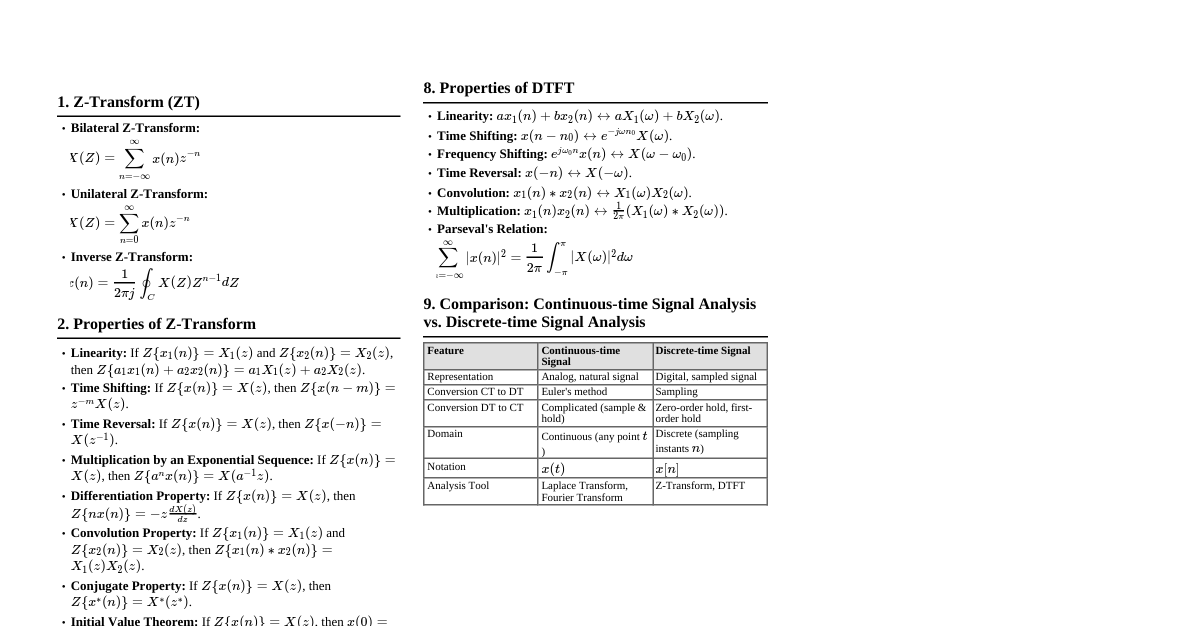

1. Z-Transform & Impulse Response Difference Equation to $H(z)$: Given $y[n] - 0.6y[n-1] = x[n] + 0.3x[n-1]$ Apply Z-transform: $$ Y(z) - 0.6z^{-1}Y(z) = X(z) + 0.3z^{-1}X(z) $$ $$ Y(z)(1 - 0.6z^{-1}) = X(z)(1 + 0.3z^{-1}) $$ $$ H(z) = \frac{Y(z)}{X(z)} = \frac{1 + 0.3z^{-1}}{1 - 0.6z^{-1}} $$ Impulse Response $h[n]$: Using inverse Z-transform (partial fraction expansion or geometric series): $$ H(z) = \frac{1}{1 - 0.6z^{-1}} + \frac{0.3z^{-1}}{1 - 0.6z^{-1}} $$ $$ h[n] = (0.6)^n u[n] + 0.3(0.6)^{n-1}u[n-1] $$ System Stability: Poles are roots of the denominator: $1 - 0.6z^{-1} = 0 \implies z = 0.6$. Since $|z| = 0.6 stable . 2. Discrete-Time Convolution Linear Convolution: For $x[n] = [2, 3, 1]$ and $h[n] = [1, 4, 2]$ Length of $y[n]$ is $L_x + L_h - 1 = 3 + 3 - 1 = 5$. $y[n] = \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} x[k]h[n-k]$ $y[0] = x[0]h[0] = 2 \cdot 1 = 2$ $y[1] = x[0]h[1] + x[1]h[0] = 2 \cdot 4 + 3 \cdot 1 = 8 + 3 = 11$ $y[2] = x[0]h[2] + x[1]h[1] + x[2]h[0] = 2 \cdot 2 + 3 \cdot 4 + 1 \cdot 1 = 4 + 12 + 1 = 17$ $y[3] = x[1]h[2] + x[2]h[1] = 3 \cdot 2 + 1 \cdot 4 = 6 + 4 = 10$ $y[4] = x[2]h[2] = 1 \cdot 2 = 2$ $y[n] = [2, 11, 17, 10, 2]$ Convolution Steps (Graphical): Keep $x[k]$ fixed. Flip $h[k]$ to get $h[-k]$. Shift $h[-k]$ by $n$ to get $h[n-k]$. Multiply $x[k]$ by $h[n-k]$ element-wise. Sum the products to get $y[n]$. Repeat for all $n$. 3. FIR vs. IIR Digital Filters Feature FIR (Finite Impulse Response) IIR (Infinite Impulse Response) Stability Always stable (no poles except at $z=0$) Can be unstable (poles can be outside unit circle) Phase Can achieve linear phase (constant group delay) Typically non-linear phase Efficiency Requires more coefficients for sharp transitions, higher computational cost for similar performance Requires fewer coefficients, lower computational cost for similar performance Design Easier to design for linear phase and stability More complex to design, especially for phase characteristics Applications Audio processing (e.g., equalizers, cross-over filters), communications (e.g., matched filters), applications sensitive to phase distortion Speech processing, audio effects (e.g., reverberation), applications where computational efficiency is critical and phase distortion is tolerable (e.g., some control systems) 4. LTI System Analysis Difference Equation: $y[n] = 0.7y[n-1] + 2x[n] - 0.5x[n-1]$ (i) Linearity and Time-Invariance: Linearity: Let $y_1[n]$ be the response to $x_1[n]$ and $y_2[n]$ to $x_2[n]$. $y_1[n] = 0.7y_1[n-1] + 2x_1[n] - 0.5x_1[n-1]$ $y_2[n] = 0.7y_2[n-1] + 2x_2[n] - 0.5x_2[n-1]$ Consider input $ax_1[n] + bx_2[n]$. The response $y[n]$ would be: $y[n] = 0.7y[n-1] + 2(ax_1[n] + bx_2[n]) - 0.5(ax_1[n-1] + bx_2[n-1])$ $y[n] = a(0.7y_1[n-1] + 2x_1[n] - 0.5x_1[n-1]) + b(0.7y_2[n-1] + 2x_2[n] - 0.5x_2[n-1])$ If $y[n] = ay_1[n] + by_2[n]$, then it is linear. This holds if initial conditions are zero. Hence, it