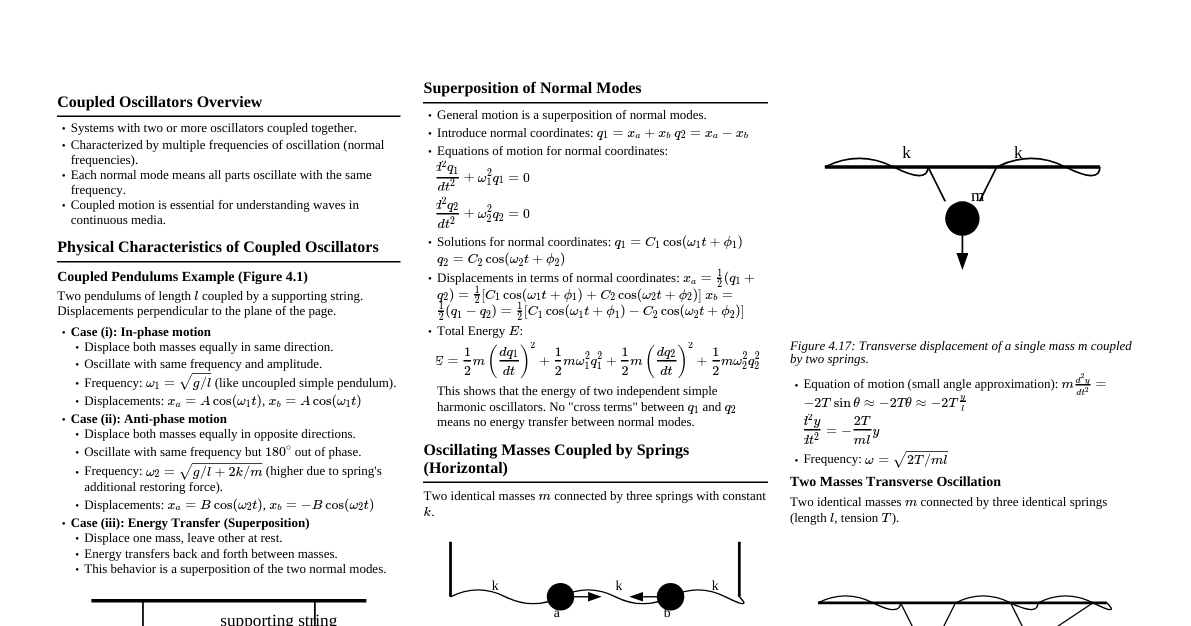

Coupled Oscillators: Introduction Systems with two or more coupled oscillators have multiple frequencies of oscillation, unlike simple harmonic oscillators (SHOs) with a single natural frequency. Normal Modes: Distinct ways a system can oscillate, where all parts oscillate with the same frequency. Normal Frequencies: The frequencies associated with normal modes. Coupled motion is prevalent in real physical systems (e.g., vibrating atoms in a crystal, wave motion in taut strings). Physical Characteristics of Coupled Oscillators Two Coupled Pendulums (String Coupling) Setup: Two simple pendulums of equal length $l$ coupled by a supporting string. Observation (i) - In-phase motion: Displace both pendulums by the same amount in the same direction. Release: Oscillate back and forth in the same direction, with the same frequency and amplitude. This is the first normal mode . Observation (ii) - Anti-phase motion: Displace both pendulums by the same amount in opposite directions. Release: Oscillate back and forth in opposite directions, with the same frequency (slightly different from in-phase motion). This is the second normal mode . Observation (iii) - Energy Transfer: Displace one mass, leave the other at rest. Release: Displaced mass oscillates with decreasing amplitude, while the initially resting mass starts oscillating with increasing amplitude. Energy is repeatedly transferred between the two masses. This behavior is a superposition of the two normal modes. Normal Modes of Oscillation Two Coupled Pendulums (Spring Coupling) Setup: Two pendulums (mass $m$, length $l$) connected by a light horizontal spring (spring constant $k$). Displacements $x_a, x_b$. Case (i) - First Normal Mode (In-phase): Displace $x_a = x_b = A$. Spring remains at unstretched length. Oscillation frequency: $\omega_1 = \sqrt{g/l}$. Displacements: $x_a = A \cos \omega_1 t$, $x_b = A \cos \omega_1 t$. Masses oscillate in phase with the same frequency and amplitude. Case (ii) - Second Normal Mode (Anti-phase): Displace $x_a = A$, $x_b = -A$. Spring alternately stretched and compressed, providing additional restoring force. Equation of motion for mass $a$: $m \frac{d^2 x_a}{dt^2} = -\frac{mgx_a}{l} - 2kx_a$. This simplifies to $\frac{d^2 x_a}{dt^2} + \omega_2^2 x_a = 0$, where $\omega_2^2 = \frac{g}{l} + \frac{2k}{m}$. Oscillation frequency: $\omega_2 = \sqrt{g/l + 2k/m}$. Note $\omega_2 > \omega_1$. Displacements: $x_a = B \cos \omega_2 t$, $x_b = -B \cos \omega_2 t$. Masses oscillate $180^\circ$ out of phase with the same frequency and amplitude. Characteristics of Normal Modes: Both masses oscillate at the same frequency . Each mass performs SHM with constant amplitude. A well-defined phase difference between the two masses (either $0$ or $\pi$). Once started in a normal mode, the system stays in that mode. Superposition of Normal Modes General motion of a coupled oscillator is a superposition of its normal modes. Equations of Motion: For mass $a$: $m \frac{d^2 x_a}{dt^2} = -\frac{mgx_a}{l} - k(x_a - x_b)$ For mass $b$: $m \frac{d^2 x_b}{dt^2} = -\frac{mgx_b}{l} + k(x_a - x_b)$ These coupled equations must be solved simultaneously. Normal Coordinates: Introduce $q_1 = x_a + x_b$ and $q_2 = x_a - x_b$. Adding equations: $\frac{d^2(x_a+x_b)}{dt^2} + \frac{g}{l}(x_a+x_b) = 0 \implies \frac{d^2q_1}{dt^2} + \omega_1^2 q_1 = 0$. Subtracting equations: $\frac{d^2(x_a-x_b)}{dt^2} + (\frac{g}{l} + \frac{2k}{m})(x_a-x_b) = 0 \implies \frac{d^2q_2}{dt^2} + \omega_2^2 q_2 = 0$. These are independent SHM equations for $q_1$ and $q_2$. General Solutions for Normal Coordinates: $q_1 = C_1 \cos(\omega_1 t + \phi_1)$ $q_2 = C_2 \cos(\omega_2 t + \phi_2)$ Displacements in terms of Normal Coordinates: $x_a = \frac{1}{2}(q_1 + q_2) = \frac{1}{2}[C_1 \cos(\omega_1 t + \phi_1) + C_2 \cos(\omega_2 t + \phi_2)]$ $x_b = \frac{1}{2}(q_1 - q_2) = \frac{1}{2}[C_1 \cos(\omega_1 t + \phi_1) - C_2 \cos(\omega_2 t + \phi_2)]$ Energy of the System: Can be expressed as the sum of energies of two independent SHOs in terms of $q_1$ and $q_2$, with no cross-terms. Beating Phenomenon (Energy Transfer): If one pendulum is initially displaced ($x_a=A, x_b=0$), the motion is a superposition of both modes. The amplitude of each mass varies, leading to energy exchange. Oscillating Masses Coupled by Springs Setup: Two identical masses $m$ connected by three springs, each with spring constant $k$. Outer springs connected to rigid walls. Equations of Motion: $m \frac{d^2 x_a}{dt^2} = -k x_a + k(x_b - x_a) = k x_b - 2k x_a$ $m \frac{d^2 x_b}{dt^2} = -k(x_b - x_a) - k x_b = k x_a - 2k x_b$ Normal Mode Solutions: Assume $x_a = A \cos \omega t$ and $x_b = B \cos \omega t$. Substituting and solving yields a quadratic equation for $\omega^2$: $(2k - m\omega^2)^2 = k^2$. Normal Frequencies: $\omega_1^2 = k/m$ (First normal mode: $A=B$, masses move in the same direction). $\omega_2^2 = 3k/m$ (Second normal mode: $A=-B$, masses move in opposite directions). Matrix Approach: Equations can be written as an eigenvalue problem: $$ \begin{pmatrix} 2k/m & -k/m \\ -k/m & 2k/m \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} A \\ B \end{pmatrix} = \omega^2 \begin{pmatrix} A \\ B \end{pmatrix} $$ The solutions for $\omega^2$ are eigenvalues, and $(A, B)$ are eigenvectors. Forced Oscillations of Coupled Oscillators When a coupled oscillator is driven by an external force, large amplitude oscillations (resonance) occur when the driving frequency $\omega$ approaches a normal frequency ($\omega_1$ or $\omega_2$). Example: Two masses coupled by springs, with one end driven harmonically: $\xi = a \cos \omega t$. Resulting equations for normal coordinates $q_1 = x_a + x_b$ and $q_2 = x_a - x_b$ become: $$ \frac{d^2q_1}{dt^2} + \frac{k}{m}q_1 = \frac{F_0}{m} \cos \omega t $$ $$ \frac{d^2q_2}{dt^2} + \frac{3k}{m}q_2 = \frac{F_0}{m} \cos \omega t $$ where $F_0 = ka$. These are equations for forced SHOs. Amplitudes $C_1 = \frac{F_0/m}{(\omega_1^2 - \omega^2)}$ and $C_2 = \frac{F_0/m}{(\omega_2^2 - \omega^2)}$. If $\omega \approx \omega_1$, then $|C_1| \gg |C_2|$, so $x_a \approx x_b$ (in-phase oscillation). If $\omega \approx \omega_2$, then $|C_2| \gg |C_1|$, so $x_a \approx -x_b$ (anti-phase oscillation). This principle is used in absorption spectroscopy to determine normal mode frequencies of molecules (e.g., CO$_2$ vibrations). Transverse Oscillations Single Mass with Two Springs Setup: Mass $m$ connected by two springs (constant $k$, length $l$, tension $T$) undergoing transverse displacement $y$. For small displacements, tension $T$ is approximately constant. Equation of motion: $m \frac{d^2 y}{dt^2} = -2T \sin \theta \approx -2T \frac{y}{l}$. Frequency of SHM: $\omega = \sqrt{2T/ml}$. Two Coupled Masses with Springs Setup: Two equal masses connected by three identical springs, under tension $T$, undergoing transverse displacements $y_a, y_b$. Equations of Motion: $m \frac{d^2 y_a}{dt^2} = \frac{T}{l}(y_b - 2y_a)$ $m \frac{d^2 y_b}{dt^2} = \frac{T}{l}(y_a - 2y_b)$ Solving for normal modes (similar to longitudinal case): $\omega_1^2 = T/ml$ (First normal mode: $A=B$, masses move in same direction). $\omega_2^2 = 3T/ml$ (Second normal mode: $A=-B$, masses move in opposite directions). These normal modes resemble standing waves on a taut string, bridging the concept of coupled oscillators to wave phenomena.