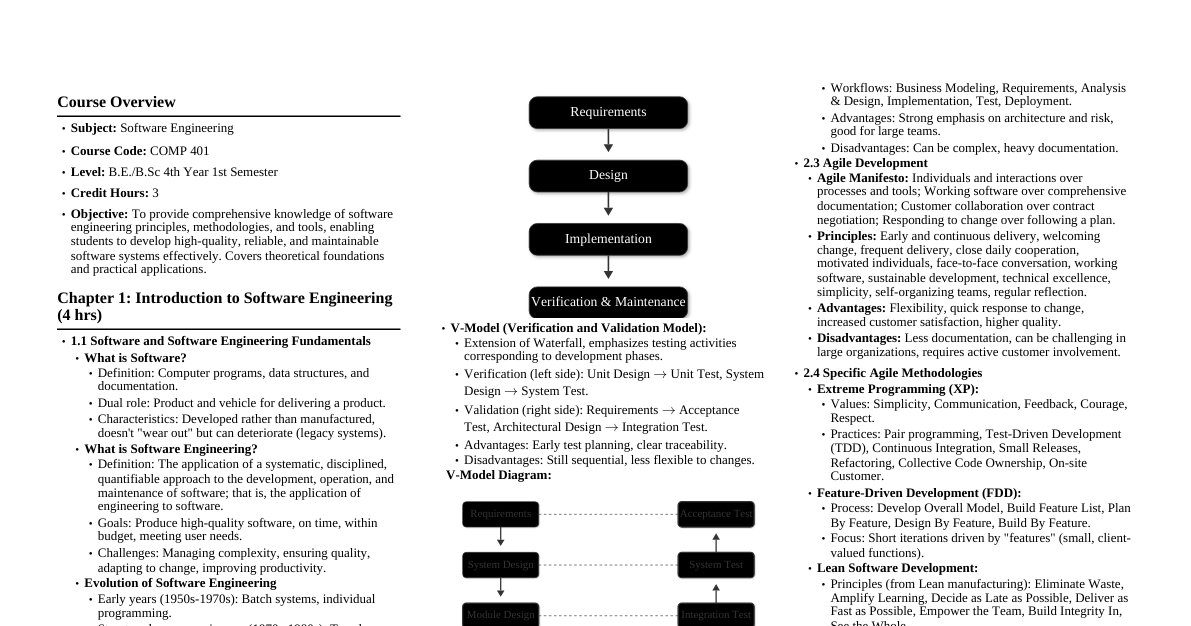

I. Introduction to Software Engineering 1.1 The Nature of Software Software is both a product and a vehicle for delivering a product. Software is developed or engineered , not manufactured. Software doesn't "wear out," but it deteriorates due to change. Most software is custom built , moving toward component-based construction. 1.2 Software Application Domains System software: Services other programs (e.g., OS, compilers). Application software: Solves specific business needs (e.g., ERP). Engineering/Scientific software: "Number crunching" algorithms (e.g., CAD, simulations). Embedded software: Resides within a product/system (e.g., car controls, microwave keypad). Product-line software: Specific capability for many customers (e.g., word processors). Web applications (WebApps): Network-centric software (e.g., e-commerce, social media). Artificial intelligence software: Non-numerical algorithms (e.g., robotics, expert systems). 1.3 The Unique Nature of WebApps Network intensiveness: Resides on a network, serves diverse clients. Concurrency: Many users access simultaneously. Unpredictable load: User numbers vary greatly. Performance: Must be responsive; users go elsewhere if slow. Availability: Often demanded 24/7/365. Data driven: Uses hypermedia to present content, accesses databases. Content sensitive: Quality and aesthetics of content are crucial. Continuous evolution: Updates minute-by-minute or for each request. Immediacy: Fast time-to-market (days or weeks). Security: Strong measures needed due to network access. Aesthetics: Look and feel are important for success. 1.4 Software Engineering Defined Fritz Bauer (1969): "The establishment and use of sound engineering principles in order to obtain economically software that is reliable and works efficiently on real machines." IEEE: "The application of a systematic, disciplined, quantifiable approach to the development, operation, and maintenance of software." Software engineering is a layered technology : Quality Focus: Bedrock. Process: Foundation, glue. Methods: Technical "how-to's." Tools: Automated support. 1.5 Software Myths Management Myths: "We have standards, so quality is assured." (Reality: Standards often unused/outdated). "Adding more programmers to a late project will catch it up." (Reality: Makes it later, Brooks' Law). "If I outsource, I can relax." (Reality: Requires internal management expertise). Customer Myths: "General objectives are enough; details later." (Reality: Ambiguity leads to disaster). "Requirements change, but software is flexible." (Reality: Cost of change increases non-linearly with time). Practitioner Myths: "Once it runs, my job is done." (Reality: 60-80% effort is post-delivery maintenance). "Cannot assess quality until it runs." (Reality: Technical reviews find errors earlier). "Only deliverable is the program." (Reality: Work products like models, docs are crucial). "SE means voluminous docs and slows us down." (Reality: Focus on quality reduces rework, speeds delivery). II. The Software Process 2.1 Generic Process Model Process: Collection of activities, actions, and tasks to create a work product. Framework Activities: Applicable to all software projects. Communication: Understand objectives, gather requirements. Planning: Create a "map" (project plan), define tasks, risks, resources, schedule. Modeling: Create "sketches" (models) for requirements and design. Construction: Code generation and testing. Deployment: Deliver software increment, get feedback. Umbrella Activities: Applied throughout the process. Software project tracking and control Risk management Software quality assurance (SQA) Technical reviews Measurement Software configuration management (SCM) Reusability management Work product preparation and production Process Flow: Describes how activities are organized. Linear: Sequential execution ($A \rightarrow B \rightarrow C$). Iterative: Repeats activities ($A \rightarrow B \rightarrow A \rightarrow C$). Evolutionary: Circular, leads to more complete versions. Parallel: Concurrent execution ($A$ and $B$ simultaneously). 2.2 Prescriptive Process Models Waterfall Model (Classic Life Cycle): Systematic, sequential approach. Communication $\rightarrow$ Planning $\rightarrow$ Modeling $\rightarrow$ Construction $\rightarrow$ Deployment. V-Model: Illustrates verification and validation (V&V) actions against earlier engineering work. When to use: Requirements are well-understood and stable. Weaknesses: Linear flow rarely followed, difficulty accommodating change, late delivery of working software. Incremental Process Models: Combines linear and parallel flows in staggered fashion. Delivers a series of "increments" (stripped-down versions) of the software. Customer uses/evaluates, plan for next increment developed. Useful when requirements are defined but overall scope is large, or early functionality is needed. Evolutionary Process Models: Explicitly designed to accommodate evolving products. Prototyping: For fuzzy requirements. Build a quick prototype, get feedback, refine requirements. Can be "throwaway" or evolve into actual system. Risks: Stakeholders may treat prototype as final, implementation compromises become permanent. Spiral Model (Boehm): Couples iterative prototyping with controlled sequential aspects. Risk-driven; each loop around spiral leads to more complete version. Adaptable throughout life cycle (concept, new product, enhancement). Weaknesses: Difficult to convince customers, demands risk assessment expertise. Concurrent Models (Concurrent Engineering): Activities exist concurrently in different states. Event-driven transitions between states for activities (e.g., "under development," "awaiting changes"). Applicable to all types of development, provides accurate project state. 2.3 Specialized Process Models Component-Based Development (CBD): Constructs applications from prepackaged software components (COTS). Steps: Research components, consider integration, design architecture, integrate, test. Promotes reuse, reduces cycle time and cost. Formal Methods Model: Mathematically based techniques for specification, development, and verification. Aims for defect-free software, eliminates ambiguity/inconsistency early. Weaknesses: Time-consuming/expensive, requires specialized skills, difficult communication with non-technical stakeholders. Used for safety-critical software. Aspect-Oriented Software Development (AOSD): Addresses "crosscutting concerns" (properties spanning multiple functions/features). Aims to localize crosscutting concerns into "aspects" for better modularity. Process likely combines evolutionary and concurrent models. III. Agile Development 3.1 What is Agility? Ability to respond appropriately to change. Emphasizes rapid delivery of operational software, customer collaboration, team autonomy. Adapts incrementally to project and technical conditions. 3.2 Agile Principles (Manifesto for Agile Software Development) Satisfy customer through early and continuous delivery. Welcome changing requirements. Deliver working software frequently (weeks to months). Business people and developers work together daily. Build projects around motivated individuals. Face-to-face conversation is most efficient. Working software is primary measure of progress. Agile processes promote sustainable development. Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design. Simplicity (maximizing work not done) is essential. Best architectures, requirements, designs emerge from self-organizing teams. Regularly reflect on effectiveness and adjust behavior. 3.3 Extreme Programming (XP) Most widely used agile approach. Values: Communication, simplicity, feedback, courage, respect. Process: Planning: User stories (customer-written, prioritized), project velocity (stories/release). Design: KIS (keep it simple), CRC cards, spike solutions (prototypes), refactoring (improves internal structure without altering external behavior). Coding: Unit tests before coding, pair programming (real-time problem solving & QA), continuous integration. Testing: Automated unit tests, acceptance tests (customer-specified, based on user stories). Industrial XP (IXP): Refines XP for large organizations. Adds: Readiness assessment, project community, project chartering, test-driven management, retrospectives, continuous learning. 