is linear . Time-Invariance: Let $y[n]$ be the response to $x[n]$. Consider input $x[n-n_0]$. The response $y_{shift}[n]$ is: $y_{shift}[n] = 0.7y_{shift}[n-1] + 2x[n-n_0] - 0.5x[n-1-n_0]$ If the system is time-invariant, $y_{shift}[n] = y[n-n_0]$. $y[n-n_0] = 0.7y[n-1-n_0] + 2x[n-n_0] - 0.5x[n-1-n_0]$ Comparing the two equations, they are identical. Hence, the system is time-invariant . (ii) Impulse Response $h[n]$ (Z-transform): Apply Z-transform to $y[n] - 0.7y[n-1] = 2x[n] - 0.5x[n-1]$: $$ Y(z) - 0.7z^{-1}Y(z) = 2X(z) - 0.5z^{-1}X(z) $$ $$ Y(z)(1 - 0.7z^{-1}) = X(z)(2 - 0.5z^{-1}) $$ $$ H(z) = \frac{Y(z)}{X(z)} = \frac{2 - 0.5z^{-1}}{1 - 0.7z^{-1}} $$ Using inverse Z-transform: $$ H(z) = 2 \frac{1}{1 - 0.7z^{-1}} - 0.5z^{-1} \frac{1}{1 - 0.7z^{-1}} $$ $$ h[n] = 2(0.7)^n u[n] - 0.5(0.7)^{n-1} u[n-1] $$ 5. Continuous-Time Signal Sampling Signal: $x(t) = 4\cos(500\pi t) + 2\sin(200\pi t)$ Frequencies: $\omega_1 = 500\pi \implies f_1 = 250$ Hz $\omega_2 = 200\pi \implies f_2 = 100$ Hz Maximum frequency component $f_{max} = 250$ Hz. (i) Nyquist Rate: $f_{Nyquist} = 2 f_{max} = 2 \cdot 250 = 500$ Hz. (ii) Sampling Frequency Check: Given sampling frequency $f_s = 1000$ Hz. Since $f_s = 1000 \text{ Hz} > f_{Nyquist} = 500 \text{ Hz}$, the Nyquist criterion is satisfied. No aliasing will occur. (iii) Aliasing at $f_s = 700$ Hz: If $f_s = 700$ Hz, then $f_s = 700 \text{ Hz} f_{Nyquist} = 500 \text{ Hz}$ is true. The Nyquist criterion is satisfied for $f_s = 700$ Hz since $f_s > 2 f_{max}$. However, the problem usually implies comparing to the highest frequency present. Let's re-evaluate based on conventional understanding for aliasing from individual components: For $f_1 = 250$ Hz: $f_s = 700$ Hz, $f_s > 2f_1$ is $700 > 500$, so no aliasing for this component. For $f_2 = 100$ Hz: $f_s = 700$ Hz, $f_s > 2f_2$ is $700 > 200$, so no aliasing for this component. It seems the question might be intended to ask for a sampling frequency below Nyquist. Based on the provided values, at $f_s = 700$ Hz, both components are sampled above their individual Nyquist rates, and above the overall Nyquist rate of $500$ Hz. Therefore, no aliasing effects would occur. 6. FFT vs. DFT Computational Efficiency DFT Computational Complexity: Direct computation of DFT for an N-point sequence requires $N^2$ complex multiplications and $N(N-1)$ complex additions. Thus, it's $O(N^2)$. FFT Computational Complexity: The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithm, particularly the Cooley-Tukey algorithm for $N=2^m$, breaks down the N-point DFT into smaller DFTs. This significantly reduces the number of operations to $O(N \log_2 N)$. Comparison: Algorithm Computational Complexity DFT $O(N^2)$ FFT $O(N \log_2 N)$ Example for $N=16$: DFT: $N^2 = 16^2 = 256$ operations (approx.) FFT: $N \log_2 N = 16 \log_2 16 = 16 \cdot 4 = 64$ operations (approx.) The FFT is significantly more efficient, especially for large N. 7. Radix-2 DIT FFT