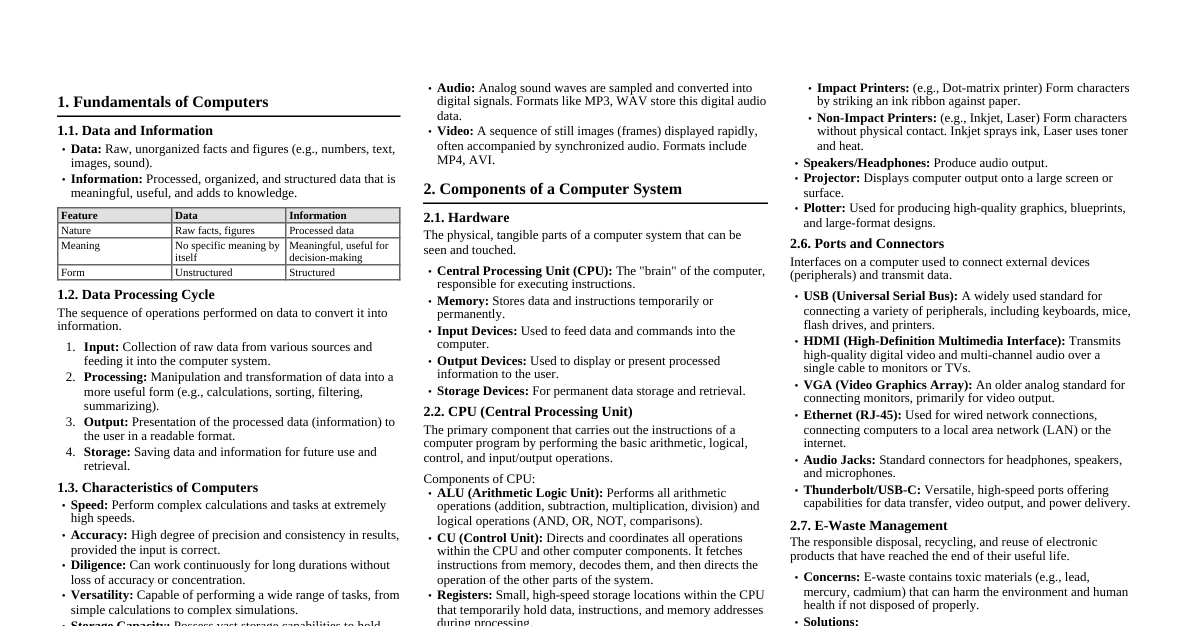

1. Consumer Equilibrium: Utility Maximization This is the most fundamental application. Indifference curves, combined with a budget constraint, determine the optimal consumption bundle for a consumer. The consumer aims to reach the highest possible indifference curve given their limited income and market prices. Mechanism: The point where the budget line is tangent to an indifference curve represents the consumer's equilibrium. At this point, the slope of the indifference curve (Marginal Rate of Substitution, MRS) equals the slope of the budget line (price ratio). Mathematical Condition: $MRS_{xy} = P_x / P_y$. This means the rate at which the consumer is willing to trade good X for good Y is exactly equal to the rate at which they can trade them in the market. Significance: Explains how rational consumers allocate their income among different goods and services to maximize their satisfaction. 2. Income and Substitution Effects of Price Changes When the price of a good changes, its effect on consumption can be decomposed into two parts: the substitution effect and the income effect. Indifference curves are crucial for this decomposition. Substitution Effect: This effect captures the change in consumption due to a change in the relative prices of goods, holding the consumer's utility constant. Graphically, it's a movement along the initial indifference curve to a point where the MRS equals the new price ratio. It always leads to consuming less of the relatively more expensive good. Income Effect: This effect captures the change in consumption due to a change in the consumer's real purchasing power, holding relative prices constant. Graphically, it's a parallel shift of the budget line to the new indifference curve. For Normal Goods : Income effect is positive (consume more as real income rises). For Inferior Goods : Income effect is negative (consume less as real income rises). For Giffen Goods : A special type of inferior good where the negative income effect is so strong that it outweighs the positive substitution effect, leading to an upward-sloping demand curve. Total Price Effect: The sum of the substitution effect and the income effect. 3. Labor-Leisure Choice Indifference curves can model an individual's decision between working (to earn income for consumption) and enjoying leisure. This helps explain labor supply decisions. Indifference Curves: Show trade-offs between leisure time (e.g., hours per day) and income (which can be used for consumption). Budget Constraint: Represents the maximum income an individual can earn by giving up leisure hours, given the prevailing wage rate ($w$). The slope of the budget line is $-w$. Equilibrium: The tangency point where the MRS between leisure and income equals the wage rate ($MRS_{Leisure, Income} = w$). This is where the individual maximizes their utility. Applications: Analyzing the impact of wage changes on hours worked (e.g., the backward-bending labor supply curve), effects of taxes on labor supply, or government welfare programs. 