3.4 Other Agile Process Models Adaptive Software Development (ASD): Focuses on human collaboration, self-organization. Phases: Speculation (planning), collaboration (teamwork), learning (feedback, reviews). Scrum: Agile method for projects with tight timelines, changing requirements. Backlog: Prioritized requirements list. Sprints: Fixed-length work units (e.g., 30 days). Scrum meetings: Daily 15-min meetings to track progress, obstacles. Demos: Deliver increment to customer for evaluation. Dynamic Systems Development Method (DSDM): Iterative, incremental prototyping. 80% of application in 20% of time. Life cycle: Feasibility, Business study, Functional model iteration, Design and build iteration, Implementation. Crystal: Family of agile methods for different project types, emphasizing "maneuverability." Feature Driven Development (FDD): Object-oriented, focuses on "features" (client-valued function, implemented in $\le 2$ weeks). Processes: Develop overall model, build feature list, plan by feature, design by feature, build by feature. Lean Software Development (LSD): Adapts lean manufacturing principles. Principles: Eliminate waste, build quality in, create knowledge, defer commitment, deliver fast, respect people, optimize the whole. Agile Modeling (AM): Practice-based methodology for effective, lightweight modeling and documentation. Principles: Model with purpose, use multiple models, travel light, amenable to change, useful over perfect, adapt locally, content $>$ representation, trust instincts, get feedback. Agile Unified Process (AUP): "Serial in the large, iterative in the small." Phases: Inception, elaboration, construction, transition. Activities in iterations: Modeling, implementation, testing, deployment, configuration & project management, environment management. IV. Requirements Engineering 4.1 Requirements Engineering Tasks Inception: Establish basic understanding of problem, people, solution, and communication. Elicitation: Gather requirements from stakeholders; addresses scope, understanding, and volatility problems. Methods include collaborative gathering, QFD, usage scenarios. Elaboration: Expand and refine initial requirements into a detailed requirements model (function, behavior, information). Driven by user scenarios. Negotiation: Reconcile conflicting requirements from different stakeholders, prioritize, assess cost/risk. Aims for "win-win." Specification: Document requirements (written document, models, math, prototypes, etc.). Validation: Assess work products for quality (unambiguous, consistent, complete, correct, testable). Primary mechanism: technical review. Management: Identify, control, track requirements and changes. 4.2 Collaborative Requirements Gathering Meetings with software engineers and stakeholders. Rules for participation, agenda, facilitator, definition mechanism (whiteboards, etc.). Goal: Identify problem, propose solutions, negotiate approaches, specify requirements. Categorize stakeholder input: commonality, conflict, inconsistency. 4.3 Quality Function Deployment (QFD) Translates customer needs into technical requirements. Normal requirements: Stated objectives/goals. Expected requirements: Implicit, fundamental needs (e.g., ease of use). Exciting requirements: Go beyond expectations, delight users. 4.4 Usage Scenarios (Use Cases) Describe how an end user (actor) interacts with the system. Can be narrative text, ordered tasks, template-based, or diagrammatic. Actors: People or devices using the system (roles). Key questions: Primary/secondary actors, goals, preconditions, tasks, exceptions, variations, system info. Refining: Identify alternative interactions, error conditions, other behaviors (exceptions). Formal Use Case: Template-based, includes goal, preconditions, trigger, scenario, exceptions, priority, frequency, channels. UML Use Case Diagram: Overview of all use cases and their relationships. 4.5 Requirements Modeling Elements Scenario-based elements: Use cases, activity diagrams, swimlane diagrams. Class-based elements: Classes, attributes, operations, relationships, collaborations (e.g., CRC models, class diagrams). Behavioral elements: How software reacts to events (e.g., state diagrams, sequence diagrams). Flow-oriented elements: How information transforms through the system (e.g., data flow diagrams). 4.6 Analysis Patterns Reusable solutions (class, function, behavior) for recurring problems in an application domain. Document problem, context, solution, forces, consequences, known uses. Example: Actuator-Sensor pattern for embedded systems. V. Design Concepts 5.1 Design within the Context of SE Translates requirements into a "blueprint" for construction. Iterative process, from high-level abstraction to detailed implementation. Design model elements: Data/class design, architectural design, interface design, component-level design, deployment-level design. Importance: Fosters quality, foundation for all subsequent activities. 5.2 Software Quality Guidelines and Attributes Good design characteristics: Implements requirements (explicit/implicit), readable, complete (data, functional, behavioral). Quality guidelines: Recognizable architecture, modular, distinct representations (data, architecture, interfaces, components), appropriate data structures, independent functional components, simple interfaces, repeatable method, effective notation. Quality attributes (FURPS): Functionality: Feature set, capabilities, security. Usability: Human factors, aesthetics, consistency, documentation. Reliability: Failure frequency/severity, accuracy, MTTF, recovery. Performance: Speed, response time, resource consumption. Supportability: Extensibility, adaptability, serviceability (maintainability), testability, compatibility. 5.3 Design Concepts Abstraction: Procedural (sequence of instructions for limited function) and data (named collection of data describing object). Architecture: Overall structure of software, components, interactions, data. Patterns: Proven solution to a recurring problem in a context (creational, structural, behavioral). Separation of Concerns: Subdivide complex problems into independent pieces. Modularity: Software divided into separately named and addressable components. Information Hiding: Modules specified so internal algorithms/data are inaccessible to others without need. Functional Independence: Modules with "single-minded" function and minimal interaction (high cohesion, low coupling). Refinement (Stepwise): Top-down strategy, successively refining levels of procedural detail. Aspects: Representation of a crosscutting concern (characteristic spanning entire system). Refactoring: Reorganization technique to simplify design/code without changing function/behavior. Object-Oriented Design Concepts: Classes, objects, inheritance, messages, polymorphism. Design Classes: Refine analysis classes, add implementation detail. Types: User interface, business domain, process, persistent, system. Well-formed: Complete & sufficient, primitiveness, high cohesion, low coupling. VI. Architectural Design 6.1 Architectural Styles Template for construction, structure for system components. Data-centered architectures: Central data store accessed by independent clients. Data-flow architectures: Input data transformed through series of computational components (pipe-and-filter). Call and return architectures: Hierarchical program structure (main program/subprogram, remote procedure call). Object-oriented architectures: Components encapsulate data and operations, communicate via message passing. Layered architectures: Defined layers, each accomplishing operations progressively closer to machine. 6.2 Architectural Patterns Address application-specific problems within a context. Example domains: Access control, concurrency, distribution, persistence. 6.3 Architectural Design Steps Representing System in Context: Architectural Context Diagram (ACD) shows interaction with external entities (superordinate, subordinate, peer, actors). Defining Archetypes: Core abstractions critical to system design. Refining Architecture into Components: Identify components from analysis classes and infrastructure. Describing Instantiations: Apply architecture to specific problem to demonstrate appropriateness. 