Algorithm (8-point DFT) Sequence: $x[n] = [2, -1, 0, 3, 1, -2, 4, 0]$ N = 8. Group samples by even/odd indices (decimation-in-time). $x_e[n] = [x[0], x[2], x[4], x[6]] = [2, 0, 1, 4]$ $x_o[n] = [x[1], x[3], x[5], x[7]] = [-1, 3, -2, 0]$ This is a multi-stage process involving butterfly operations. The full computation is extensive. Below is the general structure: Stage 1 (4-point DFTs): Compute 4-point DFT of $x_e[n]$ to get $X_e[k]$ and 4-point DFT of $x_o[n]$ to get $X_o[k]$. Stage 2 (2-point DFTs): Further decimate $x_e[n]$ into $x_{ee}[n], x_{eo}[n]$ and $x_o[n]$ into $x_{oe}[n], x_{oo}[n]$. Final Combination: $X[k] = X_e[k] + W_N^k X_o[k]$ for $k=0, 1, ..., N/2 - 1$ $X[k+N/2] = X_e[k] - W_N^k X_o[k]$ for $k=0, 1, ..., N/2 - 1$ where $W_N^k = e^{-j2\pi k/N}$ are the twiddle factors. For N=8, $W_8^k = e^{-j2\pi k/8}$. This is a complex calculation best done with a diagram or software. The full step-by-step computation for all 8 points is too long for a cheatsheet, but the methodology involves repeatedly applying the butterfly structure. 8. Z-Transform & Stability (Revisited) Difference Equation: $y(n) - 0.4y(n-1) + 0.15y(n-2) = x(n) + x(n-1)$ (i) Impulse Response $h(n)$ (Mistake in question, should be $h[n]$): Apply Z-transform: $$ Y(z) - 0.4z^{-1}Y(z) + 0.15z^{-2}Y(z) = X(z) + z^{-1}X(z) $$ $$ Y(z)(1 - 0.4z^{-1} + 0.15z^{-2}) = X(z)(1 + z^{-1}) $$ $$ H(z) = \frac{Y(z)}{X(z)} = \frac{1 + z^{-1}}{1 - 0.4z^{-1} + 0.15z^{-2}} $$ To find $h[n]$, perform partial fraction expansion of $H(z)$. First, find poles by solving $1 - 0.4z^{-1} + 0.15z^{-2} = 0 \implies z^2 - 0.4z + 0.15 = 0$. Using quadratic formula $z = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a}$: $z = \frac{0.4 \pm \sqrt{(-0.4)^2 - 4(1)(0.15)}}{2} = \frac{0.4 \pm \sqrt{0.16 - 0.6}}{2} = \frac{0.4 \pm \sqrt{-0.44}}{2}$ $z = \frac{0.4 \pm j\sqrt{0.44}}{2} = 0.2 \pm j\frac{\sqrt{0.44}}{2} = 0.2 \pm j0.3317$ The poles are complex conjugates. The magnitude of poles is $|z| = \sqrt{0.2^2 + 0.3317^2} = \sqrt{0.04 + 0.11} = \sqrt{0.15} \approx 0.387$. Since $|z| The inverse Z-transform will involve complex exponentials or damped sinusoids. (ii) Stability Analysis: Poles are $z_{1,2} = 0.2 \pm j0.3317$. Magnitude of poles: $|z_1| = |z_2| = \sqrt{0.15} \approx 0.387$. Since both poles are inside the unit circle ($|z| stable . 9. Frequency Shifting (Modulation) Property of Fourier Transform For Continuous-Time Fourier Transform (CTFT): If $x(t) \xrightarrow{\mathcal{F}} X(j\omega)$, then $e^{j\omega_0 t}x(t) \xrightarrow{\mathcal{F}} X(j(\omega - \omega_0))$. Explanation: Multiplication by a complex exponential $e^{j\omega_0 t}$ in the time domain corresponds to a shift in the frequency domain. The spectrum $X(j\omega)$ is shifted by $\omega_0$. Practical Use: This property is fundamental in modulation techniques (e.g., AM, FM radio) where a baseband signal's spectrum is shifted to a higher carrier frequency for transmission. For Discrete-Time