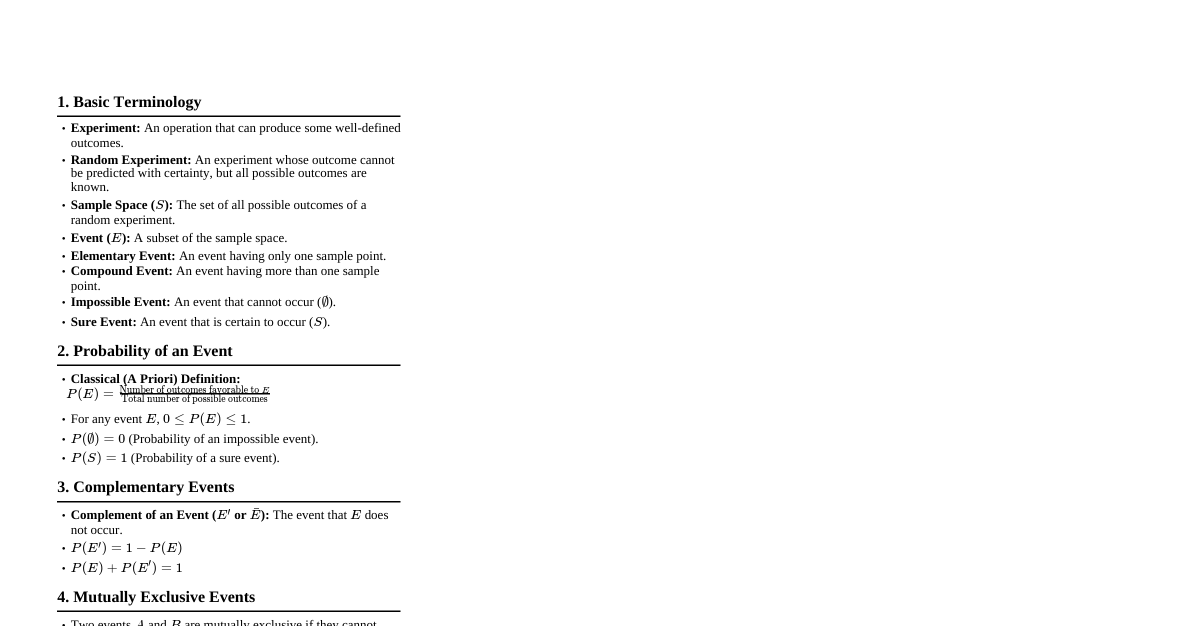

### Probability Theory - Probability theory began in the 17th century, focusing on games of chance. - The **classical definition of probability** emerged in the 19th century. - It's widely applicable in situations involving **uncertainty** (repeated trials leading to differing outcomes). - The core concept is a **probability space** (or probability model). ### Classical Probability - **Sample Space (S):** Set of all possible outcomes. - **Definition:** For an event A, the probability is: $$P(A) = \frac{\text{(Favourable) number of cases in A}}{\text{Total number of cases}} = \frac{\#A}{\#S}$$ - **Example:** Rolling a die, probability of getting 3 is $1/6$. - **Limitation:** Cannot be used when $\#A$ or $\#S$ are infinite (e.g., hitting a target in concentric circles). - A.N. Kolmogorov (1903-1987) laid the foundations of modern probability theory with the **axiomatic definition** (1933), combining sample space and measure theory. ### Countability and Uncountability - **Equivalent Sets (A ~ B):** A bijection exists from set A to set B. - **For any set A:** - **Countable:** $A \sim \mathbb{N}$ (can be written as a sequence of distinct terms $\{x_n\}$). - **Atmost Countable:** A is finite or countable. - **Uncountable:** A is not atmost countable. - **Example:** $\mathbb{Z}$ (integers) is countable. - **Summary of Results:** - Every subset of an atmost countable set is again atmost countable. - A sequence of atmost countable sets has an atmost countable union. - The Cartesian product of a finite number of atmost countable sets is atmost countable. - The set of rationals ($\mathbb{Q}$) is countable. - The set of all binary sequences is uncountable. - The interval $[0, 1]$ is uncountable. - The set of real numbers ($\mathbb{R}$) is uncountable. - The set of irrational numbers ($\mathbb{Q}^c$) is uncountable. - Any interval is uncountable. ### Random Experiment An experiment is **random** if it satisfies three properties: 1. All possible outcomes are known in advance. 2. The outcome of any particular performance is not known in advance. 3. The experiment can be repeated under identical conditions. - **Examples:** Tossing a coin, tossing a coin until the first head appears. - **Not random:** Measuring the distance between two cities (outcome is known). ### Sample Space - **Definition:** The collection of all possible outcomes of a random experiment, denoted by $S$. - **Examples:** - Tossing a coin: $S = \{H, T\}$ (Finite). - Tossing a coin until first head: $S = \{H, TH, TTH, ...\}$ (Countable). - Measuring time: $S = (0, \infty)$ (Uncountable). ### $\sigma$-algebra (or $\sigma$-field) - **Definition:** A non-empty collection $\mathcal{F}$ of subsets of $S$ is a $\sigma$-algebra if: 1. $S \in \mathcal{F}$ 2. If $A \in \mathcal{F}$, then $A^c \in \mathcal{F}$ (closure under complementation). 