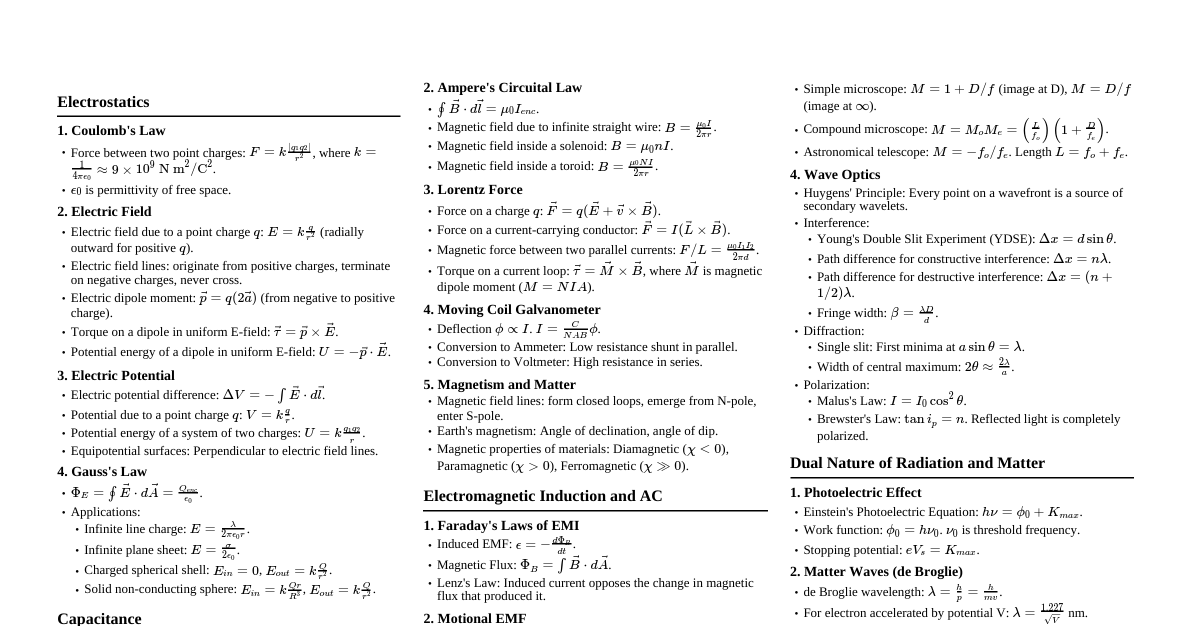

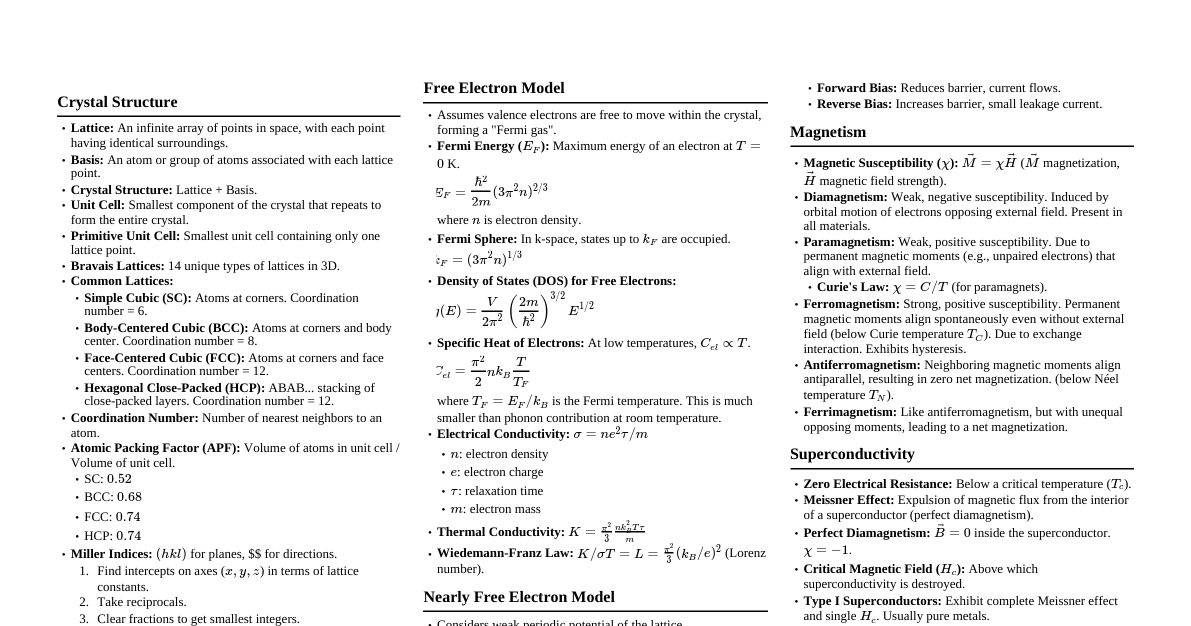

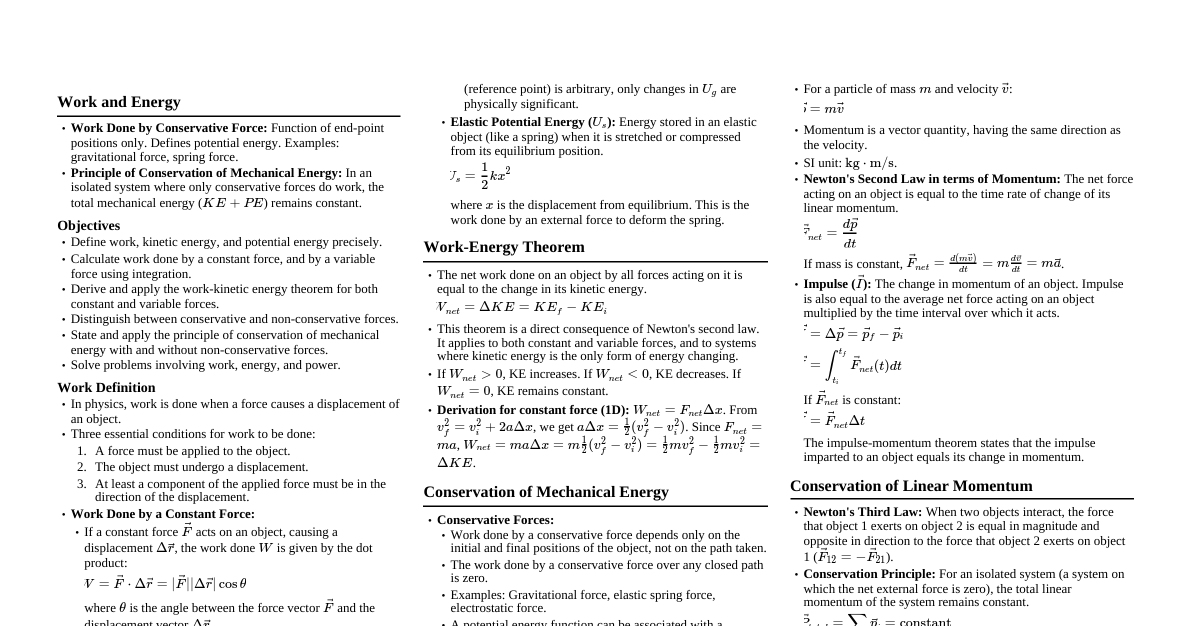

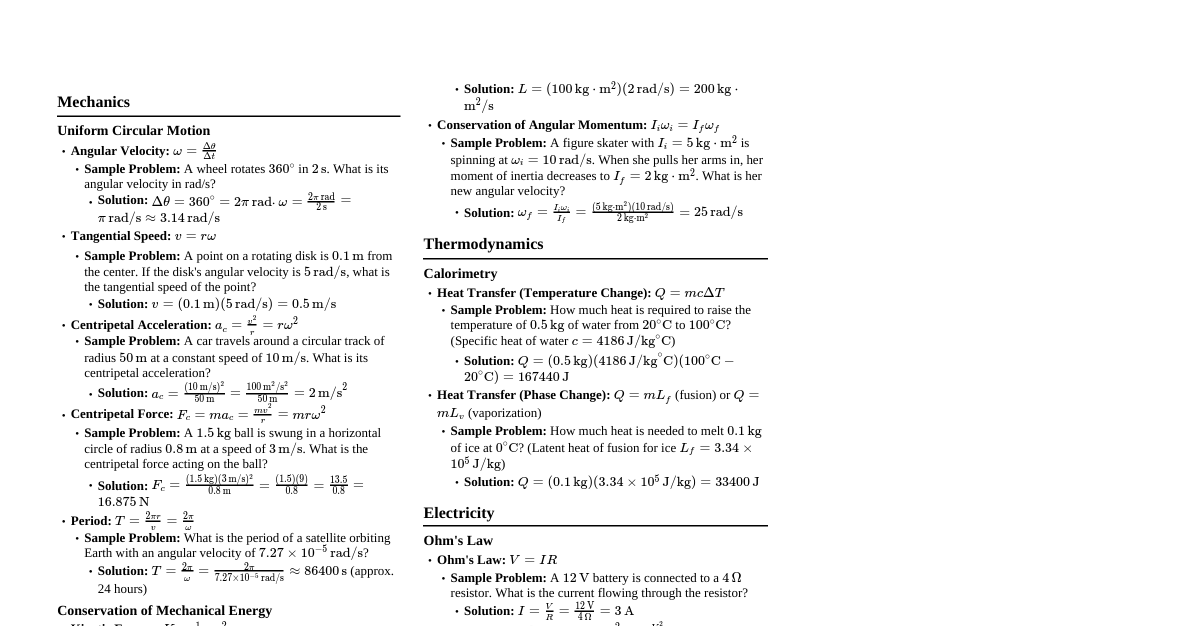

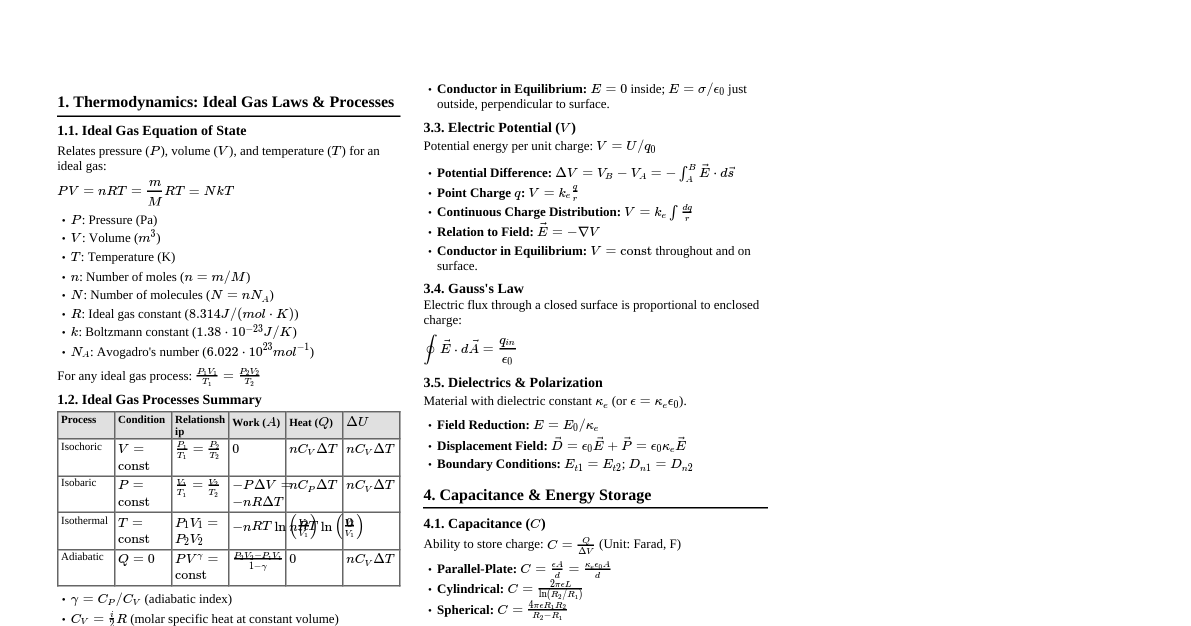

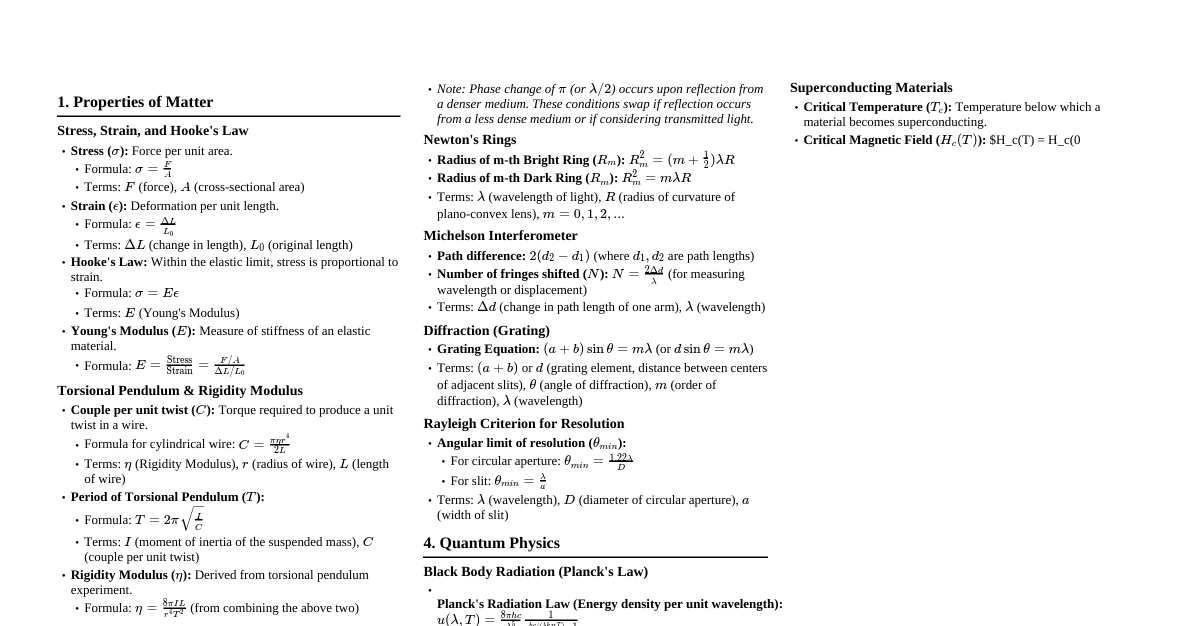

Physics For Engineers (25PH1000) Class Day Time 1 Tuesday 10:00-10:50 AM 2 Thursday 11:00-11:50 AM 3 Friday 8:00-8:50 AM 4 Friday (Lab) 3:00-4:50 PM @L-117 L T P C 3 0 2 4 Course Contents Vectors: Unit vectors in Cartesian, spherical, and cylindrical polar co-ordinates; Transformation of coordinate systems, line, surface, and volume integrals, Concept of scalar and vector fields; Gradient of a scalar field; Directional derivative, Equipotential surfaces, Conservative vector fields and their potential functions-gravitational and electrostatic examples. Flux: Divergence of a vector, Gauss's theorem, Continuity equation; Curl-rotational and irrational vector fields, Stoke's theorem. Conservation principles for matter, energy, and electrical charge, physical applications in gravitation and electrostatics. Irrotational versus rotational vector fields Electrostatics: Electrostatic potential and field due to discrete and continuous charge distributions, boundary condition, Energy for a charge distribution, Conductors and capacitors, Laplace's equation Image problem, Dielectric polarization, electric displacement vector, dielectric susceptibility, energy in dielectric systems Magnetostatics: Lorentz Force law - Biot-Savart's law and Ampere's law in magnetostatics, Divergence and curl of B, Magnetic induction due to configurations of current-carrying conductors, Magnetization and bound currents, Energy density in a magnetic field, Magnetic permeability and susceptibility, Boundary conditions Electrostatics Introduction Electrostatics means electric charges at rest (no moving charges). Objects become charged by gaining or losing electrons by two kinds of charges: Positive: Shortage of Electrons Negative: Excess of Electrons Neutrons can't be transferred! Forces between charges: Same charges repel each other. Opposite charges attract each other. Charging Objects Rub (Friction): Electrons are transferred if two objects are rubbed against each