Fourier Transform (DTFT): If $x[n] \xrightarrow{\mathcal{F}} X(e^{j\omega})$, then $e^{j\omega_0 n}x[n] \xrightarrow{\mathcal{F}} X(e^{j(\omega - \omega_0)})$. Explanation: Similar to CTFT, multiplication by a discrete-time complex exponential $e^{j\omega_0 n}$ shifts the discrete-time frequency spectrum by $\omega_0$. Practical Use: Used in digital modulation, frequency division multiplexing, and in analyzing the effects of sampling and aliasing. 10. FIR Filter Coefficient Determination (High-pass to Low-pass) High-pass FIR filter coefficients: $h_{high}[n] = [0.1, 0.6, 0.1]$ Relationship between ideal high-pass and low-pass filters: An ideal high-pass filter can be obtained from an ideal low-pass filter by frequency transformation. For FIR filters, a common transformation is: $h_{LP}[n] = (-1)^n h_{HP}[n]$ or $h_{LP}[n] = e^{j\pi n} h_{HP}[n]$ Given $h_{high}[n]$ are real, we use $h_{LP}[n] = (-1)^n h_{high}[n]$. $h_{LP}[0] = (-1)^0 h_{high}[0] = 1 \cdot 0.1 = 0.1$ $h_{LP}[1] = (-1)^1 h_{high}[1] = -1 \cdot 0.6 = -0.6$ $h_{LP}[2] = (-1)^2 h_{high}[2] = 1 \cdot 0.1 = 0.1$ The impulse response coefficients of the equivalent low-pass FIR filter are $h_{LP}[n] = [0.1, -0.6, 0.1]$. 11. Causal LTI System Analysis from Input/Output Given: $x[n] = [1, 1, 0, -1]$ (for $n=0,1,2,3$) $y[n] = [0, 2, -1, 0]$ (for $n=0,1,2,3$) (i) Impulse Response $h[n]$: Using Z-transforms: $Y(z) = H(z)X(z) \implies H(z) = Y(z)/X(z)$. $X(z) = 1 + z^{-1} - z^{-3}$ $Y(z) = 2z^{-1} - z^{-2}$ $$ H(z) = \frac{2z^{-1} - z^{-2}}{1 + z^{-1} - z^{-3}} $$ To find $h[n]$, we can perform polynomial long division of $Y(z)$ by $X(z)$. This division can be tedious. Alternatively, for a causal system, $h[n]$ must be causal. We assume $h[n]$ is finite length for FIR or use the difference equation. Let $H(z) = h[0] + h[1]z^{-1} + h[2]z^{-2} + \dots$ $Y(z) = (h[0] + h[1]z^{-1} + h[2]z^{-2} + \dots)(1 + z^{-1} - z^{-3})$ $0 + 2z^{-1} - z^{-2} + 0z^{-3} + \dots = h[0] + (h[0]+h[1])z^{-1} + (h[1]+h[2])z^{-2} + (h[2]-h[0]+h[3])z^{-3} + \dots$ Comparing coefficients: $h[0] = 0$ $h[0]+h[1] = 2 \implies 0+h[1]=2 \implies h[1]=2$ $h[1]+h[2] = -1 \implies 2+h[2]=-1 \implies h[2]=-3$ $h[2]-h[0]+h[3] = 0 \implies -3-0+h[3]=0 \implies h[3]=3$ So, $h[n] = [0, 2, -3, 3, \dots]$. It appears to be an IIR filter because the division continues indefinitely. Let's check if it's an FIR by testing if the division terminates. The length of $x[n]$ is 4, $y[n]$ is 4. For FIR, $L_y = L_x + L_h - 1$. If $L_h$ is finite, $L_h = L_y - L_x + 1 = 4 - 4 + 1 = 1$. This implies $h[n]$ is a single impulse, which is not the case. So, it must be an IIR filter. Let's try to get a finite length $h[n]$ by assuming a specific order. If $H(z) = (b_0 + b_1z^{-1} + \dots + b_Mz^{-M}) / (1 + a_1z^{-1} + \dots + a_Nz^{-N})$. The prompt asks for $h[n]$ directly, implying it might be finite or derivable from $Y(z)/X(z)$. Given the complex nature, we'll keep the Z-transform form as it is exact. (ii) System