3. If $A_1, A_2, ... \in \mathcal{F}$, then $\bigcup_{i=1}^\infty A_i \in \mathcal{F}$ (closure under countable unions). - **Properties:** - The smallest $\sigma$-field is $\mathcal{F} = \{\emptyset, S\}$ (trivial one). - The largest $\sigma$-field is $\mathcal{F} = \mathcal{P}(S)$ (the power set). - A $\sigma$-field is a field, but not every field is a $\sigma$-field. ### Events - **Definition:** A set $E \subseteq S$ is an **event** with respect to a $\sigma$-field $\mathcal{F}$ if $E \in \mathcal{F}$. - "The event $E$ occurs" if the outcome of the experiment is in $E$. - The $\sigma$-field $\mathcal{F}$ is essentially the **'event space'**. ### Axiomatic Definition of Probability - **Definition:** Given a non-empty sample space $S$ and a $\sigma$-field $\mathcal{F}$ of subsets of $S$, a function $P: \mathcal{F} \to \mathbb{R}$ is a **probability measure** if it satisfies the following axioms: 1. $P(E) \ge 0$ for all $E \in \mathcal{F}$. 2. $P(S) = 1$. 3. **Countable Additivity:** If $E_1, E_2, ... \in \mathcal{F}$ are mutually exclusive (disjoint) events, then: $$P\left(\bigcup_{i=1}^\infty E_i\right) = \sum_{i=1}^\infty P(E_i)$$ - **Probability Space:** The triplet $(S, \mathcal{F}, P)$ is called a probability space. ### Properties of Probability For $E, E_1, E_2, ..., E_n \in \mathcal{F}$: 1. $0 \le P(E) \le 1$. 2. $P(\emptyset) = 0$. 3. If $E_1, ..., E_n$ are $n$ disjoint events, then $P\left(\bigcup_{i=1}^n E_i\right) = \sum_{i=1}^n P(E_i)$. 4. $P(E^c) = 1 - P(E)$. 5. **Monotonicity:** If $E_1 \subseteq E_2$, then $P(E_1) \le P(E_2)$. 6. If $E_1 \subseteq E_2$, then $P(E_2 - E_1) = P(E_2) - P(E_1)$. 7. **Principle of Inclusion and Exclusion:** $P(E_1 \cup E_2) = P(E_1) + P(E_2) - P(E_1 \cap E_2)$. (Can be extended to $n$ events). 8. $P(E_1 \cup E_2) \le P(E_1) + P(E_2)$. (Can be extended to $n$ events). ### Remarks on Probability - An elementary event is a singleton $\{\omega\} \in S$. - If $S$ is finite and $\mathcal{F} = \mathcal{P}(S)$, assign probability to each elementary event. If events are equally likely, it leads to classical definition. - If $S$ is countably infinite and $\mathcal{F} = \mathcal{P}(S)$, assign probability to each elementary event. Cannot assign equal probability in this case. - If $S$ is uncountable and $\mathcal{F} = \mathcal{P}(S)$, cannot make an equally likely assignment or assign positive probability to each elementary event without violating $P(S)=1$. ### Continuity of Probability - **Increasing Sequence of Events:** $\{E_n\}_{n \ge 1}$ is increasing if $E_n \subseteq E_{n+1}$. - $\lim_{n \to \infty} E_n = \bigcup_{n=1}^\infty E_n$. - **Decreasing Sequence of Events:** $\{E_n\}_{n \ge 1}$ is decreasing if $E_{n+1} \subseteq E_n$. - $\lim_{n \to \infty} E_n = \bigcap_{n=1}^\infty E_n$. - **Theorem (Continuity from Below):** If $\{E_n\}_{n \ge 1}$ is an increasing sequence, then $P(\lim_{n \to \infty} E_n) = \lim_{n \to \infty} P(E_n)$. - **Theorem (Continuity from Above):** If $\{E_n\}_{n \ge 1}$ is a decreasing sequence, then $P(\lim_{n \to \infty} E_n) = \lim_{n \to \infty} P(E_n)$. - Finite additivity and continuity implies countable additivity. - For any sequence of events $\{E_n\}_{n \ge 1}$, $P\left(\bigcup_{n=1}^\infty E_n\right) \le \sum_{n=1}^\infty P(E_n)$. ### Counting Problems in Probability - **Sampling:** Drawing a sample "at random" where each element has equal chance of being chosen. - **With and Without Replacement:** - **With replacement:** Repetition is allowed (object put back after draw). - **Without replacement:** Repetition is not allowed. - **Ordered or Unordered:** - **Ordered:** Order matters. - **Unordered:** Order does not matter. #### Counting Results for the Four Sampling Methods Assume a set A with $n$ elements, drawing $k$ elements: | Method | Formula | | :----------------------------------- | :----------------------------------------- | | Ordered sampling with replacement | $n^k$ | | Ordered sampling without replacement | $^nP_k = \frac{n!}{(n-k)!}$ | | Unordered sampling without replacement | $\binom{n}{k} = \frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}$ | | Unordered sampling with replacement | $\binom{n+k-1}{k}$ | - $^nP_k = n \times (n-1) \times ... \times (n-k+1)$: k-permutation. - $\binom{n}{k}$: Number of k-element subsets. - $^nP_k = \binom{n}{k} \times k!$. ### Conditional Probability - **Definition:** Given a probability space $(S, \mathcal{F}, P)$ and events $A, H \in \mathcal{F}$ such that $P(H) > 0$. The **conditional probability of A given H** is: $$P(A|H) = \frac{P(A \cap H)}{P(H)}$$ - **Multiplication Rule:** - $P(A \cap B) = P(A)P(B|A)$ if $P(A) > 0$. - $P(A \cap B) = P(B)P(A|B)$ if $P(B) > 0$. - **Mutually Exclusive Events:** A collection $\{E_1, E_2, ...\}$ is mutually exclusive if $E_i \cap E_j = \emptyset$ for $i \ne j$. - **Exhaustive Events:** A collection $\{E_i\}$ is exhaustive if $\bigcup_i E_i = S$. - **Partition:** A collection $\{E_i\}$ is a partition of $S$ if it is both mutually exclusive and exhaustive. #### Conditional Probability Theorems - **Theorem of Total Probability:** Given a partition $\{E_1, E_2, ...\}$ of $S$ with $P(E_i) > 0$, for any event $E$: $$P(E) = \sum_i P(E|E_i)P(E_i)$$ - **Bayes' Theorem:** Given a partition $\{E_1, E_2, ...\}$ of $S$ with $P(E_i) > 0$, for any event $E$ with $P(E) > 0$: $$P(E_i|E) = \frac{P(E|E_i)P(E_i)}{\sum_j P(E|E_j)P(E_j)}$$ ### Independence - **Definition:** Given $(S, \mathcal{F}, P)$, two events $A$ and $B$ are: - **Negatively Associated:** $P(A \cap B) P(A)P(B)$. - **Independent:** $P(A \cap B) = P(A)P(B)$. - Independence is about whether the probability of one event is affected by the occurrence of another. - If $P(B) > 0$, $A$ and $B$ are independent iff $P(A|B) = P(A)$. - If $P(B^c) > 0$, $A$ and $B$ are independent iff $P(A|B^c) = P(A)$. - If $P(B) = 0$ or $1$, $A$ and $B$ are independent. - Any event $A$ is independent of $S$ and $\emptyset$. - **Theorem:** If $A$ and $B$ are independent, so are $A$ and $B^c$, $A^c$ and $B$, $A^c$ and $B^c$. #### Types of Independence - **Pairwise Independent:** A countable collection of events $\{E_1, E_2, ...