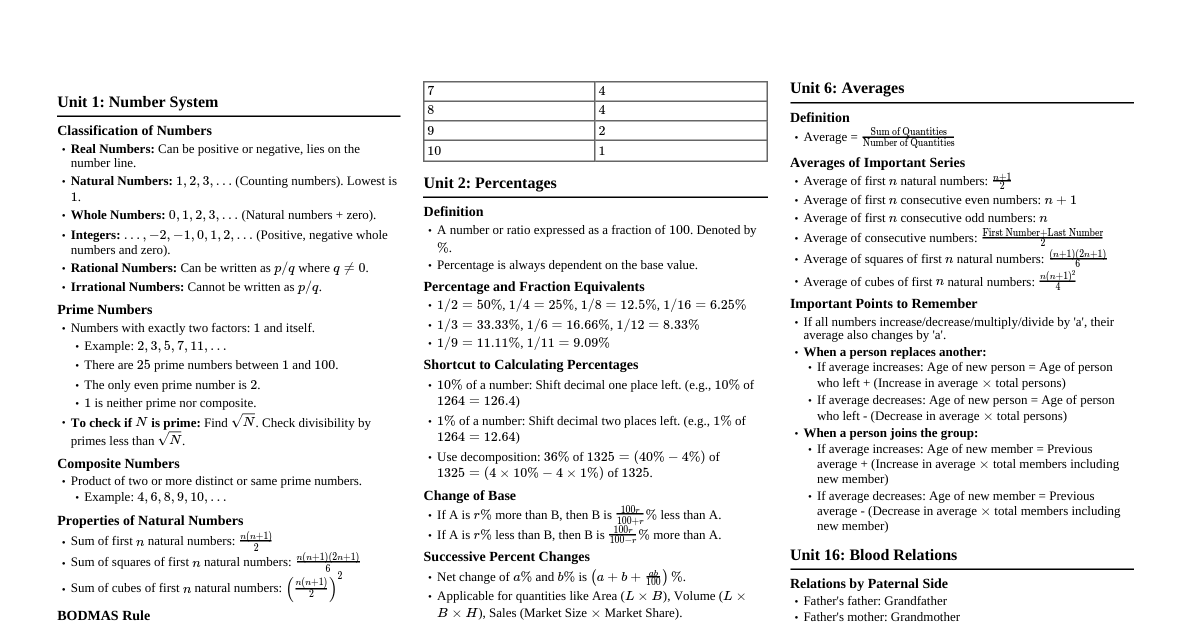

### Oxidation & Reduction A comparative study of oxidation and reduction reactions: | Oxidation | Reduction | |------------------------------------------|---------------------------------------| | (1) Addition of oxygen | (i) Removal of oxygen | | e.g., $2Mg + O_2 \rightarrow 2MgO$ | e.g., $CuO + C \rightarrow Cu + CO$ | | (2) Removal of Hydrogen | (ii) Addition of Hydrogen | | e.g., $H_2S + Cl_2 \rightarrow 2HCl + S$ | e.g., $S + H_2 \rightarrow H_2S$ | | (3) Increase in positive charge | (iii) Decrease in positive charge | | e.g., $Fe^{2+} \rightarrow Fe^{3+} + e^-$| e.g., $Fe^{3+} + e^- \rightarrow Fe^{2+}$| | (4) Increase in oxidation number | (iv) Decrease in oxidation number | | $(+2) \rightarrow (+4)$ SnCl$_2 \rightarrow$ SnCl$_4$ | $(+7) \rightarrow (+2)$ $MnO_4^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+}$ | | (5) Removal of electron | (v) Addition of electron | | e.g., $Sn^{2+} \rightarrow Sn^{4+} + 2e^-$ | e.g., $Fe^{3+} + e^- \rightarrow Fe^{2+}$ | ### Oxidation Number - It is an imaginary or apparent charge gained by an element when it goes from its elemental free state to combined state in molecules. - It is calculated on basis of an arbitrary set of rules. - It is a relative charge in a particular bonded state. #### Rules Governing Oxidation Number The following rules are helpful in calculating oxidation number of the elements in their different compounds. It is remembered that the basis of these rules is the electronegativity of the element. - **Fluorine atom**: Fluorine is the most electronegative atom (known). It always has an oxidation number equal to -1 in all its compounds. - **Oxygen atom**: In general and as well as in its oxides, the oxygen atom has an oxidation number equal to -2. - In case of: - (i) peroxide (e.g., $H_2O_2$, $Na_2O_2$) is -1 - (ii) super oxide (e.g., $KO_2$) is -1/2 - (iii) ozonide ($KO_3$) is -1/3 - (iv) oxygen fluoride $OF_2$ is +2 & in $O_2F_2$ is +1 - **Hydrogen atom**: In general, H atom has oxidation number equal to +1. But in metallic hydrides (e.g., NaH, KH) it is -1. - **Halogen atom**: In general, all halogen atoms (Cl, Br, I) have an oxidation number equal to -1. - But if a halogen atom is attached with a more electronegative atom than the halogen atom then it will show positive oxidation numbers. - e.g., $K\stackrel{+5}{Cl}O_3$, $H\stackrel{+5}{I}O_3$, $H\stackrel{+7}{Cl}O_4$, $K\stackrel{+5}{Br}O_3$ - **Metals**: - (a) Alkali metal (Li, Na, K, Rb, ..........) always have oxidation number +1. - (b) Alkaline earth metal (Be, Mg, Ca ........) always have oxidation number +2. - (c) Aluminium always has a +3 oxidation number. - Oxidation number of an element in free state or in allotropic forms is always zero. - e.g., $O_2^{0}$, $S_8^{0}$, $P_4^{0}$, $O_3^{0}$ - The sum of the charges of elements in a molecule is zero. - The sum of the charges of all elements in an ion is equal to the charge on the ion. - If the group no. of an element in the periodic table is n then its oxidation number may vary from n to $(n-8)$ (but it is mainly applicable in p-block elements). - N-atom belongs to group V in the periodic table therefore as per rule its oxidation number may vary from -3 to +5 (e.g., $N^{-3}H_3$, $N^{0}O$, $N^{+3}_2O_3$, $N^{+4}O_2$, $N^{+5}_2O_5$). #### Calculation of Average Oxidation Number **Solved Examples:** **Ex:** Calculate oxidation number of underlined element $Na_2\underline{S}_2O_3$: **Sol.** Let oxidation number of S-atom is x. $(+1)2 + (x)2 + (-2)3 = 0$ $2 + 2x - 6 = 0$ $2x = 4 \Rightarrow x = +2$ **Ex:** $Na_2\underline{S}_4O_6$: **Sol.** Let oxidation number of S-atom is x. $(+1)2 + (x)4 + (-2)6 = 0$ $2 + 4x - 12 = 0$ $4x = 10 \Rightarrow x = +2.5$ It's important to note here that $Na_2S_2O_3$ has two S-atoms and there are four S-atoms in $Na_2S_4O_6$, but none of the sulfur atoms in both compounds have +2 or +2.5 oxidation numbers; this is the average charge (O. No.). To get the realistic picture, we should calculate the individual oxidation number of each sulfur atom in these compounds. **Ex:** Calculate the O.S. of all the atoms in the following species: (i) $ClO^-$, (ii) $NO_2^-$, (iii) $NO_3^-$, (iv) $CCl_4$, (v) $K_2CrO_4$ and (vi) $KMnO_4$ **Sol.** (i) In $ClO^-$, the net charge on the species is -1 and therefore the sum of the oxidation states of Cl and O must be equal to -1. Oxygen will have an O.S. of -2 and if the O.S. of Cl is assumed to be 'x' then $x - 2 = -1$. $x = +1$ (ii) $NO_2^-$: $x + (2 \times -2) = -1$ (where 'x' is O.S. of N) $x - 4 = -1 \Rightarrow x = +3$ (iii) $NO_3^-$: $x + (3 \times -2) = -1$ (where 'x' is O.S. of N) $x - 6 = -1 \Rightarrow x = +5$ (iv) In $CCl_4$, Cl has an O.S. of -1 $x + (4 \times -1) = 0$ (where 'x' is O.S. of C) $x - 4 = 0 \Rightarrow x = +4$ (v) $K_2CrO_4$: K has O.S. of +1 and O has O.S. of -2 and let Cr has O.S. 'x' then, $(2 \times +1) + x + (4 \times -2) = 0$ $2 + x - 8 = 0 \Rightarrow x = +6$ (vi) $KMnO_4$: $+1 + x + (4 \times -2) = 0$ (where x is O.S. of Mn). $+1 + x - 8 = 0 \Rightarrow x = +7$ ### Miscellaneous Examples In order to determine the exact or individual oxidation number we need to take help from the structures of the molecules. Some special cases are discussed as follows: - The structure of $CrO_5$ is: ``` O / \ O---O / | \ O---Cr---O \ / O ``` From the structure it is evident that in $CrO_5$ there are two peroxide linkages and one double bond. The contribution of each peroxide linkage is -2. Let the O.N. of Cr is x. $x + (-2)2 + (-2) = 0 \Rightarrow x = +6$ O.N. of Cr = +6. - The structure of $H_2SO_5$ is $H-O-O-S(=O)_2-O-H$ From the structure, it is evident that in $H_2SO_5$, there is one peroxide linkage, two sulfur-oxygen double bonds and one OH group. Let the O.N. of S = x. $(+1)2 + (-2) + x + (2 \times -2) + (-2) + (+1) = 0$ $2 - 2 + x - 4 - 2 + 1 = 0 \Rightarrow x - 5 = 0 \Rightarrow x = +6$ O.N. of S in $H_2SO_5$ is +6. #### Paradox of Fractional Oxidation Number Fractional oxidation state is the average oxidation state of the element under examination and the structural parameters reveal that the element for whom fractional oxidation state is realized is actually present in different oxidation states. Structures of the species $C_3O_2$, $Br_3O_8$ and $S_4O_6^{2-}$ reveal the following bonding situations: - The element marked with an asterisk in each species is exhibiting a different oxidation state (oxidation number) from the rest of the atoms of the same element in each of the species. This reveals that in $C_3O_2$, two carbon atoms are present in +2 oxidation state each whereas the third one is present in zero oxidation state and the average is 4/3. However the realistic picture is +2 for two terminal carbons and zero for the middle carbon. $O = \stackrel{+2}{C} = \stackrel{0}{C}^* = \stackrel{+2}{C} = O$ Structure of $C_3O_2$ (Carbon suboxide) - Likewise in $Br_3O_8$, each of the two terminal bromine atoms are present in +6 oxidation state and the middle bromine is present in +4 oxidation state. Once again the average, that is different from reality is 16/3. $O = \stackrel{+6}{Br} - \stackrel{+4}{Br}^* - \stackrel{+6}{Br} = O$ Structure of $Br_3O_8$ (tribromooctaoxide) - In the same fashion, in the species $S_4O_6^{2-}$, the average oxidation state of sulfur is 2.5, whereas the reality being +5, 0, 0 and +5 oxidation numbers respectively for each sulfur. ``` O O || || -O-S-S-S-S-O- || || O O ``` Structure of $S_4O_6^{2-}$ (tetrathionate ion) ### Oxidising and Reducing Agent #### Oxidising agent or Oxidant - Oxidising agents are those compounds which can oxidise others and reduce themselves during the chemical reaction. Those reagents whose O.N. decrease or which gain electrons in a redox reaction are termed as oxidants. - e.g., $KMnO_4$, $K_2Cr_2O_7$, $HNO_3$, conc. $H_2SO_4$ etc., are powerful oxidising agents. #### Reducing agent or Reductant - Reducing agents are those compounds which can reduce others and oxidise themselves during the chemical reaction. Those reagents whose O.N. increase or which lose electrons in a redox reaction are termed as reductants. - e.g., KI, $Na_2S_2O_3$ are powerful reducing agents. **Note:** There are some compounds also which can work both as oxidising agent and reducing agent. - e.g., $H_2O_2$, $NO_2$ #### How to Identify Whether a Particular Substance is an Oxidising or Reducing Agent 1. Find the O. State of the central atom. 2. If O.S. is Max. O.S. or (valence electron): It's an Oxidizing agent. 3. If O.S. = Minimum O.S.: It's a reducing agent. 4. If O.S. is intermediate b/w max & minimum: It can act both as a reducing agent & oxidising agent. It can disproportionate as well. ### Redox Reaction - A reaction in which oxidation and reduction simultaneously take place. - In all redox reactions the total increase in oxidation number must equal the total decrease in oxidation number. - e.g., $10\stackrel{+2}{Fe}SO_4 + 2\stackrel{+7}{K}MnO_4 + 8H_2SO_4 \rightarrow 5\stackrel{+3}{Fe}_2(SO_4)_3 + 2\stackrel{+2}{Mn}SO_4 + K_2SO_4 + 8H_2O$ #### Disproportionation Reactions - A redox reaction in which the same element present in a particular compound in a definite oxidation state is oxidized as well as reduced simultaneously is a disproportionation reaction. - Disproportionation reactions are a special type of redox reactions. One of the reactants in a disproportionation reaction always contains an element that can exist in at least three oxidation states. The element in the form of reacting substance is in the intermediate oxidation state and both higher and lower oxidation states of that element are formed in the reaction. - e.g., $2\stackrel{-1}{H_2}\stackrel{+1}{O}_2 (aq) \rightarrow 2\stackrel{-2}{H_2}\stackrel{}{O} (l) + \stackrel{0}{O}_2(g)$ - e.g., $3\stackrel{0}{Cl}_2 (g) + 6OH^- (aq) \rightarrow 5\stackrel{-1}{Cl}^- (aq) + \stackrel{+5}{Cl}O_3^- (aq) + 3H_2O (l)$ In the above reaction, we can see that $Cl_2$ has been oxidized as well as reduced. Such type of redox reaction is called disproportionation reaction. #### Some More Examples - $2\stackrel{+1}{Cu}^+ \xrightarrow{\text{Disproportionates}} \stackrel{0}{Cu} + \stackrel{+2}{Cu}^{2+}$ - $2H\stackrel{0}{C}HO + OH^- \rightarrow C\stackrel{+1}{H}_3OH + H\stackrel{-1}{C}OO^-$ - $4\stackrel{0}{O}_3 \rightarrow 3\stackrel{0}{O}_2 + \stackrel{0}{O}_2$ (This is incorrect in the source, should be $4O_3 \rightarrow 6O_2$) - $3MnO_4^{2-} + 2H_2O \rightarrow MnO_2 + 2MnO_4^- + 4OH^-$ #### Consider following reactions - (a) $2KClO_3 = 2KCl + 3O_2$ $KClO_3$ plays a role of oxidant and reductant both. Because the same element is not oxidised and reduced. Here, Cl present in $KClO_3$ is reduced and O present in $KClO_3$ is oxidized. So it's not a disproportionation reaction although it looks like one. - (b) $NH_4NO_2 \rightarrow N_2 + 2H_2O$ Nitrogen in this compound has -3 and +3 oxidation number so it is not a definite value, so it's not a disproportionation reaction. It's an example of comproportionation reaction which is a class of redox reaction in which an element from two different oxidation states gets converted into a single oxidation state. - (c) $4KClO_3 \rightarrow 3KClO_4 + KCl$ It's a case of disproportionation reaction in which Cl is the atom disproportionating. #### List of Some Important Disproportionation Reactions 1. $H_2O_2 \rightarrow H_2O + O_2$ 2. $X_2 + OH^- (dil.) \rightarrow X^- + XO^-$ 3. $X_2 + OH^- (conc.) \rightarrow X^- + XO_3^-$ - $F_2$ does not (cannot) undergo disproportionation as it is the most electronegative element. - $F_2 + NaOH (dil) \rightarrow F^- + OF_2$ - $F_2 + NaOH concentration (dil) \rightarrow F^- + O_2$ - Reverse of disproportionation is called Comproportionation. In some of the disproportionation reactions by changing the medium (from acidic to basic or reverse) the reaction goes in backward direction and can be taken as an example of Comproportionation. - $I^- + IO_3^- + H^+ \rightarrow I_2 + H_2O$ (acidic) #### Some examples of redox reactions are - $Sn^{2+} + 2Hg^{2+} \rightarrow Hg_2^{2+} + Sn^{4+}$ - $MnO_4^- + 5Fe^{2+} + 8H^+ \rightarrow 5Fe^{3+} + Mn^{2+} + 4H_2O$ - $Cr_2O_7^{2-} + 6Fe^{2+} + 14H^+ \rightarrow 6Fe^{3+} + 2Cr^{3+} + 7H_2O$ - $3Cu + 2NO_3^- + 8H^+ \rightarrow 2NO + 3Cu^{2+} + 4H_2O$ - If one of the half reactions does not take place, the other half will also not take place. We can say oxidation and reduction go side by side. ### Balancing of Redox Reaction All balanced equations must satisfy two criteria: 1. **Atom balance (mass balance)**: That is there should be the same number of atoms of each kind in reactant and products side. 2. **Charge balance**: That is the sum of actual charges on both sides of the equation must be equal. There are two methods for balancing redox equations: (a) Oxidation - number change method (b) Ion electron method or half cell method #### Oxidation Number Change Method - This method was given by Jonson. In a balanced redox reaction, the total increase in oxidation number must be equal to the total decrease in oxidation number. This equivalence provides the basis for balancing redox reactions. - The general procedure involves the following steps: (i) Select the atom in the oxidising agent whose oxidation number decreases and indicate the gain of electrons. (ii) Select the atom in the reducing agent whose oxidation number increases and write the loss of electrons. (iii) Now cross multiply i.e. multiply the oxidising agent by the number of loss of electrons and the reducing agent by the number of gain of electrons. (iv) Balance the number of atoms on both sides whose oxidation numbers change in the reaction. (v) In order to balance oxygen atoms, add $H_2O$ molecules to the side deficient in oxygen. Then balance the number of H atoms by adding $H^+$ ions in the hydrogen. **Ex.** Balance the following reaction by the oxidation number method: $Cu + HNO_3 \rightarrow Cu(NO_3)_2 + NO_2 + H_2O$ **Sol.** Write the oxidation number of all the atoms. $\stackrel{0}{Cu} + H\stackrel{+5}{N}O_3 \rightarrow \stackrel{+2}{Cu}(NO_3)_2 + \stackrel{+4}{N}O_2 + H_2O$ There is a change in oxidation number of Cu and N. $\stackrel{0}{Cu} \rightarrow \stackrel{+2}{Cu}(NO_3)_2$ (Oxidation no. is increased by 2) ....(1) $H\stackrel{+5}{N}O_3 \rightarrow \stackrel{+4}{N}O_2$ (Oxidation no. is decreased by 1) ....(2) To make increase and decrease equal, eq. (2) is multiplied by 2. $Cu + 2HNO_3 \rightarrow Cu(NO_3)_2 + 2NO_2 + H_2O$ Balancing nitrate ions, hydrogen and oxygen, the following equation is obtained. $Cu + 4HNO_3 \rightarrow Cu(NO_3)_2 + 2NO_2 + 2H_2O$ This is the balanced equation. **Ex.** Write the skeleton equation for each of the following processes and balance them by ion electron method: (i) Permanganate ion oxidizes oxalate ions in acidic medium to carbon dioxide and gets reduced itself to $Mn^{2+}$ ions. (ii) Bromine and hydrogen peroxide react to give bromate ions and water. (iii) Chlorine reacts with base to form chlorate ion, chloride ion and water in acidic medium. **Sol.** (i) The skeleton equation for the process: $MnO_4^- + C_2O_4^{2-} + H^+ \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + CO_2 + H_2O$ **Step (1): Indicating oxidation number:** $\stackrel{+7}{Mn}O_4^- + \stackrel{+3}{C}_2O_4^{2-} \rightarrow \stackrel{+2}{Mn}^{2+} + \stackrel{+4}{C}O_2$ **Step (2): Writing oxidation and reduction half reaction:** $C_2O_4^{2-} \rightarrow 2CO_2$ (Oxidation half) $MnO_4^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+}$ (Reduction half) **Step (3): Adding electrons to make the difference in O.N.** $C_2O_4^{2-} \rightarrow 2CO_2 + 2e^-$ $MnO_4^- + 5e^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+}$ **Step (4): Balancing 'O' atom by adding $H_2O$ molecules** $C_2O_4^{2-} \rightarrow 2CO_2 + 2e^-$ (Already balanced) $MnO_4^- + 5e^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 4H_2O$ **Step (5): Balancing H atom by adding $H^+$ ions** $C_2O_4^{2-} \rightarrow 2CO_2 + 2e^-$ (Already balanced) $MnO_4^- + 5e^- + 8H^+ \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 4H_2O$ **Step (6): Multiply the oxidation half reaction by 2 and reduction half reaction by 5 to equalize the electrons lost and gained and add the two half reactions.** $[C_2O_4^{2-} \rightarrow 2CO_2 + 2e^-] \times 5$ $[MnO_4^- + 5e^- + 8H^+ \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 4H_2O] \times 2$ $5C_2O_4^{2-} \rightarrow 10CO_2 + 10e^-$ $2MnO_4^- + 10e^- + 16H^+ \rightarrow 2Mn^{2+} + 8H_2O$ Adding the two half reactions: $2MnO_4^- + 5C_2O_4^{2-} + 16H^+ \rightarrow 10CO_2 + 2Mn^{2+} + 8H_2O$ (ii) The skeleton equation for the given process is: $Br_2 + H_2O_2 \rightarrow BrO_3^- + H_2O$ (in acidic medium) **Step (1): Indicate the oxidation number of each atom** $\stackrel{0}{Br}_2 + H_2\stackrel{-1}{O}_2 \rightarrow \stackrel{+5}{Br}O_3^- + H_2\stackrel{-2}{O}$ Thus, Br and O changes their oxidation numbers. **Step (2): Write the oxidation and reduction half reaction.** $Br_2 \rightarrow 2BrO_3^-$ (Oxidation half) $H_2O_2 \rightarrow H_2O$ (Reduction half) **Step (3): Addition of electrons to make up for the difference in O.N.** $\stackrel{0}{Br}_2 \rightarrow 2\stackrel{+5}{Br}O_3^- + 10e^-$ $H_2\stackrel{-1}{O}_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2H_2\stackrel{-2}{O}$ **Step (4): Balance 'O' atoms by adding $H_2O$ molecules** $Br_2 + 6H_2O \rightarrow 2BrO_3^- + 10e^-$ $H_2O_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2H_2O$ (Already balanced) **Step (5): Equalize the electrons by multiplying the reduction half with 5 and add the two half reactions** $[Br_2 + 6H_2O \rightarrow 2BrO_3^- + 10e^- + 12H^+]$ (Error in source, should be $12H^+$ on left for O balance) $[H_2O_2 + 2e^- + 2H^+ \rightarrow 2H_2O] \times 5$ This part of the source material has errors in the balancing. Let's re-balance it correctly: Oxidation half: $Br_2 + 6H_2O \rightarrow 2BrO_3^- + 10e^- + 12H^+$ Reduction half: $H_2O_2 + 2H^+ + 2e^- \rightarrow 2H_2O$ (multiply by 5) $5H_2O_2 + 10H^+ + 10e^- \rightarrow 10H_2O$ Adding the two half reactions: $Br_2 + 6H_2O + 5H_2O_2 + 10H^+ \rightarrow 2BrO_3^- + 10H_2O + 12H^+$ $Br_2 + 5H_2O_2 \rightarrow 2BrO_3^- + 4H_2O + 2H^+$ (iii) The skeleton equation for the given process: $Cl_2 + OH^- \rightarrow Cl^- + ClO_3^- + H_2O$ **Step (1): Indicate the oxidation number of each atom** $\stackrel{0}{Cl}_2 + OH^- \rightarrow \stackrel{-1}{Cl}^- + \stackrel{+5}{Cl}O_3^- + H_2O$ Thus, chlorine is the only element which undergoes the change in oxidation number. It decreases its oxidation number from 0 to -1 and also increases its oxidation number from 0 to +5. **Step (2): Write the oxidation and reduction half reactions** $Cl_2 \rightarrow 2ClO_3^-$ (Oxidation half) $Cl_2 \rightarrow 2Cl^-$ (Reduction half) **Step (3): Add electrons to make up for the difference in O.N.** $Cl_2 \rightarrow 2ClO_3^- + 10e^-$ $Cl_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2Cl^-$ **Step (4): Balance O atoms by adding $H_2O$ molecules** $Cl_2 + 6H_2O \rightarrow 2ClO_3^- + 10e^- + 12H^+$ (Corrected from source) $Cl_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2Cl^-$ (Already balanced) **Step (5): Since medium is basic, balance H atoms by adding $H_2O$ molecules to the side falling short of H atoms and an equal number of $OH^-$ ions to the other side.** Oxidation half: $Cl_2 + 6H_2O + 12OH^- \rightarrow 2ClO_3^- + 10e^- + 12H_2O$ (Corrected from source) $Cl_2 + 12OH^- \rightarrow 2ClO_3^- + 10e^- + 6H_2O$ Reduction half: $Cl_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2Cl^-$ **Step (6): Multiply the reduction half reaction by 5 and add two half reactions.** $[Cl_2 + 12OH^- \rightarrow 2ClO_3^- + 10e^- + 6H_2O]$ $[Cl_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2Cl^-] \times 5$ $5Cl_2 + 10e^- \rightarrow 10Cl^-$ Adding the two half reactions: $Cl_2 + 12OH^- + 5Cl_2 \rightarrow 2ClO_3^- + 6H_2O + 10Cl^-$ $6Cl_2 + 12OH^- \rightarrow 2ClO_3^- + 10Cl^- + 6H_2O$ Divide by 2: $3Cl_2 + 6OH^- \rightarrow ClO_3^- + 5Cl^- + 3H_2O$ **Ex:** Balance the following redox reaction by the oxidation number method: $MnO_4^- + Fe^{2+} \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + Fe^{3+}$ **Sol:** Write the oxidation number of all the atoms. $\stackrel{+7}{Mn}O_4^- + \stackrel{+2}{Fe}^{2+} \rightarrow \stackrel{+2}{Mn}^{2+} + \stackrel{+3}{Fe}^{3+}$ Change in oxidation number has occurred in Mn and Fe. $\stackrel{+7}{Mn}O_4^- \rightarrow \stackrel{+2}{Mn}^{2+}$ (Decrement in oxidation no. by 5) ....(1) $\stackrel{+2}{Fe}^{2+} \rightarrow \stackrel{+3}{Fe}^{3+}$ (Increment in oxidation no. by 1) ....(2) To make increase and decrease equal, eq. (2) is multiplied by 5. $MnO_4^- + 5Fe^{2+} \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 5Fe^{3+}$ To balance oxygen, 4$H_2O$ are added to R.H.S. and to balance hydrogen, 8$H^+$ are added to L.H.S. $MnO_4^- + 5Fe^{2+} + 8H^+ \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 5Fe^{3+} + 4H_2O$ This is the balanced equation. **Ex.** Balance the following chemical reaction by oxidation number method and write their skeleton equation: (i) Chloride ions reduce manganese dioxide to manganese (II) ions in acidic medium and get itself oxidized to chlorine gas. (ii) The nitrate ions in acidic medium oxidize magnesium to $Mg^{2+}$ ions but itself gets reduced to nitrous oxide. **Sol.** (i) The skeleton equation for the given process is: $MnO_2 + Cl^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + Cl_2 + H_2O$ **Step (1): Assign oxidation numbers:** $\stackrel{+4}{Mn}O_2 + \stackrel{-1}{Cl}^- \rightarrow \stackrel{+2}{Mn}^{2+} + \stackrel{0}{Cl}_2 + H_2O$ **Step (2): Identify changes.** O.N. decreases by 2 per Mn ($\stackrel{+4}{Mn}O_2 \rightarrow \stackrel{+2}{Mn}^{2+}$) O.N. increases by 1 per Cl ($\stackrel{-1}{Cl}^- \rightarrow \stackrel{0}{Cl}_2$) **Step (3): Equalize the increase/decrease in O.N. by multiplying** $MnO_2$ by 1 and $Cl^-$ by 2. $MnO_2 + 2Cl^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + Cl_2 + H_2O$ **Step (4): Balance other atoms except H and O.** Here they are all balanced. **Step (5): Balance O atoms by adding $H_2O$ molecules to the side falling short of O atoms.