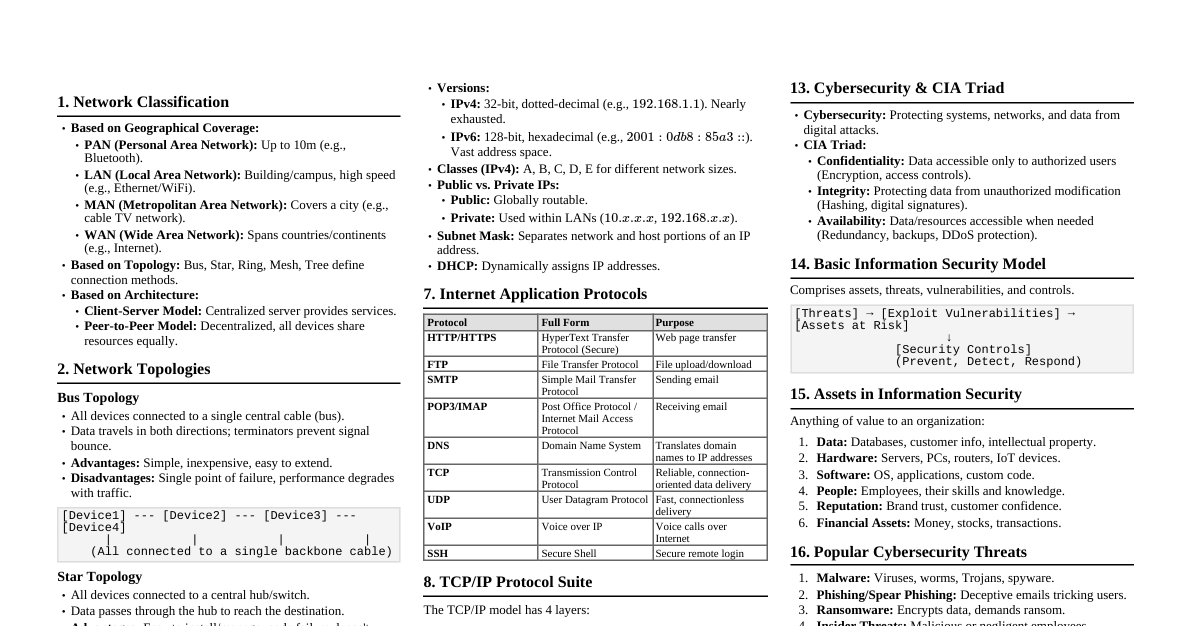

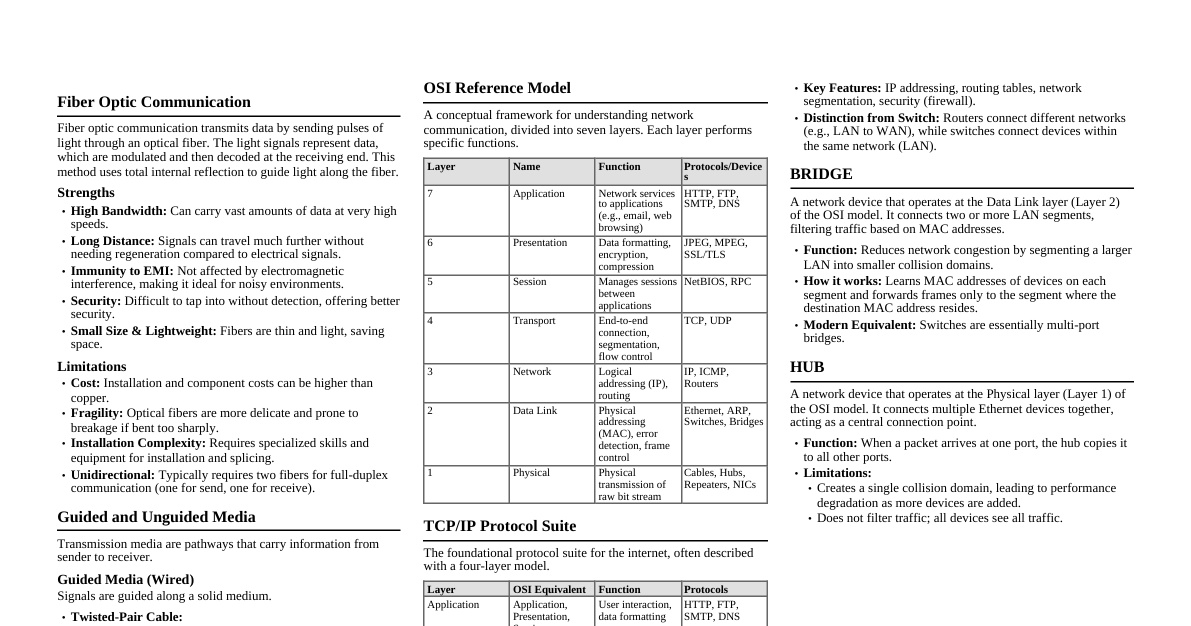

Data Communication Overview Data communication is the process of transferring digital information (data) between two or more computing devices or nodes. This transfer can be local or remote, occurring over various types of transmission media. Characteristics of Data Communication Delivery: Data must be delivered to the correct destination. Accuracy: Data must be delivered accurately, without alteration. Timeliness: Data must be delivered in a timely manner. For real-time applications, late data is useless. Jitter: Variation in packet arrival time. It is the uneven delay in the delivery of audio or video packets. Components of Data Communication Component Description Message The information (data) to be communicated. This can be text, numbers, pictures, audio, or video. Sender The device that initiates the data message. Examples: computers, workstations, telephones, video cameras. Receiver The device that receives the data message. Examples: computers, workstations, telephones, video cameras. Medium The physical path over which the message travels from sender to receiver. Examples: twisted-pair wire, coaxial cable, fiber-optic cable, radio waves (wireless). Protocol A set of rules that govern data communication. It dictates how data is formatted, transmitted, received, and error-checked. Without a protocol, two devices may be connected but cannot communicate. Data Flow Types Simplex: Communication is unidirectional. Only one device can transmit, the other can only receive. Example: Radio broadcast, traditional television. Half-Duplex: Communication is bidirectional, but not simultaneously. Devices can transmit and receive, but not at the same time. Example: Walkie-talkie. Full-Duplex: Communication is bidirectional simultaneously. Both devices can transmit and receive at the same time. Example: Telephone conversation. Network Topologies The physical or logical arrangement of connected nodes in a network. Bus Topology Node Node Node Node Node Description: All devices are connected to a single central cable (backbone). Data travels along the backbone, and each node checks if the data is for it. Advantages: Easy to install and expand. Requires less cabling than Star or Mesh. Cost-effective for small networks. Disadvantages: Single point of failure (if the backbone cable breaks, the entire network goes down). Difficult to troubleshoot individual device problems. Performance degrades with heavy network traffic and more devices. Limited cable length and number of devices. Star Topology Hub Description: Each device is connected to a central hub, switch, or server. Communication between any two devices must pass through the central device. Advantages: Easy to install and reconfigure (add/remove devices). Fault isolation: Failure of one device or its cable doesn't affect others. Easy to detect and troubleshoot faults. Better performance than Bus under heavy load. Disadvantages: The central device is a single point of failure (if it fails, the entire network goes down). Requires more cabling than Bus. Cost can increase with the number of ports on the central device. Ring Topology Description: Devices are connected in a closed loop, with each device connected to exactly two other devices. Data travels in one direction around the ring. Advantages: Ordered access: Each device gets a turn to transmit, avoiding collisions. Good performance under heavy network load (token passing). No terminators required. Disadvantages: Single point