\}$ such that $E_i$ and $E_j$ are independent for $i \ne j$. - **Independent (Mutually Independent):** A finite collection of events $\{E_1, E_2, ..., E_n\}$ such that for any sub-collection $E_{n_1}, ..., E_{n_k}$: $$P\left(\bigcap_{i=1}^k E_{n_i}\right) = \prod_{i=1}^k P(E_{n_i})$$ - A countable collection of events is independent if any finite sub-collection is independent. - **Remarks:** - To verify independence of $E_1, ..., E_n$, we must check $2^n - n - 1$ conditions. For $n=3$, this includes $P(E_1 \cap E_2) = P(E_1)P(E_2)$, $P(E_1 \cap E_3) = P(E_1)P(E_3)$, $P(E_2 \cap E_3) = P(E_2)P(E_3)$, and $P(E_1 \cap E_2 \cap E_3) = P(E_1)P(E_2)P(E_3)$. - Independence implies pairwise independence. - Pairwise independence does not imply independence. #### Conditional Independence - **Definition:** Given an event $C$, two events $A$ and $B$ are **conditionally independent** if $P(A \cap B|C) = P(A|C)P(B|C)$. ### Random Variables - **Definition:** Given a probability space $(S, \mathcal{F}, P)$, a **random variable (RV)** $X$ is a function from $S$ to $\mathbb{R}$ such that for all $x \in \mathbb{R}$: $$\{s \in S \mid X(s) \le x\} \in \mathcal{F}$$ This ensures that the probability $P(X \le x)$ is well-defined. - **Key Idea:** RVs map outcomes from the sample space (which can be abstract) to real numbers, making them easier to work with mathematically. ### Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) - **Definition:** Given $(S, \mathcal{F}, P)$ and an RV $X$ on $(S, \mathcal{F}, P)$, the **cumulative distribution function (CDF)** $F_X: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ is defined by: $$F_X(x) = P(X^{-1}(-\infty, x]) = P(\{s : X(s) \le x\}), \quad \forall x \in \mathbb{R}$$ - Often written as $F(x) = P(X \le x)$. - The CDF always lies in the interval $[0, 1]$. #### Properties of CDF A function $G: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ is a CDF if and only if it satisfies: 1. **Non-decreasing:** $F_X(x_1) \le F_X(x_2)$ for $x_1 \le x_2$. 2. **Right-continuous:** $\lim_{h \downarrow 0} F_X(x+h) = F_X(x)$ for all $x \in \mathbb{R}$. 3. **Limits:** - $\lim_{x \to -\infty} F_X(x) = 0$. - $\lim_{x \to \infty} F_X(x) = 1$. - **Additional Properties:** - $P(X=x) = F_X(x) - F_X(x^-)$, where $F_X(x^-) = \lim_{h \downarrow 0} F_X(x-h)$. - $P(a 0$, $x$ is an **atom** of the CDF. If there are no atoms, the CDF is continuous. ### Discrete Random Variables and Probability Mass Function (PMF) - **Definition:** An RV $X$ has a **discrete distribution** if there exists an atmost countable set $S_X \subset \mathbb{R}$ (called the **support** of $X$) such that $P(X=x) > 0$ for all $x \in S_X$ and $\sum_{x \in S_X} P(X=x) = 1$. - **Probability Mass Function (PMF):** A function $f_X: \mathbb{R} \to [0, 1]$ defined by: $$f_X(x) = \begin{cases} P(X=x) & \text{if } x \in S_X \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$ #### Properties of PMF For a function $h: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ to be a PMF: 1. $h(x) \ge 0$ for all $x \in \mathbb{R}$. 2. The set $D = \{x : h(x) > 0\}$ must be atmost countable. 