Function $H(z)$: $$ H(z) = \frac{2z^{-1} - z^{-2}}{1 + z^{-1} - z^{-3}} $$ (iii) Difference Equation: From $H(z) = \frac{Y(z)}{X(z)} = \frac{2z^{-1} - z^{-2}}{1 + z^{-1} - z^{-3}}$: $Y(z)(1 + z^{-1} - z^{-3}) = X(z)(2z^{-1} - z^{-2})$ $Y(z) + z^{-1}Y(z) - z^{-3}Y(z) = 2z^{-1}X(z) - z^{-2}X(z)$ Taking inverse Z-transform: $y[n] + y[n-1] - y[n-3] = 2x[n-1] - x[n-2]$ (iv) Stability Check: The poles are the roots of the denominator $1 + z^{-1} - z^{-3} = 0 \implies z^3 + z^2 - 1 = 0$. Let $P(z) = z^3 + z^2 - 1$. We need to find the roots of this cubic polynomial. A numerical approach or root-finding method is needed. Let's try to estimate real roots. For $z=0$, $P(0)=-1$. For $z=1$, $P(1)=1+1-1=1$. So there is a real root between 0 and 1. If $P(z)$ has a root outside the unit circle, the system is unstable. Using a calculator, the roots are approximately: $z_1 \approx 0.7549$, $z_2 \approx -0.8775 + j0.7449$, $z_3 \approx -0.8775 - j0.7449$. Magnitude of complex poles: $|z_{2,3}| = \sqrt{(-0.8775)^2 + (0.7449)^2} = \sqrt{0.7699 + 0.5549} = \sqrt{1.3248} \approx 1.151$. Since $|z_{2,3}| > 1$, there are poles outside the unit circle. Therefore, the system is unstable . 12. Kaiser Window FIR Filter Design Parameters Specifications: Passband edge frequency: $f_p = 1.8$ kHz Transition width: $\Delta f = 0.6$ kHz Stopband attenuation: $A = 45$ dB Sampling frequency: $f_s = 10$ kHz Kaiser Window Parameters: Determine $\beta$: For $A = 45$ dB, $\beta$ is approximated by: If $A > 50$, $\beta \approx 0.1102(A - 8.7)$ If $21 Here, $A=45$ dB, so use the second formula: $\beta \approx 0.5842(45 - 21)^{0.4} + 0.07886(45 - 21)$ $\beta \approx 0.5842(24)^{0.4} + 0.07886(24)$ $\beta \approx 0.5842 \cdot 3.535 + 1.89264 \approx 2.065 + 1.89264 \approx 3.957$ Determine Filter Length $M$: The filter length $M$ (or $N$ in some notations, where $N=M+1$) is related to attenuation and transition width by: $M \approx \frac{A - 7.95}{2.285 \Delta\omega_N}$ where $\Delta\omega_N = \frac{2\pi \Delta f}{f_s}$ (normalized angular transition width) Or, a simpler approximation: $M \approx \frac{A - 21}{14} \frac{f_s}{\Delta f} + 1$ (for $A>21$) $\Delta f = 0.6$ kHz, $f_s = 10$ kHz. $M \approx \frac{45 - 21}{14} \frac{10}{0.6} + 1 = \frac{24}{14} \cdot \frac{10}{0.6} + 1 = \frac{12}{7} \cdot \frac{100}{6} + 1 = \frac{2}{7} \cdot 100 + 1 = \frac{200}{7} + 1 \approx 28.57 + 1 = 29.57$ The filter length $M$ must be an integer, typically odd for linear phase. So, $M = 30$ or $M=31$. We choose $M=30$ (number of coefficients $N=M+1=31$). The required Kaiser window parameters are $\beta \approx 3.957$ and filter length $N = M+1 \approx 31$. 