of failure: A break in the cable or failure of one device can disrupt the entire network. Difficult to add or remove devices as it requires temporarily shutting down the network. Troubleshooting can be complex. Mesh Topology Description: Every device is connected to every other device in the network via a dedicated point-to-point link. Advantages: High redundancy and fault tolerance: If one link fails, data can take an alternative path. Robust and secure communication. No traffic problems (dedicated links). Easy to diagnose faults. Disadvantages: Very expensive and complex to implement due to extensive cabling. Difficult to install and reconfigure (adding new devices is complex). Requires many I/O ports on each device. Not practical for large networks. Hybrid Topology Description: A combination of two or more different topologies (e.g., Star-Bus, Star-Ring). Advantages: Inherits the strengths of the combined topologies. Flexible and scalable for large networks. Optimized for specific requirements. Disadvantages: More complex to design, install, and manage. Can be more expensive. OSI Model vs. TCP/IP Model Comparison Both models describe how data is transmitted over a network, but they differ in their structure, purpose, and historical development. Feature OSI Model (Open Systems Interconnection) TCP/IP Model (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol) Origin Developed by ISO (International Organization for Standardization) in the late 1970s. Academic, theoretical. Developed by DoD (U.S. Department of Defense) in the 1970s. Practical, Internet's foundation. Layers 7 Layers: Application Presentation Session Transport Network Data Link Physical 4 Layers (sometimes 5): Application (Combines OSI Application, Presentation, Session) Transport (Corresponds to OSI Transport) Internet (Corresponds to OSI Network) Network Access (Combines OSI Data Link and Physical) (Some models split Network Access into Data Link and Physical, making it 5 layers). Approach A conceptual model providing a clear distinction between services, interfaces, and protocols. Protocol-independent. A protocol suite model. The protocols themselves were developed first, then the model. Protocol-dependent. Implementation Less widely implemented as a complete stack. Used primarily as a reference tool for understanding network functions. The basis for the Internet and most modern networks. Widely implemented and practical. Strictness Strict adherence to layer definitions and functionality. More flexible, some layers can be combined or their functions overlap. Reliability Can be connection-oriented or connectionless at the Transport layer. Offers both connection-oriented (TCP) and connectionless (UDP) services at the Transport layer. Protocols Protocols are defined after the layers. Examples: X.25, ISDN. Protocols are built into the model. Examples: TCP, UDP, IP, HTTP, FTP, SMTP. TCP/IP Model Layers and Responsibilities The TCP/IP model simplifies the OSI model into four or five layers, focusing on practical implementation for the Internet. 1. Application Layer Corresponds to: OSI Application, Presentation, and Session Layers. Responsibility: This layer is closest to the end-user. It enables applications to access network services and defines the protocols that applications use to exchange data. It handles data formatting, encryption, and session management for applications. Key Protocols: HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol): For web browsing. FTP (File Transfer Protocol): For transferring files. SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol): For sending email. DNS (Domain Name System): Translates domain names to IP addresses. Telnet/SSH: For remote terminal access. SNMP (Simple Network Management Protocol): For network device management. 