6.4 Assessing Alternative Architectural Designs Architecture Trade-Off Analysis Method (ATAM): Iterative evaluation process. Collect scenarios, elicit requirements, describe styles, evaluate quality attributes, identify sensitivity points, critique architectures. Architectural Complexity: Consider dependencies (sharing, flow, constrained) between components. Architectural Description Languages (ADLs): Formal semantics and syntax for architecture description. 6.5 Architectural Mapping using Data Flow Structured design maps Data Flow Diagrams (DFDs) to software architecture. Transform flow: Linear quality, data flows in, processed at transform center, flows out. Steps: Review system model, refine DFDs, determine flow type, isolate transform center, first-level factoring, second-level factoring, refine using heuristics. VII. Component-Level Design 7.1 What is a Component? Modular, deployable, replaceable part of a system that encapsulates implementation and exposes interfaces. Object-Oriented View: Component contains set of collaborating classes, fully elaborated. Traditional View: Functional element with processing logic, internal data structures, and interface. Roles: control, problem domain, infrastructure. Process-Related View: Reusable components selected from catalog. 7.2 Designing Class-Based Components Basic Design Principles: Open-Closed Principle (OCP): Open for extension, closed for modification. Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP): Subclasses substitutable for base classes. Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP): Depend on abstractions, not concretions. Interface Segregation Principle (ISP): Many client-specific interfaces $>$ one general-purpose interface. Packaging Principles: Release Reuse Equivalency Principle (REP): Granule of reuse is granule of release. Common Closure Principle (CCP): Classes that change together belong together. Common Reuse Principle (CRP): Classes not reused together should not be grouped together. Component-Level Design Guidelines: Naming conventions, interface representation, dependencies and inheritance modeling. Cohesion: "Single-mindedness" of a component. Types: functional, layer, communicational. Coupling: Interdependence among modules. Types: content, common, control, stamp, data, routine call, type use, inclusion, external. 7.3 Conducting Component-Level Design Identify problem domain design classes. Identify infrastructure domain design classes. Elaborate design classes (interfaces, attributes, operations). Specify message details for collaborations. Identify appropriate interfaces for each component. Elaborate attributes, define data types and structures. Describe processing flow within each operation (pseudocode or activity diagram). Describe persistent data sources and managing classes. Elaborate behavioral representations for class/component (state diagrams). Elaborate deployment diagrams (instance form). Refactor and consider alternatives. VIII. WebApp Design 8.1 WebApp Design Quality Core attributes: Usability, functionality, reliability, efficiency, maintainability. Additional attributes: Security, availability, scalability, time-to-market. Design Goals: Simplicity, consistency, identity, robustness, navigability, visual appeal, compatibility. 8.2 WebApp Design Pyramid Levels: Interface design, aesthetic design, content design, navigation design, architecture design, component design. 8.3 WebApp Interface Design Establishes consistent window, guides user, organizes navigation. Interaction mechanisms: navigation menus, graphic icons, graphic images. 8.4 Aesthetic Design (Graphic Design) Artistic endeavor, complements technical aspects. Layout Issues: Use of white space, content emphasis, top-left to bottom-right flow, grouping elements, minimize scrolling, consider resolution. Graphic Design Issues: Color schemes, text types, supplementary media. 8.5 Content Design Design representation for content objects and their relationships. Content objects: text, graphics, video, audio. "Chunking" content for WebApp pages. 8.6 Architecture Design (WebApp) Infrastructure for WebApp business objectives. Content Architecture: Hypermedia structure (linear, grid, hierarchical, networked). WebApp Architecture: Manages user interaction, processing, navigation, content presentation. Example: Model-View-Controller (MVC). 8.7 Navigation Design Defines pathways for user access to content/functions. Navigation Semantics: Identify Navigation Semantic Units (NSUs) and Ways of Navigating (WoNs) based on user roles/use cases. Navigation Syntax: Mechanics of navigation (links, bars, tabs, site maps, search engines). 8.8 Component-Level Design (WebApp) Sophisticated processing functions (dynamic content, computation, database access, external interfaces). Similar to traditional software components design. 8.9 Object-Oriented Hypermedia Design Method (OOHDM) Four design activities: Conceptual Design: Subsystems, classes, relationships for application domain. Navigational Design: Navigational classes (nodes, links, anchors, access structures), grouping into contexts. Abstract Interface Design: Specifies interface objects (layout, behavior). Implementation: Characterizes classes, navigation, interface for target environment. IX. Quality Management 9.1 What is Quality? Garvin's Quality Dimensions: Performance, feature, reliability, conformance, durability, serviceability, aesthetics, perception. McCall's Quality Factors: Correctness, reliability, efficiency, integrity, usability, maintainability, flexibility, testability, portability, reusability, interoperability. ISO 9126 Quality Factors: Functionality, reliability, usability, efficiency, maintainability, portability (with sub-attributes). Targeted Quality Factors: Intuitiveness, efficiency, robustness, richness. Software Quality: Effective process $\rightarrow$ useful product $\rightarrow$ measurable value. 9.2 The Software Quality Dilemma Balance between producing high-quality software and meeting market demands (time/cost). "Good Enough" Software: Delivers high-quality core functions, but may have known bugs in obscure features. Risky for small companies or critical domains. Cost of Quality: Prevention costs: Planning, requirements, design, training. Appraisal costs: Reviews, metrics, testing. Failure costs: Internal (rework) and external (customer support, reputation). Cost to fix an error increases significantly later in the process. Risks: Low quality increases project and business risks. Negligence and Liability: Poor quality can lead to legal issues. Quality and Security: Low-quality software is easier to hack. Focus on quality, especially architectural design ("flaws"), improves security. Impact of Management Actions: Unrealistic estimates, poor scheduling, ignored risks can compromise quality. 9.3 Achieving Software Quality Software engineering methods (analysis, design). Project management techniques (estimation, scheduling, risk management). Quality control (reviews, testing, measurement). Software quality assurance (SQA) infrastructure. X. Review Techniques 10.1 Cost Impact of Software Defects Errors (found before release) vs. Defects (found after release). Technical reviews aim to find errors early to prevent them from becoming costly defects. Defect amplification model: Errors multiply as they pass through process stages. Reviews significantly reduce this. 10.2 Review Metrics and Their Use Metrics: Preparation effort ($E_p$), assessment effort ($E_a$), rework effort ($E_r$), work product size ($WPS$), minor errors ($Err_{minor}$), major errors ($Err_{major}$). Total review effort: $E_{review} = E_p + E_a + E_r$. Total errors: $Err_{tot} = Err_{minor} + Err_{major}$. Error density: $Err_{tot} / WPS$. Reviews save time and effort in the long run. 10.3 Reviews: A Formality Spectrum Formality depends on product, timeline, people. Characteristics: Roles, planning/preparation, meeting structure, correction/verification. 10.4 Informal Reviews Desk check, casual meeting, pair programming. Less formal, but still effective for early error detection. Use checklists to guide. 