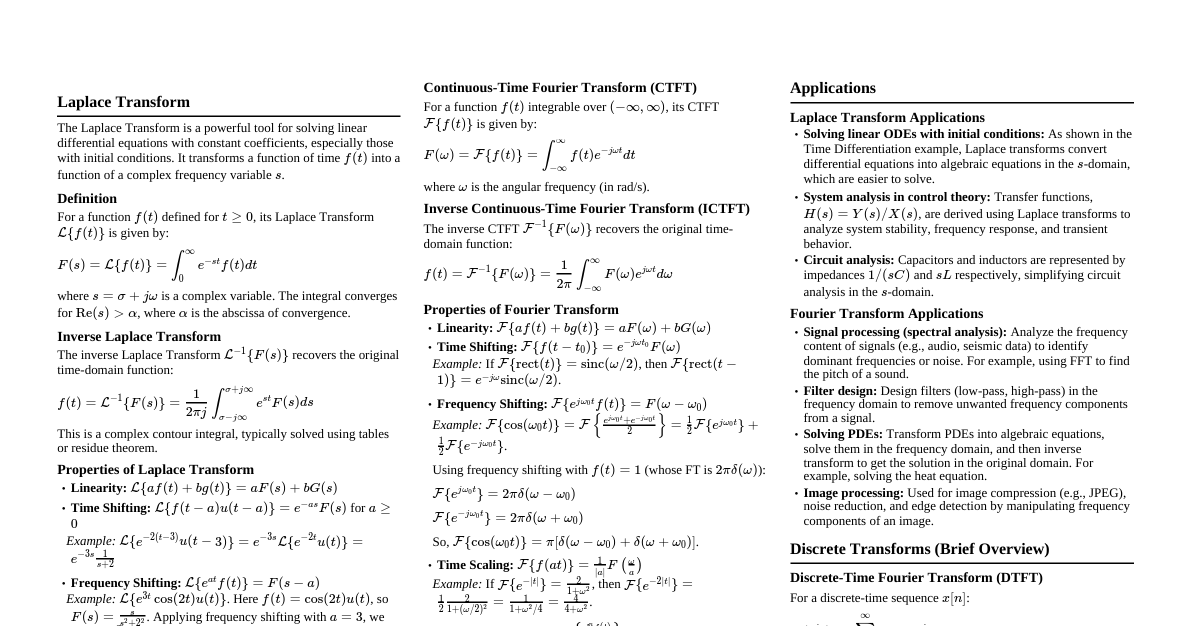

### Definition of Unilateral Laplace Transform The unilateral Laplace Transform of a function $f(t)$ is defined as: $$ F(s) = \mathcal{L}\{f(t)\} = \int_{0^-}^{\infty} f(t)e^{-st} dt $$ where $s = \sigma + j\omega$ is a complex variable, and $0^-$ indicates that the integration starts just before $t=0$ to include any impulses at the origin. The Laplace transform exists if $f(t)$ is piecewise continuous and of exponential order, meaning there exist constants $M$, $k$, and $T$ such that $|f(t)| \le Me^{kt}$ for all $t > T$. The smallest such $k$ is called the abscissa of convergence $\sigma_c$. The region of convergence (ROC) is $\text{Re}\{s\} > \sigma_c$. ### Common Laplace Transform Pairs | $f(t)$, $t \ge 0$ | $F(s) = \mathcal{L}\{f(t)\}$ | ROC | |-------------------|-----------------------------|-----| | $\delta(t)$ | $1$ | All $s$ | | $u(t)$ | $\frac{1}{s}$ | $\text{Re}\{s\} > 0$ | | $t u(t)$ | $\frac{1}{s^2}$ | $\text{Re}\{s\} > 0$ | | $t^n u(t)$ | $\frac{n!}{s^{n+1}}$ | $\text{Re}\{s\} > 0$ | | $e^{-at} u(t)$ | $\frac{1}{s+a}$ | $\text{Re}\{s\} > -a$ | | $t e^{-at} u(t)$ | $\frac{1}{(s+a)^2}$ | $\text{Re}\{s\} > -a$ | | $\sin(\omega_0 t) u(t)$ | $\frac{\omega_0}{s^2 + \omega_0^2}$ | $\text{Re}\{s\} > 0$ | | $\cos(\omega_0 t) u(t)$ | $\frac{s}{s^2 + \omega_0^2}$ | $\text{Re}\{s\} > 0$ | | $e^{-at}\sin(\omega_0 t) u(t)$ | $\frac{\omega_0}{(s+a)^2 + \omega_0^2}$ | $\text{Re}\{s\} > -a$ | | $e^{-at}\cos(\omega_0 t) u(t)$ | $\frac{s+a}{(s+a)^2 + \omega_0^2}$ | $\text{Re}\{s\} > -a$ | ### Properties of Unilateral Laplace Transform - **Linearity:** $\mathcal{L}\{af(t) + bg(t)\} = aF(s) + bG(s)$ - **Time Shifting:** $\mathcal{L}\{f(t-t_0)u(t-t_0)\} = e^{-st_0}F(s)$ for $t_0 \ge 0$ - **Frequency Shifting (Modulation):** $\mathcal{L}\{e^{-at}f(t)\} = F(s+a)$ - **Time Differentiation:** $\mathcal{L}\{\frac{df(t)}{dt}\} = sF(s) - f(0^-)$ - $\mathcal{L}\{\frac{d^2f(t)}{dt^2}\} = s^2F(s) - sf(0^-) - f'(0^-)$ - General: $\mathcal{L}\{f^{(n)}(t)\} = s^nF(s) - \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} s^{n-1-k}f^{(k)}(0^-)$ - **Time Integration:** $\mathcal{L}\{\int_{0^-}^t f(\tau)d\tau\} = \frac{1}{s}F(s)$ - **Multiplication by $t$:** $\mathcal{L}\{tf(t)\} = -\frac{dF(s)}{ds}$ - **Division by $t$:** $\mathcal{L}\{\frac{f(t)}{t}\} = \int_s^{\infty} F(\sigma)d\sigma$ (if $\lim_{t \to 0} \frac{f(t)}{t}$ exists) - **Convolution:** $\mathcal{L}\{f(t) * g(t)\} = F(s)G(s)$ where $f(t) * g(t) = \int_{0^-}^t f(\tau)g(t-\tau)d\tau$ - **Initial Value Theorem:** $\lim_{t \to 0^+} f(t) = \lim_{s \to \infty} sF(s)$ (if the limits exist) - **Final Value Theorem:** $\lim_{t \to \infty} f(t) = \lim_{s \to 0} sF(s)$ (if poles of $sF(s)$ are in LHP) ### Inverse Laplace Transform The inverse Laplace Transform $f(t) = \mathcal{L}^{-1}\{F(s)\}$ is given by the Bromwich integral: $$ f(t) = \frac{1}{2\pi j} \int_{\sigma-j\infty}^{\sigma+j\infty} F(s)e^{st} ds $$ where $\sigma$ is chosen such that the contour lies within the ROC of $F(s)$. In practice, the inverse Laplace transform is usually found using: 1. **Partial Fraction Expansion:** Decompose $F(s)$ into simpler terms whose inverse transforms are known (from the table of common pairs). 2. **Using Properties:** Apply transform properties in reverse. #### Partial Fraction Expansion Steps: 1. **Factor the Denominator:** Express $F(s) = \frac{N(s)}{D(s)}$ where $D(s)$ is factored into linear and irreducible quadratic terms. 2. **Case 1: Distinct Real Roots** $$ F(s) = \frac{A_1}{s-p_1} + \frac{A_2}{s-p_2} + \dots $$ $A_k = \lim_{s \to p_k} (s-p_k)F(s)$ 3. **Case 2: Repeated Real Roots** For a root $p$ with multiplicity $m$: $$ \frac{C_1}{s-p} + \frac{C_2}{(s-p)^2} + \dots + \frac{C_m}{(s-p)^m} $$ $C_k = \frac{1}{(m-k)!} \lim_{s \to p} \frac{d^{m-k}}{ds^{m-k}} [(s-p)^m F(s)]$ For $m=2$: $C_2 = \lim_{s \to p} (s-p)^2 F(s)$, $C_1 = \lim_{s \to p} \frac{d}{ds} [(s-p)^2 F(s)]$ 4. **Case 3: Complex Conjugate Roots** For a pair of roots $s = \alpha \pm j\beta$: $$ \frac{A s + B}{(s-\alpha)^2 + \beta^2} $$ This form can often be matched with $e^{-at}\cos(\omega_0 t)$ and $e^{-at}\sin(\omega_0 t)$ forms after some algebraic manipulation. Alternatively, treat as distinct roots: $\frac{C}{s-(\alpha+j\beta)} + \frac{C^*}{s-(\alpha-j\beta)}$ where $C = \lim_{s \to \alpha+j\beta} (s-(\alpha+j\beta)) F(s)$. If $C = a+jb$, then $C^* = a-jb$. The inverse transform is $2|C|e^{\alpha t}\cos(\beta t + \angle C)u(t)$. 5. **Improper Fractions:** If $\text{deg}(N(s)) \ge \text{deg}(D(s))$, perform polynomial long division first to get a polynomial in $s$ plus a proper rational function. A polynomial term $s^k$ in $F(s)$ corresponds to $f^{(k)}(0^-)\delta(t)$ or similar, often indicating impulses. For most system analysis, $F(s)$ is proper. ### Applications - **Solving Linear Constant-Coefficient Differential Equations:** 1. Take the Laplace transform of both sides of the differential equation. 2. Use the differentiation property to convert derivatives into algebraic expressions involving $F(s)$ and initial conditions. 3. Solve the resulting algebraic equation for $F(s)$. 4. Find the inverse Laplace transform of $F(s)$ to get $f(t)$. - **Circuit Analysis:** Analyzing RLC circuits in the s-domain. - **Control Systems:** Analyzing system stability and response using transfer functions.