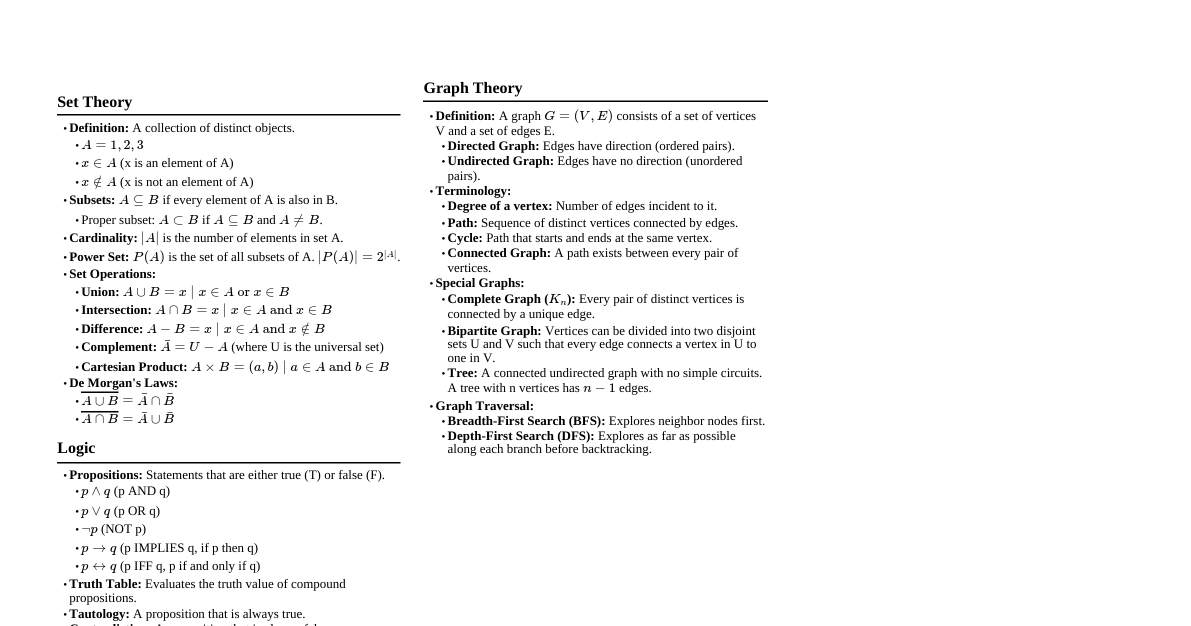

Mathematical Logic: Statements A statement is a sentence that is definitively true or definitively false. It cannot be both. Law of Excluded Middle: A statement is either true or false, but not both. It doesn't matter if we can't determine the truth value, only that one exists. Examples of Statements: "24 is divisible by 2." (True) "The square root of 2 is irrational." (True, requires proof) "If $x=3$, then $x^2=9$." (True) "If $x=3$, then $x^2=4$." (False) "The sum of two odd numbers is an even number." (True) Examples of Non-Statements: "Go home!" (Command) "What is your name?" (Question) "The only barber in a town shaves each and every man who does not shave himself." (Paradoxical, neither true nor false) "The positive integer $x$ is divisible by 2." (Truth depends on $x$, needs quantification) Truth Value: Whether a statement is true (T) or false (F). Logically Equivalent: Two statements are logically equivalent if they have the same truth values under the same circumstances. Types of Basic Statements: Obviously true or false. True or false, but requiring work to determine which. Combinations of quantified expressions that are true or false. Combining Statements: Negation (NOT) Definition: If $A$ is a statement, then not A (or $\neg A$) is its negation. Effect: Changes true statements to false, and false statements to true. Truth Table for NOT A: A not A T F F T Scope: 'not' applies only to what immediately follows it, unless brackets are used. E.g., not A or B means (not A) or B. Double Negation: not (not A) is logically equivalent to A. Venn Diagram: If circle A represents cases where A is true, then the area outside A represents cases where not A is true. Example: A: "29 is a prime number." not A: "29 is not a prime number." Combining Statements: AND Definition: The statement A and B (or $A \land B$) is true if and only if both A and B are true. Truth Table for A AND B: A B A and B T T T T F F F T F F F F Symmetry: A and B is logically equivalent to B and A. Associativity: (A and B) and C is logically equivalent to A and (B and C), and to A and B and C. Venn Diagram: Represented by the overlap (intersection) of circles A and B. Example: A: "21 is divisible by 3." (True) B: "All humans are mammals." (True) A and B: "21 is divisible by 3 and all humans are mammals." (True) Combining Statements: OR Definition (Inclusive OR): The statement A or B (or $A \lor B$) is true if A is true, or B is true, or both are true. Truth Table for A OR B: A B A or B T T T T F T F T T F F F Symmetry: A or B is logically equivalent to B or A. Associativity: (A or B) or C is logically equivalent to A or (B or C), and to A or B or C. Venn Diagram: Represented by the combined area (union) of circles A and B. Note: In mathematics, "or" always means inclusive or. If exclusive or is intended, it must be stated explicitly as "either A or B, but not both." Combining Statements: IF...THEN... ($\implies$) Definition: The statement if A then B (or $A \implies B$) means that if A is true, then B must also be true. Truth Table for IF A THEN B: A B if A then B T T T T F F F T T F F T Key Point: The only way for "if A then B" to be false is if A is true and B is false. If A is false, the statement is considered true regardless of B's truth value. Logically Equivalent Forms: if A then B is equivalent to B if A. if A then B is equivalent to not A or B . Venn Diagram: If A and B are circles, "if A then B" is true when A is entirely contained within B, or when A is false (outside A). The shaded area represents (not A) or B. Examples: "If $x=4$, then $x^2=8$." (False: A