10.5 Formal Technical Reviews (FTR) Objectives: Uncover errors (function, logic, implementation), verify requirements, ensure standards, promote uniformity, make projects manageable. Review Meeting: 3-5 people, $\le 2$ hours prep, $\le 2$ hours meeting. Producer "walks through" product; reviewers raise issues. Decisions: Accept, reject (re-review needed), accept provisionally (minor fixes). Reporting: Review issues list, summary report (what, who, findings/conclusions). Guidelines: Review product, not producer; set/maintain agenda; limit debate; enunciate problems, don't solve; take notes; limit participants/insist on prep; use checklists; allocate resources; train reviewers; review early reviews. Sample-Driven Reviews: Inspect a fraction of work products, estimate total faults, focus resources on most error-prone. XI. Software Quality Assurance (SQA) 11.1 Background Issues "Planned and systematic pattern of actions" to ensure high quality. SQA group acts as customer's in-house representative. 11.2 Elements of Software Quality Assurance Standards: Ensure compliance. Reviews and audits: Technical reviews (error detection), audits (process compliance). Testing: Ensure proper planning and execution. Error/defect collection and analysis: Understand error introduction. Change management: Ensure adequate practices. Education: Sponsor training for process improvement. Vendor management: Ensure quality of acquired software. Security management: Ensure data protection and software integrity. Safety: Assess impact of software failure in critical systems. Risk management: Ensure proper conduct of risk activities. 11.3 SQA Tasks, Goals, and Metrics SQA Plan: Road map for SQA activities. Reviews software engineering activities: Verify process compliance. Audits work products: Verify compliance with standards. Manages deviations: Documents and tracks. Reports noncompliance: To senior management. Goals: Requirements quality, design quality, code quality, quality control effectiveness. Metrics for each goal (e.g., ambiguity, completeness, complexity, maintainability). 11.4 Formal Approaches to SQA Mathematically based techniques (e.g., correctness proofs) to demonstrate program conformance to specifications. 11.5 Statistical Software Quality Assurance (SSQA) Quantitative approach to quality. Collect and categorize error/defect info. Trace errors/defects to underlying causes. Use Pareto principle ($80/20$) to isolate "vital few" causes. Correct problems causing errors/defects. Six Sigma: Rigorous, disciplined methodology to measure and improve performance by eliminating defects. DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) for existing processes. DMADV (Define, Measure, Analyze, Design, Verify) for new processes. 11.6 Software Reliability "Probability of failure-free operation of a computer program in a specified environment for a specified time." Failure: Nonconformance to requirements. Measures: Mean-Time-Between-Failure (MTBF) = MTTF + MTTR. Failures-in-Time (FIT): Failures per billion hours. Availability = MTTF / (MTTF + MTTR) * 100%. Software Safety: SQA activity focusing on identifying/assessing potential hazards from software failure. 11.7 ISO 9000 Quality Standards Generic standard for quality management systems. ISO 9001:2000 requirements: management responsibility, quality system, contract review, design control, etc. Ensures products/services satisfy customer expectations by meeting specifications. 11.8 The SQA Plan Road map for SQA. Identifies evaluations, audits, standards, error reporting, work products, feedback, SCM procedures, records, roles/responsibilities. XII. Software Testing Strategies 12.1 Strategic Approach to Software Testing Planned, systematic set of activities to find errors. Begins at component level, works "outward." Different techniques for different stages. Conducted by developer and independent test group (ITG). Debugging is accommodated. Verification: "Are we building the product right?" (Ensures correct implementation of function). Validation: "Are we building the right product?" (Ensures traceability to customer requirements). 12.2 Organizing for Software Testing Developer tests individual units/components. ITG (Independent Test Group) removes conflict of interest, gets involved early in analysis/design. 12.3 Software Testing Steps Unit Testing: Focuses on smallest design unit (component/module). Tests: interface, local data structures, independent paths, boundary conditions, error-handling paths (antibugging). Uses drivers (main program to pass data) and stubs (replace subordinate modules). Integration Testing: Combines unit-tested components, uncovers interface errors. Nonincremental ("Big Bang"): All components combined at once; chaotic. Incremental: Top-down: Integrates modules downward from main control. Depth-first or breadth-first. Needs stubs. Bottom-up: Integrates atomic modules first, then clusters. Needs drivers. Regression Testing: Re-executes subset of tests after changes to ensure no unintended side effects. Smoke Testing: Daily integration of code into a build, tests for "showstopper" errors. Critical Modules: Address several requirements, high control, complex/error-prone, performance-critical. Test early. Work Products: Test Specification (plan, procedure, test cases, expected results, report). Validation Testing: At culmination of integration, verifies conformity with requirements. Criteria: Functional, behavioral, content, performance, documentation, usability. Configuration Review: Ensures all configuration elements properly developed and cataloged. Alpha Testing: At developer's site by representative users. Beta Testing: At end-user sites, unsupervised. Customer Acceptance Testing: Formal testing for custom software delivery. System Testing: Tests software with other system elements (hardware, people, info). Recovery Testing: Forces software failure to verify recovery. Security Testing: Verifies protection mechanisms against penetration. Stress Testing: Executes system with abnormal quantity/frequency/volume of resources. Performance Testing: Tests run-time performance within integrated system. Deployment Testing (Configuration Testing): Exercises software in each target environment. 12.4 The Art of Debugging Process of finding and correcting errors after a test uncovers them. Difficulties: Symptom/cause remote, temporary disappearance, nonerrors, human error, timing problems, difficult to reproduce, intermittent, distributed causes. Strategies: Brute Force: Memory dumps, traces, print statements. Least efficient. Backtracking: Trace code backward from symptom. Effective for small programs. Cause Elimination: Induction/deduction, binary partitioning, hypothesize causes, test to prove/disprove. Correcting Error: Ask: Reproduce elsewhere? Next bug from fix? Prevented how? XIII. Testing Object-Oriented Applications 13.1 Broadening the View of Testing Includes error discovery in OOA and OOD models via technical reviews. Same semantic constructs (classes, attributes, operations, messages) appear at analysis, design, code levels. 13.2 Testing OOA and OOD Models Cannot be executed, but reviewed for correctness, completeness, consistency. Correctness: Syntactic (proper use of symbology), semantic (conformance to real-world problem). Consistency: Examine relationships among entities in model. Use CRC model, object-relationship diagrams. 13.3 Object-Oriented Testing Strategies Unit Testing (Class Testing): Smallest testable unit is encapsulated class. Focus on operations encapsulated by class and its state behavior. Integration Testing: Thread-based testing: Integrates classes for one input/event. Use-based testing: Tests independent classes first, then dependent layers. Cluster testing: Exercises cluster of collaborating classes. Validation Testing: Focuses on user-visible actions and outputs. Uses use cases, object-behavior model, event flow diagrams. 13.4 Object-Oriented Testing Methods Each test case uniquely identified, purpose stated, steps developed (states, messages, exceptions, external conditions). Test-Case Design Implications of OO Concepts: Encapsulation can make state reporting difficult. Inheritance requires retesting of derived classes. Applicability of Conventional Methods: White-box (basis path, loop, data flow) for operations. Black-box (use cases) for validation. Fault-Based Testing: Design tests for plausible faults (unexpected result, wrong operation, incorrect invocation). Test Cases and Class Hierarchy: Test derived classes for inherited operations if behavior changes. Scenario-Based Test Design: Concentrates on user tasks (use cases) to uncover interaction errors. Testing Surface Structure and Deep Structure: Surface (externally observable, user tasks), Deep (internal technical details, dependencies). 