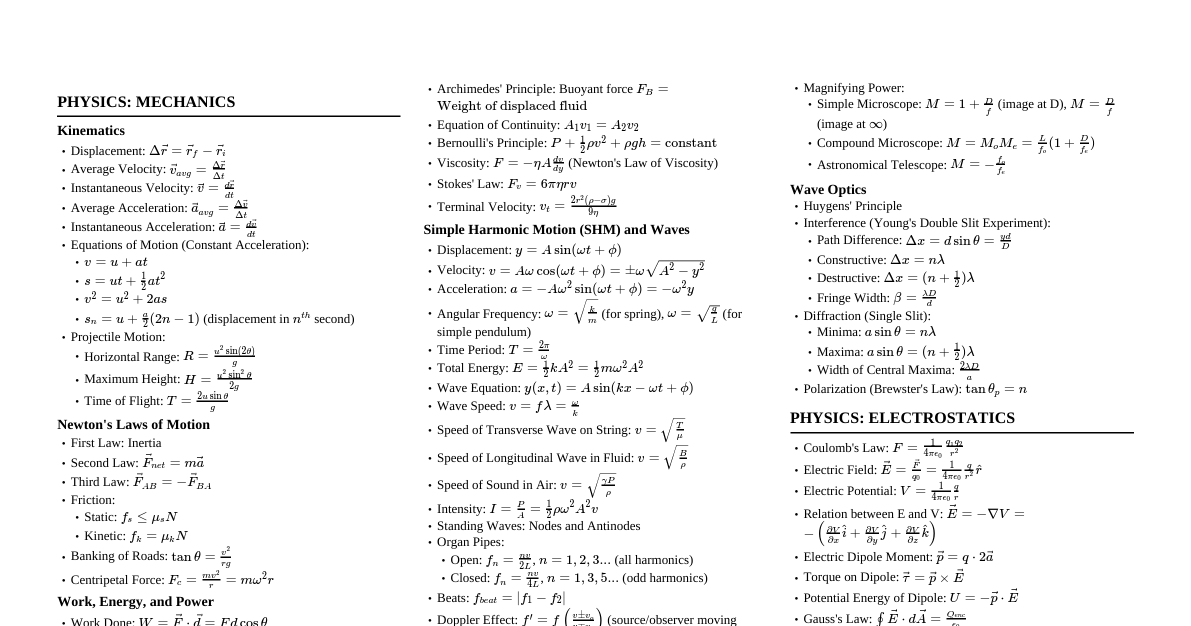

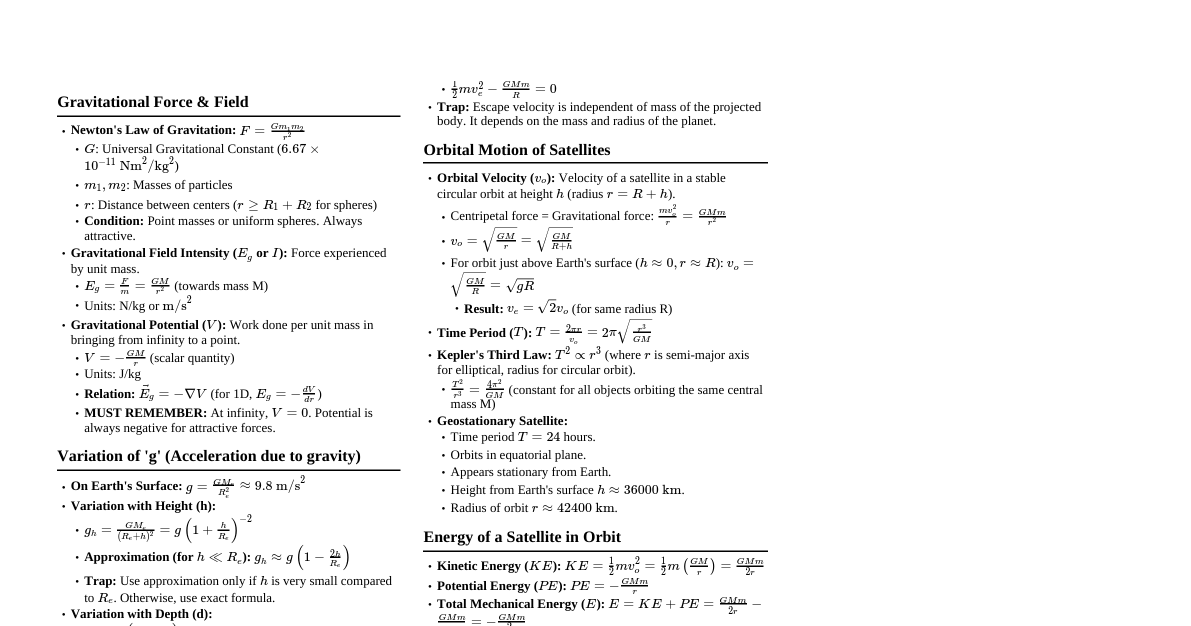

Universal Law of Gravitation (Newton) This fundamental law, proposed by Sir Isaac Newton, describes the attractive force that exists between any two objects with mass in the universe. It states that: Direct Proportionality to Masses: The gravitational force ($F$) is directly proportional to the product of the masses of the two objects ($m_1$ and $m_2$). This means if you double the mass of one object, the force doubles. If you double both masses, the force quadruples. Inverse Proportionality to Square of Distance: The gravitational force ($F$) is inversely proportional to the square of the distance ($r$) between their centers. This means if you double the distance between the objects, the force becomes one-fourth ($1/2^2$). If you halve the distance, the force becomes four times stronger ($1/(1/2)^2$). Mathematical Formulation: The law is expressed by the formula: $$F = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}$$ $F$: The magnitude of the gravitational force between the two objects. Measured in Newtons (N). $G$: The Universal Gravitational Constant. This is a fundamental constant of nature that determines the strength of the gravitational interaction. Its value is approximately $6.674 \times 10^{-11} \text{ Nm}^2/\text{kg}^2$. This value is extremely small, which is why gravity is only noticeable when at least one of the masses involved is very large (like a planet). $m_1, m_2$: The masses of the two interacting objects. Measured in kilograms (kg). $r$: The distance between the centers of mass of the two objects. Measured in meters (m). It's crucial to measure from the center, especially for spherical objects like planets. Example: The Earth attracts a falling apple, and the apple simultaneously attracts the Earth with an equal and opposite force. However, due to the Earth's enormous mass, its acceleration is negligible, while the apple's acceleration is significant. Mass vs. Weight: A Crucial Distinction These two terms are often used interchangeably in everyday language, but in physics, they represent very different physical quantities. Mass ($m$): Definition: Mass is a measure of the amount of matter (or "stuff") contained within an object. It's also a measure of an object's inertia – its resistance to changes in its state of motion. Nature: It is a scalar quantity , meaning it only has magnitude (e.g., 5 kg) and no direction. Unit: The standard international (SI) unit for mass is the kilogram (kg) . Constancy: The mass of an object is an intrinsic property and remains constant regardless of its location in the universe (e.g., an astronaut has the same mass on Earth as on the Moon). Weight ($W$): Definition: Weight is the force exerted on an object due to gravity. It's essentially the gravitational force attracting an object towards the center of a massive body (like Earth). Nature: It is a vector quantity , meaning it has both magnitude and direction (always pointing towards the center of the gravitating body). Unit: Since weight is a force, its SI unit is the Newton (N) . Variability: Weight is not constant ; it depends on the local acceleration