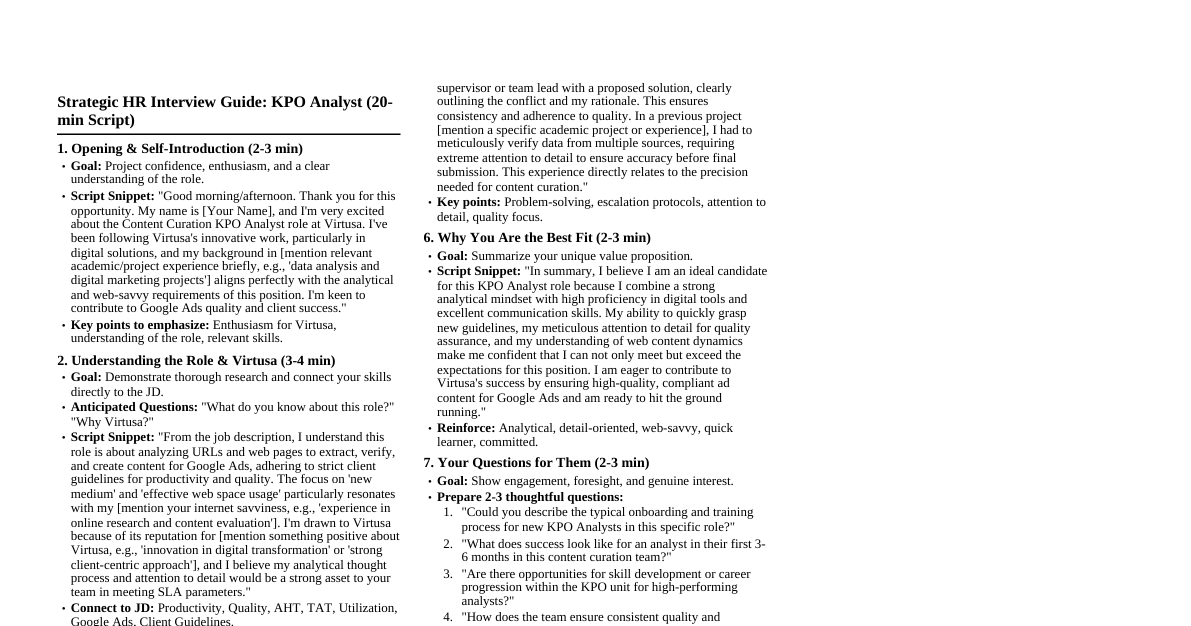

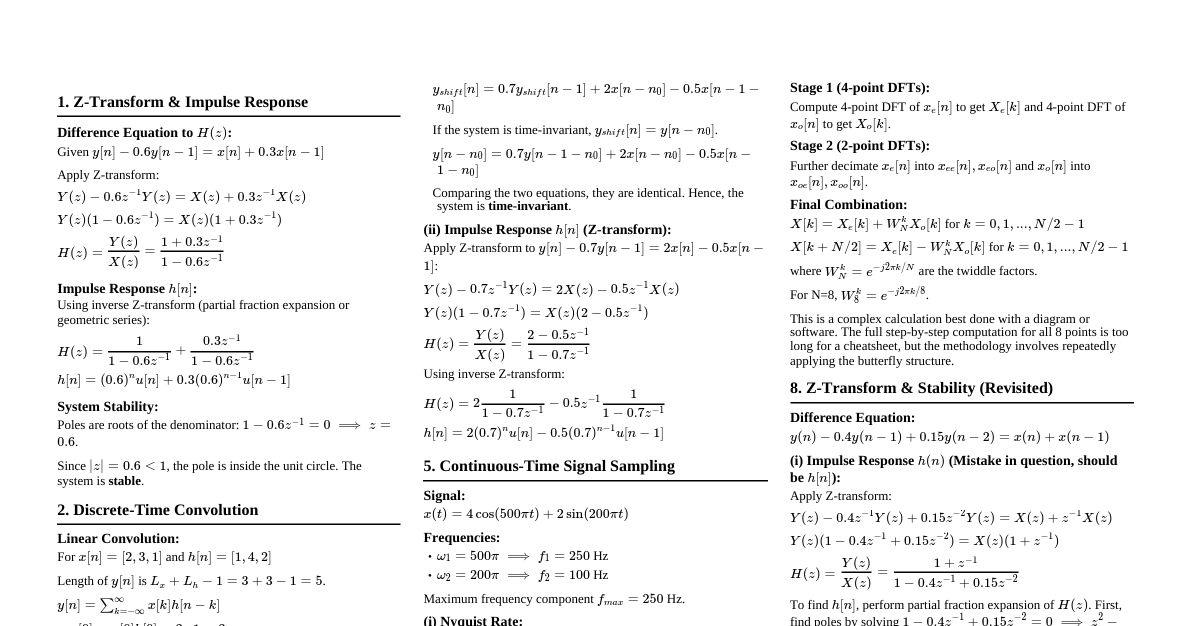

Explaining Derivations: NBFM Q1: Why small angle approximation in NBFM? Physical reason: NBFM intentionally keeps frequency deviation small (Δf = 2-3 kHz), so $\beta = \Delta f / f_m$ is naturally small. Mathematical justification: For $\beta $\cos(\beta \sin \omega_m t) \approx 1$ (error $ $\sin(\beta \sin \omega_m t) \approx \beta \sin \omega_m t$ Practical benefit: Simplifies NBFM to 3 spectral components (carrier + 2 sidebands), similar to AM, with bandwidth $\approx 2 f_m$. When it breaks: If $\beta \ge 0.5$, higher-order terms (Bessel functions) become significant, leading to WBFM. Conclusion: Approximation is valid due to intentional small deviation for bandwidth efficiency. Q2: NBFM derivation from general FM equation Starting point: $s(t) = A_c \cos[\omega_c t + \beta \sin \omega_m t]$ Step 1 - Trig Identity: $\cos(A+B) = \cos A \cos B - \sin A \sin B$ $s(t) = A_c[\cos \omega_c t \cdot \cos(\beta \sin \omega_m t) - \sin \omega_c t \cdot \sin(\beta \sin \omega_m t)]$ Step 2 - Small Angle Approx ($\beta \ll 1$): $\cos(\beta \sin \omega_m t) \approx 1$ $\sin(\beta \sin \omega_m t) \approx \beta \sin \omega_m t$ Step 3 - Substitute: $s(t) = A_c[\cos \omega_c t \cdot 1 - \sin \omega_c t \cdot \beta \sin \omega_m t]$ $s(t) = A_c \cos \omega_c t - A_c \beta \sin \omega_c t \sin \omega_m t$ Step 4 - Product-to-Sum: $\sin A \sin B = \frac{1}{2}[\cos(A-B) - \cos(A+B)]$ $\sin \omega_c t \sin \omega_m t = \frac{1}{2}[\cos(\omega_c-\omega_m)t - \cos(\omega_c+\omega_m)t]$ Final result: $s(t) = A_c \cos \omega_c t - (\frac{A_c \beta}{2})[\cos(\omega_c-\omega_m)t - \cos(\omega_c+\omega_m)t]$ Carrier at $f_c$ Lower Sideband at $f_c - f_m$ Upper Sideband at $f_c + f_m$ Bandwidth $= 2 f_m$ Q3: Physical relationship between NBPM and NBFM PM: Message $m(t)$ directly controls phase $\phi(t) = \delta \sin \omega_m t$. Phase changes instantly with message amplitude. FM: Message $m(t)$ controls frequency $f_i(t) = f_c + \Delta f \sin \omega_m t$. Frequency is the rate of change of phase: $f = \frac{1}{2\pi} \frac{d\phi}{dt}$. Connection: If $\phi(t) = \delta \sin \omega_m t$, then $f_i = f_c + \frac{1}{2\pi} \frac{d}{dt}(\delta \sin \omega_m t) = f_c + (\frac{\delta \omega_m}{2\pi}) \cos \omega_m t = f_c + \Delta f \cos \omega_m t$. Key Insight: PM with message $m(t)$ is equivalent to NBFM with message $dm/dt$. They are 90° phase-shifted (sin vs cos). $\Delta f = f_m \cdot \delta$. Practical Implication: An integrator before an FM modulator generates PM, and a differentiator before a PM modulator generates FM (used in Armstrong method). Conclusion: NBPM and NBFM are both angle modulation, differing in whether the message controls phase directly or its derivative (frequency). Justifying Comparisons Q4: Why NBFM has poor noise performance Fundamental Principle: FM's noise immunity comes from the frequency discriminator, which converts frequency variations to amplitude. Wider frequency deviation ($ \Delta f $) leads to better noise suppression. Why NBFM Suffers: Small Deviation ($\Delta f \approx 2.5$ kHz): Noise-induced frequency shifts are comparable to the signal's small deviation. Mathematical: SNR improvement in FM is proportional to $\beta^2$. For NBFM ($\beta = 0.3$), improvement is low, often worse than AM. Physical Analogy: Narrow track (NBFM) vs. wide track (WBFM) for a ball (signal) under vibrations (noise). Small vibrations significantly affect the ball on the narrow track. Threshold Effect: NBFM has a higher threshold SNR (~12 dB) compared to WBFM (~8 dB), meaning it breaks down sooner in noisy conditions. Conclusion: NBFM sacrifices noise immunity for bandwidth efficiency, a deliberate trade-off. Q5: Why NBFM for aviation instead of SSB? Why NOT SSB: Tuning Precision: SSB requires $\pm 50$ Hz accuracy, unreliable with aircraft vibration, temperature, Doppler shift. Equipment Complexity: SSB needs coherent detection, stable oscillators, leading to more failure points. Aviation prioritizes KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid). Graceful Degradation: NBFM degrades gradually to noise. SSB fails abruptly with frequency error. Partially degraded comms is vital in emergencies. Standardization: Global aviation uses NBFM for decades; changing it is a massive, costly undertaking. Why NBFM is BETTER: Constant Envelope: Allows efficient Class C power amplifiers (60-80% efficient), crucial for limited aircraft power (e.g., battery backup). SSB needs inefficient linear PAs. Simple Implementation: Discriminator demodulators are robust and simple, working in extreme conditions. Bandwidth Adequate: VHF aviation band (118-137 MHz) has 760 channels at 25 kHz spacing, sufficient for global air traffic. Conclusion: Aviation prioritizes safety, reliability, and standardization over theoretical bandwidth efficiency. Q6: SSB vs. QAM bandwidth efficiency contradiction Apparent Contradiction: SSB is most bandwidth-efficient for analog, but QAM carries more bits/Hz. Resolution: Analog Signals (e.g., Voice): SSB is optimal because it transmits the source bandwidth directly (3.1 kHz for voice). AM/NBFM require $2 \times$ source bandwidth. Digital Signals (e.g., Data): QAM achieves higher spectral efficiency by encoding multiple bits per symbol (e.g., 256-QAM = 8 bits/symbol). This is possible due to: Digital compression (e.g., voice from 64 kbps to 8 kbps). Error tolerance (FEC, retransmission). High SNR availability in modern systems. Comparison: For analog voice: SSB wins (3 kHz vs. ~16 kHz for digital voice + QPSK). For data capacity: QAM wins (scales to Gbps). Conclusion: SSB is most efficient for continuous analog signals. QAM is most efficient for discrete digital signals. They are optimized for different problem domains. Defending Application Choices Q7: Why NBFM in marine comms with powerful generators? Not about Power, but Spectrum Allocation & Regulations: Regulatory Constraints: ITU allocates marine VHF (156-174 MHz) with 25 kHz channel spacing. WBFM needs 200 kHz, allowing only 90 channels. NBFM (25 kHz) allows 720 channels, essential for international, regional, and distress operations. International