13.5 Testing Methods Applicable at the Class Level Random Testing: Generate random operation sequences to exercise class instance life histories. Partition Testing: Reduces test cases by categorizing input/output. State-based, attribute-based, category-based partitioning. 13.6 Interclass Test-Case Design Tests collaborations between classes. Multiple Class Testing: Generate random test sequences, trace message calls through collaborating classes. Tests Derived from Behavior Models: Use state diagrams to derive test sequences covering all states and transitions. XIV. Testing Web Applications 14.1 Testing Concepts for WebApps Quality Dimensions: Content, function, structure, usability, navigability, performance, compatibility, interoperability, security. Errors: Client-side symptoms, difficult to reproduce, configuration-traced, client/server/network layers, static/dynamic environment issues. Strategy: Review models, test UI, unit test components, test navigation, compatibility, security, performance, user testing. Test Planning: Identifies tasks, work products, evaluation, recording, reuse. 14.2 The Testing Process WebApp testing juxtaposed with design pyramid. User-visible elements tested first, then infrastructure. Steps: Content, Interface, Navigation, Component, Configuration, Performance, Security. 14.3 Content Testing Uncover syntactic (typos, grammar), semantic (accuracy, completeness), and structural (organization) errors. Reviews for semantic errors (factual, concise, layout, references, consistency, legal, links). Tests for content architecture errors (e.g., wrong photo with description). Database Testing: For dynamic content from DBMS. Tests: user request translation to SQL, communication between WebApp/DBMS, raw data validity, content object formatting, client environment compatibility. 14.4 User Interface Testing Verification/validation during analysis, design, and testing. Strategy: Uncover errors in specific mechanisms, and semantics of navigation/functionality. Interface Mechanisms: Links, forms, client-side scripting, dynamic HTML, pop-up windows, CGI scripts, streaming content, cookies, application-specific mechanisms. Interface Semantics: Evaluate how design guides users, provides feedback, maintains consistency. Test use cases/NSUs. Usability Tests: Determine ease of interaction. Categories: interactivity, layout, readability, aesthetics, display, time sensitivity, personalization, accessibility. Compatibility Tests: Uncover problems due to different client/server configurations (hardware, OS, browsers, plug-ins, connectivity). 14.5 Component-Level Testing Focuses on WebApp functions (software components). Methods: Equivalence partitioning, boundary value analysis, path testing (if complex logic). Forced Error Testing: Drive component into error condition to test error handling. 14.6 Navigation Testing Ensures navigation mechanisms are functional and NSUs achievable. Navigation Syntax: Links (internal, external, anchors), redirects, bookmarks, frames/framesets, site maps, internal search engines. Navigation Semantics: Test NSUs (navigation paths linking nodes) for completeness, correctness, user understanding of location. 14.7 Configuration Testing Tests WebApp with probable client/server configurations for compatibility. Server-Side Issues: OS compatibility, file creation, security measures, distributed configuration, database integration, scripts, admin errors, proxy servers. Client-Side Issues: Hardware, OS, browser, UI components, plug-ins, connectivity. 14.8 Security Testing Probes vulnerabilities in client-side, network, server-side environments. Vulnerabilities: buffer overflow, unauthorized cookie access, spoofing, DoS, malicious scripts, unauthorized database access. Protection: Firewalls, authentication, encryption, authorization. 14.9 Performance Testing Uncovers performance problems (server resources, network, database, OS, functionality). Objectives: Server response time, performance thresholds, component bottlenecks, security impact, reliability impact, failure behavior. Load Testing: Simulates real-world loading (users, transactions, data volume). Stress Testing: Forces loading beyond operational limits to determine failure points, degradation behavior. XV. Formal Modeling and Verification 15.1 The Cleanroom Strategy Emphasizes correctness verification before testing. Incremental software model. Tasks: Increment planning, requirements gathering, box structure specification, formal design, correctness verification, code generation/inspection/verification, statistical test planning, statistical use testing, certification. 15.2 Functional Specification (Box Structure Specification) Refinement process with referential transparency. Black Box: Specifies system behavior (stimuli, responses, transition rules). State Box: Encapsulates state data and services, represents stimulus history. Clear Box: Defines transition functions implied by state box (procedural design). 15.3 Cleanroom Design Rigorously applies structured programming (sequences, conditionals, loops). Data encapsulation, information hiding, data typing for data design. Design Refinement: Stepwise expansion of functions, formal correctness verification at each level. Design Verification: Proof of correctness for procedural design. 15.4 Cleanroom Testing Validates software requirements by demonstrating successful execution of statistical sample of use cases. Statistical Use Testing: Determines usage probability distribution for stimuli, generates random test cases according to distribution. Certification: Reliability (MTTF) specified for each component. Models: sampling, component, certification. 15.5 Formal Methods Concepts Mathematically based techniques for describing system properties. Aims for consistency, completeness, lack of ambiguity. Data Invariant: Condition true throughout system execution. State: System's stored data (Z language) or observable behavior mode. Operation: Action that reads/writes data. Associated with invariants, preconditions, postconditions. 15.6 Applying Mathematical Notation for Formal Specification Uses set theory and logic notation. Example: block handler (used, free blocks, block queue). Rigorously defines data invariants, preconditions, postconditions. 15.7 Formal Specification Languages Syntax, semantics, relations. Object Constraint Language (OCL): Formal notation for UML, ASCII-based. Expressions are constraints, result in Boolean. Context, property, operation, keywords. Z Specification Language: Uses typed sets, relations, functions within first-order predicate logic to build schemas. Schema: declares variables, specifies relationships, defines state, operations. XVI. Software Configuration Management (SCM) 16.1 SCM Overview Manages change throughout software life cycle. Activities: identify, control, ensure proper implementation, report changes. Not software support. Initiated at project start, ends when software retired. 16.2 SCM Scenario Roles: project manager (auditing), configuration manager (controlling, tracking), software engineers (changing, building), customer (quality assurance). 16.3 Elements of a Configuration Management System Component elements: Tools + file management for SCIs. Process elements: Actions/tasks for change management. Construction elements: Tools to automate software construction from validated components. Human elements: Tools/process features used by team. 16.4 Baselines Specification/product formally reviewed and agreed upon, basis for further development, changed only through formal control. Milestone in development. SCIs approved and placed in project database. 16.5 Software Configuration Items (SCIs) Named element of information (UML diagram, test case, program component). Can include software tools. Organized into configuration objects (name, attributes, relationships). 16.6 The SCM Repository Database for accumulation and storage of software engineering information. Features: versioning, dependency tracking/change management, requirements tracing, configuration management, audit trails. 