is true, B is false) "If $0=1$, then $2+2=5$." (True: A is false, B is false) "If $a$ and $b$ are odd integers, then $a+b$ is an even integer." (True) Combining Statements: ONLY IF Definition: A only if B is logically equivalent to if A then B . Truth Table for A ONLY IF B: (Same as "if A then B") A B A only if B T T T T F F F T T F F T Useful Tip: When you encounter "A only if B", you can replace it with "if A then B". Combining Statements: IF AND ONLY IF (IFF) ($\iff$) Definition: A if and only if B (or A iff B , or $A \iff B$) means that A and B always have the same truth value. It's true when A and B are both true, or A and B are both false. Logically Equivalent Forms: A iff B is equivalent to (A if B) and (A only if B). A iff B is equivalent to (if B then A) and (if A then B). Truth Table for A IFF B: A B A iff B T T T T F F F T F F F T Symmetry: A iff B is logically equivalent to B iff A. Venn Diagram: Represented by the complete overlap of circles A and B (they are the same circle). Example: "An integer is even if and only if it is not odd." Negating Compound Statements De Morgan's Laws: not (A and B) is logically equivalent to (not A) or (not B). not (A or B) is logically equivalent to (not A) and (not B). These equivalences are crucial for simplifying and understanding negated complex statements. Truth Table for not (A and B) vs (not A) or (not B): A B A and B not (A and B) not A not B (not A) or (not B) T T T F F F F T F F T F T T F T F T T F T F F F T T T T Converse and Contrapositive Statement: if A then B ($A \implies B$) Converse: if B then A ($B \implies A$) Not logically equivalent to the original statement. Example: "If $x$ is divisible by 3, then $x^2$ is divisible by 9." (True) Converse: "If $x^2$ is divisible by 9, then $x$ is divisible by 3." (False, e.g., $x=6$, $x^2=36$ (divisible by 9), but $x=6$ is divisible by 3. But consider $x=3$, $x^2=9$. The example in the document seems to imply this is true, but $x=3$ is divisible by 3, $x^2=9$ is divisible by 9. The original document provides an example where $x=6$ is divisible by $3$ and $x^2=36$ is divisible by $9$. This is true. The converse would be 'if $x^2$ is divisible by $9$, then $x$ is divisible by $3$.' If $x=4$, $x^2=16$ (not div by 9), $x$ (not div by 3). If $x=5$, $x^2=25$ (not div by 9), $x$ (not div by 3). If $x=6$, $x^2=36$ (div by 9), $x$ (div by 3). The converse is true. It is important to carefully check the specific examples provided in the source to ensure consistency. Let's stick with general mathematical understanding that a statement and its converse are not logically equivalent.) Contrapositive: if not B then not A ($\neg B \implies \neg A$) Logically equivalent to the original statement "if A then B". Example: "If $x$ is divisible by 3, then $x^2$ is divisible by 9." Contrapositive: "If $x^2$ is not divisible by 9, then $x$ is not divisible by 3." (Logically equivalent and true) Inverse: if not A then not B ($\neg A \implies \neg B$) Not logically equivalent to the original statement. It is logically equivalent to the converse. Summary of Equivalences: Statement ($A \implies B$) $\iff$ Contrapositive ($\neg B \implies \neg A$) Converse ($B \implies A$) $\iff$ Inverse ($\neg A \implies \neg B$) Truth Table for A $\implies$ B vs. $\neg$B $\implies$ $\neg$A: A B A $\implies$ B $\neg$B $\neg$A $\neg$B $\implies$ $\neg$A T T T F F T T F F T F F F T T F T T F F T T T T Necessary and Sufficient Conditions A is sufficient for B: Means "if A then B" ($A \implies B$). If A is true, B is guaranteed to be true. If A is false, B may or may not be true. Venn Diagram: Circle A is entirely contained