3. $\sum_{x \in D} h(x) = 1$. - For a discrete RV $X$: - $F_X(x) = \sum_{y \in S_X, y \le x} f_X(y)$. - $f_X(x) = F_X(x) - F_X(x^-)$. #### Some Standard Discrete Distributions 1. **Degenerate Distribution:** $S_X = \{c\}$, $f_X(c) = 1$. 2. **Discrete Uniform Distribution:** $X \sim DU\{a_1, ..., a_n\}$. $S_X = \{a_1, ..., a_n\}$, $f_X(k) = 1/n$. 3. **Bernoulli Distribution:** $X \sim \text{Bernoulli}(p)$. $S_X = \{0, 1\}$, $f_X(0) = 1-p$, $f_X(1) = p$. (Single trial with success probability $p$). 4. **Binomial Distribution:** $X \sim \text{Bin}(n, p)$. $S_X = \{0, 1, ..., n\}$. Counts number of successes in $n$ independent Bernoulli trials. $$f_X(k) = \begin{cases} (1-p)^n & \text{if } k=0 \\ \binom{n}{k}p^k(1-p)^{n-k} & \text{if } k=1, ..., n-1 \\ p^n & \text{if } k=n \end{cases}$$ 5. **Hypergeometric Distribution:** $X \sim \text{HyperGeo}(m, n, N)$. $S_X = \{0, 1, ..., \min\{m, n\}\}$. Models number of successes in a sample *without replacement*. $$f_X(k) = \frac{\binom{m}{k}\binom{N-m}{n-k}}{\binom{N}{n}}$$ 6. **Geometric Distribution:** $X \sim \text{Geo}(p)$. $S_X = \{0, 1, 2, ...\}$ or $\{1, 2, 3, ...\}$. Counts number of failures before first success (or number of trials until first success). - $f_X(k) = p(1-p)^k$ for $k=0,1,2,...$ (failures before success). - $f_X(k) = p(1-p)^{k-1}$ for $k=1,2,3,...$ (trials until success). - **Memoryless Property:** $P(X > m+n | X > m) = P(X > n)$. 7. **Negative Binomial (Pascal) Distribution:** $X \sim NB(r, p)$. $S_X = \{0, 1, 2, ...\}$ or $\{r, r+1, ...\}$. Counts number of failures before the $r$-th success (or number of trials until $r$-th success). - $f_X(k) = \binom{r+k-1}{k}p^r(1-p)^k$ for $k=0,1,2,...$ (failures before $r$-th success). - $f_X(k) = \binom{k-1}{r-1}p^r(1-p)^{k-r}$ for $k=r, r+1, ...$ (trials until $r$-th success). 8. **Poisson Distribution:** $X \sim \text{Poi}(\lambda)$. $S_X = \{0, 1, 2, ...\}$. Models number of events in a fixed interval of time/space, given a mean rate $\lambda$. $$f_X(k) = \frac{e^{-\lambda}\lambda^k}{k!}$$ - Poisson PMF is a limiting case of binomial PMF. ### Continuous Random Variables and Probability Density Function (PDF) - **Definition:** An RV $X$ has a **continuous distribution** if there exists a non-negative integrable function $f_X: \mathbb{R} \to [0, \infty)$ (called the **Probability Density Function (PDF)**) such that: $$F_X(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x f_X(t)dt, \quad \forall x \in \mathbb{R}$$ - The set $S_X = \{x \in \mathbb{R} : f_X(x) > 0\}$ is called the **support** of $X$. #### Remarks on Continuous RVs 1. For a continuous RV $X$, $P(X=a) = 0$ for any $a \in \mathbb{R}$. 2. The CDF $F_X(x)$ of a continuous RV is continuous. 3. Wherever $F_X$ is differentiable, $f_X(x) = \frac{d}{dx}F_X(x)$. 4. The PDF is not unique at a finite number of points. 5. The support of a continuous RV is not unique. 