16.7 The SCM Process Objectives: identify configuration items, manage change, facilitate version construction, ensure quality. Tasks: identification, version control, change control, configuration auditing, reporting. 16.8 Identification of Objects in the Software Configuration Basic objects (unit of information) and aggregate objects (collection of basic/aggregate objects). Each object: name, description, resources, realization. 16.9 Version Control Procedures/tools to manage different versions of configuration objects. Capabilities: project database, version management, make facility, issues tracking. Change set: collection of all changes for a specific version. 16.10 Change Control Human procedures and automated tools for managing change. Change request $\rightarrow$ evaluation $\rightarrow$ change report $\rightarrow$ Change Control Authority (CCA) decision $\rightarrow$ Engineering Change Order (ECO). Access control and synchronization control. Layered control: informal (pre-baseline), project-level (baselined), formal (released to customers). 16.11 Configuration Audit Complements technical review. Ensures change implemented properly. Questions: Change made? Review conducted? Process followed? SCM procedures followed? Related SCIs updated? 16.12 Status Reporting Answers: What happened? Who did it? When? What else affected? 16.13 Configuration Management for WebApps WebApp change: continuous evolution, immediacy. Issues: Content (organize into objects, properties), people (non-technical creators), scalability (techniques must scale), politics (who "owns" WebApp). WebApp Configuration Objects: Content, functional components, interface objects. Content Management (CMS): Acquires, structures, and presents content. Subsystems: collection (create/acquire content), management (store, catalog, label), publishing (extract, convert, format for client). Change Management: Categorize changes (Class 1-4) and process accordingly (informal to formal). Version Control: Central repository, working folders, synchronized clocks, automatic logging. Auditing and Reporting: De-emphasized for agility, but logs and notifications maintained. XVII. Product Metrics 17.1 Framework for Product Metrics Measure: Quantitative indication of extent, amount, dimension, capacity, size. Measurement: Act of determining a measure. Metric: Quantitative measure of degree to which system/component possesses attribute. Indicator: Metric/combination providing insight for adjustment. Measurement Principles: Formulation, collection, analysis, interpretation, feedback. Goal-Oriented Software Measurement (GQM): Define goal, questions, metrics. Attributes of Effective Software Metrics: Simple, computable, empirically/intuitively persuasive, consistent, objective, consistent units, programming language independent, effective feedback. 17.2 Metrics for the Requirements Model Function-Based Metrics (Function Points - FP): Measure functionality delivered. Counts: External inputs (EI), external outputs (EO), external inquiries (EQ), internal logical files (ILF), external interface files (EIF). Adjusted by Value Adjustment Factors (VAFs) for problem complexity. Metrics for Specification Quality: Specificity (lack of ambiguity): $Q_1 = N_{ui} / N_r$ (unique interpretations / total requirements). Completeness (functional): $Q_2 = N_u / (N_i + N_s)$ (unique functions / (inputs + states)). Completeness (validated): $Q_3 = N_c / (N_c + N_{nv})$ (correct / (correct + not validated)). 17.3 Metrics for the Design Model Architectural Design Metrics: Focus on program architecture. Structural complexity ($S(i)$), data complexity ($D(i)$), system complexity ($C(i)$). Morphology metrics: Size, depth, width, arc-to-node ratio. Design Structure Quality Index (DSQI): Based on module characteristics. Metrics for Object-Oriented Design: Characteristics: Size, complexity, coupling, sufficiency, completeness, cohesion, primitiveness, similarity, volatility. CK Metrics Suite: Weighted methods per class (WMC): Sum of method complexities. Depth of the inheritance tree (DIT): Max length from node to root. Number of children (NOC): Subclasses immediately subordinate. Coupling between object classes (CBO): Number of collaborations. Response for a class (RFC): Number of methods executable in response to message. Lack of cohesion in methods (LCOM): Methods accessing common attributes. MOOD Metrics Suite: Method inheritance factor (MIF), coupling factor (CF). Lorenz and Kidd: Class size (CS), inheritance, internals, externals. Component-Level Design Metrics (Conventional): Cohesion metrics (data slice, tokens). Coupling metrics (data/control flow, global, environmental). Complexity metrics (cyclomatic complexity). Operation-Oriented Metrics: Average operation size (OSavg), operation complexity (OC), average number of parameters per operation (NPavg). User Interface Design Metrics: Layout appropriateness, layout complexity, recognition complexity/time, typing/mouse effort, selection complexity, content acquisition time, memory load. 17.4 Design Metrics for WebApps Interface metrics, aesthetic (graphic design) metrics, content metrics, navigation metrics. 17.5 Metrics for Source Code Halstead's Software Science: Primitive measures (distinct operators/operands, total occurrences) to derive program length, volume, level, effort, time, faults. 17.6 Metrics for Testing Halstead metrics applied to testing: Percentage of testing effort for a module. Metrics for Object-Oriented Testing: LCOM, PAP, PAD, NOR, FIN, NOC, DIT (all influence testability). 17.7 Metrics for Maintenance Software Maturity Index (SMI): Indication of product stability. $SMI = (M_T - (F_c + F_a + F_d)) / M_T$ $M_T$: modules in current release. $F_c$: changed modules. $F_a$: added modules. $F_d$: deleted modules from preceding release. XVIII. Managing Software Projects 18.1 The Management Spectrum Focuses on 4 P's: People, Product, Process, Project. 18.2 People Stakeholders: Senior managers, project managers, practitioners, customers, end users. Team Leaders (MOI Model): Motivation, Organization, Ideas/Innovation. Traits: problem-solving, managerial identity, achievement, influence/team building. Software Team: Structure depends on problem difficulty, size, lifetime, modularity, quality, delivery date, sociability. Organizational paradigms: closed, random, open, synchronous. "Jelled team": strongly knit, greater than sum of parts. "Team toxicity": frenzied work, high frustration, fragmented process, unclear roles, repeated failure. Agile Teams: Self-organizing, autonomous, emphasize competency and collaboration. Coordination & Communication: Formal (writing, structured meetings) and informal (ad hoc interactions). 18.3 Product Software Scope: Context, information objectives, function and performance. Must be bounded. Feasibility: Technical, financial, time, resources. Problem Decomposition: Partition functionality/content and process to make manageable. 18.4 Process Select appropriate process model (linear, iterative, evolutionary). Meld product and process (matrix of functions vs. framework activities). Process Decomposition: Refine framework activities into specific work tasks. 18.5 Project Signs of Jeopardy: Lack of customer understanding, poor scope, poorly managed changes, changing technology, changing/ill-defined needs, unrealistic deadlines, user resistance, lost sponsorship, lack of skills, avoiding best practices. Commonsense Approach: Start right, maintain momentum, track progress, make smart decisions, postmortem analysis. W5HH Principle (Boehm): Why, What, When, Who, Where, How, How much. Critical Practices (Airlie Council): Metric-based management, empirical estimation, earned value tracking, defect tracking, people-aware management. XIX. Estimation for Software Projects 19.1 Observations on Estimation Requires experience, historical data, courage. Affected by complexity, size, structural uncertainty, historical information availability. Estimates carry inherent risk. 19.2 The Project Planning Process Framework for reasonable estimates of resources, cost, schedule. Define best-case and worst-case scenarios. 19.3 Software Scope and Feasibility Scope: Functions, features, data, content, performance, constraints, interfaces, reliability. Feasibility: Technical, financial, time, resources. 