within circle B. A is necessary for B: Means "if B then A" ($B \implies A$). If B is true, A is guaranteed to be true. If A is false, B must be false. Venn Diagram: Circle B is entirely contained within circle A. A is necessary and sufficient for B: Means "A if and only if B" ($A \iff B$). A and B always have the same truth value. Venn Diagram: Circles A and B are the same. Summary Table: Condition Logical Form Symbolic Form A is sufficient for B if A then B $A \implies B$ A is necessary for B if B then A $B \implies A$ A is necessary and sufficient for B A iff B $A \iff B$ Other Combinations: Necessary but not sufficient: $B \implies A$ but not $A \implies B$. Sufficient but not necessary: $A \implies B$ but not $B \implies A$. Neither necessary nor sufficient: Neither $A \implies B$ nor $B \implies A$. Quantifiers: FOR ALL ($\forall$) and THERE EXISTS ($\exists$) Quantifiers specify the scope of a variable in a statement. For All (Universal Quantifier): $\forall$ Means "for every", "for each", "for any". The statement holds true for every value of the variable in the specified domain. Example: "For all real $x$, $x^2 \ge 0$." (True) Example: "For all integers $x$, $x^2$ is an integer." (True) Example: "For all real $x$, $x^2$ is an integer." (False, e.g., $x=0.5$) There Exists (Existential Quantifier): $\exists$ Means "for some", "for at least one". Often followed by "such that". The statement holds true for at least one value of the variable in the specified domain. Example: "There exists a real $x$ such that $x^2 = 4$." (True, $x=2$ or $x=-2$) Example: "There exists a real $x$ such that $x^2$ is an integer." (True, e.g., $x=2$) Example: "There exists a real integer $x$ such that $x^2 = -4$." (False) Order of Quantifiers is Important: "For all positive real $x$, there exists a real $y$ such that $y^2 = x$." (True: for any $x$, we can find a $y$. If $x=4$, $y=2$. If $x=9$, $y=3$.) "There exists a real $y$ such that for all positive real $x$, $y^2 = x$." (False: there is no single $y$ that works for all $x$. If $y=2$, then $2^2=x$ means $x=4$. But this $y$ must work for all $x$, e.g., $x=9$, which means $2^2=9$, which is false). Negating Quantified Statements Negating "for all": not (for all $x$, $P(x)$) is equivalent to (there exists $x$ such that not $P(x)$). Symbolically: $\neg (\forall x, P(x)) \iff \exists x, \neg P(x)$. Example: Statement: "For all real $x$, $x^2 > 6$." (False) Negation: "There exists a real $x$ such that $x^2 \le 6$." (True, e.g., $x=1$) Negating "there exists": not (there exists $x$ such that $P(x)$) is equivalent to (for all $x$, not $P(x)$). Symbolically: $\neg (\exists x, P(x)) \iff \forall x, \neg P(x)$. Example: Statement: "There exists a real $x$ such that $x^2 Negation: "For all real $x$, $x^2 \ge 0$." (True) Mathematical Proof Definition: A rigorous and convincing explanation of why a mathematical statement is true. It must follow logical rules. Types of Proof: 1. Direct Deductive Proof Starts with a true statement (A) and proceeds through a series of logically valid steps ($A \implies P \implies Q \implies R \implies B$) to reach the desired conclusion (B). Each step must follow logically from the previous one, inheriting truth. Example: Prove "if $x$ is divisible by 3 then $x^2$ is exactly divisible by 9." Assume $x$ is divisible by 3. Then $x = 3n$ for some integer $n$. Squaring both sides: $x^2 = (3n)^2 = 9n^2$. Since $n$ is an integer, $n^2$ is an integer. Therefore, $x^2 = 9 \times (\text{integer})$, which means $x^2$ is divisible by 9. Conclusion: If $x$ is divisible by 3, then $x^2$ is divisible by 9. 