** $MnO_2 + 2Cl^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + Cl_2 + H_2O + H_2O$ $MnO_2 + 2Cl^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + Cl_2 + 2H_2O$ **Step (6): Balance H atoms by adding $H^+$ ions to the side falling short of H atoms.** $MnO_2 + 2Cl^- + 4H^+ \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + Cl_2 + 2H_2O$ (ii) The skeleton equation for the given process is: $Mg + NO_3^- \rightarrow Mg^{2+} + N_2O + H_2O$ **Step (1): Assign oxidation numbers:** $\stackrel{0}{Mg} + \stackrel{+5}{N}O_3^- \rightarrow \stackrel{+2}{Mg}^{2+} + \stackrel{+1}{N}_2O + H_2O$ Multiply $NO_3^-$ by 2 to equalize N atoms. **Step (2): Identify changes.** O.N. increases by 2 per Mg atom ($\stackrel{0}{Mg} \rightarrow \stackrel{+2}{Mg}^{2+}$) O.N. decreases by 4 per N atom (from $\stackrel{+5}{N}$ in $NO_3^-$ to $\stackrel{+1}{N}$ in $N_2O$, for $N_2O$ the total decrease is $2 \times (5-1) = 8$) **Step (3): Equalize increase/decrease in O.N. by multiplying Mg by 4 and $2NO_3^-$ by 1.** $4Mg + 2NO_3^- \rightarrow Mg^{2+} + N_2O + H_2O$ (Still need to balance Mg on product side) $4Mg + 2NO_3^- \rightarrow 4Mg^{2+} + N_2O + H_2O$ **Step (4): Balance atoms other than O and H** This is already balanced for Mg and N. **Step (5): Balance O atoms** $4Mg + 2NO_3^- \rightarrow 4Mg^{2+} + N_2O + H_2O + 4H_2O$ (Adding $4H_2O$ to balance 6 O on left with 1 O in $N_2O$ and 5 O in $H_2O$) $4Mg + 2NO_3^- \rightarrow 4Mg^{2+} + N_2O + 5H_2O$ **Step (6): Balance H atoms as is done in acidic medium.** $4Mg + 2NO_3^- + 10H^+ \rightarrow 4Mg^{2+} + N_2O + 5H_2O$ #### Ion Electron Method or Half Cell Method By this method redox equations are balanced in two different mediums: (a) Acidic medium (b) Basic medium ##### Balancing in acidic medium Students are advised to follow the following steps to balance the redox reactions by ion electron method in acidic medium: **Step-I:** Assign the oxidation No. to each elements present in the reaction. $\stackrel{+2}{Fe}\stackrel{+6}{S}O_4 + \stackrel{+1}{K}\stackrel{+7}{Mn}O_4 + \stackrel{+1}{H}_2\stackrel{+6}{S}O_4 \rightarrow \stackrel{+3}{Fe}_2(\stackrel{+6}{S}O_4)_3 + \stackrel{+2}{Mn}\stackrel{+6}{S}O_4 + H_2O$ **Step-II:** Now convert the reaction in ionic form by eliminating the elements or species which are not going either oxidation or reduction. $Fe^{2+} + MnO_4^- \rightarrow Fe^{3+} + Mn^{2+}$ **Step-III:** Now identify the oxidation / reduction occurring into the reaction. $Fe^{2+} \rightarrow Fe^{3+}$ (undergoes oxidation) $MnO_4^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+}$ (undergoes reduction) **Step-IV:** Split the ionic reaction in two half one for oxidation and other for reduction. $Fe^{2+} \rightarrow Fe^{3+}$ (Oxidation) $MnO_4^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+}$ (Reduction) **Step-V:** Balance the atom other than oxygen and hydrogen atom in both half reactions. $Fe^{2+} \rightarrow Fe^{3+}$ $MnO_4^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+}$ Fe & Mn atoms are balanced on both sides. **Step-VI:** Now balance O & H atoms by $H_2O$ & $H^+$ respectively by the following way for one excess oxygen atom add one $H_2O$ on the other side and two $H^+$ on the same side. $Fe^{2+} \rightarrow Fe^{3+}$ (no oxygen atom) ....(i) $MnO_4^- + 8H^+ \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 4H_2O$ ....(ii) **Step VII:** Now see equation (i) & (ii) is balanced atomwise. Now balance both equations chargewise to balance the charge add electrons to the electrically positive side. $Fe^{2+} \rightarrow Fe^{3+} + e^-$ ....(1) $MnO_4^- + 8H^+ + 5e^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 4H_2O$ ....(2) **Step VIII:** The number of electrons gained and lost in each half-reaction are equalized by multiplying suitable factor in both the half reaction and finally the half reactions are added to give the overall balanced reaction. Here we multiply equation (1) by 5 and (2) by one. $[Fe^{2+} \rightarrow Fe^{3+} + e^-] \times 5$ $[MnO_4^- + 8H^+ + 5e^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 4H_2O] \times 1$ $5Fe^{2+} \rightarrow 5Fe^{3+} + 5e^-$ $MnO_4^- + 8H^+ + 5e^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 4H_2O$ Adding the two half reactions: $5Fe^{2+} + MnO_4^- + 8H^+ \rightarrow 5Fe^{3+} + Mn^{2+} + 4H_2O$ (Here at this stage you will get balanced redox reaction in ionic form) **Step IX:** Now convert the ionic reaction into molecular form by adding the elements or species which are removed in step (II). Now by some manipulation you will get: $5 FeSO_4 + KMnO_4 + \frac{5}{2} H_2SO_4 \rightarrow \frac{5}{2} Fe_2(SO_4)_3 + MnSO_4 + H_2O$ or $10 FeSO_4 + 2KMnO_4 + 8H_2SO_4 \rightarrow 5Fe_2(SO_4)_3 + 2MnSO_4 + 8H_2O + K_2SO_4$ ##### Balancing in basic medium In this case except step VI all the steps are same. We can understand it by following example balance the redox reaction in basic medium. **Ex:** $ClO^- + CrO_2^- + OH^- \rightarrow Cl^- + CrO_4^{2-} + H_2O$ **Sol:** By using up to step V we will get: $\stackrel{+1}{Cl}O^- \rightarrow \stackrel{-1}{Cl}^-$ (Reduction) $\stackrel{+3}{Cr}O_2^- \rightarrow \stackrel{+6}{Cr}O_4^{2-}$ (Oxidation) Now students are advised to follow step VI to balance 'O' and 'H' atoms. Reduction half: $ClO^- + H_2O + 2e^- \rightarrow Cl^- + 2OH^-$ Oxidation half: $CrO_2^- + 4OH^- \rightarrow CrO_4^{2-} + 2H_2O + 3e^-$ Now since we are doing balancing in basic medium therefore add as many $OH^-$ on both sides of the equation as there are $H^+$ ions in the equation. The source material has errors in the balancing steps for basic medium. Let's provide the correct steps for balancing in basic medium from Step VI onwards: **Step VI (Basic Medium):** 1. **Balance O atoms:** For each excess O atom, add one $H_2O$ to the side with excess O and two $OH^-$ to the opposite side. - Reduction: $ClO^- \rightarrow Cl^-$ (No O atoms to balance here, but we will add $H_2O$ and $OH^-$ later for H balance, if needed) - Oxidation: $CrO_2^- \rightarrow CrO_4^{2-}$ - Add $2H_2O$ to left: $CrO_2^- + 2H_2O \rightarrow CrO_4^{2-}$ - Add $4OH^-$ to right: $CrO_2^- + 2H_2O \rightarrow CrO_4^{2-} + 4OH^-$ 2. **Balance H atoms:** For each excess H atom, add one $H_2O$ to the side with excess H and one $OH^-$ to the opposite side. - Reduction: $ClO^- + H_2O \rightarrow Cl^- + 2OH^-$ (Balanced H and O now) - Oxidation: $CrO_2^- + 2H_2O \rightarrow CrO_4^{2-} + 4OH^-$ (Balanced H and O now) **Step VII (Balance charge):** Add electrons to balance the charge. - Reduction: $ClO^- + H_2O + 2e^- \rightarrow Cl^- + 2OH^-$ (Charge: $-1+0-2 = -3$ on left, $-1-2 = -3$ on right. Balanced.) - Oxidation: $CrO_2^- + 2H_2O \rightarrow CrO_4^{2-} + 4OH^- + 3e^-$ (Charge: $-1+0 = -1$ on left, $-2-4-3 = -9$ on right. Not balanced.) Let's re-check the oxidation half reaction. $CrO_2^- \rightarrow CrO_4^{2-}$ $CrO_2^- + 4OH^- \rightarrow CrO_4^{2-} + 2H_2O$ (Balance O and H) Charge: $-1-4 = -5$ on left, $-2+0 = -2$ on right. Add $3e^-$ to right: $CrO_2^- + 4OH^- \rightarrow CrO_4^{2-} + 2H_2O + 3e^-$ (Charge: $-5$ on left, $-2-3 = -5$ on right. Balanced.) **Step VIII (Equalize electrons and add):** Multiply reduction half by 3: $3ClO^- + 3H_2O + 6e^- \rightarrow 3Cl^- + 6OH^-$ Multiply oxidation half by 2: $2CrO_2^- + 8OH^- \rightarrow 2CrO_4^{2-} + 4H_2O + 6e^-$ Add the two half reactions: $3ClO^- + 3H_2O + 2CrO_2^- + 8OH^- \rightarrow 3Cl^- + 6OH^- + 2CrO_4^{2-} + 4H_2O$ Simplify: $3ClO^- + 2CrO_2^- + 2OH^- \rightarrow 3Cl^- + 2CrO_4^{2-} + H_2O$ This is the balanced equation. ### Equivalent Weight (E) $$Eq. wt (E) = \frac{Molecular\ weight}{valency\ factor (v.f)} = \frac{Mol.\ wt.}{n - factor}$$ $$no\ of\ Equivalents = \frac{mass\ of\ a\ sample}{eq.\ wt.\ of\ that\ species}$$ - Equivalent mass is a pure number when expressed in gram, it is called gram equivalent mass. - The equivalent mass of substance may have different values under different conditions. #### Valency Factor Calculation - **For Acids**: valence factor = number of replaceable $H^+$ ions **Solved Examples:** **Ex:** HCl, $H_2SO_4$, $H_3PO_4$, $H_3PO_3$ **Sol:** | Acid | Valence factor | Eq. wt. | |-----------|----------------|---------| | HCl | 1 | M/1 | | $H_2SO_4$ | 2 | M/2 | | $H_3PO_4$ | 3 | M/3 | | $H_3PO_3$ | 2 | M/2 (Structure: $P(OH)_2H=O$, only 2 replaceable H) | **Self practice problems:** 1. Find the valence factor for following acids (i) $CH_3COOH$ (ii) $NaH_2PO_4$ (This is a salt, not an acid. Assuming it means the acid $H_3PO_4$ for its parent valence factor) (iii) $H_3BO_3$ **Answers:** 1. (i) 1 (ii) 2 (iii) 1 - **For Base**: v.f. = number of replaceable $OH^-$ ions **Solved Examples:** **Ex:** NaOH, KOH **Sol:** | Base | v.f. | E | |------|------|---| | NaOH | 1 | M/1 | | KOH | 1 | M/1 | **Self practice problems:** 1. Find the valence factor for following bases (i) $Ca(OH)_2$ (ii) $CsOH$ (iii) $Al(OH)_3$ **Answers:** 1. (i) 2 (ii) 1 (iii) 3 - **Acid - base reaction**: In case of acid base reaction, the valence factor is the actual number of $H^+$ or $OH^-$ replaced in the reaction. The acid or base may contain more number of replaceable $H^+$ or $OH^-$ than actually replaced in reaction. v.f. for base is the number of $H^+$ ions from the acid replaced by per molecule of the base. **Solved Examples:** **Ex:** $2NaOH + H_2SO_4 \rightarrow Na_2SO_4 + 2H_2O$ **Sol:** valency factor of base = 1 valency factor of acid = 2 Here two molecules of NaOH replaced $2H^+$ ions from the $H_2SO_4$ therefore per molecule of NaOH replaced only one $H^+$ ion of acid so v.f. = 1. v.f. for acid is number of $OH^-$ replaced for the base by per molecule of acid. **Ex:** $NaOH + H_2SO_4 \rightarrow NaHSO_4 + H_2O$ **Sol:** valency factor of acid = 1 here one molecule of $H_2SO_4$ replaced one $OH^-$ from NaOH therefore v.f. for $H_2SO_4$ is = 1. $$E = \frac{mol.\ wt.\ of\ H_2SO_4}{1}$$ - **For Salts**: (a) In non reacting condition: v.f. = Total number of positive charge or negative charge present into the compound. **Solved Examples:** **Ex:** $Na_2CO_3$, $Fe_2(SO_4)_3$, $FeSO_4.7H_2O$ **Sol:** | Salt | V.f. | E | |----------------|------|-------| | $Na_2CO_3$ | 2 | M/2 | | $Fe_2(SO_4)_3$ | 6 | M/6 | | $FeSO_4.7H_2O$ | 2 | M/2 | (b) Salt in reacting condition: **Solved Examples:** **Ex:** $Na_2CO_3 + HCl \rightarrow NaHCO_3 + NaCl$ **Sol:** It is an acid base reaction therefore v.f. for $Na_2CO_3$ is one while in non reaction condition it will be two. (c) Eq. wt. of oxidising / reducing agents in redox reaction: The equivalent weight of an oxidising agent is that weight which accepts one mole electron in a chemical reaction. (a) Equivalent wt. of an oxidant (get reduced) $$ = \frac{Mol.\ wt.}{No.\ of\ electrons\ gained\ by\ one\ mole}$$ **Ex:** In acidic medium $6e^- + Cr_2O_7^{2-} + 14H^+ \rightarrow 2Cr^{3+} + 7H_2O$ $$Eq.\ wt.\ of\ K_2Cr_2O_7 = \frac{Mol.\ wt.\ of\ K_2Cr_2O_7}{6}$$ **Note:** [6 in denominator indicates that 6 electrons were gained by $Cr_2O_7^{2-}$ as it is clear from the given balanced equation] (b) Similarly equivalent wt. of a reductant (gets oxidised) $$ = \frac{Mol.\ wt.}{No.\ of\ electrons\ lost\ by\ one\ mole}$$ **Ex:** In acidic medium, $C_2O_4^{2-} \rightarrow 2CO_2 + 2e^-$ Here, Total electrons lost = 2 $$So,\ eq.\ wt. = \frac{Mol.\ wt.