Coordination: Channel 16 (156.8 MHz) is international distress. All ships must use the same standard. Equipment Cost: Global fleet replacement would cost billions. Operational Requirements: Voice Quality "Good Enough": Marine comms are operational, not entertainment. NBFM's 12-15 dB SINAD is perfectly intelligible. Propagation: VHF marine is typically 20-50 km line-of-sight. WBFM's noise advantage is often wasted as atmospheric/engine noise dominates. Conclusion: Engineering decisions are constrained by regulations, installed base, spectrum scarcity, and the "good enough" principle, not just available power. Q8: Why 5G uses QAM for data but QPSK for control channels? Control Channel Requirements: Must Reach ALL Users: Even cell-edge users with poor SNR (5-10 dB). QPSK works down to 4-5 dB SNR; 256-QAM needs 30+ dB SNR. Cannot Tolerate Errors: Control carries critical info (handover, paging). One bit error can cause call drops. QPSK is robust. Coverage Priority: Control channel defines cell coverage. QPSK extends coverage radius by ~30%. Data Channel Requirements: High Throughput: For streaming, downloads. Users near towers (good SNR) use high-order QAM (e.g., 256-QAM for 8 bits/symbol vs. QPSK's 2 bits/symbol). Can Tolerate Some Errors: TCP/IP retransmits lost packets. Video codecs tolerate some loss. Efficiency Priority: Maximizing bits/Hz is economically vital for spectrum costs. Adaptive Modulation: Data channels adapt QAM order based on each user's SNR. Control channels are broadcast and must use the most robust modulation (QPSK) for all users. Conclusion: 5G optimizes overall system performance by using different modulations for different priorities: QPSK for control (reliability, coverage), QAM for data (efficiency, throughput). Q9: My home WiFi works through concrete walls, despite QAM needing high SNR? Real-World Complexity vs. Ideal Theory: Your WiFi employs several techniques: Adaptive Rate Selection: WiFi constantly adapts its QAM order (e.g., 1024-QAM near router, 16-QAM/QPSK through walls) based on real-time SNR. Frequency Selection: 2.4 GHz (better wall penetration) vs. 5/6 GHz (higher speed, worse penetration). Devices automatically switch. MIMO (Multiple Antennas): Uses multipath diversity (signals reflecting off walls) to combine multiple copies and improve effective SNR. OFDM Subcarrier Adaptation: WiFi uses OFDM, where each subcarrier can use a different QAM order based on its individual SNR, maximizing efficiency across the band. Forward Error Correction (FEC): Adds redundancy to correct errors without retransmission, effectively improving SNR by ~3 dB. Power Control: Routers can boost transmit power when needed to penetrate obstacles. Conclusion: WiFi works through walls because it's a smart, adaptive system that detects poor SNR and switches to lower-order QAM, uses appropriate frequencies, leverages MIMO, and employs error correction. The user experiences slower speed, while the system constantly juggles modulation schemes to maintain connection. Challenging Understanding Q10: NBFM $\beta Apparent Contradiction: Textbook $\beta