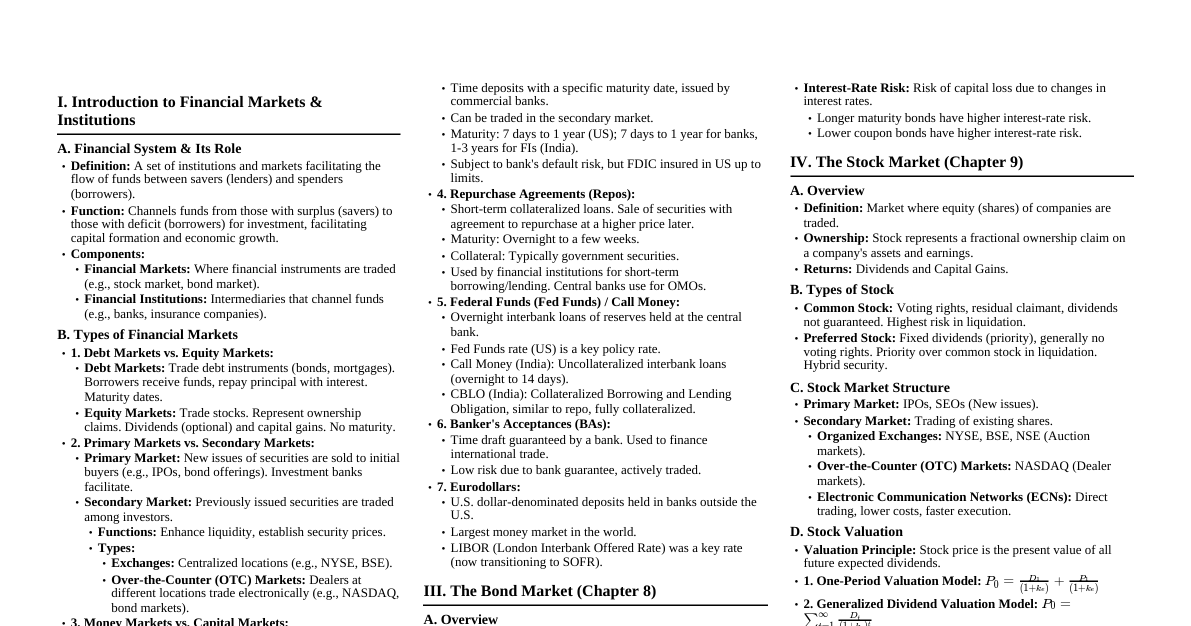

Money Markets (Chapter 7) Definition: Financial markets for short-term debt instruments (maturity less than one year). These instruments are highly liquid, low risk, and typically have large denominations. Functions: Facilitates efficient short-term borrowing and lending for governments, corporations, and financial institutions. Provides liquidity to participants, allowing them to manage short-term cash flows. Serves as a crucial channel for the implementation of monetary policy by the central bank. Allows for price discovery for short-term interest rates. Characteristics: Wholesale Market: Transactions are typically very large, involving institutional investors. Low Default Risk: Instruments are generally issued by highly creditworthy entities. High Liquidity: Active secondary markets allow for easy conversion to cash. Low Transaction Costs: Due to large denominations and electronic trading. Key Instruments: Treasury Bills (T-bills): Short-term debt issued by the government, typically 91, 182, or 364 days. Issued at a discount to face value, with no explicit interest payments. Considered virtually risk-free. Calculation of return: Investment Yield: $i_{investment} = \frac{F-P}{P} \times \frac{365}{n}$ Discount Yield: $i_{discount} = \frac{F-P}{F} \times \frac{360}{n}$ Commercial Paper (CP): Unsecured promissory notes issued by large, creditworthy corporations to finance short-term working capital needs. Maturity from 7 days to 1 year. Issued at a discount. Attractive due to lower interest rates than bank loans for highly rated firms. Certificates of Deposit (CDs): Time deposits with a specific maturity date and interest rate, issued by banks. Negotiable CDs can be traded in the secondary market before maturity. Important source of funds for banks. Repurchase Agreements (Repos): Short-term collateralized loans, typically overnight. One party sells securities (e.g., T-bills) to another with an agreement to repurchase them at a slightly higher price on a specified future date. Used by banks and dealers to manage short-term liquidity and by the central bank for OMOs. Federal Funds (Fed Funds): Overnight loans between banks in the US (similar to Call Money in India). Unsecured loans of excess reserves held at the central bank. Fed Funds rate is a key target for monetary policy. Banker's Acceptances: Time drafts issued by a firm, accepted by a bank, and guaranteed for payment. Primarily used to finance international trade. Highly liquid and can be traded in the secondary market. Eurodollars: U.S. dollar-denominated deposits held in banks outside the United States. LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) is a key reference rate for Eurodollar deposits and other financial instruments. The Bond Market (Chapter 8) Definition: Market for long-term debt instruments (maturity generally greater than one year). Also known as the capital market for debt. Purpose: Facilitates long-term borrowing for governments and corporations to finance capital expenditures and projects. Key Characteristics: Par Value (Face Value): The principal amount of the bond that is repaid at maturity. Coupon Rate: The stated annual interest rate paid on the par value. Coupon payments are typically made semi-annually. Maturity Date: The date on which the principal amount is repaid. Yield to Maturity (YTM): The total return anticipated on a bond if it is held until it matures. It is the discount rate that equates the present value of all future cash flows (coupons and par value) to the bond's current market price. Types of Bonds: Government Bonds: Treasury Bonds/Notes (G-Secs in India): Issued by the central government. Considered to have very low (or zero) default risk. State and Local Government Bonds (SDLs in India, Municipal Bonds in US): Issued by state and local governments. Can offer tax advantages to investors. Corporate Bonds: Issued by corporations to raise long-term capital. Carry higher default risk than government bonds, reflected in higher yields. Can be secured (backed by specific assets) or unsecured (debentures). Often include