other. Conduction (Touching): Electrons are transferred if a charged object touches a neutral object. Polarization (Induction): Charged particles in a neutral object rearrange if a charged object is brought close to it (Causes temporary charge distribution). Conservation of Charge: Charge cannot be created or destroyed, but only transferred from one object to another. Electric Field The fundamental problem in electrodynamics expects to solve in this study. Source charge: A charge to produce electric field, generating electric fields. It may be a point charge or a continuous distribution of charges. Test charge: A small electro positive charge used for experiments that does not disturb any field. The electric field is a vector quantity that varies from point to point and is determined by the configuration of source charges. Coulomb's Law The force $\vec{F}$ between two point charges $q$ and $Q$ separated by a distance $r$ is given by: $F = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \frac{qQ}{r^2} \hat{r}$ The constant $\epsilon_0$ is the permittivity of free space : $\epsilon_0 = 8.85 \times 10^{-12} \text{ C}^2 \text{ N}^{-1} \text{ m}^{-2}$. The force is proportional to the product of the charges and inversely proportional to the square of the separation distance. It is repulsive if $q$ and $Q$ have the same sign, and attractive if their signs are opposite. The closer two charges are, the stronger the force between them. Superposition Principle The interaction between any two charges is completely unaffected by the presence of others. The total force on a charge $Q$ due to multiple source charges $q_1, q_2, \ldots, q_n$ is the vector sum of individual forces: $F = F_1 + F_2 + F_3 + \ldots$ The electric field $\vec{E}$ due to multiple source charges is: $E(\vec{r}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{q_i}{r_i^2} \hat{r}_i$ Continuous Charge Distribution For continuous charge distributions, the summation becomes an integral: Line charge density $\lambda$: $dq = \lambda dl'$ $E(\vec{r}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \int \frac{\lambda(\vec{r}')}{r^2} \hat{r} dl'$ Surface charge density $\sigma$: $dq = \sigma da'$ $E(\vec{r}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \int \frac{\sigma(\vec{r}')}{r^2} \hat{r} da'$ Volume charge density $\rho$: $dq = \rho d\tau'$ $E(\vec{r}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \int \frac{\rho(\vec{r}')}{r^2} \hat{r} d\tau'$ Field Lines and Flux Field Lines: Show the direction of the electric field. Density of lines indicates the magnitude of the field (strong near center, weak far apart). They always point radially outward from positive charges and inward to negative charges. Electric Flux ($\Phi_E$): The measure of the "number of field lines" passing through a surface $S$. $\Phi_E = \int_S \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{a}$ If electric field is uniform: $\Phi_E = E \cdot S \cos\theta$ If electric field is non-uniform: $\Phi_E = \int_S \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{a}$ Gauss's Law Gauss's law states that the total electric flux passing through any closed surface is equal to the enclosed charge $Q_{enc}$ divided by the permittivity of free space $\epsilon_0$: $\Phi_E = \oint_S \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{a} = \frac{Q_{enc}}{\epsilon_0}$ If field lines are leaving the enclosed surface, electric flux is positive. If field lines are entering the enclosed surface, electric flux is negative. A charge outside the surface doesn't contribute to the total flux. Gauss's law is always true, but its application is greatly simplified by symmetry: Spherical symmetry: Use a concentric sphere as the Gaussian surface. Cylindrical symmetry: Use a coaxial cylinder. Plane symmetry: Use a Gaussian "pillbox" straddling the surface. Gauss's Law in Differential Form Applying the divergence theorem to Gauss's Law yields: $\int_V (\nabla \cdot \vec{E}) d\tau = \int_V \frac{\rho}{\epsilon_0} d\tau$ Since this holds for any volume, the integrands must be equal: $\nabla \cdot \vec{E} = \frac{\rho}{\epsilon_0}$ Electric Potential The amount of work/energy needed to move an electric charge from a reference point to a specific point in an electric field. The line integral of $\vec{E}$ around any closed loop is zero ($\oint \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{l} = 0$). The line integral of $\vec{E}$ from point $a$ to point $b$ is independent of the path. We can define a scalar function $V(\vec{r})$, called the electric potential , such that: $V(\vec{r}) = -\int_{\mathcal{O}}^{\vec{r}} \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{l}$ The potential difference between $a$ and $b$ is $V(b) - V(a) = -\int_a^b \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{l}$. Equipotential: A surface over which the potential is constant. Superposition Principle: The potential at any given point is the sum of the potentials due to all the source charges separately. Potential has units Nm/C or J/C (Joules per Coulomb), which is a Volt . Potential from Charge Distributions Point Charge $q$: $V(\vec{r}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \frac{q}{r}$ Collection of charges: $V(\vec{r}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{q_i}{r_i}$ Continuous volume charge: $V(\vec{r}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \int \frac{\rho(\vec{r}')}{r} d\tau'$ Continuous line charge: $V(\vec{r}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \int \frac{\lambda(\vec{r}')}{r} dl'$ Continuous surface charge: $V(\vec{r}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \int \frac{\sigma(\vec{r}')}{r} da'$ Gradient of an Electrostatic Potential If you know $V$, you can easily get $\vec{E}$ by taking the gradient: $\vec{E} = -\nabla V$ In rectangular coordinates: $\vec{E} = - \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial x} \hat{a}_x + \frac{\partial V}{\partial y} \hat{a}_y + \frac{\partial V}{\partial z} \hat{a}_z \right)$ In cylindrical coordinates: $\vec{E} = - \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial \rho} \hat{a}_\rho + \frac{1}{\rho} \frac{\partial V}{\partial \phi} \hat{a}_\phi + \frac{\partial V}{\partial z} \hat{a}_z \right)$ In spherical coordinates: $\vec{E} = - \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial r} \hat{a}_r + \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial V}{\partial \theta} \hat{a}_\theta + \frac{1}{r \sin\theta} \frac{\partial V}{\partial \phi} \hat{a}_\phi \right)$ Boundary Conditions The electric field $\vec{E}$ always undergoes a discontinuity when crossing a surface charge $\sigma$. The normal