2. Proof by Contradiction To prove a statement A: Assume that not A is true (the negation of A). Through a series of logical steps, show that this assumption leads to a contradiction (e.g., $B$ and not $B$). Since a contradiction cannot be true, the initial assumption (not A) must be false. Therefore, A must be true. Example: Prove "$\sqrt{2}$ is irrational." Assume $\sqrt{2}$ is rational. If $\sqrt{2}$ is rational, it can be written as a fraction $\frac{a}{b}$ in its lowest terms, where $a, b$ are integers and $b \ne 0$, and $a, b$ have no common factors. $\sqrt{2} = \frac{a}{b} \implies 2 = \frac{a^2}{b^2} \implies 2b^2 = a^2$. This means $a^2$ is even. If $a^2$ is even, then $a$ must be even (since an odd number squared is odd). If $a$ is even, then $a = 2k$ for some integer $k$. Substitute $a=2k$ into $2b^2 = a^2$: $2b^2 = (2k)^2 = 4k^2$. Divide by 2: $b^2 = 2k^2$. This means $b^2$ is even. If $b^2$ is even, then $b$ must be even. So, both $a$ and $b$ are even. This contradicts our initial assumption that $a$ and $b$ have no common factors (as they both have a common factor of 2). Therefore, the assumption that $\sqrt{2}$ is rational must be false. Conclusion: $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational. 3. Proof by Contrapositive To prove "if A then B", prove its contrapositive "if not B then not A". Since the contrapositive is logically equivalent to the original statement, proving one proves the other. Often easier when dealing with negative conditions. Example: Prove "for any non-zero integer $x$: if $x^3$ is odd then $x$ is odd." The contrapositive is: "for any non-zero integer $x$: if $x$ is not odd then $x^3$ is not odd." This can be rephrased as: "for any non-zero integer $x$: if $x$ is even then $x^3$ is even." Assume $x$ is even. Then $x = 2p$ for some integer $p$. $x^3 = (2p)^3 = 8p^3$. Since $8p^3 = 2(4p^3)$ and $4p^3$ is an integer, $x^3$ is even. Conclusion: The contrapositive is true, therefore the original statement is true. 4. Disproof by Counterexample To show a universal statement ("for all X, P(X) is true") is false, you only need to find one specific example (a counterexample) for which P(X) is false. Example: Disprove "all prime numbers are odd." Counterexample: 2 is a prime number, but 2 is even. Conclusion: The statement is false. For "if A then B": A counterexample is a case where A is true, but B is false. Example: Disprove "if $x Counterexample: Let $x = -2$ and $y = 1$. Here, $x But $x^2 = (-2)^2 = 4$ and $y^2 = 1^2 = 1$. So $x^2 Conclusion: The statement is false. Identifying Errors in Proofs Common Errors: Assuming the Converse: Just because "if A then B" is true, it doesn't mean "if B then A" is true. Dividing by Zero: Never divide by an expression that could be zero. This often creates false equivalences. Example: $x=y \Rightarrow x^2=xy \Rightarrow x^2-y^2=xy-y^2 \Rightarrow (x-y)(x+y)=y(x-y)$. If $x=y$, then $(x-y)=0$, so dividing by $(x-y)$ is invalid. If one proceeds, $x+y=y \Rightarrow y+y=y \Rightarrow 2y=y \Rightarrow 2=1$ (false). Incorrectly Squaring Equations/Inequalities: Squaring can introduce extraneous solutions or change the direction of inequalities. Example (Equations): $x = \sqrt{25}$ implies $x=5$. Squaring gives $x^2=25$, which has solutions $x=5$ and $x=-5$. The extra solution $x=-5$ is extraneous to the original equation. Example (Inequalities): $-5 Multiplying/Dividing Inequalities by Negative Numbers: Must reverse the inequality sign. Example: $1 -2$. Applying Functions to Inequalities: Not all functions preserve inequalities. For example, $\cos(\frac{\pi}{3}) Careless Negation: Especially with compound statements and quantifiers. Use