2. Transport Layer Corresponds to: OSI Transport Layer. Responsibility: Provides end-to-end communication between applications running on different hosts. It handles data segmentation (breaking data into smaller units), flow control, error control, and multiplexing/demultiplexing of application data to/from the network. Key Protocols: TCP (Transmission Control Protocol): Connection-oriented: Establishes a connection before data transfer. Reliable: Guarantees delivery, retransmits lost segments, ensures data arrives in order. Flow control: Prevents a fast sender from overwhelming a slow receiver. Congestion control: Manages network traffic to avoid congestion. Used by: HTTP, FTP, SMTP. UDP (User Datagram Protocol): Connectionless: No prior connection setup. Unreliable: Does not guarantee delivery or order; no retransmission. Faster and lower overhead than TCP. Used by: DNS, VoIP, video streaming. 3. Internet Layer (Network Layer) Corresponds to: OSI Network Layer. Responsibility: Responsible for logical addressing (IP addresses) and routing packets across different networks. It defines how data packets are sent from a source host to a destination host, potentially across multiple networks. Key Protocols: IP (Internet Protocol): Primary protocol for addressing and routing. Connectionless and unreliable packet delivery. IP addresses uniquely identify devices on the network. IPv4: 32-bit addresses (e.g., 192.168.1.1). IPv6: 128-bit addresses, designed to replace IPv4. ICMP (Internet Control Message Protocol): Used for error reporting and diagnostic functions (e.g., ping). ARP (Address Resolution Protocol): Maps IP addresses to MAC addresses. 4. Network Access Layer (Host-to-Network Layer) Corresponds to: OSI Data Link and Physical Layers. Responsibility: This layer combines the functions of the OSI Data Link and Physical layers. It defines how data is physically transmitted over the network medium. It handles physical addressing (MAC addresses), framing, error detection at the local link, and the electrical/optical/radio characteristics of the transmission medium. Key Protocols/Technologies: Ethernet: Most common wired LAN technology. Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11): Wireless LAN technology. Token Ring, FDDI, PPP, Frame Relay: Other link-layer technologies. Physical specifications of cables (twisted pair, fiber optic), connectors, and signaling methods. Logical Connection in TCP/IP In the context of TCP/IP, a "logical connection" refers to the end-to-end communication path between two applications or processes. This virtual connection provides an illusion of a direct link, even though data may traverse many intermediate physical devices and networks. The TCP protocol at the Transport Layer is primarily responsible for establishing and maintaining these reliable logical connections. How TCP Establishes a Logical Connection (3-Way Handshake) TCP uses a three-way handshake process to establish a reliable, full-duplex logical connection: SYN (Synchronization) - Step 1: The client (initiator) sends a SYN segment to the server. This segment includes a randomly generated initial sequence number (ISN) for the data stream the client expects to send. SYN-ACK (Synchronization-Acknowledgement) - Step 2: The server receives the SYN segment and, if it