component of $\vec{E}$ is discontinuous by an amount $\sigma/\epsilon_0$ at any boundary: $E_{\text{above}}^\perp - E_{\text{below}}^\perp = \frac{\sigma}{\epsilon_0} \hat{n}$ The tangential component of $\vec{E}$ is always continuous: $E_{\text{above}}^{\parallel} - E_{\text{below}}^{\parallel} = 0$ The potential $V$ is continuous across any boundary: $V_{\text{above}} = V_{\text{below}}$ The gradient of $V$ inherits the discontinuity in $\vec{E}$: $\nabla V_{\text{above}} - \nabla V_{\text{below}} = -\frac{\sigma}{\epsilon_0} \hat{n}$ The normal derivative of $V$ is discontinuous across the surface: $\frac{\partial V_{\text{above}}}{\partial n} - \frac{\partial V_{\text{below}}}{\partial n} = -\frac{\sigma}{\epsilon_0}$ Energy for a Charge Distribution Energy of a Point Charge Distribution The work $W$ required to assemble a collection of point charges is: $W = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{n} q_i V(\vec{r}_i)$ where $V(\vec{r}_i)$ is the potential at point $\vec{r}_i$ due to all other charges. Alternatively, $W = \frac{1}{8\pi\epsilon_0} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j \neq i}^{n} \frac{q_i q_j}{r_{ij}}$ Energy of a Continuous Charge Distribution For a volume charge density $\rho$: $W = \frac{1}{2} \int_V \rho V d\tau$ In terms of the electric field $\vec{E}$: $W = \frac{\epsilon_0}{2} \int_V E^2 d\tau$ Conductors Definition: Materials with free charges (e.g., metals) where electrons can move freely. $\vec{E} = 0$ inside a conductor: Any field inside causes charges to move, neutralizing the field until electrostatics conditions are met. $\rho = 0$ inside a conductor: If $\vec{E}=0$, then $\nabla \cdot \vec{E} = \rho/\epsilon_0 = 0$. Conductors are equipotentials: $V$ is constant throughout a conductor. $\vec{E}$ is perpendicular to the surface: Just outside a conductor, charge cannot flow along the surface. Net charge resides on the surface: Any excess charge will distribute itself on the surface. Induced Charges Bringing a charge near an uncharged conductor attracts opposite charges and repels like charges. If there's a hollow cavity in a conductor, and charge inside, the field in the cavity is not zero. External fields are canceled at