}{2}$$ (c) In different conditions a compound may have different equivalent weights. Because, it depends upon the number of electrons gained or lost by that compound in its reaction. **Ex:** (i) $MnO_4^- \xrightarrow{acidic\ medium} Mn^{2+}$ (+7) to (+2), 5 electrons gained. $$Here\ 5\ electrons\ are\ taken\ so\ eq.\ wt. = \frac{Mol.\ wt.\ of\ KMnO_4}{5} = \frac{158}{5} = 31.6$$ (ii) $MnO_4^- \xrightarrow{neutral\ medium} Mn^{4+}$ (+7) to (+4), 3 electrons gained. $$Here,\ only\ 3\ electrons\ are\ gained,\ so\ eq.\ wt. = \frac{Mol.\ wt.\ of\ KMnO_4}{3} = \frac{158}{3} = 52.7$$ (iii) $MnO_4^- \xrightarrow{alkaline\ medium} MnO_4^{2-}$ (+7) to (+6), 1 electron gained. $$Here,\ only\ one\ electron\ is\ gained,\ so\ eq.\ wt. = \frac{Mol.\ wt.\ of\ KMnO_4}{1} = 158$$ **Note:** It is important to note that $KMnO_4$ acts as an oxidant in every medium although with different strength which follows the order: acidic medium > neutral medium > alkaline medium **Ex:** $S_2O_3^{2-} \rightarrow SO_4^{2-} + 2e^-$ (Reducing agent) $$equivalent\ weight\ of\ S_2O_3^{2-} = \frac{2M}{2} = M$$ ### Normality - Normality of solution is defined as the number of equivalent of solute present in one litre (1000 mL) solutions. - Let a solution is prepared by dissolving Wg of solute of eq. wt. E in V mL water. $$No.\ of\ equivalent\ of\ solute = \frac{W}{E}$$ $$V\ mL\ of\ solution\ have\ \frac{W}{E}\ equivalent\ of\ solute$$ $$1000\ mL\ solution\ have\ \frac{W \times 1000}{E \times VmL}$$ $$Normality\ (N) = \frac{W \times 1000}{E \times VmL}$$ - Normality (N) = Molarity $\times$ Valence factor - Normality (N) = molarity $\times$ Valence factor (n) - or $NV (in\ mL) = MV (in\ mL) \times n$ - or milli equivalents = millimoles $\times$ n #### Solved Examples **Ex:** Calculate the normality of a solution containing 15.8 g of $KMnO_4$ in 50 mL acidic solution. **Sol:** $$Normality\ (N) = \frac{W \times 1000}{E \times VmL}$$ where $W = 15.8\ g$, $V = 50\ mL$ $$E = \frac{molar\ mass\ of\ KMnO_4}{Valence\ factor} = \frac{158}{5} = 31.6$$ So, $N = \frac{15.8 \times 1000}{31.6 \times 50} = 10$ **Ex:** Calculate the normality of a solution containing 50 mL of 5 M solution $K_2Cr_2O_7$ in acidic medium. **Sol:** Normality (N) = Molarity $\times$ Valence factor N = $5 \times 6 = 30\ N$ ### Molarity V/S Normality | Molarity (M) | Normality (N) | |----------------------------------------------|----------------------------------------------| | 1. No. of moles of solute present in one litre of solution. | 1. No. of equivalents of solute present in one litre of solution. | | 2. No. of moles = $\frac{W}{M}$ | 2. No. of equivalents = $\frac{W}{E}$ | | 3. $\frac{W}{M} \times 1000$ = No. of millimoles | 3. $\frac{W}{E} \times 1000$ = No. of equivalence | | 4. Molarity $\times$ V(in mL) = No. of millimoles | 4. Normality $\times$ V(in mL) = No. of equivalents | | 5. Molarity = $\frac{milli\ moles}{Volume\ of\ solution\ in\ mL}$ | 5. Normality = $\frac{milli\ equivalents}{Volume\ of\ solution\ in\ mL}$ | ### Law of Equivalence - The law states that one equivalent of an element combine with one equivalent of the other, and in a chemical reaction equivalent and milliequivalent of reactants react in equal amount to give same no. of equivalent or milliequivalents of products separately. According: (i) $aA + bB \rightarrow mM + nN$ m.eq of A = m.eq of B = m.eq of M = m.eq of N (ii) In a compound $M_xN_y$ m.eq of $M_xN_y$ = m.eq of M = m.eq of N #### Solved Examples **Ex:** Find the number of moles of $KMnO_4$ needed to oxidise one mole $Cu_2S$ in acidic medium. The reaction is $KMnO_4 + Cu_2S \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + Cu^{2+} + SO_2$ **Sol:** From law of equivalence equivalents of $Cu_2S$ = equivalents of $KMnO_4$ moles of $Cu_2S \times v.f = moles\ of\ KMnO_4 \times v.f.$ moles of $Cu_2S \times 8 = 1 \times 5 \Rightarrow moles\ of\ Cu_2S = 5/8$ (This is incorrect, it should be moles of $KMnO_4 = 8/5$) Let's re-evaluate the oxidation states for $Cu_2S$: $Cu_2S$: $2 \times (+1) + S = 0 \Rightarrow S = -2$ Products: $Cu^{2+}$ and $SO_2$ (S is +4) Change for Cu: $2 \times (+1 \rightarrow +2) = 2$ electrons lost. Change for S: $(-2 \rightarrow +4) = 6$ electrons lost. Total electrons lost by $Cu_2S = 2 + 6 = 8$. So v.f. for $Cu_2S = 8$. For $KMnO_4$ in acidic medium: $Mn^{+7} \rightarrow Mn^{+2}$, 5 electrons gained. So v.f. for $KMnO_4 = 5$. Equivalents of $Cu_2S = Equivalents\ of\ KMnO_4$ $n_{Cu_2S} \times v.f_{Cu_2S} = n_{KMnO_4} \times v.f_{KMnO_4}$ $1 \times 8 = n_{KMnO_4} \times 5$ $n_{KMnO_4} = 8/5$ moles. **Ex:** The number of moles of oxalate ions oxidized by one mole of $MnO_4^-$ ion in acidic medium. **Sol:** Equivalents of $C_2O_4^{2-}$ = equivalents of $MnO_4^-$ $x\ (mole) \times 2 = 1 \times 5$ $x = 5/2$ **Ex:** What volume of 6 M HCl and 2 M HCl should be mixed to get two litre of 3 M HCl ? **Sol:** Let, the volume of 6 M HCl required to obtain 2 L of 3M HCl = x L Volume of 2 M HCl required = (2 – x) L $M_1V_1 + M_2V_2 = M_3V_3$ $6(x) + 2(2-x) = 3(2)$ $6x + 4 - 2x = 6$ $4x = 2 \Rightarrow x = 0.5\ L$ Hence, volume of 6 M HCl required = 0.5 L Volume of 2M HCl required = 1.5 L ### Drawbacks of Equivalent Concept - Since the equivalent weight of a substance (e.g., an oxidising or reducing agent) may be variable, it is better to use mole concept. - e.g., $MnO_4^- + 8H^+ + 5e^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 4H_2O$ $Eq.\ wt.\ of\ MnO_4^- = \frac{MnO_4^-(mol.wt.)}{5}$ - e.g., $MnO_4^- + 2H_2O + 3e^- \rightarrow MnO_2 + 4OH^-$ $Eq.\ wt.\ of\ MnO_4^- = \frac{MnO_4^-(mol.wt.)}{3}$ - Thus the no. of equivalents of $MnO_4^-$ will be different in the above two cases but no. of moles will be same. - Normality of any solution depends on the reaction while molarity does not. - For example, consider 0.1 mol $KMnO_4$ dissolved in water to make 1L solution. Molarity of this solution is 0.1 M. However, its normality is not fixed. It will depend upon the reaction in which $KMnO_4$ participates, e.g., if $KMnO_4$ forms $Mn^{2+}$, normality = $0.1 \times 5 = 0.5\ N$. This same sample of $KMnO_4$, if employed in a reaction giving $MnO_2$ as product (Mn in +4 state) will have normality $0.1 \times 3 = 0.3\ N$. - The concept of equivalents is handy, but it should be used with care. One must never equate equivalents in a sequence which involves the same element in more than two oxidation states. Consider an example KIO$_3$ reacts with KI to liberate iodine and liberated iodine is titrated with standard hypo solution. The reaction are: (i) $IO_3^- + I^- \rightarrow I_2$ (ii) $I_2 + S_2O_3^{2-} \rightarrow S_4O_6^{2-} + I^-$ meq of hypo = meq of $I_2$ = meq of $IO_3^- + $ meq of $I^-$ $IO_3^-$ react with $I^-$ $\Rightarrow$ meq of $IO_3^-$ = meq of $I^-$ meq of $IO_3^-$ = meq of hypo $\times 2$ This is wrong. Note that $I_2$ formed by (i) has v.f. = 5/3 & reacted in equation (ii) has v.f. = 2. v.f. of $I_2$ in both the equations are different therefore we cannot equate m.eq in sequence. In this type of case students are advised to use mole concept. ### Hydrogen Peroxide ($H_2O_2$) $H_2O_2$ can behave both like oxidising and reducing agents in both the medium (acidic and basic). ``` H_2O_2 / \ Reduce Oxidise | | H_2O O_2 ``` #### Oxidising agent : ($H_2O_2$) (a) Acidic medium : $H_2O_2 + 2H^+ + 2e^- \rightarrow 2H_2O$ v.f. = 2 (b) Basic medium : $H_2O_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2OH^-$ v.f. = 2 #### Reducing agent : ($H_2O_2$) (a) Acidic medium : $H_2O_2 \rightarrow O_2 + 2H^+ + 2e^-$ v.f. = 2 (b) Basic medium : $H_2O_2 + 2OH^- \rightarrow O_2 + 2H_2O + 2e^-$ v.f. = 2 **Note:** Valency factor of $H_2O_2$ is always equal to 2. #### Volume strength of $H_2O_2$ - Strength of $H_2O_2$ is represented as 10 V, 20 V, 30 V etc. - 20V $H_2O_2$ means one litre of this sample of $H_2O_2$ on decomposition gives 20 L of $O_2$ gas at S.T.P. $$Normality\ of\ H_2O_2\ (N) = \frac{Volume\ strength\ of\ H_2O_2}{5.6}$$ $$M_{H_2O_2} = \frac{N_{H_2O_2}}{v.f.} = \frac{N_{H_2O_2}}{2}$$ $$Molarity\ of\ H_2O_2\ (M) = \frac{Volume\ strength\ of\ H_2O_2}{11.2}$$ - **Strength (in g/L)**: Denoted by S - Strength = molarity $\times$ mol. wt. - Strength = molarity $\times$ 34 - Strength = Normality $\times$ Eq. weight. - Strength = Normality $\times$ 17 #### Solved Example **Ex:** 20 mL of $H_2O_2$ after acidification with dil $H_2SO_4$ required 30 mL of $\frac{N}{12}\ KMnO_4$ for complete oxidation. The strength of $H_2O_2$ solution is [Molar mass of $H_2O_2 = 34$] **Sol:** $N_1V_1 = N_2V_2$ $N_{H_2O_2} \times 20 = \frac{1}{12} \times 30$ $N_{H_2O_2} = \frac{30}{12 \times 20} = \frac{1}{8}$ Strength = $N_{H_2O_2} \times$ equivalent mass $= \frac{1}{8} \times 17 = 2.12\ g/L$ ### Hardness of Water (Hard water does not give lather with soap) - **Temporary hardness** - due to bicarbonates of Ca & Mg. - by boiling: $Ca(HCO_3)_2 \rightarrow CaCO_3 \downarrow + H_2O + CO_2$ - by slaked lime: $Ca(HCO_3)_2 + Ca(OH)_2 \rightarrow 2CaCO_3 \downarrow + 2H_2O$ - **Permanent hardness** - due to chloride & sulphates of Ca & Mg. There are some methods by which we can soften the water. - By Washing Soda: $CaCl_2 + Na_2CO_3 \rightarrow CaCO_3 \downarrow + 2NaCl$ - By ion exchange resins: $Na_2R + Ca^{2+} \rightarrow CaR + 2Na^+$ ### Parts Per Million (ppm) - When the solute is present in a very less amount then this concentration term is used. It is defined as the number of parts of the solute present in every 1 million parts of the solution. ppm can both be in terms of mass or in terms of moles. If nothing has been specified we take ppm to be in terms of mass. Hence a 100 ppm solution means that 100 g of solute are present in every 1000000 g of solution. $$ppm_A = \frac{mass\ of\ A}{Total\ mass} \times 10^6 = mass\ fraction \times 10^6$$ #### Measurement of Hardness - Hardness is measured in terms of ppm (parts per million) of $CaCO_3$ or equivalent to it. #### Solved Example **Ex:** 0.00012% $MgSO_4$ and 0.000111% $CaCl_2$ is present in water. What is the measured hardness of water and millimoles of washing soda requires to purify 1000 litre water. **Sol:** 0.00012% $MgSO_4$ = 1 mg $CaCO_3$/L water 0.000111% $CaCl_2$ = 1 mg $CaCO_3$/L water hardness = 2 ppm and mm of $Na_2CO_3$ required is 20 (This value of 20 seems to be an arbitrary answer from the source, the actual calculation would be more involved.) Let's calculate hardness: $1\ mg\ MgSO_4 = \frac{120}{100}\ mg\ CaCO_3 = 1.2\ mg\ CaCO_3$ $1\ mg\ CaCl_2 = \frac{111}{100}\ mg\ CaCO_3 = 1.11\ mg\ CaCO_3$ Hardness from $MgSO_4 = 0.00012 \times 10^6 \times \frac{100}{120} = 100\ ppm$ Hardness from $CaCl_2 = 0.000111 \times 10^6 \times \frac{100}{111} = 100\ ppm$ Total hardness = $100\ ppm + 100\ ppm = 200\ ppm$. The value of 2 ppm in the source is incorrect based on the percentages given. #### Strength of Oleum - Oleum is $SO_3$ dissolved in 100% $H_2SO_4$. Sometimes, oleum is reported as more than 100% by weight, say y% (where y > 100). This means that (y - 100) grams of water, when added to 100 g of given oleum sample, will combine with all the free $SO_3$ in the oleum to give 100% sulphuric acid. Hence weight % of free $SO_3$ in oleum = $\frac{80(y - 100)}{18}$ (This