6. $P(a \le X \le b) = P(a 0$. - $F_X(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x \frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{(t-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}} dt$. - $f_X(x) = \frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}}$. - $N(0, 1)$ is the **standard normal distribution**. - Standard normal PDF $f_X(x) = f_X(-x)$ (symmetric about 0). $F_X(-x) = 1 - F_X(x)$. - CDF and PDF of standard normal are denoted by $\Phi(\cdot)$ and $\phi(\cdot)$. - **Normal Approximation to Binomial:** Can be obtained as a continuous limit of the binomial (Central Limit Theorem). 4. **Gamma Distribution:** $X \sim \text{Gamma}(\alpha, \beta)$. $\alpha > 0, \beta > 0$. - $f_X(x) = \begin{cases} \frac{\beta^\alpha}{\Gamma(\alpha)} x^{\alpha-1}e^{-\beta x} & \text{if } x > 0 \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$ - $\Gamma(\alpha) = \int_0^\infty t^{\alpha-1}e^{-t}dt$ (gamma function). - If $\alpha = n$ (positive integer), $\Gamma(n) = (n-1)!$. - If $\alpha = 1$, it reduces to the exponential distribution. 5. **Beta Distribution:** $X \sim \text{Beta}(\alpha, \beta)$. $\alpha > 0, \beta > 0$. - $f_X(x) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{B(\alpha, \beta)} x^{\alpha-1}(1-x)^{\beta-1} & \text{if } 0 0, \beta > 0$. - $F_X(x) = \begin{cases} 1 - e^{-\alpha x^\beta} & \text{if } x \ge 0 \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$ - $f_X(x) = \begin{cases} \alpha\beta x^{\beta-1}e^{-\alpha x^\beta} & \text{if } x \ge 0 \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$ - Coincides with exponential if $\beta=1$. Used in survival analysis, reliability engineering. ### Random Variable Which Is Neither Discrete Nor Continuous - Some random variables can have CDFs that are a mix of continuous and jump components, meaning they are neither purely discrete nor purely continuous. - **Example:** A CDF that increases continuously over some intervals and has jumps at specific points. Such a CDF can often be expressed as a weighted average of a discrete CDF and a continuous CDF. ### Functions of a Random Variable - New RVs can be created by applying a function to an existing RV. - If $X$ is an RV and $g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ is a function, then $Y = g(X)$ is also an RV. - **Objective:** Find the distribution (CDF/PMF/PDF) of $Y$, given $g$ and the distribution of $X$. #### Techniques to Find the Distribution of $Y=g(X)$ 1. **Technique 1 (Using CDF Definition):** - Find $F_Y(y) = P(Y \le y) = P(g(X) \le y)$. - This technique is universal, applicable to all types of RVs. - The basic idea is to write the event $\{Y \le y\}$ as an event involving $X$, i.e., $\{X \in A_y\}$ for an appropriate set $A_y$. 2. **Technique 2 (Direct PMF/PDF - Applicable for Discrete RVs):** - If $X$ is discrete, $Y=g(X)$ is also discrete. - The support of $Y$ is $S_Y = \{g(x) : x \in S_X\}$. - The PMF of $Y$ is $f_Y(y) = \sum_{x \in A_y} f_X(x)$, where $A_y = \{x \in S_X : g(x) = y\}$. 