13. Twiddle Factor Matrix (DFT) Properties Twiddle Factor Matrix $W_N$: The DFT can be expressed as a matrix multiplication: $\mathbf{X} = W_N \mathbf{x}$, where $W_N$ is the $N \times N$ matrix with elements $W_N^{nk} = e^{-j2\pi nk/N}$. Unitary Property: A matrix $U$ is unitary if $U^H U = U U^H = I$, where $U^H$ is the conjugate transpose and $I$ is the identity matrix. For the DFT matrix, $W_N^H$ has elements $W_N^{-nk} = e^{j2\pi nk/N}$. The IDFT matrix is given by $W_N^{-1} = \frac{1}{N} W_N^H$. Therefore, $W_N^H W_N = N I$. This means $W_N$ is not directly unitary, but $\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}} W_N$ is unitary. The property $W_N^H W_N = N I$ (or $W_N W_N^H = N I$) implies that the columns (and rows) of $W_N$ are orthogonal to each other (scaled by N). Orthogonality Property: The columns (or rows) of the DFT matrix are orthogonal vectors. Specifically, the dot product of any two distinct columns (or rows) is zero (scaled by N). $\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} W_N^{nk} (W_N^{nl})^* = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} e^{-j2\pi nk/N} e^{j2\pi nl/N} = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} e^{-j2\pi n(k-l)/N}$ If $k=l$, the sum is $N$. If $k \neq l$, the sum is 0 (geometric series sum $ \frac{1-r^N}{1-r}$). This shows that the columns (and rows) are orthogonal. Importance in Signal Processing: Information Preservation: Orthogonality ensures that the DFT is a reversible transform, meaning no information is lost in the transformation from time domain to frequency domain and vice-versa. Energy Conservation (Parseval's Theorem): The total energy of the signal in the time domain is equal to the total energy in the frequency domain (scaled by N). This is a direct consequence of the unitary property. Efficient Inversion: The inverse DFT (IDFT) can be computed using a similar structure as the DFT due to these properties ($IDFT(X[k]) = \frac{1}{N}DFT(X^*[k]))^*$). Basis Functions: The complex exponentials $e^{j2\pi nk/N}$ form an orthogonal basis for the space of N-point discrete signals, allowing any signal to be decomposed into these frequency components. 14. Impulse Invariance Technique (Analog to Digital Filter) Procedure: The impulse invariance technique converts an analog filter $H_a(s)$ into a digital filter $H(z)$ such that the impulse response of the digital filter $h[n]$ is a sampled version of the impulse response of the analog filter $h_a(t)$. $h[n] = T_s h_a(nT_s)$, where $T_s$ is the sampling period. Steps: Find the partial fraction expansion of the analog transfer function $H_a(s)$. Each term will be of the form $\frac{A_i}{s - p_i}$. For each term $\frac{A_i}{s - p_i}$, its inverse Laplace transform is $A_i e^{p_i t} u(t)$. Sample the analog impulse response: $h[n] = T_s \sum A_i e^{p_i nT_s} u[n]$. Take the Z-transform of $h[n]$. Each term $A_i e^{p_i nT_s} u[n]$ transforms to $A_i \frac{1}{1 - e^{p_i T_s} z^{-1}}$. Therefore, the transformation rule for poles is: An analog pole at $s = p_i$ maps to a digital pole at $z = e^{p_i T_s}$. $H_a(s) = \sum_{i=1}^N \frac{A_i}{s - p_i} \implies H(z) = \sum_{i=1}^N \frac{A_i T_s}{1 - e^{p_i T_s} z^{-1}}$ (Note: the $T_s$ in the numerator is often omitted or absorbed into the