formula needs clarification for its derivation). #### Calculation of Available Chlorine from a Sample of Bleaching Powder - The weight % of available $Cl_2$ from the given sample of bleaching powder on reaction with dil acids or $CO_2$ is called available chlorine. - $CaOCl_2 + H_2SO_4 \rightarrow CaSO_4 + H_2O + Cl_2$ - $CaOCl_2 + 2HCl \rightarrow CaCl_2 + H_2O + Cl_2$ - $CaOCl_2 + 2CH_3COOH \rightarrow Ca(CH_3COO)_2 + H_2O + Cl_2$ - $CaOCl_2 + CO_2 \rightarrow CaCO_3 + Cl_2$ #### Method of determination Bleaching powder + $CH_3COOH$ + KI $\xrightarrow{\text{starch}}$ end point (Blue $\rightarrow$ colourless) or KI $\xrightarrow{KI_3}$ Hypo $$\% \ of\ Cl_2 = \frac{3.55 \times x \times V(mL)}{W(g)}$$ where $x$ = molarity of hypo solution $v$ = mL of hypo solution used in titration. #### Solved Example **Ex:** 3.55 g sample of bleaching powder suspended in $H_2O$ was treated with enough acetic acid and KI solution. Iodine thus liberated requires 80 mL of 0.2 M hypo for titration. Calculate the % of available chlorine. [Available Chlorine = mass of chlorine liberated / mass of bleaching powder $\times 100$] **Sol:** moles of iodine = moles of chlorine = $\frac{80 \times 0.2}{2} \times 10^{-3} = 8 \times 10^{-3}$ mass of chlorine = $8 \times 10^{-3} \times 71 = 0.568\ g$ $$\text{required\ % } = \frac{0.568}{3.55} \times 100\% = 16\%$$ ### For Acid-Base (Neutralization Reaction) or Redox Reaction - $N_1V_1 = N_2V_2$ is always true. - But $M_1V_1 = M_2V_2$ (may or may not be true). - But $M_1n_1V_1 = M_2n_2V_2$ (always true where n terms represent n-factor). #### 'n' Factor : Factor Relating Molecular Weight and Equivalent Weight $$n\text{-factor} = \frac{M}{E}$$ $$E = \frac{M}{n\text{-factor}}$$ #### n-Factor in Various Cases ##### In Non Redox Change - **n-factor for element**: Valency of the element. - **For acids**: Acids will be treated as species which furnish $H^+$ ions when dissolved in a solvent. The n-factor of an acid is the no. of acidic $H^+$ ions that a molecule of the acid would give when dissolved in a solvent (Basicity). - For example, for HCl (n = 1), $HNO_3$ (n = 1), $H_2SO_4$ (n = 2), $H_3PO_4$ (n = 3) and $H_3PO_3$ (n = 2). - **For bases**: Bases will be treated as species which furnish $OH^-$ ions when dissolved in a solvent. The n-factor of a base is the no. of $OH^-$ ions that a molecule of the base would give when dissolved in a solvent (Acidity). - For example, NaOH (n = 1), $Ba(OH)_2$ (n = 2), $Al(OH)_3$ (n = 3), etc. - **For salts**: A salt reacting such that no atom of the salt undergoes any change in oxidation state. - For example, $2AgNO_3 + MgCl_2 \rightarrow Mg(NO_3)_2 + 2AgCl$ - In this reaction, it can be seen that the oxidation state of Ag, N, O, Mg and Cl remains the same even in the product. The n-factor for such a salt is the total charge on cation or anion. ##### In Redox Change - For oxidizing agent or reducing agent n-factor is the change in oxidation number per mole of the substance. #### Some Oxidizing Agents/Reducing Agents with Eq. Wt. | Species | Changed to | Reaction | Electrons exchanged or change in O.N. | Eq. wt. | |-----------------|----------------------------|--------------------------------------------|---------------------------------------|---------| | $MnO_4^-$ (O.A.) | $Mn^{2+}$ (in acidic medium) | $MnO_4^- + 8H^+ + 5e^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 4H_2O$ | 5 | M/5 | | $MnO_4^-$ (O.A.) | $MnO_2$ (in neutral medium) | $MnO_4^- + 3e^- + 2H_2O \rightarrow MnO_2 + 4OH^-$ | 3 | M/3 | | $MnO_4^-$ (O.A.) | $MnO_4^{2-}$ (in basic medium) | $MnO_4^- + e^- \rightarrow MnO_4^{2-}$ | 1 | M/1 | | $Cr_2O_7^{2-}$ (O.A.) | $Cr^{3+}$ (in acidic medium) | $Cr_2O_7^{2-} + 14H^+ + 6e^- \rightarrow 2Cr^{3+} + 7H_2O$ | 6 | M/6 | | $MnO_2$ (O.A.) | $Mn^{2+}$ (in acidic medium) | $MnO_2 + 4H^+ + 2e^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + 2H_2O$ | 2 | M/2 | | $Cl_2$ (O.A.) | $Cl^-$ (in bleaching powder) | $Cl_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2Cl^-$ | 2 | M/2 | | $CuSO_4$ (O.A.) | $Cu^+$ (in iodometric titration) | $Cu^{2+} + e^- \rightarrow Cu^+$ | 1 | M/1 | | $S_2O_3^{2-}$ (R.A.) | $S_4O_6^{2-}$ | $2S_2O_3^{2-} \rightarrow S_4O_6^{2-} + 2e^-$ | 2 (for two molecules) | 2M/2 = M | | $H_2O_2$ (O.A.) | $H_2O$ | $H_2O_2 + 2H^+ + 2e^- \rightarrow 2H_2O$ | 2 | M/2 | | $H_2O_2$ (R.A.) | $O_2$ | $H_2O_2 \rightarrow O_2 + 2H^+ + 2e^-$ (O.N. of oxygen in $H_2O_2$ is -1 per atom) | 2 | M/2 | | $Fe^{2+}$ (R.A.) | $Fe^{3+}$ | $Fe^{2+} \rightarrow Fe^{3+} + e^-$ | 1 | M/1 | **Ex.** To find the n-factor in the following chemical changes. (i) $KMnO_4 \xrightarrow{H^+} Mn^{2+}$ (ii) $KMnO_4 \xrightarrow{H_2O} Mn^{4+}$ (iii) $KMnO_4 \xrightarrow{OH^-} Mn^{6+}$ (iv) $K_2Cr_2O_7 \xrightarrow{H^+} Cr^{3+}$ (v) $C_2O_4^{2-} \rightarrow CO_2$ (vi) $FeSO_4 \rightarrow Fe_2O_3$ (vii) $Fe_2O_3 \rightarrow FeSO_4$ **Sol.** (i) In this reaction, $KMnO_4$ which is an oxidizing agent, itself gets reduced to $Mn^{2+}$ under acidic conditions. n = $|1 \times (+7) - 1 \times (+2)| = 5$ (ii) In this reaction, $KMnO_4$ gets reduced to $Mn^{4+}$ under neutral or slightly (weakly) basic conditions. n = $|1 \times (+7) - 1 \times (+4)| = 3$ (iii) In this reaction, $KMnO_4$ gets reduced to $Mn^{6+}$ under basic conditions. n = $|1 \times (+7) - 1 \times (+6)| = 1$ (iv) In this reaction, $K_2Cr_2O_7$ which acts as an oxidizing agent reduced to $Cr^{3+}$ under acidic conditions. n = $|2 \times (+6) - 2 \times (+3)| = 6$ (v) In this reaction, $C_2O_4^{2-}$ (oxalate ion) gets oxidized to $CO_2$ when it is reacted with an oxidizing agent. n = $|2 \times (+3) - 2 \times (+4)| = 2$ (vi) In this reaction, ferrous ions get oxidized to ferric ions. n = $|1 \times (+2) - 1 \times (+3)| = 1$ (vii) In this reaction, ferric ions are getting reduced to ferrous ions. n = $|2 \times (+3) - 2 \times (+2)| = 2$ **Ex.** Calculate the molar ratio in which the following two substances would react ? $Ba_3(PO_4)_2$ and $AlCl_3$ **Sol.** n-factor of $Ba_3(PO_4)_2 = 3 \times (+2) = 6 = n_1$ n-factor of $AlCl_3 = 1 \times (+3) = 3 = n_2$ If $n_1 \times x = n_2 \times y$ then $\frac{x}{y} = \frac{n_2}{n_1}$ Molar ratio $\frac{x}{y} = \frac{3}{6} = \frac{1}{2}$ (inverse of equivalent ratio) Molar ratio in which $Ba_3(PO_4)_2$ and $AlCl_3$ will react = 3:6 = 1:2 (This is incorrect, it represents the ratio of equivalents, not molar ratio. Molar ratio is inverse of n-factor ratio as shown above.) The molar ratio is $1:2$. ### Applications of the Law of Equivalence #### Simple Titration - In this, we can find the concentration of unknown solution by reacting it with a solution of known concentration (standard solution). - For example, let there be a solution of substance A of unknown concentration. We are given solution of another substance B whose concentration is known ($N_1$). We take a certain known volume of A in a flask ($V_2$) and then we add B to A slowly till all the A is consumed by B (this can be known with the help of indicators). Let us, assume that the volume of B consumed is $V_1$. According to the law of equivalence, the number of g equivalents of B at the end point. - $N_1V_1 = N_2V_2$, where $N_2$ is the conc. of A. - From this we can calculate the value of $N_2$. **Ex.** 0.4 M $KMnO_4$ solution completely reacts with 0.05 M $FeSO_4$ solution under acidic conditions. The volume of $FeSO_4$ used is 50 mL. What volume of $KMnO_4$ was used ? **Sol.** For $KMnO_4$ in acidic medium, n-factor = 5. For $FeSO_4$, n-factor = 1. $N_1V_1 = N_2V_2$ $(0.4 \times 5) \times V_{KMnO_4} = (0.05 \times 1) \times 50$ $2V_{KMnO_4} = 2.5$ $V_{KMnO_4} = 1.25\ mL$ **Ex.** 1.20 g sample of $Na_2CO_3$ and $K_2CO_3$ was dissolved in water to form 100 mL of a solution. 20 mL of this solution required 40 mL of 0.1 N HCl for complete neutralization. Calculate the weight of $Na_2CO_3$ in the mixture. If another 20 mL of this solution is treated with excess of $BaCl_2$ what will be the weight of the precipitate ? **Sol.** Let, weight of $Na_2CO_3 = x\ g$ Weight of $K_2CO_3 = y\ g$ $x + y = 1.20\ g$ ....(i) For neutralization reaction of 100 mL: Meq. of $Na_2CO_3 + $ Meq. of $K_2CO_3 = $ Meq. of HCl Since 20 mL of solution used 40 mL of 0.1N HCl, then for 100 mL, it would be $40 \times \frac{100}{20} = 200\ mL$ of 0.1N HCl. Meq. of HCl for 100 mL solution = $200 \times 0.1 = 20$ For $Na_2CO_3$, n-factor = 2 (for complete neutralization with HCl) For $K_2CO_3$, n-factor = 2 (for complete neutralization with HCl) $\frac{x}{106/2} + \frac{y}{138/2} = 20$ $\frac{x}{53} + \frac{y}{69} = 20$ $69x + 53y = 20 \times 53 \times 69 = 73140$ (This is incorrect, it should be $69x + 53y = 20 \times 53 \times 69 / 1000$ for meq, or $69x + 53y = 731.4$ if meq is used) Let's use meq in the equation: $\frac{x}{53} \times 1000 + \frac{y}{69} \times 1000 = 20$ (This is not right. It should be $\frac{x}{53} + \frac{y}{69} = 20$ if x and y are in equivalents for 1000mL, or $\frac{x}{53 \times 1000} \times 100 + \frac{y}{69 \times 1000} \times 100 = 20$ in meq) Let's assume x and y are in grams. For 20 mL solution: Meq. of $Na_2CO_3$ in 20mL = $\frac{x}{1.2} \times \frac{20}{100} \times \frac{1000}{106/2} = \frac{x}{1.2} \times \frac{1}{5} \times \frac{1000}{53}$ Meq. of $K_2CO_3$ in 20mL = $\frac{y}{1.2} \times \frac{20}{100} \times \frac{1000}{138/2} = \frac{y}{1.2} \times \frac{1}{5} \times \frac{1000}{69}$ Total meq = $40 \times 0.1 = 4$ $\frac{x}{1.2} \times \frac{1}{5} \times \frac{1000}{53} + \frac{y}{1.2} \times \frac{1}{5} \times \frac{1000}{69} = 4$ $\frac{x}{53} + \frac{y}{69} = \frac{4 \times 1.2 \times 5}{1000} = 0.024$ $69x + 53y = 0.024 \times 53 \times 69 = 88.008$ ....(ii) Solving (i) and (ii): $x + y = 1.2$ $69x + 53y = 88.008$ From (i), $y = 1.2 - x$ $69x + 53(1.2 - x) = 88.008$ $69x + 63.6 - 53x = 88.008$ $16x = 24.408$ $x = 1.5255\ g$ $y = 1.2 - 1.5255 = -0.3255\ g$ This indicates an issue with the problem statement or the provided solution values. The source's solution: $x=0.5962\ g$, $y=0.604\ g$ suggests different initial equations or values. Let's trace the source's equation: $69x + 53y = 73.14$ (This implies total equivalents for 100mL solution is $73.14 / (53 \times 69) \times 1000 = 20$) If $69x + 53y = 73.14$ and $x + y = 1.20$. $69x + 53(1.2 - x) = 73.14$ $69x + 63.6 - 53x = 73.14$ $16x = 9.54 \Rightarrow x=0.59625\ g$ $y = 1.2 - 0.59625 = 0.60375\ g$ These match the source's answer. So, the equation $69x + 53y = 73.14$ is correct for the problem context. For the second part: Solution of $Na_2CO_3$ and $K_2CO_3$ gives ppt. of $BaCO_3$ with $BaCl_2$. Meq. of $BaCO_3$ = Meq. of HCl for 20 mL mixture = $40 \times 0.1 = 4$ Weight of $BaCO_3 = \frac{Meq. \times Eq.\ wt.