19.4 Resources Human Resources: Skills, organizational position, location. Reusable Software Resources: Off-the-shelf, full-experience, partial-experience, new components. Environmental Resources: Hardware, software tools (SEE). 19.5 Software Project Estimation Options: Delay, based on similar projects, decomposition, empirical models. 19.6 Decomposition Techniques Software Sizing: "Fuzzy logic": Qualitative scale for magnitude. Function point (FP) sizing: Estimate information domain characteristics. Standard component sizing: Estimate occurrences of standard components. Change sizing: Estimate modifications to existing software. Problem-Based Estimation: LOC or FP estimated for each function/information domain value. Baseline productivity metrics (LOC/pm or FP/pm) applied. Three-point/expected value: $S = (S_{opt} + 4S_m + S_{pess}) / 6$. Process-Based Estimation: Decompose process into tasks, estimate effort for each. Apply average labor rates. Estimation with Use Cases: Problematic due to varying formats, abstraction levels, complexity. 19.7 Empirical Estimation Models Predict effort as function of LOC or FP using regression analysis. Structure: $E = A \times B \times (ev)^C$. COCOMO II: Hierarchy of models (application composition, early design, post-architecture). Object points: Counts of screens, reports, components. The Software Equation: Dynamic multivariable model from productivity data. $E = (LOC / (P \times t^{4/3}))^3 / B$ $t_{min} = 8.14 \times (LOC / P)^{0.43}$ (minimum development time). 19.8 Estimation for Object-Oriented Projects Metrics: Number of scenario scripts, key classes, support classes, support classes per key class, subsystems. 19.9 Specialized Estimation Techniques Agile Development: Decompose scenarios into tasks, estimate effort/volume, sum for increment. WebApp Projects: Modified function points (inputs, outputs, tables, interfaces, queries). 19.10 The Make/Buy Decision Acquisition options: off-the-shelf, reusable components, custom-built by contractor. Decision based on: delivery date, cost (acquisition + customization vs. internal development), support cost. Decision Tree Analysis: Calculates expected cost for different options. Outsourcing: Strategic or tactical. Cost savings vs. loss of control. XX. Project Scheduling 20.1 Basic Concepts Root causes of late delivery: Unrealistic deadlines, changing requirements, underestimates, unconsidered risks, technical/human difficulties, miscommunication, management inaction. Scheduling distributes estimated effort across planned duration. 20.2 Basic Principles Compartmentalization, interdependency, time allocation, effort validation, defined responsibilities, defined outcomes, defined milestones. 20.3 The Relationship Between People and Effort Adding people late makes project later (Brooks' Law). PNR Curve: Relationship between effort and delivery time. Minimum cost at optimal delivery time. Software Equation shows nonlinear relationship. 20.4 Effort Distribution 40-20-40 rule: 40% analysis/design, 20% coding, 40% testing. Guidelines only; characteristics of project dictate distribution. 20.5 Defining a Task Set Collection of work tasks, milestones, work products, quality filters. Project types: concept development, new application, enhancement, maintenance, reengineering. Refinement of Software Engineering Actions: Decompose actions into tasks/subtasks. 20.6 Defining a Task Network Graphic representation of task flow. Depicts major actions, interdependencies, critical path. 20.7 Scheduling PERT (Program Evaluation and Review Technique) and CPM (Critical Path Method). Time-Line Charts (Gantt Chart): Visualizes task duration, concurrency, milestones. Tracking the Schedule: Status meetings, reviews, milestone checks, informal talks, earned value analysis. Time-Boxing: For severe deadline pressure. Fixed schedule for increments; tasks adjusted to fit. Tracking Progress for an OO Project: Milestones for analysis, design, programming, testing completion. Scheduling for WebApp Projects: Macroscopic schedule for increments, then refined detailed schedule for tasks within increments. 20.8 Earned Value Analysis (EVA) Quantitative analysis of progress. Budgeted Cost of Work Scheduled (BCWS): Planned effort for tasks. Budget at Completion (BAC): Total BCWS for all tasks. Budgeted Cost of Work Performed (BCWP): BCWS for completed tasks. Schedule Performance Index (SPI): BCWP / BCWS (efficiency of schedule use). Schedule Variance (SV): BCWP - BCWS. Percent Scheduled for Completion: BCWS / BAC. Percent Complete: BCWP / BAC. Actual Cost of Work Performed (ACWP): Effort expended on completed tasks. Cost Performance Index (CPI): BCWP / ACWP. Cost Variance (CV): BCWP - ACWP. XXI. Risk Management 21.1 Reactive Versus Proactive Risk Strategies Reactive: Monitors for risks, acts only when problems occur ("fire-fighting"). Proactive: Identifies, assesses, ranks risks, plans mitigation/contingency. 21.2 Software Risks Always involve uncertainty and loss. Project Risks: Threaten project plan (schedule, cost, staffing, resources, stakeholders, requirements). Technical Risks: Threaten quality/timeliness (design, implementation, interface, verification, maintenance, ambiguity, obsolescence). Business Risks: Threaten viability of software (market, strategic, sales, management, budget risks). Known, Predictable, Unpredictable Risks. 21.3 Risk Identification Systematic attempt to specify threats. Generic Risks: Threat to every project. Product-Specific Risks: Unique to the software being built. Risk Item Checklist: Categories like size, business impact, stakeholder characteristics, process, environment, technology, staff. Assessing Overall Project Risk: Questions about commitment, understanding, expectations, scope stability, team skills, requirements stability, technology experience, staff adequacy, stakeholder agreement. Risk Components and Drivers (U.S. Air Force): Performance, cost, support, schedule. Impact categories: negligible, marginal, critical, catastrophic. 21.4 Risk Projection (Estimation) Rate each risk by likelihood (probability) and consequences (impact). Risk Table: Lists risks, category, probability, impact (1-4 scale), RMMM pointer. Sorts by probability and impact for prioritization. Overall Risk Exposure (RE) = P $\times$ C (probability $\times$ cost). 21.5 Risk Refinement Refine general risks into detailed sub-risks. Condition-Transition-Consequence (CTC) format: Given , then concern that . 21.6 Risk Mitigation, Monitoring, and Management (RMMM) Mitigation (avoidance): Develop plan to reduce likelihood/impact (e.g., for high staff turnover: meet staff, mitigate causes, ensure continuity, disperse knowledge, use work product standards, peer reviews, backup staff). Monitoring: Track factors indicating risk likelihood, effectiveness of mitigation. Management & Contingency Planning: Assumes mitigation failed, risk is reality. Refocus resources, knowledge transfer. RMMM steps incur costs; perform cost-benefit analysis. Pareto 80-20 rule for critical risks. Software safety and hazard analysis. RMMM Plan: Documents risk analysis, mitigation, monitoring, management. Risk Information Sheet (RIS) for individual risks. XXII. Maintenance and Reengineering 22.1 Software Maintenance Correcting bugs, adapting to new environments, enhancing functionality. Often 60-70% of resources. Due to old code, new platforms, enhancements without architectural regard, staff turnover. Maintainability: Qualitative indication of ease of correction, adaptation, enhancement. 22.2 Software Supportability Capability of supporting software system over its whole product life. Includes ongoing operational/end-user support, reengineering. Software should contain antibugging facilities, support personnel need defect database. 22.3 Reengineering "Obliterate outdated processes and start over." (Hammer). Modify or rebuild existing applications. 22.4 Business Process Reengineering (BPR) "Search for, and implementation of, radical change in business process to achieve breakthrough results." Business Process: Set of logically related tasks to achieve outcome. Customer-focused, cross-organizational. BPR Model (Iterative): Business definition (goals). Process identification (critical processes). Process evaluation (analyze, measure existing process). Process specification and design (use cases for redesigned process). Prototyping (test new process). Refinement and instantiation. 