, Ridge Regression, or a simple neural network) on these meta-features (the predictions from level-0 models) to make the final prediction. * **Key Idea:** Allows the meta-model to learn how to best combine the predictions of the base models, often by learning their strengths and weaknesses and potentially correcting for their biases. * **Advantages:** Can achieve very high accuracy by leveraging the strengths of different models, often outperforms bagging and boosting in complex scenarios. * **Disadvantages:** Complex to implement, computationally expensive (requires training multiple models and cross-validation), risk of overfitting the meta-model if not careful. Ensemble methods are fundamental to achieving high performance in many real-world machine learning applications and are a crucial part of any data scientist's toolkit. ### Principal Component Analysis (PCA) - Detailed Derivations Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a widely used unsupervised learning technique for dimensionality reduction. Its primary goal is to transform a high-dimensional dataset into a lower-dimensional one while retaining as much of the original variance (information) as possible. #### 1. Motivation for Dimensionality Reduction * **Curse of Dimensionality:** In high-dimensional spaces, data becomes sparse, making it difficult for learning algorithms to find patterns. * **Noise Reduction:** High-dimensional data often contains redundant or noisy features, which can hinder model performance. * **Visualization:** Difficult to visualize data with more than 3 dimensions. PCA can reduce dimensions to 2 or 3 for plotting. * **Computational Efficiency:** Reducing the number of features can significantly speed up training time for subsequent machine learning algorithms. * **Storage Space:** Less memory required to store the data. #### 2. Core Idea of PCA PCA identifies directions (principal components) in the data where the variance is maximized. These principal components are orthogonal to each other, meaning they are uncorrelated. The first principal component captures the most variance, the second captures the next most variance orthogonal to the first, and so on. #### 3. Mathematical Steps of PCA Given a dataset $\mathbf{X}$ with $m$ samples and $n$ features. $$\mathbf{X} = \begin{bmatrix} X_{11} & X_{12} & \dots & X_{1n} \\ X_{21} & X_{22} & \dots & X_{2n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ X_{m1} & X_{m2} & \dots & X_{mn} \end{bmatrix}$$ ##### Step 1: Standardize the Data It's crucial to standardize the data before applying PCA, especially if features have different scales or units. Features with larger scales might dominate the principal components. For each feature $j \in \{1, ..., n\}$: $$x_{ij}^{\text{scaled}} = \frac{X_{ij} - \mu_j}{\sigma_j}$$ where $\mu_j = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m X_{ij}$ is the mean of feature $j$ and $\sigma_j = \sqrt{\frac{1}{m-1} \sum_{i=1}^m (X_{ij} - \mu_j)^2}$ is the standard deviation of feature $j$. After standardization, each feature will have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Let the standardized data matrix be $\mathbf{X}_c$. ##### Step 2: Compute the Covariance Matrix The covariance matrix $\boldsymbol{\Sigma}$ (often denoted $\mathbf{C}$) of the scaled data describes the relationships between all pairs of features. For a dataset $\mathbf{X}$ where each column is a feature and is already mean-centered (which is true after standardization), the covariance matrix is given by: $$\boldsymbol{\Sigma} = \frac{1}{m-1} \mathbf{X}_c^T \mathbf{X}_c$$ * The diagonal elements $\Sigma_{jj}$ represent the variance of feature $j$. * The off-diagonal elements $\Sigma_{jk}$ represent the covariance between feature $j$ and feature $k$. * **Positive covariance:** features tend to increase/decrease together. * **Negative covariance:** one feature tends to increase while the other decreases. * **Zero covariance:** features are linearly uncorrelated. * The covariance matrix is always symmetric. ##### Step 3: Compute Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues of the Covariance Matrix Eigenvectors and eigenvalues are central to PCA. They define the principal components. For a square matrix $\boldsymbol{\Sigma}$ (our covariance matrix), an eigenvector $\mathbf{v}$ and its corresponding eigenvalue $\lambda$ satisfy the equation: $$\boldsymbol{\Sigma} \mathbf{v} = \lambda \mathbf{v}$$ This can be rewritten as $(\boldsymbol{\Sigma} - \lambda \mathbf{I}) \mathbf{v} = \mathbf{0}$, where $\mathbf{I}$ is the identity matrix. For non-trivial solutions ($\mathbf{v} \ne \mathbf{0}$), the determinant of $(\boldsymbol{\Sigma} - \lambda \mathbf{I})$ must be zero: $$\det(\boldsymbol{\Sigma} - \lambda \mathbf{I}) = 0$$ This is the characteristic equation, a polynomial whose roots are the eigenvalues $\lambda$. Once the eigenvalues are found, they are plugged back into $(\boldsymbol{\Sigma} - \lambda \mathbf{I}) \mathbf{v} = \mathbf{0}$ to find the corresponding eigenvectors. * **Eigenvectors:** Represent the directions (principal components) along which the data varies the most. They form an orthogonal basis for the feature space. * **Eigenvalues:** Represent the magnitude of variance along their corresponding