the outer surface by induced charges. Surface Charge and Force on a Conductor The field immediately outside a conductor is $\vec{E} = \frac{\sigma}{\epsilon_0} \hat{n}$. The force per unit area on the surface of a conductor is $f = \sigma \vec{E}_{\text{average}} = \frac{1}{2} \sigma (\vec{E}_{\text{above}} + \vec{E}_{\text{below}})$. The electrostatic pressure on the surface is $P = \frac{\epsilon_0}{2} E^2$. Capacitors Definition: Two conductors separated by a dielectric, storing charge. Capacitance ($C$): The constant of proportionality between charge $Q$ and potential difference $V$. $C = \frac{Q}{V}$ Units are Farads (F = C/V). Microfarads ($\mu$F) and picofarads (pF) are common. Energy stored ($W$): The work done to charge a capacitor. $W = \frac{1}{2} C V^2 = \frac{1}{2} \frac{Q^2}{C} = \frac{1}{2} Q V$ Parallel-Plate Capacitor For two metal surfaces of area $A$ separated by distance $d$: $C = \frac{\epsilon_0 A}{d}$ Coaxial Spherical Metal Shells For two concentric spherical shells with radii $a$ and $b$ ($b>a$): $C = 4\pi\epsilon_0 \frac{ab}{b-a}$ Poisson's Equation & Laplace's Equation Combining $\nabla \cdot \vec{E} = \rho/\epsilon_0$ and $\vec{E} = -\nabla V$ yields Poisson's Equation : $\nabla^2 V = -\frac{\rho}{\epsilon_0}$ In regions where there is no charge ($\rho = 0$), Poisson's equation reduces to Laplace's Equation : $\nabla^2 V = 0$ Laplace's Equation in Different Coordinates Rectangular: $\frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial y^2} + \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial z^2} = 0$ Cylindrical: $\frac{1}{\rho} \frac{\partial}{\partial \rho} \left( \rho \frac{\partial V}{\partial \rho} \right) + \frac{1}{\rho^2} \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial \phi^2} + \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial z^2} = 0$ Spherical: $\frac{1}{r^2} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} \left( r^2 \frac{\partial V}{\partial r} \right) + \frac{1}{r^2 \sin\theta} \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta} \left( \sin\theta \frac{\partial V}{\partial \theta} \right) + \frac{1}{r^2 \sin^2\theta} \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial \phi^2} = 0$ Uniqueness