Resolution: "Narrowband" has two definitions: Theoretical: $\beta Practical: $\beta Actual Bandwidth: For $\beta = 0.83$, Bessel functions show the 2nd sidebands are marginal, 3rd negligible. Carson's rule: $BW = 2(\Delta f + f_m) = 2(2.5+3) = 11$ kHz, which fits in a 12.5 kHz channel. Why $\beta = 0.83$ is "narrowband": It's a relative definition. Compared to WBFM ($\beta = 5$, BW $\approx 180$ kHz), 11 kHz is indeed narrow. Historical Context: Early NBFM systems used $\beta = 0.8-1.0$ as a practical compromise for audio quality and bandwidth. Conclusion: The $\beta Q11: SSB 100% power efficiency, but transmitter uses DC power. Where does 'wasted' power go? Critical Distinction: Two different efficiencies: Modulation Efficiency (what I meant): Percentage of RF power carrying information. AM (DSB-FC): 33% (carrier wastes 2/3 power). SSB-SC: 100% (all transmitted RF power carries information). Power Amplifier (PA) Efficiency: Percentage of DC input converted to RF output. This depends on PA class, not modulation. Class A: 25-30% (linear, for SSB, AM, QAM) Class B: 50-60% (linear, for SSB) Class C: 60-80% (non-linear, for NBFM, WBFM - constant envelope) Where Wasted Power Goes: Mostly converted to heat in the PA transistors and other circuit components. This is why transmitters need cooling. SSB requires Linear PA: SSB has a variable envelope, so it needs linear PAs (Class A/B) to avoid distortion, which are less efficient. NBFM Advantage: NBFM has a constant envelope, allowing it to use highly efficient Class C PAs (75% efficient). Overall Efficiency Comparison (DC input for 100W RF carrying information): AM: 400W DC (due to carrier waste and Class C PA) SSB: 167W DC (100% modulation efficient, but Class B PA) NBFM: 133W DC (100% modulation efficient, and Class C PA) Conclusion: While SSB has 100% modulation efficiency, NBFM often has better overall DC-to-RF efficiency due to its ability to use more efficient Class C PAs. This is why handheld radios often use NBFM. Q12: If QAM is complex, why not just use many parallel BPSK channels? Your Proposal: Parallel BPSK (Frequency Division Multiplexing - FDM): Fails to achieve high throughput: e.g., 50 parallel BPSK channels in 100 MHz might only yield 50 Mbps, far from 1 Gbps. Why Parallel BPSK Fails: Guard Bands Waste Spectrum: Each BPSK channel needs separation, wasting significant bandwidth. QAM with OFDM uses orthogonal subcarriers, requiring no guard bands between them. Hardware Multiplication: 50 separate BPSK channels would require 50 sets of oscillators, mixers, filters, and demodulators, making it more expensive and power-hungry than a single QAM system with DSP. Synchronization Nightmare: Each BPSK channel would need its own carrier and symbol timing recovery, leading to immense complexity. QAM requires single synchronization. Lower Spectral Efficiency: BPSK is 1 bit/Hz. 256-QAM is 8 bits/Hz, making it 8 times more efficient. QAM Advantages: Spectral Efficiency: Uses amplitude and phase dimensions simultaneously. Hardware Efficiency: Modern DSP makes a single complex QAM modulator cheaper and