4. Intertemporal Consumption Choice (Saving and Borrowing) This application uses indifference curves to analyze how individuals allocate consumption across different time periods (e.g., present vs. future), which underlies saving and borrowing decisions. Indifference Curves: Represent preferences for consumption in the current period ($C_1$) versus consumption in a future period ($C_2$). The slope reflects the individual's marginal rate of time preference. Budget Constraint: The intertemporal budget line shows the feasible combinations of current and future consumption, considering current income ($Y_1$), future income ($Y_2$), and the market interest rate ($r$). Its slope is $-(1+r)$, reflecting the trade-off: giving up \$1 today allows you to consume $\$(1+r)$ in the future. Equilibrium: The tangency point where $MRS_{C_1, C_2} = 1+r$. This determines the optimal saving or borrowing amount. Applications: Understanding factors influencing saving rates, the impact of interest rate changes on consumption patterns, and government fiscal policies. 5. Exchange Economy (Edgeworth Box) The Edgeworth Box diagram uses indifference curves to illustrate the potential for mutual gains from trade between two individuals and to identify efficient allocations of goods. Construction: A rectangular box where the width represents the total amount of one good and the height represents the total amount of another good available in the economy. Each corner serves as an origin for one individual's indifference map. Indifference Curves: Each person's indifference curves are drawn from their respective origin. Contract Curve: The locus of all points where the indifference curves of the two individuals are tangent to each other. At these points, their MRS values are equal ($MRS_A = MRS_B$), meaning no further mutually beneficial trades are possible without making one person worse off. These are Pareto efficient allocations. Core: The segment of the contract curve that represents allocations preferred by both individuals to their initial endowment (starting point). Significance: Demonstrates the concept of Pareto efficiency, the benefits of voluntary exchange, and the determination of equilibrium in a simple exchange economy. 6. Risk and Uncertainty (Expected Utility Theory) While more complex, indifference curves can be adapted to model choices under uncertainty, particularly in expected utility theory. Indifference Curves: Can be drawn in a state-contingent consumption space (e.g., consumption if "good state" occurs vs. consumption if "bad state" occurs). The shape reveals the individual's attitude towards risk (risk-averse, risk-neutral, risk-loving). Budget Line: Represents the feasible combinations of consumption in different states of the world, given probabilities and prices of contingent claims (e.g., insurance premiums). Applications: Explaining decisions like buying insurance, portfolio selection (choosing between risky and safe assets), and investment choices. Important Facts about Indifference Curves Feature Description Implication Downward Sloping To maintain the same level of satisfaction, if the amount of one good decreases, the amount of the other good must increase. Assumes "more is better" (non-satiation). Convex to the Origin The MRS diminishes as one moves down the curve. Consumers are willing to give up less of good Y for an additional unit of good X as they consume more of X. Reflects the law of diminishing marginal rate of substitution. Never Intersect If two indifference curves intersected, it would imply that a single consumption bundle yields two different levels of satisfaction, which is contradictory. Ensures consistency and transitivity of preferences. Higher Curves = Higher Utility An indifference curve further away from the origin represents a higher level of total satisfaction. More goods generally lead to more utility. Complete & Transitive Consumers can compare and rank all possible bundles (completeness), and their preferences are consistent (transitivity). Fundamental assumptions for rational consumer behavior.