accepts the connection, responds with a SYN-ACK segment. This segment contains the server's own ISN and an acknowledgment number (ACK) that confirms receipt of the client's SYN (typically client's ISN + 1). ACK (Acknowledgement) - Step 3: The client receives the SYN-ACK segment and sends an ACK segment to the server. This segment acknowledges the server's SYN (typically server's ISN + 1). At this point, the logical connection is fully established, and both client and server are ready to exchange data. Diagram: Logical vs. Physical Connection Client App TCP IP Server App TCP IP Router Router Physical Link Physical Link Physical Link Logical Connection (TCP) The Physical Connection (solid black lines) represents the actual hardware connections and data paths across the network infrastructure. Data packets traverse these physical links, often hop-by-hop between routers. The Logical Connection (dashed red line) illustrates the virtual, end-to-end communication channel maintained by TCP. From the perspective of the application, data flows directly between the client and server applications, even though physically it passes through multiple intermediate devices. Significance of Logical Connection (TCP) Reliability: Guarantees that data sent by the sender is received by the receiver completely, in order, and without errors. TCP handles retransmissions of lost packets, duplicate detection, and ordering. Flow Control: Prevents a fast sender from overwhelming a slower receiver by negotiating data transmission rates. Congestion Control: Adapts transmission rates to avoid network congestion, ensuring fair usage of network resources. Abstraction: Simplifies application development by hiding the complexities of network failures, packet loss, and routing from the application layer. Multiplexing/Demultiplexing: Uses port numbers to allow multiple applications on a single host to share the same physical network connection simultaneously. Transmission Media Guided Media (Wired) Twisted-Pair Cable: Twisted-pair cable is a type of wiring in which two insulated copper wires are twisted together. This twisting is crucial for minimizing electromagnetic interference (EMI) and crosstalk, which are common issues in data transmission. Construction Conductors: Typically consists of two solid or stranded copper wires, each individually insulated. The gauge of the wire (e.g., 22-26 AWG) affects its electrical properties. Twisting: The two wires in a pair are twisted around each other. Multiple such twisted pairs (usually 4 pairs for Ethernet) are then bundled together. Outer Jacket: The entire bundle is enclosed in an outer protective sheath, often made of PVC or LSZH (Low Smoke Zero Halogen) material. Principle of Interference Reduction The twisting mechanism is key to its effectiveness: Crosstalk Reduction: When current flows through one wire, it creates an electromagnetic field that can induce a signal in an adjacent wire (crosstalk). Twisting ensures that each wire in a pair is equally exposed to the field of the other wire, but in opposite directions along its length. This causes the induced signals to cancel each other out. External EMI/RFI Immunity: Similarly, external electromagnetic noise (from power lines, motors, etc.) induces currents in both wires of a twisted pair. Because the wires are twisted and close together, the induced noise currents are approximately equal and opposite, effectively canceling out the noise at the receiver's differential input. Twist Rate: Different pairs within the same cable are twisted at varying