more power-efficient than many simple modulators. Adaptive: QAM with OFDM can adapt modulation order per subcarrier based on channel conditions, maximizing throughput. Conclusion: While parallel BPSK seems simple, it's spectrally inefficient, hardware-intensive, and complex to synchronize. QAM, despite its individual complexity, enables much higher spectral efficiency and is more practical and cost-effective for high-data-rate systems due to DSP advancements and OFDM. Synthesis Questions Q13: Design communication system for disaster relief: 100 km range, 50 users, voice only, limited power. Step 1: Analyze Requirements: Range: 100 km (long) Users: 50 (moderate capacity) Application: Voice only (reliability critical) Power: Limited (battery-operated) Context: Disaster relief (no infrastructure, rugged, simple operation) Step 2: Frequency Band Selection: Reject VHF/UHF (line-of-sight). Choose HF (3-30 MHz) for proven 100+ km ionospheric propagation. (e.g., 7 MHz or 14 MHz band). Step 3: Modulation Selection: AM: Reject (poor power efficiency). NBFM: Reject (poor HF propagation characteristics). Digital (P25, DMR): Reject (cliff effect, complexity, latency). Select SSB (Single Sideband): Best power efficiency (100% modulation, 60% PA). Best bandwidth efficiency (3 kHz/channel). Excellent HF propagation. Proven reliable in emergency communications (EMCOMM). Step 4: System Design Details: Frequency: 7.2-7.3 MHz (40m amateur band). 50 users, 3 kHz/channel. Power: 10-20W PEP. 20W SSB $\approx$ 60W carrier equivalent. 12V 20Ah battery provides $\approx 30$ hours operation with typical usage. Link Budget: 20W (43 dBm) + 3 dBi antenna, path loss 40-60 dB (ionospheric). Provides excellent link margin. Equipment: Portable HF SSB transceiver (e.g., $500-800), 10m whip or wire dipole antenna. Step 5: Operational Considerations: Training needed for SSB tuning (15-30 min). Advantages: No infrastructure, 100 km range, proven tech, power efficient, interoperable with amateur EMCOMM. Disadvantages (accepted trade-offs): Tuning skill, propagation variability (mitigate with multiple frequencies), potential interference (mitigate with frequency coordination). Conclusion: SSB in the HF band is the most appropriate choice due to its long-range capability, power efficiency, and proven reliability in infrastructure-down emergency scenarios, prioritizing essential communication over advanced features. Q14: Why cellular technology keeps changing (2G→5G) but aviation radio stays NBFM for 80 years? CELLULAR: Innovation-Driven Economics: Market pressure from user demand (voice $\to$ mobile internet $\to$ video $\to$ AR/VR) drives exponential data growth. Competitive advantage and revenue justify massive investments in new technologies. Technology: Moore's Law enables powerful DSP chips, making advanced modulations viable and cheaper. Lifecycle: Short equipment lifespan (2-3 years for phones, 5-10 for towers) allows rapid upgrades. Spectrum: Scarcity and cost drive efficiency (e.g., 5G 256-QAM is $16 \times$ more efficient than 2G GMSK). AVIATION: Stability-Driven Safety First: NBFM has 70+ years of proven reliability. Any change is subject to rigorous, decade-long certification processes (FAA, EASA, ICAO). No acceptable risk to human life for "better modulation". Global Interoperability: Aircraft cross many countries, requiring a single, globally harmonized standard. Changing this takes decades of international coordination. Equipment Lifespan: Aircraft (30-40 years) and avionics are certified for long periods. Rapid obsolescence is impractical and costly ($200+ billion for global fleet replacement). Backwards Compatibility: Old and new aircraft must communicate seamlessly; communication failure is unacceptable. Conservative Culture: "Safety first, efficiency second" vs. "Move fast and break things" in cellular. The Paradox: Cellular's rapid innovation is acceptable because call drops are annoying, not fatal. Aviation's slow innovation is necessary because radio failure can be fatal. Hybrid Future: Aviation is slowly integrating digital data links (e.g., ADS-B, VDL) alongside NBFM, with analog serving as a critical backup. Conclusion: Different industries have different optimization goals. Cellular prioritizes speed, capacity, and features. Aviation prioritizes safety, reliability, and longevity. Both use appropriate modulation for their context, illustrating that technical superiority doesn't guarantee adoption. Deep Concept Questions Q15: Physical meaning of 'modulation index' ($\beta$) in FM. Formula: $\beta = \Delta f / f_m = (\text{Max Frequency Deviation}) / (\text{Modulating Frequency})$. Physical Phenomenon: Imagine a pendulum swinging at a constant frequency ($f_c$). Modulating (applying a message) is like "pushing" the pendulum to swing faster or slower. Small $\beta$ (NBFM): "Gentle pushes." The pendulum's frequency varies slowly and slightly compared to its natural rhythm. The carrier's frequency has tiny excursions. Large $\beta$ (WBFM): "Strong pushes." The pendulum's frequency varies dramatically and rapidly. The carrier "swings wildly" in frequency. Spectral Interpretation: Small $\beta ( Gentle frequency wobble creates only first-order sidebands ($f_c \pm f_m$). Spectrum is narrow, like AM. Large $\beta (>1)$: Dramatic frequency swinging creates many sidebands ($f_c \pm n f_m$). Spectrum is wide. The Bessel functions $J_n(\beta)$ describe the amplitude of these sidebands. As $\beta$ increases, the carrier amplitude $J_0(\beta)$ decreases, and higher-order sidebands become significant. Why Engineers Care: Bandwidth: $\beta$ directly determines occupied bandwidth (Carson's Rule: $BW \approx 2 f_m (\beta + 1)$). Larger $\beta \to$ wider bandwidth. Noise Immunity: SNR improvement is proportional to $\beta^2$. Larger $\beta \to$ better noise performance. Trade-off: $\beta$ is the design parameter that balances bandwidth efficiency (small $\beta$) and noise immunity (large $\beta$). Conclusion: $\beta$ physically represents "how much the carrier frequency swings relative to how fast the message changes." It's the single most important parameter in FM design, dictating both spectral width and noise performance.