provisions like call options (issuer can repurchase) or put options (holder can sell back). Convertible bonds allow conversion into common stock. Bond Valuation: The price of a bond is the present value of its future cash flows (coupon payments and face value). $P = \sum_{t=1}^{n} \frac{C}{(1+i)^t} + \frac{F}{(1+i)^n}$ $P$: Current bond price $C$: Annual coupon payment $F$: Face (par) value $i$: Yield to maturity (YTM) $n$: Number of years to maturity Inverse Relationship: Bond prices and interest rates (YTM) move in opposite directions. When interest rates rise, bond prices fall, and vice versa. Current Yield: $\text{Current Yield} = \frac{\text{Annual Coupon Payment}}{\text{Current Market Price}}$. Discount Bond: Sells below face value (YTM > Coupon Rate). Premium Bond: Sells above face value (YTM Par Bond: Sells at face value (YTM = Coupon Rate). Interest-Rate Risk: The risk that changes in market interest rates will affect the value of a bond portfolio. Longer maturity bonds and bonds with lower coupon rates are more sensitive to interest rate changes (higher interest-rate risk). Inflation Risk: The risk that inflation will erode the purchasing power of a bond's future cash flows. The Stock Market (Chapter 9) Definition: Market for equity securities, representing ownership stakes in corporations. Purpose: Allows corporations to raise equity capital for long-term investment. Provides investors with a claim on future earnings and assets, and potential for capital appreciation. Offers liquidity for investors to buy and sell ownership stakes. Types of Stock: Common Stock: Represents residual ownership. Grants voting rights (usually one vote per share) on corporate matters. Dividends are variable and not guaranteed. Has a residual claim on assets in liquidation (after creditors and preferred stockholders are paid). Potential for significant capital gains. Preferred Stock: Typically has no voting rights. Pays a fixed dividend, similar to a bond. Has priority over common stock in dividend payments and asset claims during liquidation. Often considered a hybrid security, having characteristics of both debt and equity. Stock Market Trading: Primary Market: New issues of stock are sold to the public for the first time (e.g., Initial Public Offerings - IPOs). Secondary Market: Existing shares are traded among investors. Organized Exchanges (e.g., NYSE, BSE, NSE): Physical or electronic marketplaces with strict rules and listing requirements. Operate as auction markets. Over-the-Counter (OTC) Markets (e.g., NASDAQ): Decentralized networks where trades are conducted directly between dealers via electronic communication. Electronic Communication Networks (ECNs): Automated trading systems that match buy and sell orders directly, offering speed, anonymity, and lower costs. Stock Valuation: The price of a stock is the present value of its expected future cash flows (dividends and future selling price). One-Period Valuation Model: $P_0 = \frac{D_1}{(1+k_e)} + \frac{P_1}{(1+k_e)}$ Generalized Dividend Valuation Model: $P_0 = \sum_{t=1}^{\infty} \frac{D_t}{(1+k_e)^t}$ Gordon Growth Model (Dividend Discount Model - DDM): Assumes constant dividend growth. $P_0 = \frac{D_0(1+g)}{(k_e-g)} = \frac{D_1}{(k_e-g)}$ $P_0$: Current stock price $D_0$: Most recent dividend paid $D_1$: Expected dividend next period $k_e$: Required rate of return on equity $g$: Constant growth rate of dividends ($g Price-Earnings (P/E) Ratio: A common valuation metric. $P/E = \frac{\text{Current Stock Price}}{\text{Earnings Per Share}}$. Higher P/E often indicates higher growth expectations or lower perceived risk. Stock Market Indexes: Composite values that track the performance of a basket of stocks (e.g., Dow Jones Industrial Average, S&P 500, S&P BSE SENSEX). Used as benchmarks for market performance. Regulation: Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) in India; Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the US. Aims to protect investors, ensure fair and orderly markets, and promote transparency. Foreign Exchange Market (Chapter 10) Definition: The global marketplace where