3. **Technique 3 (Direct PDF - Applicable for Continuous RVs):** - If $X$ is continuous, $Y=g(X)$ can be discrete or continuous. - If $X$ is continuous with PDF $f_X(x)$ and support $S_X$, and $g: S_X \to \mathbb{R}$ is a differentiable function with $g'(x) \ne 0$ for all $x \in S_X$ (i.e., $g$ is strictly monotonic), then $Y=g(X)$ is continuous with PDF: $$f_Y(y) = f_X(g^{-1}(y)) \left|\frac{d}{dy}g^{-1}(y)\right| \quad \text{for } y \in g(S_X)$$ and $0$ otherwise. ### Expectation of Random Variables - The **expected value** or **mean** $E(X)$ is a fundamental one-number summary of an RV's behavior. - **For a Discrete RV** $X$ with PMF $f_X(x)$ and support $S_X$: $$E(X) = \sum_{x \in S_X} x f_X(x)$$ provided $\sum_{x \in S_X} |x|f_X(x) ### Moments - **$r$-th Raw Moment (about the origin):** $\mu'_r = E(X^r)$, for $r=1, 2, ...$. - $\mu'_1 = E(X)$ is the **mean**, denoted by $\mu$. - **$r$-th Central Moment (about the mean):** $\mu_r = E[(X - E(X))^r] = E[(X-\mu)^r]$, for $r=1, 2, ...$. - $\mu_2 = E[(X-\mu)^2]$ is the **variance**, denoted by $\text{Var}(X)$ or $\sigma^2$. - $\text{Var}(X) = E(X^2) - (E(X))^2 = E(X^2) - \mu^2$. - $\sigma = \sqrt{\text{Var}(X)}$ is the **standard deviation**. - **Coefficient of Skewness:** $\alpha_3 = \frac{\mu_3}{\sigma^3}$ (measure of symmetry). - **Kurtosis:** $\alpha_4 = \frac{\mu_4}{\sigma^4}$ (measure of tailedness). #### Results on Moments - If the $r$-th raw moment exists, then all $s$-th raw moments for $s ### Variance Variance of some standard distributions: 1. **Binomial $\text{Bin}(n, p)$:** $np(1-p)$. 2. **Poisson $\text{Poi}(\lambda)$:** $\lambda$. 3. **Geometric $\text{Geo}(p)$:** $(1-p)/p^2$. 4. **Uniform $U(a, b)$:** $(b-a)^2/12$. 5. **Normal $N(\mu, \sigma^2)$:** $\sigma^2$. 6. **Exponential $\text{Exp}(\lambda)$:** $1/\lambda^2$. 7. **Gamma $\text{Gamma}(\alpha, \beta)$:** $\alpha/\beta^2$. ### Moment Generating Function (MGF) - **Definition:** The **Moment Generating Function (MGF)** of an RV $X$ is defined by: $$M_X(t) = E(e^{tX})$$ provided the expectation exists in a neighborhood of the origin (i.e., for $t \in (-a, a)$ for some $a > 0$). - **MGF and Moments:** If $M_X(t)$ exists for $t \in (-a, a)$, then the $k$-th derivative of $M_X(t)$ at $t=0$ gives the $k$-th raw moment: $$E(X^k) = \left.\frac{d^k}{dt^k}M_X(t)\right|_{t=0}$$ - **Uniqueness Theorem:** The MGF uniquely determines a CDF. If two RVs have the same MGF, they have the same distribution. - The converse is not true: moments of all orders may exist, but the MGF may not. #### MGFs of Standard Distributions 1. **Binomial $\text{Bin}(n, p)$:** $M_X(t) = (1-p+pe^t)^n$. 2. **Exponential $\text{Exp}(\lambda)$:** $M_X(t) = \frac{\lambda}{\lambda-t}$ for $t ### Moment Inequalities - Provide bounds on the probability of an RV being far from its mean or very large, especially when the full distribution is unknown. #### Markov's Inequality - For a non-negative RV $X$ with $E|X| 0$: $$P(X \ge c) \le \frac{E(X)}{c}$$ #### Chebyshev's Inequality - For an RV $X$ with $E(X^2) 0$: $$P(|X - \mu| \ge \alpha) \le \frac{\sigma^2}{\alpha^2}$$ - This inequality generally provides a more accurate estimation than Markov's inequality, as it uses both mean and variance.