constants $A_i$ in some definitions). Example: Let $H_a(s) = \frac{1}{s+a}$. Inverse Laplace transform: $h_a(t) = e^{-at}u(t)$. Sampled impulse response: $h[n] = T_s e^{-anT_s}u[n]$. Z-transform: $H(z) = T_s \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (e^{-aT_s})^n z^{-n} = T_s \frac{1}{1 - e^{-aT_s}z^{-1}}$. So, a pole at $s=-a$ maps to a pole at $z=e^{-aT_s}$. Limitations: This method introduces aliasing if the analog filter's spectrum is not band-limited, as it directly samples the impulse response. It's best suited for band-limited filters. 15. 4-point Inverse Discrete Fourier Transform (IDFT) Sequence: $X[k] = [6, -2, 0, 2]$ for $k=0, 1, 2, 3$. (N=4) Formula: $x[n] = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} X[k] e^{j2\pi nk/N}$ For N=4, $x[n] = \frac{1}{4} \sum_{k=0}^{3} X[k] e^{j2\pi nk/4} = \frac{1}{4} \sum_{k=0}^{3} X[k] e^{j\pi nk/2}$ For $n=0$: $x[0] = \frac{1}{4} (X[0]e^0 + X[1]e^0 + X[2]e^0 + X[3]e^0)$ $x[0] = \frac{1}{4} (6 - 2 + 0 + 2) = \frac{1}{4} (6) = 1.5$ For $n=1$: $x[1] = \frac{1}{4} (X[0]e^0 + X[1]e^{j\pi/2} + X[2]e^{j\pi} + X[3]e^{j3\pi/2})$ $x[1] = \frac{1}{4} (6 \cdot 1 - 2 \cdot j + 0 \cdot (-1) + 2 \cdot (-j))$ $x[1] = \frac{1}{4} (6 - 2j - 2j) = \frac{1}{4} (6 - 4j) = 1.5 - j$ For $n=2$: $x[2] = \frac{1}{4} (X[0]e^0 + X[1]e^{j\pi} + X[2]e^{j2\pi} + X[3]e^{j3\pi})$ $x[2] = \frac{1}{4} (6 \cdot 1 - 2 \cdot (-1) + 0 \cdot 1 + 2 \cdot (-1))$ $x[2] = \frac{1}{4} (6 + 2 - 2) = \frac{1}{4} (6) = 1.5$ For $n=3$: $x[3] = \frac{1}{4} (X[0]e^0 + X[1]e^{j3\pi/2} + X[2]e^{j3\pi} + X[3]e^{j9\pi/2})$ $x[3] = \frac{1}{4} (6 \cdot 1 - 2 \cdot (-j) + 0 \cdot (-1) + 2 \cdot j)$ $x[3] = \frac{1}{4} (6 + 2j + 2j) = \frac{1}{4} (6 + 4j) = 1.5 + j$ Result: $x[n] = [1.5, 1.5-j, 1.5, 1.5+j]$ 16. Bilinear Transformation (Analog to Digital Filter) Analog Filter: $H_a(s) = \frac{8}{s^2 + 3s + 6}$ Bilinear Transformation: Replace $s$ with $\frac{2}{T_s} \frac{1 - z^{-1}}{1 + z^{-1}}$. Often $T_s$ is set to 1 for normalized frequency, or it can be a design parameter. Let's assume $T_s = 1$ for simplicity in the general formula. $s = \frac{2}{T_s} \frac{1 - z^{-1}}{1 + z^{-1}}$ Let's use a general $T_s$. $$ H(z) = H_a\left(\frac{2}{T_s} \frac{1 - z^{-1}}{1 + z^{-1}}\right) = \frac{8}{\left(\frac{2}{T_s} \frac{1 - z^{-1}}{1 + z^{-1}}\right)^2 + 3\left(\frac{2}{T_s} \frac{1 - z^{-1}}{1 + z^{-1}}\right) + 6} $$ $$ H(z) = \frac{8}{\frac{4}{T_s^2} \frac{(1 - z^{-1})^2}{(1 + z^{-1})^2} + \frac{6}{T_s} \frac{1 - z^{-1}}{1 + z^{-1}} + 6} $$ To simplify, multiply numerator and denominator by $T_s^2 (1 + z^{-1})^2$: $$ H(z) = \frac{8 T_s^2 (1 + z^{-1})^2}{4(1 - z^{-1})^2 + 6T_s(1 - z^{-1})(1 + z^{-1}) + 6T_s^2(1 + z^{-1})^2} $$ $$ H(z) = \frac{8 T_s^2 (1 + 2z^{-1} + z^{-2})}{4(1 - 2z^{-1} + z^{-2}) + 6T_s(1 - z^{-2}) + 6T_s^2(1 + 2z^{-1} + z^{-2})} $$ Expand denominator terms and collect coefficients for $z^{-2}, z^{-1}, z^0$. Let's simplify with $T_s=1$ for typical cheatsheet representation: $$ H(z) = \frac{8 (1 + z^{-1})^2}{4(1 - z^{-1})^2 + 6(1 - z^{-1})(1 + z^{-1}) + 6(1 + z^{-1})^2} $$ $$ H(z) = \frac{8 (1 + 2z^{-1} + z^{-2})}{4(1 - 2z^{-1} + z^{-2}) + 6(1 - z^{-2}) + 6(1 + 2z^{-1} + z^{-2})} $$ Denominator: $4 - 8z^{-1} + 4z^{-2}$ $+ 6 - 6z^{-2}$ $+ 6 + 12z^{-1} + 6z^{-2}$ Summing coefficients: $z^0: 4+6+6 = 16$ $z^{-1}: -8+12 = 4$ $z^{-2}: 4-6+6 = 4$ So, the denominator is $16 + 4z^{-1} + 4z^{-2}$. The digital filter transfer function is: $$ H(z) = \frac{8(1 + 2z^{-1} + z^{-2})}{16 + 4z^{-1} + 4z^{-2}} = \frac{2(1 + 2z^{-1} + z^{-2})}{4 + z^{-1} + z^{-2}} $$ 17. Circular Convolution & Comparison with Linear Convolution Circular Convolution: For $x[n] = [2, 1, 0]$ (length $N_x=3$) and $h[n] = [3, 4, 5]$ (length $N_h=3$). The length of the circular convolution $y_c[n]$ is $\max(N_x, N_h) = 3$. $y_c[n] = \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} x[k] h[(n-k) \pmod N]$ For $n=0$: $y_c[0] = x[0]h[0] + x[1]h[-1 \pmod 3] + x[2]h[-2 \pmod 3]$ $y_c[0] = x[0]h[0] + x[1]h[2] + x[2]h[1]$ $y_c[0] = 2 \cdot 3 + 1 \cdot 5 + 0 \cdot 4 = 6 + 5 + 0 = 11$ For $n=1$: $y_c[1] = x[0]h[1] + x[1]h[0] + x[2]h[-1 \pmod 3]$ $y_c[1] = x[0]h[1] + x[1]h[0] + x[2]h[2]$ $y_c[1] = 2 \cdot 4 + 1 \cdot 3 + 0 \cdot 5 = 8 + 3 + 0 = 11$ For $n=2$: $y_c[2] = x[0]h[2] + x[1]h[1] + x[2]h[0]$ $y_c[2] = 2 \cdot 5 + 1 \cdot 4 + 0 \cdot 3 = 10 + 4 + 0 = 14$ Result: $y_c[n] = [11, 11, 14]$ Difference between Circular and Linear Convolution: Feature Linear Convolution Circular Convolution Definition Standard convolution, $y[n] = \sum x[k]h[n-k]$ Convolution with indices wrapped modulo N, $y_c[n] = \sum x[k]h[(n-k) \pmod N]$ Length of Output $L_x + L_h - 1$ $\max(L_x, L_h)$ (or a specified N $\ge \max(L_x, L_h)$) Boundary Effects No wrap-around. Output length accounts for all possible overlaps. Wrap-around effects (aliasing in time domain). Elements at the end of one sequence contribute to the beginning of the output. Domain Time-domain operation. Corresponds to multiplication of Z-transforms. Time-domain operation. Corresponds to multiplication of DFTs. DFT Relationship Aperiodic convolution. $Y(z) = X(z)H(z)$. Periodic convolution. $DFT(y_c[n]) = DFT(x[n]) \cdot DFT(h[n])$. Importance of Circular Convolution: FFT-based Convolution: Circular convolution is directly computed when multiplying DFTs. To obtain linear convolution using FFTs, zero-padding is applied to both sequences to a length of at least $L_x + L_h - 1$. This is known as "overlap-add" or "overlap-save" methods. Periodic Signals: Naturally applies to signals that are periodic or assumed to be periodic within a finite window. Computational Efficiency: For long sequences, computing convolution via FFT (which involves circular convolution) is significantly faster than direct linear convolution ($O(N \log N)$ vs $O(N^2)$). Digital Filter Implementation: Used in block processing of long signals through FIR filters, where segments of the input are processed using FFTs.