currencies are traded. It is the largest and most liquid financial market in the world. Exchange Rate: The price of one country's currency in terms of another country's currency. Types of Transactions: Spot Transactions: Involve the immediate (typically within two business days) exchange of currencies at the current spot exchange rate. Forward Transactions: Involve the agreement to exchange currencies at a specified future date (e.g., 30, 90, 180 days) at a pre-agreed forward exchange rate. Used for hedging. Appreciation vs. Depreciation: Appreciation: When a currency increases in value relative to another currency. Depreciation: When a currency decreases in value relative to another currency. Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Law of One Price: In competitive markets free of transportation costs and trade barriers, identical goods sold in different countries must sell for the same price when expressed in terms of the same currency. Purchasing Power Parity (PPP): States that exchange rates between currencies are in equilibrium when their purchasing power is the same in each of the two countries. This implies that the exchange rate adjusts to reflect changes in price levels (inflation). Works well for the long run and for countries with high inflation differentials, but not perfectly in the short run due to trade barriers and non-tradable goods. Factors Affecting Long-Run Exchange Rates: Relative Price Levels: A rise in a country's price level relative to another country's causes its currency to depreciate. Tariffs and Quotas: Increased trade barriers cause a country's currency to appreciate. Preferences for Domestic Goods: Increased demand for a country's exports causes its currency to appreciate. Productivity: Higher relative productivity growth in a country causes its currency to appreciate. Exchange Rates in the Short Run (Asset Market Approach): Exchange rates are determined by the supply and demand for domestic and foreign assets (primarily bank deposits and bonds). Key Determinants: Relative Interest Rates: An increase in a country's domestic interest rate (relative to foreign interest rates) makes domestic deposits more attractive, leading to an appreciation of the domestic currency. Expected Future Exchange Rates: If investors expect a currency to appreciate in the future, demand for that currency's assets increases, leading to an immediate appreciation. Interest Rate Parity Condition: States that the expected return on domestic assets must equal the expected return on foreign assets (adjusted for expected exchange rate changes). Exchange Rate Overshooting: Occurs when the immediate response of the exchange rate to a change in monetary policy (e.g., interest rate change) is larger than its long-run response. This explains why exchange rates are so volatile. Why Do Interest Rates Change? (Chapter 12) Determinants of Asset Demand: Investors decide which assets to hold based on four primary factors: Wealth: An increase in wealth generally increases the demand for all assets. Expected Return ($R_e$): An increase in an asset's expected return (relative to alternative assets) increases its demand. Risk ($\sigma$): An increase in an asset's risk (relative to alternative assets) decreases its demand. Liquidity: An increase in an asset's liquidity (relative to alternative assets) increases its demand. Supply and Demand in the Bond Market (Loanable Funds Framework): Demand Curve for Bonds ($B_d$): Slopes downward. As the bond price falls (interest rate rises), the expected return on bonds (relative to other assets) increases, so the quantity of bonds demanded rises. Supply Curve for Bonds ($B_s$): Slopes upward. As the bond price falls (interest rate rises), the cost of borrowing increases, so the quantity of bonds supplied falls. Equilibrium: Occurs where $B_d = B_s$, determining the equilibrium bond price and thus the equilibrium interest rate. Inverse Relationship: Bond prices and interest rates are inversely related. Factors Shifting the Demand Curve for Bonds: Wealth: $\uparrow$ Wealth $\rightarrow B_d \uparrow$. Expected Returns on Bonds: $\downarrow$ Expected future interest rates $\rightarrow \uparrow$ Expected return on long-term bonds $\rightarrow B_d \uparrow$. $\uparrow$ Expected inflation ($p^e$) $\rightarrow \downarrow$ Real expected return on bonds $\rightarrow B_d \downarrow$. Risk: $\downarrow$ Risk of bonds (e.g., less default risk) $\rightarrow B_d \uparrow$. $\uparrow$ Risk of alternative assets (e.g., stocks) $\rightarrow B_d \uparrow$. Liquidity: $\uparrow$ Liquidity of bonds $\rightarrow B_d \uparrow$. $\downarrow$ Liquidity of alternative assets $\rightarrow B_d \uparrow$. Factors Shifting the Supply Curve for Bonds: Profitability of Investment Opportunities: $\uparrow$ Profitable investment opportunities (e.g., during economic expansion) $\rightarrow B_s \uparrow$. Expected Inflation ($p^e$): $\uparrow p^e \rightarrow$ Real cost of borrowing falls $\rightarrow B_s \uparrow$. Government Activities: $\uparrow$ Government budget deficits $\rightarrow \uparrow$ Government borrowing $\rightarrow B_s \uparrow$. Changes in Equilibrium Interest Rates: Fisher Effect: An increase in expected inflation leads to an increase in nominal interest rates. ($\uparrow p^e \rightarrow B_d \downarrow$ and $B_s \uparrow \rightarrow P \downarrow, i \uparrow$). Business Cycle Expansion: Typically leads to an increase in interest rates as both bond demand (due to increased wealth) and bond supply (due to increased investment opportunities) shift right, with supply often shifting more. Why Do Risk and Term Structure Affects Interest Rates? (Chapter 13) Risk Structure of Interest Rates: Explains why bonds with the same maturity but different characteristics (risk, liquidity, tax treatment) have different interest rates. Factors Affecting Risk Structure: Default Risk: The risk that the issuer of the bond will be unable or unwilling to make interest payments or repay the principal. Bonds with higher default risk must offer a higher interest rate to compensate investors. Risk Premium: The spread between the interest rate on a bond with default risk and the interest rate on a default-free bond (e.g., U.S. Treasury bonds). Credit rating agencies (e.g., Moody's, S&P, Fitch) assess default risk. Liquidity: The ease and speed with which an asset can be converted into cash without significant loss of value. More liquid bonds (e.g., Treasury bonds) are more desirable, so they require lower interest rates. Less liquid bonds (e.g., corporate bonds) must offer higher rates. Income Tax Considerations: Interest income from some bonds (e.g., municipal bonds in the US) is exempt from federal and/or state income taxes. This tax-exempt status makes them more attractive to high-income earners, allowing them to offer lower yields compared to taxable bonds of similar risk. Term Structure of Interest Rates: Explains why bonds with the same risk, liquidity, and tax characteristics but different maturities have different interest rates. This relationship is depicted by the yield curve. Facts the Term Structure Theories Must Explain: Interest rates on bonds of different maturities tend to move together over time. When short-term interest rates are low, the yield curve is more likely to be upward-sloping; when short-term rates are high, the yield curve is more likely to be inverted (downward-sloping). The yield curve is typically upward-sloping. Theories of Term Structure: Expectations Theory: Assumption: Bonds of different maturities are perfect substitutes. Implication: The interest rate on a long-term bond is the average of the short-term interest rates that are expected to occur over the life of the long-term bond. Explains facts 1 and 2 well. Fails to explain fact 3 (why yield curves are typically upward-sloping), as it implies an average expected future short rate would be higher than current short rate. Market Segmentation Theory: Assumption: Bonds of different maturities are not substitutes at all. Investors have strong preferences for bonds of one maturity over another. Implication: The interest rate for each bond maturity is determined independently by the supply and demand for bonds of that specific maturity. Can explain