due to gravity ($g$). An object will weigh less on the Moon than on Earth because the Moon's gravity is weaker. In deep space, far from any massive object, an object would be "weightless" (though still possessing mass). Formula: Weight is calculated as the product of an object's mass and the acceleration due to gravity at its location: $$W = m \times g$$ Where $m$ is mass (kg) and $g$ is acceleration due to gravity ($\text{m/s}^2$). Acceleration Due to Gravity ($g$) This is a specific case of gravitational acceleration, usually referring to the acceleration an object experiences near the surface of a planet or celestial body. Definition: It is the acceleration experienced by an object when it is falling freely under the sole influence of gravity, ignoring air resistance. Value on Earth: Near the Earth's surface, the average value of $g$ is approximately $9.8 \text{ m/s}^2$. This means that for every second an object falls, its downward velocity increases by $9.8 \text{ m/s}$. Formula Derivation: We can derive the formula for $g$ using Newton's Law of Gravitation. Consider an object of mass $m$ on the surface of a planet of mass $M$ and radius $R$. The gravitational force on the object is $F = G \frac{Mm}{R^2}$. By Newton's second law, this force also equals $F = ma = mg$. Equating these two expressions for force: $$mg = G \frac{Mm}{R^2}$$ The mass of the object, $m$, cancels out, leaving: $$g = G \frac{M}{R^2}$$ This shows that $g$ depends only on the mass and radius of the planet, not on the mass of the falling object. Factors Affecting $g$: Altitude (Height): As you move further away from the center of the Earth (i.e., increase altitude), $r$ in the universal gravitation formula increases. Since $g$ is inversely proportional to $r^2$, $g$ decreases with increasing altitude. That's why satellites experience slightly lower gravity. Depth: As you go inside the Earth (e.g., down a mine shaft), the mass $M$ attracting you decreases (only the mass within a sphere of radius $r$ below you contributes to the gravitational force). Thus, $g$ also decreases with increasing depth from the surface, becoming zero at the Earth's center. Shape of Earth: The Earth is not a perfect sphere; it bulges at the equator and is flattened at the poles. This means the radius $R$ is slightly larger at the equator than at the poles. As $g$ is inversely proportional to $R^2$, $g$ is slightly less at the equator and slightly more at the poles . Rotation of Earth: The Earth's rotation creates a slight centrifugal effect that opposes gravity, especially at the equator. This also contributes to $g$ being slightly less at the equator. Free Fall Free fall is a simplified model of motion where an object is moving solely under the influence of gravity. Definition: An object is said to be in free fall if the only force acting upon it is gravity. In reality, this means neglecting air resistance. Key Principle: In a vacuum (where there's no air resistance), all objects, regardless of their mass, shape, or size, fall with the same constant acceleration, which is $g$. This was famously demonstrated by Galileo Galilei. A feather and a bowling ball dropped simultaneously in a vacuum