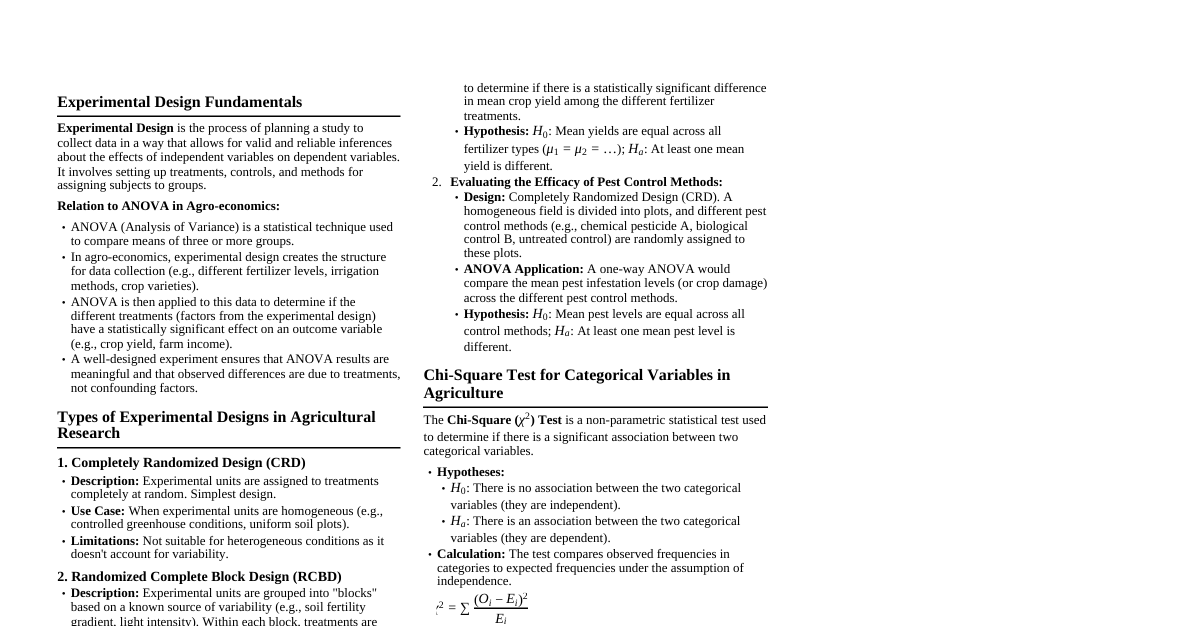

CPU Performance Factors Instruction Count: Determined by ISA and compiler. CPI (Cycles Per Instruction) & Cycle Time: Determined by CPU hardware. We examine two RISC-V implementations: a simplified version and a pipelined version. Simple RISC-V Subset: Memory reference: ld , sd Arithmetic/logical: add , sub , and , or Control transfer: beq Instruction Execution Phases PC $\rightarrow$ Instruction Memory: Fetch instruction. Register Numbers $\rightarrow$ Register File: Read registers. ALU Calculation (depending on instruction class): Arithmetic result Memory address for load/store Branch comparison Access Data Memory: For load/store. PC Update: PC $\leftarrow$ target address or PC + 4. Logic Design Basics Information Encoding: Binary (low voltage = 0, high voltage = 1). Data Representation: One wire per bit, multi-bit data on multi-wire buses. Combinational Element: Operates on data. Output is a function of input. State (Sequential) Elements: Store information. Combinational Elements Examples AND-gate: $Y = A \ \& \ B$ Adder: $Y = A + B$ Multiplexer: $Y = S \ ? \ I_1 : I_0$ Arithmetic/Logic Unit (ALU): $Y = F(A, B)$ Sequential Elements (Registers) Stores data in a circuit. Uses a clock signal to determine when to update the stored value. Edge-triggered: Updates when Clock changes from 0 to 1. With Write Control: Only updates on clock edge when write control input is 1. Used when stored value is required later. Clocking Methodology Combinational logic transforms data during clock cycles. Data transformation occurs between clock edges. Input from state elements, output to state elements. Longest delay in any path determines the clock period. Building a Datapath Datapath: Elements that process data and addresses in the CPU (Registers, ALUs, Muxes, Memories). We build a RISC-V datapath incrementally, refining the overview design. Instruction Fetch PC provides the address to Instruction Memory. Instruction Memory outputs the instruction. PC is incremented by 4 for the next instruction (for 64-bit registers). R-Format Instructions Read two register operands. Perform arithmetic/logical operation in ALU. Write register result back to register file. Load/Store Instructions Read register operands. Calculate address using 12-bit offset (sign-extended), using ALU (addition). Load: Read from data memory and update a register. Store: Write a register's value to data memory. Branch Instructions Read register operands. Compare operands using ALU (subtract and check Zero output). Calculate target address: Sign-extend displacement. Shift displacement left by 1 (for halfword displacement, effectively multiplying by 2). Add to PC value. Composing the Elements for a Single-Cycle Datapath First-cut datapath executes an instruction in one clock cycle. Each datapath element can only perform one function at a time. Requires separate instruction and data memories. Multiplexers are used where alternate data sources are needed for different instructions. ALU Control ALU functionality is determined by instruction type: Load/Store: $F = \text{add}$ Branch: $F = \text{subtract}$ (for comparison) R-type: $F$ depends on the opcode/funct fields. 2-bit ALUOp is derived from the instruction's opcode. Combinational logic derives the final ALU control signal. opcode ALUOp Operation ALU function ALU control ld 00 load register add 0010 sd 00 store register add 0010 beq 01 branch on equal subtract 0110 R-type 10 add add 0010 subtract subtract 0110 AND AND 0000 OR OR 0001 Performance Issues (Single-Cycle Datapath) Longest delay determines the clock period (e.g., load instruction: Instruction memory $\rightarrow$ Register file $\rightarrow$ ALU $\rightarrow$ Data memory $\rightarrow$ Register file). Not feasible to vary clock