fact 3 (if demand for short-term bonds is higher than long-term). Fails to explain facts 1 and 2, as it suggests no relationship between rates of different maturities. Liquidity Premium Theory (Preferred Habitat Theory): Assumption: Bonds of different maturities are substitutes, but not perfect substitutes. Investors prefer short-term bonds due to their lower interest-rate risk. Implication: The interest rate on a long-term bond equals the average of the short-term interest rates expected to occur over the life of the long-term bond, plus a liquidity (or term) premium that rises with maturity. Long-term rate = (Average of expected future short rates) + Liquidity Premium. Successfully explains all three empirical facts about the term structure. Commercial Banking (Chapter 14) Definition: Financial institutions that accept deposits from the public and provide loans for various purposes. They are profit-oriented organizations. Key Functions: Primary Functions: Accepting Deposits: Demand Deposits (Current Accounts): Payable on demand, no interest or low interest, suitable for businesses. Savings Deposits: Interest-bearing, limited withdrawals, encourages saving. Time Deposits (Fixed Deposits, Recurring Deposits): Fixed maturity, higher interest rates, no withdrawals before maturity without penalty. Advancing Loans: Cash Credit: Short-term finance against collateral (inventory, receivables). Overdraft: Permission to overdraw from a current account up to a limit. Term Loans: Loans for a fixed period (medium to long-term) for capital expenditures. Discounting Bills of Exchange: Purchasing trade bills before maturity. Secondary Functions: Agency Services: Collection of cheques, bills, dividends; payment of insurance premiums, taxes; fund transfers (NEFT, RTGS, IMPS); acting as executor/trustee. General Utility Services: Locker facilities, issuance of traveler's cheques, letters of credit, underwriting securities, foreign exchange services, merchant banking. Credit Creation: The most unique function of commercial banks. Banks create money by making loans. When a bank makes a loan, it credits the borrower's account, creating a new deposit. This new deposit is then spent, and a portion may be redeposited in another bank, leading to a multiplier effect. Credit Multiplier ($k$): The amount of money the banking system generates with each dollar of reserves. $k = \frac{1}{\text{Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR)}}$. Change in Deposits ($\Delta D$) = $k \times \text{Initial Excess Reserves}$. Assumptions for maximum credit creation: All loans are redeposited, no cash drain, banks hold no excess reserves. Limitations: Affected by CRR, public's demand for currency, availability of suitable borrowers, overall economic conditions, and monetary policy of the central bank. Role in Economic Development: Capital formation, mobilization of savings, provision of credit to various sectors (agriculture, industry, trade), entrepreneurial development, promoting financial inclusion, facilitating payment systems. Structure of Banking (India): Public Sector Banks, Private Sector Banks (old and new), Foreign Banks, Regional Rural Banks (RRBs), Cooperative Banks. Central Banking (Chapter 15) Definition: The apex financial institution of a country that regulates the monetary and banking system, controls money supply, and manages foreign exchange reserves. (e.g., Reserve Bank of India - RBI, Federal Reserve - Fed). Key Functions: Monopoly of Note Issue: Sole authority to issue currency, ensuring uniformity and public confidence. Banker, Agent, and Advisor to the Government: Manages government accounts, facilitates government borrowing, advises on financial policies. Banker's Bank: Holds deposits of commercial banks, provides loans, and acts as a clearing house for interbank transactions. Lender of Last Resort: Provides liquidity to commercial banks during financial crises to prevent systemic collapse. Custodian of Foreign Exchange Reserves: Manages the country's foreign currency assets and gold reserves, maintaining exchange rate stability. Controller of Credit (Monetary