rates to prevent crosstalk between the pairs themselves. A higher twist rate generally provides better noise immunity but can increase cable cost and difficulty in termination. Types of Twisted Pair Cable 1. Unshielded Twisted Pair (UTP) Description: This is the most common type. It consists only of insulated twisted pairs within an outer jacket, with no additional metallic shielding. Advantages: Cost-Effective: Least expensive among guided media. Easy to Install: Flexible and smaller diameter, making it easy to work with. Widely Used: Standard for Ethernet LANs and telephone systems. Disadvantages: Susceptible to Interference: More prone to external electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio frequency interference (RFI) than shielded cables. Limited Distance: Performance degrades over longer distances, requiring repeaters. Categories (CAT ratings - based on IEEE 802.3 standards): Cat3: Up to 10 Mbps, primarily for voice communication (older telephone networks). Cat5/5e: Cat5 supports up to 100 Mbps (Fast Ethernet); Cat5e (enhanced) supports up to 1 Gbps (Gigabit Ethernet) over 100 meters. Cat6/6a: Cat6 supports 1 Gbps over 100m, and 10 Gbps over 55m. Cat6a (augmented) supports 10 Gbps over 100m. Features a separator between pairs to reduce crosstalk. Cat7/7a/8: Higher performance categories, supporting 10 Gbps and beyond (Cat8 for 25/40 Gbps) for specialized applications and data centers. 2. Shielded Twisted Pair (STP) Description: Incorporates a metallic shield (foil or braid) around the individual twisted pairs, or around the entire bundle of pairs, or both. This shield provides additional protection against EMI/RFI. Advantages: Superior Noise Immunity: Significantly reduces EMI/RFI and crosstalk compared to UTP. Higher Performance: Can support higher data rates and longer distances than UTP in noisy environments. Disadvantages: More Expensive: Due to additional materials and manufacturing complexity. Thicker and Less Flexible: Harder to install, especially in tight spaces. Grounding Requirement: The shield must be properly grounded to be effective; improper grounding can make it a source of noise. Applications: Industrial settings, environments with high electrical interference, and high-security networks. Connectors RJ-45 (Registered Jack 45): The standard modular connector used for terminating UTP and STP cables in Ethernet networks. RJ-11: A smaller version, commonly used for telephone connections (primarily Cat3 cable). Coaxial Cable: Better shielding than UTP, used for cable TV and older Ethernet. Fiber-Optic Cable: Transmits data using light signals. High bandwidth, long distances, immune to electromagnetic interference. Single-mode: For long distances. Multi-mode: For shorter distances. Unguided Media (Wireless) Radio Waves: Omnidirectional, used for broadcasting, WLANs, cellular. Microwaves: Unidirectional (line-of-sight), used for long-distance communication and satellite. Infrared: Short-range, line-of-sight, used for remote controls, limited by obstacles. Networking Devices Hub: Connects multiple devices in a network, broadcasts data to all ports. (Layer 1) Switch: Connects multiple devices, intelligently forwards data to the intended recipient. (Layer 2) Router: Connects different networks, forwards data packets between them. (Layer 3) Modem: Modulates/demodulates signals to enable data transmission over phone lines or cable. Repeater: Regenerates and extends network signals to cover longer distances. Bridge: Connects two LANs working on the same protocol. (Layer 2)