De Morgan's laws and quantifier negation rules correctly. Circular Reasoning: Assuming what you are trying to prove. TMUA Tips, Strategies, and Tricks General Approach to Logic and Proof Questions: Read Carefully: Pay close attention to keywords like "if," "only if," "and," "or," "not," "for all," "there exists." Their precise meaning is critical. Translate: If a statement is complex, try to break it down into simpler components (A, B, C) and express it symbolically if comfortable ($\land, \lor, \neg, \implies, \iff, \forall, \exists$). Truth Tables: For compound statements, mentally (or actually) construct truth tables to understand the conditions under which the statement is true or false. This is especially useful for checking logical equivalence. Venn Diagrams: Use Venn diagrams for visualizing relationships between statements (especially for AND, OR, IF...THEN...). They can provide an intuitive understanding. Test Cases: For "for all" statements, try to find a counterexample. For "there exists" statements, try to find an example. This helps determine truth value. Specifically for Proofs: Understand the Goal: Clearly identify what you need to prove. Choose the Right Method: Direct Proof: If the connection between premise and conclusion seems straightforward. Proof by Contradiction: Often useful for proving existence, non-existence, or irrationality ($\sqrt{2}$ is irrational, there are infinitely many primes). Assume the opposite and look for a logical inconsistency. Proof by Contrapositive: Excellent when negating the conclusion simplifies the problem or makes an implication easier to see. E.g., proving "if it's raining, the ground is wet" by proving "if the ground is not wet, it's not raining". Disproof by Counterexample: The quickest way to show a universal statement is false. Don't try to prove it's false generally; just find one case. Be Rigorous: Every step must be logically sound. Don't jump to conclusions. Check for Common Errors: Actively look for the pitfalls mentioned above (division by zero, incorrect squaring, negation mistakes, assuming the converse). For Necessary and Sufficient Conditions: "A is sufficient for B" $\iff$ "if A then B". Think: A is enough to guarantee B. "A is necessary for B" $\iff$ "if B then A". Think: B cannot happen without A. "A is necessary and sufficient for B" $\iff$ "A iff B". Think: A and B are equivalent. Practice translating between these phrases and their "if...then..." forms. For Quantifiers: "For all" ($\forall$): Requires the statement to be true for every single instance . One counterexample makes it false. "There exists" ($\exists$): Requires the statement to be true for at least one instance . One example makes it true. Order Matters: Be extremely careful with mixed quantifiers ($\forall x \exists y$ vs. $\exists y \forall x$). They mean very different things. Visualize: $\forall x \exists y$: For each specific $x$, you can find a *possibly different* $y$. $\exists y \forall x$: There is *one specific* $y$ that works for *all* $x$. Negation: Remember $\neg \forall \iff \exists \neg$ and $\neg \exists \iff \forall \neg$. This is a common test point. General Study Tips: Active Learning: Don't just read; actively work through examples, try to construct your own, and explain concepts to someone else (or yourself). Practice Past Papers: Identify questions related to logic and proof. Analyze the model answers to understand the expected level of detail and rigor. Footnotes: While the document says to ignore TMUA footnotes, understanding the philosophical underpinnings can deepen your understanding of why certain rules exist.