Policy): Regulates the quantity, cost, and direction of credit in the economy to achieve macroeconomic objectives. Developmental Role: Promotes financial sector development, financial inclusion, and overall economic growth. Objectives of Monetary Policy: Price stability, full employment, economic growth, exchange rate stability, financial system stability. Instruments of Credit Control: Quantitative (General) Methods: Affect the overall volume of credit. Bank Rate (Repo Rate in India): The rate at which the central bank lends money to commercial banks against approved securities. $\uparrow$ Bank Rate $\rightarrow$ cost of borrowing for banks $\uparrow \rightarrow$ banks lend at higher rates $\rightarrow \downarrow$ credit. Open Market Operations (OMOs): Buying and selling of government securities in the open market. Buying securities $\rightarrow$ injects liquidity into the banking system $\rightarrow \uparrow$ bank reserves $\rightarrow \uparrow$ credit. Selling securities $\rightarrow$ drains liquidity $\rightarrow \downarrow$ bank reserves $\rightarrow \downarrow$ credit. Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR): The percentage of a bank's net demand and time liabilities that it must hold as reserves with the central bank. $\uparrow$ CRR $\rightarrow \downarrow$ funds available for lending $\rightarrow \downarrow$ credit. Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR): The percentage of a bank's net demand and time liabilities that it must maintain in liquid assets (cash, gold, approved securities). $\uparrow$ SLR $\rightarrow \downarrow$ funds for lending $\rightarrow \downarrow$ credit. Qualitative (Selective) Methods: Control the direction or purpose of credit. Margin Requirements: The percentage of a loan that cannot be covered by the borrowed funds (e.g., for loans against securities). $\uparrow$ Margin $\rightarrow \downarrow$ credit for speculative activities. Regulation of Consumer Credit: Controlling hire-purchase terms, down payments, etc. Rationing of Credit: Limiting the amount of credit available to certain sectors or banks. Moral Suasion: Persuading banks through advice, suggestions, or warnings to follow central bank policy. Direct Action: Imposing penalties on banks that do not follow central bank directives. Financial Reform (Chapter 16) Nationalization of Banks (Indian context): Background: 14 major private banks nationalized in 1969, followed by 6 more in 1980. Objectives: Social control over credit allocation to align with national planning priorities. Channel credit to priority sectors (agriculture, small-scale industries) neglected by private banks. Promote financial inclusion and extend banking services to rural and unbanked areas. Ensure stability of the banking system and protect depositors' interests. Reduce concentration of economic power. Achievements: Significant branch expansion, massive deposit mobilization, substantial credit flow to agriculture and small industries, enhanced public confidence. Criticisms: Decline in efficiency and profitability due to bureaucracy and lack of competition. Increase in Non-Performing Assets (NPAs) due to directed lending and political interference. Lack of innovation and customer service. Financial Sector Reforms (Post-1991 in India - Narasimham Committee Reports): Context: Initiated as part of broader economic liberalization following the 1991 economic crisis. Aimed at making the financial sector more efficient, competitive, and robust. Key Objectives: Liberalization: Reduce government control and introduce market-based mechanisms. Globalization: Integrate Indian financial markets with global markets. Modernization: Adopt new technologies and financial products. Strengthening: Improve prudential norms and regulatory framework to ensure stability. Major Reform Measures: Interest Rate Deregulation: Phased deregulation of lending and deposit rates, allowing banks to determine rates based on market forces. Reduction in SLR and CRR: Gradual reduction of statutory requirements to release more funds for commercial lending. Prudential Norms: Introduction of international best