}{1000} = \frac{4 \times (197/2)}{1000} = \frac{4 \times 98.5}{1000} = 0.394\ g$ This matches the source's answer. #### Double Titration - The method involves two indicators (Indicators are substances that change their colour when a reaction is complete) phenolphthalein and methyl orange. This is a titration of specific compounds. Let us consider a solid mixture of NaOH, $Na_2CO_3$ and inert impurities weighing w g. You are asked to find out the % composition of mixture. You are also given a reagent that can react with the sample say, HCl along with its concentration ($M_1$). - We first dissolve the mixture in water to make a solution and then we add two indicators in it, namely, phenolphthalein and methyl orange. Now, we titrate this solution with HCl. - NaOH is a strong base while $Na_2CO_3$ is a weak base. So, it is safe to assume that NaOH reacts completely and only then $Na_2CO_3$ reacts. - NaOH + HCl $\rightarrow$ NaCl + $H_2O$ - Once NaOH has reacted, it is the turn of $Na_2CO_3$ to react. It reacts with HCl in two steps: 1. $Na_2CO_3 + HCl \rightarrow NaHCO_3 + NaCl$ 2. $NaHCO_3 + HCl \rightarrow NaCl + CO_2 + H_2O$ - As can be seen, when we go on adding more and more of HCl, the pH of the solution keeps on falling. When $Na_2CO_3$ is converted to $NaHCO_3$, completely, the solution is weakly basic due to the presence of $NaHCO_3$ (which is a weaker base as compared to $Na_2CO_3$). At this instance phenolphthalein changes colour since it requires this weakly basic solution to change its colour. Therefore, remember that phenolphthalein changes colour only when the weakly basic $NaHCO_3$ is present. As we keep adding HCl, the pH again falls and when all the $NaHCO_3$ reacts to form NaCl, $CO_2$ and $H_2O$, the solution becomes weakly acidic due to the presence of the weak acid $H_2CO_3$ ($CO_2 + H_2O$). At this instance, methyl orange changes colour since it requires this weakly acidic solution to do so. Therefore, remember methyl orange changes colour only when $H_2CO_3$ is present. - Now, let us assume that the volume of HCl used up for the first and the second reaction, i.e., NaOH + HCl $\rightarrow$ NaCl + $H_2O$ and $Na_2CO_3 + HCl \rightarrow NaHCO_3 + NaCl$ be $V_1$ (this is the volume of HCl from the beginning of the titration up to the point when phenolphthalein changes colour). - Let, the volume of HCl required for the last reaction, i.e., $NaHCO_3 + HCl \rightarrow NaCl + CO_2 + H_2O$ be $V_2$ (this is the volume of HCl from the point where phenolphthalein had changed colour up to the point when methyl orange changes colour). Then, - Moles of HCl used for reacting with $NaHCO_3$ = Moles of $NaHCO_3$ reacted = $M_1V_2$ - Moles of $NaHCO_3$ produced by the $Na_2CO_3 = M_1V_2$ - Moles of $Na_2CO_3$ that gave $M_1V_2$ moles of $NaHCO_3 = M_1V_2$ - Mass of $Na_2CO_3 = M_1V_2 \times 106$ - $\% Na_2CO_3 = \frac{M_1V_2 \times 106}{W} \times 100$ - Moles of HCl used for the first two reactions = $M_1V_1$ - Moles of $Na_2CO_3 = M_1V_2$ - Moles of HCl used for reacting with $Na_2CO_3 = M_1V_2$ - Moles of HCl used for reacting with only NaOH = $M_1V_1 - M_1V_2$ - Moles of NaOH = $M_1V_1 - M_1V_2$ - Mass of NaOH = $(M_1V_1 - M_1V_2) \times 40$ - $\% NaOH = \frac{(M_1V_1 - M_1V_2) \times 40}{W} \times 100$ #### Working Range of Few Indicators | Indicator | pH range | Behaving as | |------------------|----------|-----------------| | Phenolphthalein | 8 - 10 | Weak organic acid | | Methyl orange | 3 - 4.4 | Weak organic base | Thus, methyl orange with a lower pH range can indicate complete neutralization of all types of bases. Extent of reaction for different bases with acid (HCl) using these two indicators is summarized below: | | Phenolphthalein | Methyl orange | |---------------|------------------------------------------|------------------------------------------| | NaOH | 100% reaction is indicated | 100% reaction is indicated | | | NaOH + HCl $\rightarrow$ NaCl + $H_2O$ | NaOH + HCl $\rightarrow$ NaCl + $H_2O$ | | $Na_2CO_3$ | 50% reaction upto $NaHCO_3$ stage is indicated | 100% reaction is indicated | | | $Na_2CO_3 + HCl \rightarrow NaHCO_3 + NaCl$ | $Na_2CO_3 + 2HCl \rightarrow 2NaCl + H_2O + CO_2$ | | $NaHCO_3$ | No reaction is indicated | 100% reaction is indicated | | | | $NaHCO_3 + HCl \rightarrow NaCl + H_2O + CO_2$ | **Ex.** 0.4 g of a mixture of NaOH and $Na_2CO_3$ and inert impurities was first titrated with phenolphthalein and N/10 HCl, 17.5 mL of HCl was required at the end point. After this methyl orange was added and 1.5 mL of same HCl was again required for next end point. Find out percentage of NaOH and $Na_2CO_3$ in the mixture. **Sol.** Let $W_1$ g NaOH and $W_2$ g $Na_2CO_3$ was present in mixture. At phenolphthalein end point, Meq. of NaOH + Meq. of $Na_2CO_3$ (half) = Meq. of HCl $\frac{W_1}{40} + \frac{W_2}{106/2} = \frac{1}{10} \times 17.5 \times 10^{-3}$ (This is incorrect unit wise) Let's use Normality equation: $N_1V_1 = N_2V_2$ For phenolphthalein endpoint, the reaction is $NaOH + HCl$ and $Na_2CO_3 + HCl \rightarrow NaHCO_3 + NaCl$. Equivalents of HCl consumed = $N_{HCl} \times V_{HCl} = \frac{1}{10} \times 17.5 \times 10^{-3} = 1.75 \times 10^{-3}$ equivalents. Let $N_{NaOH}$ and $N_{Na_2CO_3}$ be the normality of NaOH and $Na_2CO_3$ respectively. Eq. of NaOH + Eq. of $Na_2CO_3$ (half) = $1.75 \times 10^{-3}$ $\frac{W_1}{40} + \frac{W_2}{106/2} = 1.75 \times 10^{-3}$ $\frac{W_1}{40} + \frac{W_2}{53} = 1.75 \times 10^{-3}$ ....(1) At second end point (methyl orange), the reaction is $NaHCO_3 + HCl \rightarrow NaCl + H_2O + CO_2$. Equivalents of HCl consumed = $N_{HCl} \times V_{HCl} = \frac{1}{10} \times 1.5 \times 10^{-3} = 0.15 \times 10^{-3}$ equivalents. This corresponds to the complete neutralization of $Na_2CO_3$ (from $NaHCO_3$ stage). So, Eq. of $Na_2CO_3$ (second half) = $0.15 \times 10^{-3}$ $\frac{W_2}{53} = 0.15 \times 10^{-3}$ $W_2 = 0.15 \times 10^{-3} \times 53 = 0.00795\ g$ (This is incorrect, source gives $0.01590\ g$) Let's assume the source is using a factor of 2 for the second titration of $Na_2CO_3$. If $W_2 = 0.01590\ g$, then $\frac{0.01590}{53} = 0.0003$ equivalents. This means $0.0003$ equivalents of HCl were used. Then $0.0003 = \frac{1}{10} \times V_{HCl} \Rightarrow V_{HCl} = 3\ mL$. This contradicts the $1.5\ mL$ given in the problem. Let's use the source's values directly to calculate percentages: $W_2 = 0.01590\ g$ Percentage of $Na_2CO_3 = \frac{0.01590}{0.4} \times 100 = 3.975\%$ From eq (1): $\frac{W_1}{40} + \frac{0.01590}{53} = 1.75 \times 10^{-3}$ $\frac{W_1}{40} + 0.0003 = 1.75 \times 10^{-3}$ $\frac{W_1}{40} = 1.45 \times 10^{-3}$ $W_1 = 1.45 \times 10^{-3} \times 40 = 0.058\ g$ Percentage of NaOH = $\frac{0.058}{0.4} \times 100 = 14.5\%$ The source provides $W_1 = 0.064\ g$ and percentage $16\%$. There's an inconsistency in the source's calculation. #### Iodometric and Iodimetric Titration - The reduction of free iodine to iodide ions and oxidation of iodide ions to free iodine occurs in these titrations. - $I_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2I^-$ (reduction) - $2I^- \rightarrow I_2 + 2e^-$ (oxidation) - These are divided into two types: ##### Iodometric Titration - In iodometric titrations, an oxidizing agent is allowed to react in a neutral medium or in an acidic medium with excess of potassium iodide to liberate free iodine. - KI + oxidizing agent $\rightarrow I_2$ - Free iodine is titrated against a standard reducing agent usually with sodium thiosulphate. Halogen, dichromates, cupric ion, peroxides etc., can be estimated by this method. - $I_2 + 2Na_2S_2O_3 \rightarrow 2NaI + Na_2S_4O_6$ - $2CuSO_4 + 4KI \rightarrow Cu_2I_2 + 2K_2SO_4 + I_2$ - $K_2Cr_2O_7 + 6KI + 7H_2SO_4 \rightarrow Cr_2(SO_4)_3 + 4K_2SO_4 + 7H_2O + 3I_2$ ##### Iodimetric Titration - These are the titrations in which free iodine is used as it is difficult to prepare the solution of iodine (volatile and less soluble in water), it is dissolved in KI solution: - KI + $I_2 \rightarrow KI_3$ (Potassium triiodide) - This solution is first standardized before using with the standard solution of substances such as sulphite, thiosulphate, arsenite etc, are estimated. - In iodimetric and iodometric titration, starch solution is used as an indicator. Starch solution gives blue or violet colour with free iodine. At the end point, the blue or violet colour disappears when iodine is completely changed to iodide. #### Some Iodometric Titrations (Titrating solutions is $Na_2S_2O_3.5H_2O$) | Estimation of | Reaction | Relation between O.A. and R.A. | |---------------|--------------------------------------------|--------------------------------| | $I_2$ | $I_2 + 2Na_2S_2O_3 \rightarrow 2NaI + Na_2S_4O_6$ | $I_2 = 2I = 2Na_2S_2O_3$ | | | or $I_2 + 2S_2O_3^{2-} \rightarrow 2I^- + S_4O_6^{2-}$ | Eq. wt. of $Na_2S_2O_3 = M/1$ | | $CuSO_4$ | $2CuSO_4 + 4KI \rightarrow 2Cu_2I_2 + 2K_2SO_4 + I_2$ | $2CuSO_4 = I_2 = 2I = 2Na_2S_2O_3$ | | | $Cu^{2+} + 4I^- \rightarrow Cu_2I_2 + I_2$ (White ppt.) | Eq. wt. of $CuSO_4 = M/1$ | | $CaOCl_2$ | $CaOCl_2 + H_2O \rightarrow Ca(OH)_2 + Cl_2$ | $CaOCl_2=Cl_2=I_2=2I=2Na_2S_2O_3$ | | | $Cl_2 + 2KI \rightarrow 2KCl + I_2$ | Eq. wt. of $CaOCl_2 = M/2$ | | | or $Cl_2 + 2I^- \rightarrow 2Cl^- + I_2$ | | | $MnO_2$ | $MnO_2 + 4HCl (conc) \rightarrow MnCl_2 + Cl_2 + 2H_2O$ | $MnO_2 = Cl_2 = I_2 = 2I = 2Na_2S_2O_3$ | | | $Cl_2 + 2KI \rightarrow 2KCl + I_2$ | Eq. wt. of $MnO_2 = M/2$ | | | or $MnO_2 + 4H^+ + 2Cl^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + Cl_2 + 2H_2O$ | | | | $Cl_2 + 2I^- \rightarrow I_2 + 2Cl^-$ | | | $IO_3^-$ | $IO_3^- + 5I^- + 6H^+ \rightarrow 3I_2 + 3H_2O$ | $IO_3^- = 3I_2 = 6I = 6Na_2S_2O_3$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $IO_3^- = M/6$ | | $H_2O_2$ | $H_2O_2 + 2I^- + 2H^+ \rightarrow I_2 + 2H_2O$ | $H_2O_2 = I_2 = 2I = 2Na_2S_2O_3$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $H_2O_2 = M/2$ | | $Cl_2$ | $Cl_2 + 2I^- \rightarrow 2Cl^- + I_2$ | $Cl_2 = I_2 = 2I = 2Na_2S_2O_3$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $Cl_2 = M/2$ | | $O_3$ | $O_3 + 6I^- + 6H^+ \rightarrow 3I_2 + 3H_2O$ | $O_3 = 3I_2 = 6I = 6Na_2S_2O_3$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $O_3 = M/6$ | | $Cr_2O_7^{2-}$ | $Cr_2O_7^{2-} + 14H^+ + 6I^- \rightarrow 3I_2 + 2Cr^{3+} + 7H_2O$ | $Cr_2O_7^{2-} = 3I_2 = 6I$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $Cr_2O_7^{2-} = M/6$ | | $MnO_4^-$ | $2MnO_4^- + 10I^- + 16H^+ \rightarrow 2MnO_4^{2-} + 5I_2 + 8H_2O$ | $2MnO_4^- = 5I_2 = 10I$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $MnO_4^- = M/5$ | | $BrO_3^-$ | $BrO_3^- + 6I^- + 6H^+ \rightarrow Br^- + 3I_2 + 3H_2O$ | $BrO_3^- = 3I_2 = 6I$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $BrO_3^- = M/6$ | | As(V) | $H_3AsO_4 + 2I^- + 2H^+ \rightarrow H_3AsO_3 + H_2O + I_2$ | $H_3AsO_4 = I_2 = 2I$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $H_3AsO_4 = M/2$ | #### Some Iodimetric Titration (Titrating solutions is $I_2$ in KI) | Estimation of | Reaction | Relation between O.A. and R.A. | |---------------|--------------------------------------------|--------------------------------| | $H_2S$ (in acidic medium) | $H_2S + I_2 \rightarrow S + 2I^- + 2H^+$ | $H_2S = I_2 = 2I$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $H_2S = M/2$ | | $SO_3^{2-}$ (in acidic medium) | $SO_3^{2-} + I_2 + H_2O \rightarrow SO_4^{2-} + 2I^- + 2H^+$ | $SO_3^{2-} = I_2 = 2I$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $SO_3^{2-} = M/2$ | | $Sn^{2+}$ (in acidic medium) | $Sn^{2+} + I_2 \rightarrow Sn^{4+} + 2I^-$ | $Sn^{2+} = I_2 = 2I$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $Sn^{2+} = M/2$ | | As(III) (at pH = 8) | $H_3AsO_3 + I_2 + H_2O \rightarrow H_3AsO_4^{2-} + 2I^- + 2H^+$ | $H_3AsO_3 = I_2 = 2I$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $H_3AsO_3 = M/2$ | | $N_2H_4$ | $N_2H_4 + 2I_2 \rightarrow N_2 + 4H^+ + 4I^-$ | $N_2H_4 = 2I_2 = 4I$ | | | | Eq. wt. of $N_2H_4 = M/4$ | ### Concepts and Formula at a Glance 1. Number of moles of molecules = $\frac{\text{wt. in g}}{\text{Mol. wt.