chamber will hit the ground at the same time. Equations of Motion for Free Fall: Since free fall is a case of uniformly accelerated motion, we can use the standard kinematic equations, replacing the general acceleration 'a' with 'g'. Velocity-Time Relation: $v = u + gt$ $v$: Final velocity (m/s) $u$: Initial velocity (m/s) $g$: Acceleration due to gravity ($\text{m/s}^2$) $t$: Time (s) Position-Time Relation: $h = ut + \frac{1}{2}gt^2$ $h$: Displacement or height fallen (m) Velocity-Position Relation: $v^2 = u^2 + 2gh$ Sign Convention: When an object is falling downwards, $g$ is usually taken as positive (e.g., $+9.8 \text{ m/s}^2$). When an object is thrown upwards, gravity acts downwards, opposing the motion. In this case, $g$ is taken as negative (e.g., $-9.8 \text{ m/s}^2$) in the equations if upward direction is positive. Alternatively, you can use positive $g$ and ensure that initial velocity 'u' is positive for upward motion, and the final displacement 'h' will indicate direction. Thrust and Pressure These concepts are crucial for understanding how forces are distributed over surfaces, especially in fluids. Thrust: Definition: Thrust is the total force acting perpendicularly (at a right angle) to a surface. Nature: It is a force, so it is a vector quantity. Unit: Like any force, its SI unit is the Newton (N) . Example: If you push down on a table with your hand, the force you apply perpendicular to the table's surface is thrust. Pressure ($P$): Definition: Pressure is defined as the thrust (perpendicular force) acting per unit area. It tells us how concentrated a force is. Formula: $$P = \frac{\text{Thrust}}{\text{Area}} = \frac{F}{A}$$ Where $F$ is the perpendicular force (N) and $A$ is the area over which the force is distributed ($\text{m}^2$). Unit: The SI unit for pressure is the Pascal (Pa) , which is equivalent to one Newton per square meter ($\text{N/m}^2$). Key Relationship: For a given force, pressure is inversely proportional to the area. Small Area $\rightarrow$ High Pressure: This is why a sharp knife cuts easily (force concentrated on a tiny area), or why a nail has a sharp point (to exert high pressure and penetrate wood). Large Area $\rightarrow$ Low Pressure: This is why snowshoes prevent sinking into snow (force distributed over a large area), or why wide shoulder straps on bags are more comfortable than thin ones. Pressure in Fluids (Liquids and Gases) Fluids behave differently from solids when it comes to exerting pressure. Direction of Pressure: Fluids exert pressure in all directions at any given depth. This is why a submerged object experiences pressure from all sides. Pressure due to a Liquid Column: The pressure exerted by a column of liquid at a certain depth is given by: $$P = h \rho g$$ $h$: The height (or depth) of the liquid column above the point of measurement. Measured in meters (m). $\rho$ (rho): The density of the liquid. Measured in kilograms per cubic meter ($\text{kg/m}^3$). $g$: The acceleration due to gravity ($\text{m/s}^2$). Key Implications: Pressure increases with depth: As $h$ increases, $P$ increases. This is why divers experience greater pressure at greater depths. Pressure depends on density: Denser liquids exert more pressure at the same depth. Pressure is independent of the shape of the container: At the same depth, the pressure will be the same in containers of different shapes, as long as they contain the same liquid. Buoyancy and Archimedes' Principle These concepts explain why objects float or sink in fluids. Buoyancy (Upthrust): Definition: Buoyancy is the upward force exerted by a fluid on an object that is wholly or partially immersed in it. This force opposes the weight of the object. Cause: It arises because the pressure at the bottom of a submerged object is greater than the pressure at the top (due to increasing depth), creating a net upward force. Archimedes' Principle: This principle provides a quantitative way to calculate the buoyant force. Statement: When an object is wholly or partially immersed in a fluid, it experiences an upthrust (buoyant force) that is equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the immersed part of the object. Mathematical Formulation: $$\text{Buoyant Force } (F_B) = \text{Weight of fluid displaced}$$ Since weight = mass $\times$ gravity, and mass = density $\times$ volume, we can write: $$F_B = V_{displaced} \times \rho_{fluid} \times g$$ $V_{displaced}$: The volume of the fluid that is pushed aside (displaced) by the immersed part of the object. Measured in cubic meters ($\text{m}^3$). $\rho_{fluid}$: The density of the fluid (liquid or gas) in which the object is immersed. Measured in kilograms per cubic meter ($\text{kg/m}^3$). $g$: The acceleration due to gravity ($\text{m/s}^2$). Conditions for Floating or Sinking: If the Buoyant Force ($F_B$) is greater than the Weight of the object ($W_{obj}$), the object will float , with only a portion submerged until $F_B = W_{obj}$. If the Buoyant Force ($F_B$) is less than the Weight of the object ($W_{obj}$), the object will sink . If the Buoyant Force ($F_B$) is equal to the Weight of the object ($W_{obj}$), the object will float, fully submerged (or just at the surface, neither rising nor sinking). Density-based Floating/Sinking: A simpler rule to predict floating or sinking: An object will float if its average density is less than the density of the fluid. An object will sink if its average density is greater than the density of the fluid. An object will remain suspended (float fully submerged) if its average density is equal to the density of the fluid. Relative Density (Specific Gravity) Relative density is a convenient way to compare the density of a substance to a reference substance. Definition: It is the ratio of the density of a substance to the density of a reference substance, which is usually water at $4^\circ \text{C}$ (where its density is approximately $1000 \text{ kg/m}^3$ or $1 \text{ g/cm}^3$). Formula: $$\text{Relative Density} = \frac{\text{Density of substance}}{\text{Density of water}}$$ Nature: Relative density is a dimensionless quantity , meaning it has no units, as it is a ratio of two densities whose units cancel out. Practical Use: If a substance has a relative density of 2, it means it is twice as dense as water. If it has a relative density of 0.8, it is 0.8 times as dense as water and will float.