eigenvector. A larger eigenvalue means more variance is captured along that principal component. ##### Step 4: Sort Eigenvectors by Decreasing Eigenvalues Order the calculated eigenvectors from highest to lowest corresponding eigenvalue. * The eigenvector with the highest eigenvalue is the first principal component (PC1), capturing the most variance. * The eigenvector with the second highest eigenvalue is the second principal component (PC2), capturing the next most variance, and is orthogonal to PC1. * And so on, until the $n$-th principal component. ##### Step 5: Select a Subset of Principal Components Choose the top $k$ eigenvectors (principal components) that correspond to the largest eigenvalues. These $k$ eigenvectors will form a new feature subspace. The number $k$ is the desired dimensionality of the reduced data ($k \le n$). The choice of $k$ can be based on: * **Explained Variance Ratio:** Calculate the proportion of variance explained by each principal component: $\lambda_j / \sum_{i=1}^n \lambda_i$. Then, sum these ratios for the top $k$ components to achieve a desired cumulative explained variance (e.g., 95% or 99%). This is often visualized with a cumulative explained variance plot. * **Scree Plot:** Plot eigenvalues in decreasing order and look for an "elbow" point where the eigenvalues drop off sharply. This "elbow" suggests a natural cutoff for the number of components. * **Application-specific requirements:** For visualization, $k=2$ or $k=3$ is chosen. ##### Step 6: Project Data onto the New Feature Subspace Form a projection matrix $\mathbf{W}$ by taking the top $k$ selected eigenvectors and arranging them as columns. Each column $\mathbf{v}_j$ is a principal component. $$\mathbf{W} = [\mathbf{v}_1, \mathbf{v}_2, ..., \mathbf{v}_k]$$ The new, reduced-dimensional dataset $\mathbf{Z}$ is obtained by multiplying the original (scaled and centered) data matrix $\mathbf{X}_c$ by the projection matrix $\mathbf{W}$: $$\mathbf{Z} = \mathbf{X}_c \mathbf{W}$$ The new matrix $\mathbf{Z}$ will have dimensions $m \times k$, where each column represents a principal component score for the data points. These principal component scores are the new features, representing the data in the lower-dimensional space. #### Example: 2D to 1D PCA Imagine 2D data points forming an elongated cloud. 1. **Center the data:** Subtract the mean from each dimension. 2. **Compute covariance matrix:** This matrix will tell us how $x_1$ and $x_2$ vary together. $$\boldsymbol{\Sigma} = \begin{bmatrix} \text{Var}(x_1) & \text{Cov}(x_1, x_2) \\ \text{Cov}(x_2, x_1) & \text{Var}(x_2) \end{bmatrix}$$ 3. **Find eigenvectors and eigenvalues:** * The first eigenvector will be aligned with the longest axis of the data cloud (the direction of maximum variance). * The second eigenvector will be orthogonal to the first (in 2D for two features). * The eigenvalue for the first eigenvector will be much larger than the second, indicating that much more variance is captured along the first principal component. 4. **Select a subset:** Choose only the first eigenvector (PC1) to reduce to 1D. 5. **Project data:** Project all 2D data points onto the line defined by the first eigenvector. The data is now 1D, having lost the least amount of information possible by retaining the direction of maximum variance. #### Advantages of PCA * **Dimensionality Reduction:** Reduces the number of features, combating the curse of dimensionality and making subsequent computations faster. * **Noise Reduction:** By focusing on directions of highest variance, PCA often filters out noise present in less significant dimensions (components with low eigenvalues are often associated with noise). * **Decorrelation:** Transforms correlated features into a set of uncorrelated features (principal components). This can be beneficial for algorithms that assume feature independence. * **Visualization:** Enables visualization of high-dimensional data in 2 or 3 dimensions, which is otherwise impossible. #### Disadvantages of PCA * **Loss of Information:** Reduces dimensionality by discarding some variance, which means some information is lost (though ideally, the least important information). * **Interpretability:** Principal components are linear combinations of original features. This makes them less interpretable than the original features. For example, "PC1" might be "0.7 featureA + 0.3 featureB - 0.2 featureC", which is harder to understand than "featureA". * **Assumes Linearity:** PCA is a linear transformation. It may not perform well if the data has complex non-linear structures (for which non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques like t-SNE or UMAP might be better). * **Sensitive to Feature Scaling:** As noted in Step 1, PCA is sensitive to the scaling of features. Improper scaling can lead to components being dominated by features with higher magnitudes. * **Not Feature Selection:** PCA combines features rather than selecting a subset of original features. If you need to know which original features are most important, other methods are needed. PCA is a fundamental tool in data analysis and machine learning, particularly useful for preprocessing high-dimensional data before applying other algorithms, and for exploratory data analysis.