practices for income recognition, asset classification (NPA definition), and provisioning for bad debts. Capital Adequacy Norms: Implementation of Basel norms (Basel I, II, III) requiring banks to maintain minimum capital against risk-weighted assets. Entry of New Private Sector Banks: Allowing new private banks to increase competition and efficiency. Strengthening Regulatory and Supervisory Framework: Empowering RBI and SEBI, improving supervision of financial institutions. Debt Recovery Mechanisms: Establishment of Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) and Assets Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) to tackle NPAs. Introduction of New Financial Instruments: Derivatives, mutual funds, etc. Impact: Increased competition, improved efficiency, greater product innovation, enhanced financial stability, better risk management. However, challenges like managing NPAs and ensuring financial inclusion persist. Hedging with Financial Derivatives (Chapter 24) Hedging: A strategy designed to reduce or offset the risk of adverse price movements in an asset. It involves taking an offsetting position in a related security. Financial Derivatives: Financial instruments whose value is derived from the value of an underlying asset (e.g., stocks, bonds, currencies, commodities, interest rates, indices). Key Concepts: Long Position: Holding an asset or an obligation to buy an asset. Short Position: Selling an asset that one does not own (borrowing it) with the expectation of buying it back at a lower price, or an obligation to sell an asset. Types of Financial Derivatives for Hedging: Forward Contracts: An agreement between two parties to buy or sell an asset at a specified price on a future date. Characteristics: Over-the-counter (OTC), customizable, illiquid, subject to default risk. Hedging Use: Locks in a future price or exchange rate, eliminating price uncertainty (e.g., a company expecting a foreign currency payment can sell a forward contract to lock in the exchange rate). Futures Contracts: Standardized forward contracts traded on organized exchanges. Characteristics: Standardized terms, highly liquid, marked-to-market daily (minimizes default risk), guaranteed by a clearing house. Hedging Use: Similar to forwards but with greater liquidity and reduced counterparty risk. Used to hedge interest rate risk (e.g., bond futures), currency risk, commodity price risk, or stock market risk (e.g., stock index futures). Micro-hedge: Hedging a specific asset. Macro-hedge: Hedging the overall risk of a portfolio or firm. Options: A contract that gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an underlying asset at a specified price (strike price) on or before a specified date (expiration date). Call Option: Gives the holder the right to buy the underlying asset. Used to hedge against rising prices of an asset to be purchased. Put Option: Gives the holder the right to sell the underlying asset. Used to hedge against falling prices of an asset that is owned. Premium: The price paid by the buyer of the option to the seller. Hedging Use: Provides downside protection while retaining upside potential (for a fee - the premium). Interest-Rate Swaps: An agreement between two parties to exchange future interest payments over a specified period. Plain Vanilla Swap: Typically involves exchanging fixed-rate interest payments for floating-rate interest payments (or vice versa) on a notional principal amount. Hedging Use: Allows firms to manage their interest rate exposure (e.g., converting a floating-rate debt into a fixed-rate obligation). Credit Derivatives: Financial contracts that transfer credit risk from one party to another. Credit Default Swap (CDS): The most common type. A buyer makes periodic payments to a seller, and in return, the seller agrees to compensate the buyer if a specified credit event (e.g., default) occurs on a reference asset. Hedging Use: Allows lenders to hedge against the risk of loan defaults. Concerns: While useful for hedging, their complexity and interconnectedness contributed to systemic risk during the 2008 financial crisis.