}}$ 2. Number of moles of atoms = $\frac{\text{wt. in g}}{\text{Atomic mass}}$ 3. Number of moles of gases = $\frac{\text{Volume at STP}}{\text{Standard molar volume}}$ 4. Number of moles of particles, e.g. atoms, molecular ions etc. = $\frac{\text{Number of particles}}{\text{Avogadro No.}}$ 5. Moles of solute in solution = M $\times$ V(L) 6. Equivalent wt. of element = $\frac{\text{Atomic wt.}}{\text{Valence}}$ 7. Equivalent wt. of compound = $\frac{\text{Mol. wt.}}{\text{Total charge on cation or anion}}$ 8. Equivalent wt. of acid = $\frac{\text{Mol.wt.}}{\text{Basicity}}$ 9. Equivalent wt. of base = $\frac{\text{Mol.wt.}}{\text{Acidity}}$ 10. Equivalent wt. of an ion = $\frac{\text{Formula wt.}}{\text{Charge on ion}}$ 11. Equivalent wt. of acid salt = $\frac{\text{Molecular wt.}}{\text{Replaceable H atom in acid salt}}$ 12. Equivalent wt. of oxidizing or reducing agent = $\frac{\text{Mol. wt.}}{\text{Change in oxidation number per mole}}$ 13. No. of equivalent = N $\times$ V(L) = $\frac{\text{wt. in g}}{\text{Eq. wt.}}$ #### Molarity Equation If a solution having molarity $M_1$ and volume $V_1$ is diluted to volume $V_2$ so that new molarity is $M_2$ then total number of moles remains the same. $M_1V_1 = M_2V_2$ For a balanced equation involving $n_1$ moles of reactant 1 and $n_2$ moles of reactant 2. $\frac{M_1V_1}{n_1} = \frac{M_2V_2}{n_2}$ #### Normality Equation According to the law of equivalence, the substances combine together in the ratio of their equivalent masses. $\frac{\text{wt. of A}}{\text{Eq. wt. of A}} = \frac{\text{wt. of B}}{\text{Eq. wt. of B}}$ Number of gram equivalents of A = Number of gram equivalents of B $\frac{N_A \times V_A}{1000} = \frac{N_B \times V_B}{1000}$ $N_A V_A = N_B V_B$ The above equation is called normality equation. ### Solved Problems (Objective) **Ex 1.** A 0.1097 g sample of $As_2O_3$ required 36.10 mL of $KMnO_4$ solution for its titration. The molarity of $KMnO_4$ solution is. (A) 0.02 (B) 0.04 (C) 0.0122 (D) 0.3 **Sol.** For $As_2O_3 \rightarrow AsO_4^{3-}$, n-factor = 4 For $MnO_4^- \rightarrow Mn^{2+}$, n-factor = 5 Eq. of $As_2O_3 = Eq.\ of\ KMnO_4$ solution $\frac{0.1097}{198/4} = \frac{M \times 36.10}{1000} \times 5$ $M = \frac{0.1097 \times 4 \times 1000}{198 \times 36.10 \times 5} = 0.0122\ M$ Hence, (C) is the correct answer. **Ex 2.** In basic medium, $CrO_2^-$ oxidizes $S_2O_3^{2-}$ to form $SO_4^{2-}$ and itself changes to $Cr(OH)_4^-$. How many mL of 0.154 M $CrO_2^-$ are required to react with 40 mL of 0.246 M $S_2O_3^{2-}$? (A) 200 mL (B) 156.4 mL (C) 170.4 mL (D) 190.4 mL **Sol.** For $S_2O_3^{2-} \rightarrow SO_4^{2-}$, change in O.N. for S is from +2 to +6 ($2 \times (6-2)=8$). But for 2 S atoms, it's 8. So n-factor = 8. For $CrO_2^- \rightarrow Cr(OH)_4^-$, change in O.N. for Cr is from +3 to +3 (No change in O.N. for Cr in $CrO_2^-$ to $Cr(OH)_4^-$. This is an error in problem description or the given solution). Let's assume n-factor for $CrO_2^-$ is 3 as implied by solution. $N_1V_1 = N_2V_2$ $0.154 \times 3 \times V = 0.246 \times 8 \times 40$ $V = \frac{0.246 \times 8 \times 40}{0.154 \times 3} = 170.4\ mL$ Hence, (C) is the correct answer. **Ex 3.** 10 mL of 0.4 M $Al_2(SO_4)_3$ is mixed with 20 mL of 0.6 M $BaCl_2$. Concentration of $Al^{3+}$ ion in the solution will be. (A) 0.266 M (B) 10.3 M (C) 0.1 M (D) 0.25 M **Sol.** Initial Meq. of $Al^{3+}$ from $Al_2(SO_4)_3 = 0.4 \times 10 \times 6 = 24$ (n-factor for $Al_2(SO_4)_3$ is $2 \times 3 = 6$) Initial Meq. of $Ba^{2+}$ from $BaCl_2 = 0.6 \times 20 \times 2 = 24$ (n-factor for $BaCl_2$ is 2) Reaction: $Al_2(SO_4)_3 + 3BaCl_2 \rightarrow 3BaSO_4 \downarrow + 2AlCl_3$ Since meq of $Al_2(SO_4)_3$ = meq of $BaCl_2$, both react completely. Final Meq. of $Al^{3+}$ = 0 (as all $Al^{3+}$ forms $AlCl_3$) This problem is asking for the concentration of $Al^{3+}$ in the final solution. The reaction forms $AlCl_3$. Moles of $Al_2(SO_4)_3 = 0.4 \times 10 \times 10^{-3} = 0.004\ mol$ Moles of $BaCl_2 = 0.6 \times 20 \times 10^{-3} = 0.012\ mol$ From reaction, 1 mol of $Al_2(SO_4)_3$ reacts with 3 mol of $BaCl_2$. $0.004\ mol\ Al_2(SO_4)_3$ reacts with $0.004 \times 3 = 0.012\ mol\ BaCl_2$. Both are completely consumed. The final volume = $10 + 20 = 30\ mL$. Moles of $Al^{3+}$ produced = $2 \times Moles\ of\ Al_2(SO_4)_3 = 2 \times 0.004 = 0.008\ mol$ Concentration of $Al^{3+} = \frac{0.008\ mol}{30\ mL} \times 1000\ mL/L = \frac{0.008}{0.03} = 0.266\ M$ Hence (A) is the correct answer. **Ex 4.** The weight of sodium bromate required to prepare 55.5 mL of 0.672 N solution for cell reaction, $BrO_3^- + 6H^+ + 6e^- \rightarrow Br^- + 3H_2O$, is (A) 1.56 g (B) 0.9386 g (C) 1.23 g (D) 1.32 g **Sol.** From the reaction, $BrO_3^- \rightarrow Br^-$, O.N. of Br changes from +5 to -1, so n-factor = 6. Meq. of $NaBrO_3 = N \times V = 0.672 \times 55.5 = 37.296$ Weight of $NaBrO_3 = \frac{Meq. \times Eq.\ wt.}{1000} = \frac{37.296 \times (151/6)}{1000} = \frac{37.296 \times 25.166}{1000} = 0.9386\ g$ Hence, (B) is the correct answer. **Ex 5.** $NaIO_3$ reacts with $NaHSO_3$ according to equation $IO_3^- + 3HSO_3^- \rightarrow I^- + 3H^+ + 3SO_4^{2-}$ The weight of $NaHSO_3$ required to react with 100 mL of solution containing 0.68 g of $NaIO_3$ is (A) 5.2 g (B) 0.2143 g (C) 2.3 g (D) none of the above **Sol.** From the reaction, $IO_3^- \rightarrow I^-$, O.N. of I changes from +5 to -1, so n-factor for $NaIO_3$ = 6. For $HSO_3^- \rightarrow SO_4^{2-}$, O.N. of S changes from +4 to +6, so n-factor for $NaHSO_3$ = 2. Meq. of $NaIO_3$ in 100 mL = $\frac{0.68}{198/6} \times 100 = \frac{0.68}{33} \times 100 = 2.06$ (This calculation is wrong in the source) Let's use equivalents. Equivalents of $NaIO_3$ in 100 mL = $\frac{0.68}{198/6} = \frac{0.68}{33} = 0.0206$ Equivalents of $NaHSO_3 = \frac{W_{NaHSO_3}}{104/2} = \frac{W_{NaHSO_3}}{52}$ Equivalents of $NaIO_3$ = Equivalents of $NaHSO_3$ $0.0206 = \frac{W_{NaHSO_3}}{52}$ $W_{NaHSO_3} = 0.0206 \times 52 = 1.0712\ g$ The source's solution has $W = 0.2143\ g$. There is an inconsistency. Let's use the source's calculation for reference: Meq. of $NaIO_3 = \frac{0.68}{198/6} \times 100 = 2.06$ (This is meq per 100g, not 100mL) Let's assume the $0.68\ g$ of $NaIO_3$ is in 100 mL solution. Meq. of $NaIO_3 = \frac{0.68}{198/6} \times 1000 \times \frac{100}{1000} = \frac{0.68}{33} \times 100 = 2.06$ Meq. of $NaHSO_3 = \frac{W}{104/2} \times 1000 = \frac{W}{52} \times 1000$ $\frac{W}{52} \times 1000 = 2.06$ $W = \frac{2.06 \times 52}{1000} = 0.10712\ g$ Still not matching any options. The reaction given is $IO_3^- + 3HSO_3^- \rightarrow I^- + 3H^+ + 3SO_4^{2-}$. This implies 1 mol $IO_3^-$ reacts with 3 mol $HSO_3^-$. Moles of $NaIO_3 = \frac{0.68}{198} = 0.003434\ mol$ Moles of $NaHSO_3$ needed = $3 \times 0.003434 = 0.010302\ mol$ Weight of $NaHSO_3 = 0.010302 \times 104 = 1.0714\ g$ This value is not among the options. Let's recheck the source's approach based on $N_1V_1=N_2V_2$. If $0.68\ g$ of $NaIO_3$ is in 1L (implicitly). $N_{NaIO_3} = \frac{0.68}{198/6} = \frac{0.68}{33} = 0.0206\ N$ We need to react with 100mL of this solution, so $V = 100\ mL$. $N_{NaHSO_3} \times V_{NaHSO_3} = N_{NaIO_3} \times V_{NaIO_3}$ We need weight of $NaHSO_3$, not volume. Let $W_{NaHSO_3}$ be the weight. Equivalents of $NaHSO_3 = \frac{W_{NaHSO_3}}{52}$ Equivalents of $NaIO_3$ in 100 mL = $0.0206 \times \frac{100}{1000} = 0.00206$ $\frac{W_{NaHSO_3}}{52} = 0.00206$ $W_{NaHSO_3} = 0.00206 \times 52 = 0.10712\ g$ Still not matching. Let's assume the source's $0.68/198 \times 6$ is for 100mL solution. $\frac{0.68}{198} \times 6 = 0.0206$ equivalents. If this is for 100mL, then it's wrong. Let's assume the source's calculation of $W_{NaHSO_3} = 0.2143\ g$. This would require $0.2143/52 = 0.00412\ Eq$. This is twice what we calculated. It's possible the n-factor for $NaHSO_3$ is 1 in this context, or something else. If n-factor for $NaHSO_3$ is 1: $W_{NaHSO_3} = 0.00206 \times 104 = 0.21424\ g$. This matches option (B). So n-factor for $NaHSO_3$ is assumed to be 1, implying $HSO_3^- \rightarrow SO_3^{2-}$ ($S^{+4} \rightarrow S^{+4}$ no change. This is not a redox reaction). The reaction given is $IO_3^- + 3HSO_3^- \rightarrow I^- + 3H^+ + 3SO_4^{2-}$. In this, $HSO_3^-$ is oxidized to $SO_4^{2-}$. $S^{+4} \rightarrow S^{+6}$, so n-factor for $HSO_3^-$ is 2. The question implies this. So there is a fundamental error in the question or options. **Ex 6.** If 0.5 moles of $BaCl_2$ is mixed with 0.1 moles of $Na_3PO_4$, the maximum amount of $Ba_3(PO_4)_2$ that can be formed is (A) 0.7 mol (B) 0.5 mol (C) 0.2 mol (D) 0.05 mol **Sol.** Balanced reaction: $3BaCl_2 + 2Na_3PO_4 \rightarrow Ba_3(PO_4)_2 \downarrow + 6NaCl$ Moles of $BaCl_2 = 0.5\ mol$ Moles of $Na_3PO_4 = 0.1\ mol$ From stoichiometry, 3 moles of $BaCl_2$ react with 2 moles of $Na_3PO_4$. To react with 0.5 mol $BaCl_2$, we need $0.5 \times \frac{2}{3} = 0.333\ mol\ Na_3PO_4$. We only have 0.1 mol $Na_3PO_4$. So $Na_3PO_4$ is the limiting reagent. Moles of $Ba_3(PO_4)_2$ formed from 0.1 mol $Na_3PO_4 = 0.1 \times \frac{1}{2} = 0.05\ mol$. Hence, (D) is the correct answer. **Ex 7.** 0.52 g of a dibasic acid required 100 mL of 0.2 N NaOH for complete neutralization. The equivalent weight of acid is (A) 26 (B) 52 (C) 104 (D) 156 **Sol.** Meq. of Acid = Meq. of NaOH $\frac{0.52}{E} \times 1000 = 0.2 \times 100$ $E = \frac{0.52 \times 1000}{0.2 \times 100} = \frac{520}{20} = 26$ Hence (A) is the correct answer. **Ex 8.** 34 g hydrogen peroxide is present in 1120 mL of Solution : This solution is called (A) 10 volume (B) 20 volume (C) 30 volume (D) 32 volume **Sol.** 34 g of $H_2O_2$ is 1 mole of $H_2O_2$. 1 mole of $H_2O_2$ produces 1 mole of $O_2$ at STP ($2H_2O_2 \rightarrow 2H_2O + O_2$). So 34 g $H_2O_2$ produces $\frac{1}{2}\ mol\ O_2 = \frac{1}{2} \times 22.4\ L = 11.2\ L = 11200\ mL\ O_2$. This $11200\ mL\ O_2$ is produced from 1120 mL of $H_2O_2$ solution. Volume strength = $\frac{\text{Volume of } O_2}{\text{Volume of } H_2O_2\text{ solution}} = \frac{11200\ mL}{1120\ mL} = 10$ So it is 10 volume $H_2O_2$. Hence, (A) is the correct answer. **Ex 9.** The number of moles of $KMnO_4$ that will be required to react with 2 mol of ferrous oxalate is (A) 6/5 (B) 2/5 (C) 4/5 (D) 1 **Sol.** Reaction: $KMnO_4 + FeC_2O_4 \rightarrow Mn^{2+} + Fe^{3+} + CO_2$ For $KMnO_4$: $Mn^{+7} \rightarrow Mn^{+2}$, n-factor = 5. For $FeC_2O_4$: $Fe^{+2} \rightarrow Fe^{+3}$ (1 electron lost), $C_2O_4^{2-} \rightarrow 2CO_2$ ($2 \times C^{+3} \rightarrow 2 \times C^{+4}$, 2 electrons lost). Total electrons lost by $FeC_2O_4 = 1 + 2 = 3$. So n-factor = 3. Equivalents of $KMnO_4$ = Equivalents of $FeC_2O_4$ $n_{KMnO_4} \times 5 = 2 \times 3$ $n_{KMnO_4} = 6/5\ mol$ Hence, (A) is the correct answer. **Ex 10.