period for different instructions. Violates the design principle: "Making the common case fast." Performance is improved by pipelining. Pipelining Analogy Overlapping execution of multiple instructions (like laundry stages). Parallelism improves performance (throughput). RISC-V Pipeline Stages IF (Instruction Fetch): Fetch instruction from memory. ID (Instruction Decode): Decode instruction & read registers. EX (Execute): Execute operation or calculate address. MEM (Memory Access): Access memory operand (load/store). WB (Write Back): Write result back to register. Pipeline Performance Comparison Assumed Stage Times: Register read or write: 100ps Other stages: 200ps Instr Instr fetch Register read ALU op Memory access Register write Total time (Single-Cycle) ld 200ps 100 ps 200ps 200ps 100 ps 800ps sd 200ps 100 ps 200ps 200ps 700ps R-format 200ps 100 ps 200ps 100 ps 600ps beq 200ps 100 ps 200ps 500ps Single-Cycle $T_c$: 800ps (determined by longest stage). Pipelined $T_c$: 200ps (determined by the longest individual stage, assuming ideal pipelining). Pipelining and ISA Design RISC-V ISA designed for pipelining: All instructions are 32-bits: Easier to fetch and decode in one cycle (unlike x86's variable-length instructions). Few and regular instruction formats: Can decode and read registers in one step. Load/store addressing: Address can be calculated in the 3rd (EX) stage, memory accessed in the 4th (MEM) stage. Hazards in Pipelining Situations that prevent starting the next instruction in the next cycle. Structural Hazards: A required resource is busy. Conflict for use of a resource (e.g., single memory for instruction fetch and data access). In RISC-V, load/store requires data access, instruction fetch requires instruction access. Pipelined datapaths require separate instruction/data memories (or caches) to avoid stalls. Data Hazards: Need to wait for a previous instruction to complete its data read/write. An instruction depends on the completion of data access by a previous instruction. Example: add x19, x0, x1 followed by sub x2, x19, x3 . sub needs x19 from add . Control Hazards: Deciding on control action depends on a previous instruction (e.g., branch outcome). Forwarding (aka Bypassing) to Resolve Data Hazards Use the result as soon as it is computed, rather than waiting for it to be stored in a register. Requires extra connections in the datapath to forward results from EX/MEM stages to earlier stages. Load-Use Data Hazard Sometimes forwarding isn't enough; can't forward backward in time. If a value is not yet computed when needed by the very next instruction, a stall (bubble) is required. Example: ld x1, 0(x2) followed by sub x4, x1, x5 . sub needs x1 from memory, which is only available after the MEM stage of ld . Code Scheduling to Avoid Stalls Reorder code to avoid using a load result in the immediately following instruction. This allows other independent instructions to execute while the load completes, reducing stalls. Example: Reordering instructions can reduce cycles (e.g., from 13 cycles to 11 cycles). Stall on Branch (Control Hazard) Wait until the branch outcome is determined before fetching the next instruction. This introduces bubbles into the pipeline until the target address is known. Pipeline Registers Registers placed between pipeline stages (e.g., IF/ID, ID/EX, EX/MEM, MEM/WB). Hold information produced in the previous stage for use by the next stage. Pipeline Summary Pipelining improves performance by increasing instruction throughput. Executes multiple instructions in parallel. Each instruction still has the same latency (time to complete from start to finish). Subject to hazards: structural, data, control. Instruction set design significantly affects the complexity of pipeline implementation.