Theorem If a solution to Laplace's equation can be found that satisfies the boundary conditions, then the solution is unique. Techniques for solving: Method of Images, Separation of Variables, Multipole Expansion. Image Problem Point charge near a grounded conducting plane: The field can be found by replacing the plane with an "image charge" of opposite sign at an equal distance behind the plane. Point charge near a grounded conducting sphere: The field can be found by replacing the sphere with an image charge inside the sphere. Multiple Images: For complex geometries (e.g., two intersecting planes), multiple image charges might be needed. Dielectric Polarization Dielectrics: Materials where all charges are attached to specific atoms or molecules. Polarization ($\vec{P}$): The dipole moment per unit volume. It describes how the material responds to an electric field. Microscopic displacements (stretching and rotating) of charges in atoms/molecules. Atomic Polarizability ($\alpha$): For a neutral atom, $\vec{p} = \alpha \vec{E}$. Electric Displacement ($\vec{D}$) In a dielectric medium, the electric displacement field $\vec{D}$ is defined as: $\vec{D} = \epsilon_0 \vec{E} + \vec{P}$ For linear dielectrics, $\vec{P} = \epsilon_0 \chi_e \vec{E}$, where $\chi_e$ is the electric susceptibility . Thus, $\vec{D} = \epsilon_0 (1 + \chi_e) \vec{E} = \epsilon \vec{E}$ $\epsilon = \epsilon_0 (1 + \chi_e)$ is the permittivity of the material . $\epsilon_r = 1 + \chi_e = \epsilon/\epsilon_0$ is the relative permittivity or dielectric constant . Bound Charges Polarization $\vec{P}$ can produce bound volume charge density $\rho_b$ and bound surface charge density $\sigma_b$. Bound volume charge density: $\rho_b = -\nabla \cdot \vec{P}$ Bound surface charge density: $\sigma_b = \vec{P} \cdot \hat{n}$ Gauss's Law in the Presence of Dielectrics The total charge density is $\rho = \rho_b + \rho_f$, where $\rho_f$ is the free charge density. Gauss's Law becomes $\nabla \cdot \vec{D} = \rho_f$ And $\oint_S \vec{D} \cdot d\vec{a} = Q_{f,enc}$ Energy in Dielectric Systems The energy stored in a dielectric system is: $W = \frac{1}{2} \int_V \vec{D} \cdot \vec{E} d\tau = \frac{1}{2} \int_V \epsilon E^2 d\tau$