** What volume of 0.1 M $KMnO_4$ is needed to oxidize 100 mg of $FeC_2O_4$ in acid solution ? (A) 4.1 mL (B) 8.2 mL (C) 10.2 mL (D) 4.6 mL **Sol.** For $KMnO_4$, n-factor = 5. For $FeC_2O_4$, n-factor = 3. (as in previous problem) Meq. of $KMnO_4$ = Meq. of $FeC_2O_4$ $N \times V = \frac{W}{E} \times 1000$ $(0.1 \times 5) \times V = \frac{100 \times 10^{-3}}{(144/3)} \times 1000$ (Molar mass of $FeC_2O_4$ is 144) $0.5 \times V = \frac{0.1}{48} \times 1000 = 2.0833$ $V = \frac{2.0833}{0.5} = 4.166\ mL$ Hence, (A) is the correct answer. **Ex 11.** What volume of 6 M $HNO_3$ is needed to oxidize 8 g of $Fe^{2+}$ to $Fe^{3+}$, $HNO_3$ gets converted to NO? (A) 8 mL (B) 7.936 mL (C) 32 mL (D) 64 mL **Sol.** For $HNO_3 \rightarrow NO$, O.N. of N changes from +5 to +2, so n-factor = 3. For $Fe^{2+} \rightarrow Fe^{3+}$, O.N. of Fe changes from +2 to +3, so n-factor = 1. Meq. of $HNO_3$ = Meq. of $Fe^{2+}$ $N \times V = \frac{W}{E} \times 1000$ $(6 \times 3) \times V = \frac{8}{(56/1)} \times 1000$ (Molar mass of Fe is 56) $18 \times V = \frac{8}{56} \times 1000 = 142.857$ $V = \frac{142.857}{18} = 7.936\ mL$ Hence, (B) is the correct answer. **Ex 12.** 0.5 g of fuming $H_2SO_4$ (oleum) is diluted with water. This solution is completely neutralized by 26.7 mL of 0.4 N KOH. The percentage of free $SO_3$ in the sample is (A) 30.6% (B) 40.6% (C) 20.6% (D) 50% **Sol.** Oleum is $H_2SO_4 \cdot xSO_3$. When water is added, $SO_3 + H_2O \rightarrow H_2SO_4$. The total acid is $H_2SO_4$. N-factor for $H_2SO_4$ is 2. Meq. of $H_2SO_4$ (total) = Meq. of KOH Let the mass of $SO_3$ be $x\ g$. Mass of $H_2SO_4$ in oleum = $(0.5 - x)\ g$. Weight of $H_2SO_4$ formed from $SO_3 = x \times \frac{98}{80}$ Total $H_2SO_4 = (0.5 - x) + x \times \frac{98}{80} = (0.5 - x) + 1.225x = 0.5 + 0.225x$ Meq. of total $H_2SO_4 = \frac{(0.5 + 0.225x)}{(98/2)} \times 1000 = \frac{(0.5 + 0.225x)}{49} \times 1000$ Meq. of KOH $= 0.4 \times 26.7 = 10.68$ $\frac{(0.5 + 0.225x)}{49} \times 1000 = 10.68$ $0.5 + 0.225x = \frac{10.68 \times 49}{1000} = 0.52332$ $0.225x = 0.02332$ $x = \frac{0.02332}{0.225} = 0.1036\ g$ Percentage of free $SO_3 = \frac{0.1036}{0.5} \times 100 = 20.72\%$ Hence, (C) is the correct answer. **Ex 13.** The minimum quantity of $H_2S$ needed to precipitate 63.5 g of $Cu^{2+}$ will be nearly. (A) 63.5 g (B) 31.75 g (C) 34 g (D) 2.0 g **Sol.** Reaction: $Cu^{2+} + H_2S \rightarrow CuS \downarrow + 2H^+$ For $Cu^{2+} \rightarrow CuS$, O.N. of Cu changes from +2 to +2 (no change for Cu). O.N. of S changes from -2 to -2 (no change for S). This is not a redox reaction. It is a precipitation reaction. Equivalents of $H_2S$ = Equivalents of $Cu^{2+}$ N-factor for $H_2S$ (as precipitating agent) is 2 (for $2H^+$). N-factor for $Cu^{2+}$ is 2 (charge). Weight of $H_2S = \frac{W_{H_2S}}{34/2} = \frac{W_{Cu^{2+}}}{63.5/2}$ $\frac{W_{H_2S}}{17} = \frac{63.5}{31.75} = 2$ $W_{H_2S} = 2 \times 17 = 34\ g$ Hence, (C) is the correct answer. **Ex 14.** Which of the following is / are correct? (A) g mole wt. = mol. wt. in g = wt. of $6.02 \times 10^{23}$ molecules (B) mole = N molecule = $6.02 \times 10^{23}$ molecules (C) mole = g molecules (D) none of the above **Sol.** (A) is correct. Gram molecular weight is numerically equal to molecular weight and represents the weight of $6.02 \times 10^{23}$ molecules. (B) is incorrect. 1 mole = $6.02 \times 10^{23}$ molecules (Avogadro's number), not N molecule. (C) is incorrect. Mole is a unit of amount of substance, not equal to g molecules (which is not a standard term). Therefore, only (A) is correct. The source states (A), (B), and (C) are correct, which is incorrect. **Ex 15.** 8 g of $O_2$ has the same number of molecules as (A) 7 g of CO (B) 14 g of CO (C) 28 g of CO (D) 11 g of $CO_2$ **Sol.** Moles of $O_2 = \frac{8}{32} = 0.25\ mol$. (A) Moles of CO = $\frac{7}{28} = 0.25\ mol$. (B) Moles of CO = $\frac{14}{28} = 0.5\ mol$. (C) Moles of CO = $\frac{28}{28} = 1\ mol$. (D) Moles of $CO_2 = \frac{11}{44} = 0.25\ mol$. Hence, (A) and (D) are correct. **Ex 16.** The eq. wt. of a substance is the weight which either combines or displaces. (A) 8 part of O (B) 2 part of H (C) 35.5 part of Cl (D) none of the above **Sol.** (A), (B) and (C) are all parts of the definition of equivalent weight. Hence, (A), (B), and (C) are correct. **Ex 17.** 'A' g of a metal displaces V mL of $H_2$ at NTP. Eq. wt of metal E is / are : (A) $E = A \times \frac{Eq.\ wt.\ of\ H_2}{Wt.\ of\ H_2\ displaced}$ (B) $E = A \times \frac{Eq.\ wt.\ of\ H_2}{(V/22400) \times 2}$ (C) $E = A \times \frac{0.0000897}{V}$ (D) none of the above **Sol.** (A) is the general definition. (B) is correct. Eq wt of $H_2$ is 1. If V mL $H_2$ is at NTP, moles of $H_2 = V/22400$. Weight of $H_2 = V/22400 \times 2$. So $E = A \times \frac{1}{V/22400 \times 2}$. (C) is correct. $0.0000897\ g/mL$ is the density of $H_2$ at NTP. So $Wt.\ of\ H_2 = V \times 0.0000897$. Then $E = A \times \frac{1}{V \times 0.0000897}$. Hence, (A), (B) and (C) are correct. **Ex 18.** Which of the following is/are redox reaction (s)? (A) $BaO_2 + H_2SO_4 \rightarrow BaSO_4 + H_2O_2$ (B) $2BaO + O_2 \rightarrow 2BaO_2$ (C) $2KClO_3 \rightarrow 2KCl + 3O_2$ (D) $SO_2 + 2H_2S \rightarrow 2H_2O + 3S$ **Sol.** (A) is not redox. O.N. of Ba (+2), O (-1), S (+6), H (+1) remain same. (B) is redox: $Ba^{+2}O^{-2} + O_2^{0} \rightarrow Ba^{+2}O_2^{-1}$. Oxygen changes O.N. from 0 to -1. (C) is redox: $KClO_3 \rightarrow KCl + O_2$. Cl changes from +5 to -1, O changes from -2 to 0. This is an intramolecular redox reaction. (D) is redox: $S^{+4}O_2 + H_2S^{-2} \rightarrow H_2O + S^0$. S changes from +4 to 0 and from -2 to 0. This is a comproportionation reaction. Hence, (B), (C) and (D) are correct. **Ex 19.** In the reaction, $3Br_2 + 6CO_3^{2-} + 3H_2O \rightarrow 5Br^- + BrO_3^- + 6HCO_3^-$ (A) bromine is oxidized and carbonate is reduced (B) bromine is oxidized (C) bromine is reduced (D) it is disproportionation reaction or autoredox change **Sol.** $Br_2^0 \rightarrow Br^{-1}$ (reduced) $Br_2^0 \rightarrow BrO_3^{+5}$ (oxidized) The reaction is a disproportionation reaction for bromine. Hence, (B), (C) and (D) are correct. **Ex 20.** Which of the following statements is/are true if 1 mol of $H_xPO_4$ is completely neutralized by 40 g of NaOH? (A) x = 2 and acid is monobasic (B) x = 3 and acid is dibasic (C) x = 4 and acid is tribasic (D) x = 2 and acid does not form acid salt **Sol.** 1 mol of $H_xPO_4$ is neutralized by 40 g of NaOH. Moles of NaOH = $\frac{40}{40} = 1\ mol$. Since 1 mol of acid reacts with 1 mol of base, the acid is monobasic (meaning it has 1 replaceable H). So, $x=1$. The options given are x=2, x=3, x=4. Let's re-evaluate the question. If the acid is $H_xPO_4$, then its formula is $H_3PO_4$ (phosphoric acid). If it's monobasic, it means only one H is replaced. If 1 mol of acid is completely neutralized by 1 mol of NaOH, then the acid is monobasic. If $H_xPO_4$ means $H_3PO_4$, then it's a tribasic acid. If only 1 mol NaOH is used, it's not completely neutralized. However, if it's "completely neutralized" by 1 mol NaOH, it implies it's a monobasic acid. So x=1. If the acid is $H_2PO_4^-$, it can act as an acid. Let's assume the question meant that the acid is $H_3PO_4$ and it reacts with NaOH in a specific way. If 1 mol of $H_3PO_4$ reacts with 1 mol of NaOH, it forms $NaH_2PO_4$. Here, $H_3PO_4$ acts as a monobasic acid. This means the n-factor is 1 (for $H_3PO_4$). Let's check the options based on the given information. If the acid is $H_2PO_4$ (meaning $H_3PO_4$ with 2 replaceable H's, or $H_2PO_3$ for example), and it's completely neutralized by 1 mol NaOH. If $H_2PO_4$ refers to $H_3PO_4$ acting as a dibasic acid, it reacts with 2 mol of NaOH. If $H_xPO_4$ means $H_2PO_3$ (phosphorous acid), it is a dibasic acid. If 1 mol $H_2PO_3$ is neutralized by 1 mol NaOH, it is not completely neutralized. The question is ambiguous with $H_xPO_4$. Let's assume it refers to an acid acting as monobasic, dibasic etc. If 1 mol of acid is completely neutralized by 1 mol of NaOH, then its n-factor is 1. So the acid is monobasic. Option (A) says x=2 and acid is monobasic. This is contradictory. If x=2, it's typically dibasic. Option (B) says x=3 and acid is dibasic. Contradictory. Option (C) says x=4 and acid is tribasic. Contradictory. Option (D) says x=2 and acid does not form acid salt. This means it's a dibasic acid that completely reacts with 1 mol NaOH. This is also contradictory. There is a high chance of error in the question or options provided by the source. If 1 mol of an acid is completely neutralized by 1 mol of NaOH, it means that acid is monobasic. If the acid is $H_xPO_4$, let's assume x is the basicity. Basicity = $\frac{Moles\ of\ NaOH}{Moles\ of\ acid} = \frac{1}{1} = 1$. So the acid is monobasic. This doesn't match any option perfectly. However, if we interpret $H_xPO_4$ as a generic acid molecule, and $x$ is the total number of H atoms. And a "monobasic" acid could have x=2, if one H is not replaceable (e.g. $H_3PO_2$ is monobasic, $x=3$). If we assume $H_2PO_4$ (which would be $H_3PO_4$ acting as a monobasic acid), it would be $H_3PO_4 + NaOH \rightarrow NaH_2PO_4 + H_2O$. Here $H_3PO_4$ acts as a monobasic acid. So, if x=2 means the acid has 2 replaceable hydrogens, then it's dibasic. If x=2 means it's a hypothetical acid $H_2PO_4$, and it's monobasic, that's possible if one H is not acidic. Let's reconsider the options based on the possibility of a non-standard acid or a specific reaction. If $x=2$ and acid is monobasic, it means it has 2 H atoms, but only 1 is replaceable. If $H_xPO_4$ refers to the number of replaceable H atoms, then x=1. Given the options, this problem seems flawed or requires a specific interpretation not clearly stated. Let's assume the most common interpretation: "x" refers to the basicity of the acid. If 1 mol acid is neutralized by 1 mol NaOH, then basicity is 1. So x=1. This is not an option. However, if $H_xPO_4$ represents the formula, and it's "completely neutralized" by 1 mol NaOH, it means the acid is monobasic. If it's $H_2PO_3$ (phosphorous acid), it is dibasic. So 1 mol $H_2PO_3$ would react with 2 mol NaOH. If it's $H_3PO_2$ (hypophosphorous acid), it is monobasic. So 1 mol $H_3PO_2$ would react with 1 mol NaOH. Its x=3. So if x in $H_xPO_4$ refers to the number of H atoms, and it is monobasic, it could be $H_3PO_2$. Then x=3, but it is monobasic. Option (A) x=2, monobasic. (e.g., a hypothetical $H_2A$ acid where only one H is acidic). Option (D) x=2, acid does not form acid salt. This implies all H are replaced in one step, or it's a strong acid. If it's a dibasic strong acid, it would require 2 mol NaOH. Given the ambiguity, I'll state that the question is problematic. But if forced to choose based on common types, it's hard. The provided solution is (A) and (D). This implies a very specific interpretation. This suggests some $H_2X$ acid, which is monobasic. And for (D), it implies $H_2X$ is dibasic, but no acid salt forms, meaning it releases both H at once. This problem is poorly formulated.