22.5 Software Reengineering Addresses unmaintainable software. Process Model: Inventory analysis $\rightarrow$ document restructuring $\rightarrow$ reverse engineering $\rightarrow$ data restructuring $\rightarrow$ code restructuring $\rightarrow$ forward engineering. Inventory Analysis: Spreadsheet of applications (size, age, criticality, maintainability) to identify reengineering candidates. Document Restructuring: Update/create documentation (live with what you have, "document when touched," fully redocument). Reverse Engineering: Analyze program to create higher-level abstraction. Design recovery. Abstraction level (procedural, program/data structure, object, data/control flow, ER models). Completeness, interactivity, directionality. Data: Program-level (group related variables), system-level (global data structures). Processing: Understand/extract procedural abstractions (system, program, component). User Interfaces: Understand structure/behavior (basic actions, behavioral response, equivalence). Restructuring: Modify source code/data to make amenable to future changes. Does not modify overall architecture. Code Restructuring: Yields same function, higher quality. Uses restructuring tools, conforms to structured programming. Data Restructuring: Reengineers data architecture (data record standardization, name rationalization, physical modifications). Forward Engineering: Re-create existing application, integrating new requirements. Client-Server Architectures: Migrate mainframe to client-server. Requires business/software reengineering, network infrastructure. Object-Oriented Architectures: Reengineer conventional software to integrate into OO systems. Uses reverse engineering for models, then OO design. Economics of Reengineering: Cost-benefit analysis. $C_{maint} = [P_3 - (P_1 + P_2)] \times L$ $C_{reeng} = P_6 + (P_4 + P_5) \times (L / P_8) \times P_7 \times P_9$ $Cost_{benefit} = C_{reeng} - C_{maint}$ XXIII. Software Process Improvement (SPI) 23.1 What is SPI? Defines effective process elements, assesses existing approach, defines improvement strategy. Delivers ROI: reduces defects, rework, maintenance costs, late delivery. 23.2 Approaches to SPI SPI Frameworks: Define characteristics, assessment methods, summary mechanisms, improvement strategies. Constituencies: Quality certifiers, formalists, tool advocates, practitioners, reformers, ideologists. 23.3 Maturity Models Overall indication of "process maturity." Ordinal scale. CMM (Software Engineering Institute): Level 1: Initial (ad hoc, heroic efforts). Level 2: Repeatable (basic project management). Level 3: Defined (documented, standardized processes). Level 4: Managed (quantitative evaluation, predictable quality). Level 5: Optimized (continuous improvement, proactive defect prevention). Schorsch's Immaturity Levels: Negligent, obstructive, contemptuous, undermining. 23.4 Is SPI for Everyone? Yes, but adapted for small organizations. Must demonstrate financial leverage (ROI). 23.5 The SPI Process (IDEAL Model) Assessment and Gap Analysis: Uncover strengths/weaknesses. Examine consistency, sophistication, acceptance, commitment. Education and Training: Generic concepts, specific technology, business/quality topics. Selection and Justification: Choose process model, methods, tools. Installation/Migration: Implement changes (new process, process migration). Process redesign (SPR). Evaluation: Assess adopted changes, quality benefits, process status. Risk Management for SPI: Analyze risks (lack of management support, cultural resistance, poor planning, etc.). Critical Success Factors (CSFs): Management commitment, staff involvement, process integration, customized strategy, solid management of SPI project. 23.6 The CMMI Comprehensive process meta-model. Continuous and staged models. Capability Levels (0-5): Incomplete, Performed, Managed, Defined, Quantitatively Managed, Optimized. Defines process areas (e.g., Project Planning) with specific goals (SG) and specific practices (SP). Generic goals (GG) and practices (GP) for each capability level. 23.7 The People CMM Roadmap for improving workforce capability. Organizational maturity levels (Initial, Managed, Defined, Quantitatively Managed, Optimizing) tied to Key Process Areas (KPAs). 23.8 Other SPI Frameworks SPICE: International initiative for ISO process assessment. Bootstrap: SPI for small/medium organizations, SPICE compliant. PSP and TSP: Individual and team-specific SPI frameworks. TickIT: Auditing method for ISO 9001:2000 compliance. 23.9 SPI Return on Investment $ROI = (\sum benefits - \sum costs) / \sum costs \times 100\%$. Benefits: cost savings, reduced rework, faster time-to-market. Costs: direct SPI, indirect (quality control, methods). 23.10 SPI Trends More agile, project-level focus. Simpler models. Web-based training. Cultural change one group at a time. XXIV. Emerging Trends in Software Engineering 24.1 Technology Evolution Technological evolution is exponential. Innovation Life Cycle: Breakthrough $\rightarrow$ Replicator $\rightarrow$ Empiricism $\rightarrow$ Theory $\rightarrow$ Automation $\rightarrow$ Maturity. Computing technologies at the "knee" of S-curve, leading to explosive growth. 24.2 Observing Software Engineering Trends Challenges: rapid change, uncertainty, emergence, dependability, diversity, interdependence. Gartner Group Hype Cycle: Technology trigger $\rightarrow$ Peak of inflated expectations $\rightarrow$ Trough of disillusionment $\rightarrow$ Slope of enlightenment $\rightarrow$ Plateau of productivity. 24.3 Identifying "Soft Trends" Connectivity and Collaboration: Distributed teams across time zones, language, culture. Globalization: Diverse workforce, flexible organizational structure. Aging Population: Knowledge capture for future generations. New Consumers/Demand: Increased demand for software. Human Culture: Shapes technology direction. 24.4 Managing Complexity Software systems growing in LOC (millions, billions). Challenges: interfaces, project management, coordination, requirements analysis, design architecture, change management, quality assurance. 24.5 Open-World Software Ambient intelligence, context-aware applications, pervasive/ubiquitous computing. Adapts to continually changing environment by self-organizing structure and self-adapting behavior. Example: P-com (personal communicator) and trust management system. 24.6 Emergent Requirements Requirements emerge as understanding grows. Implies agile process models, judicious use of models, tools supporting adaptation. Open-world software demands dynamic adaptation to unanticipated changes. 24.7 The Talent Mix Diverse creative talent and technical skills for complex systems. Example "dream team" roles: Brain (chief architect), Data Grrl (database guru), Blocker (technical manager), Hacker (programmer), Gatherer (requirements). 24.8 Software Building Blocks Reuse of source code, OO classes, components, patterns, COTS. "Merchant software" and software platform solutions. 24.9 Changing Perceptions of "Value" From business value (cost, profitability) to customer values (speed, richness, quality). 24.10 Open Source Development method harnessing distributed peer review and process transparency. Promises better quality, reliability, flexibility, lower cost, end to vendor lock-in. 24.11 Technology Directions Process Trends: Goal-oriented, product innovation focus; bottom-up, simple scorecards; automated SPT for umbrella activities; ROI emphasis; expertise in sociology/anthropology; new modes of learning. The Grand Challenge: Engineering large, complex systems (multifunctionality, reactivity/timeliness, new UI modes, complex architectures, heterogeneous/distributed systems, criticality, maintenance variability). Collaborative Development: Information sharing across global teams. Shared goals, culture, process, responsibility. Requirements Engineering: Improved knowledge acquisition/sharing, iteration, effective communication/coordination tools. Model-Driven Software Development (MDSD): Domain-specific modeling languages (DSMLs) with transformation engines. Postmodern Design: Emphasizes architecture, decisions, assumptions, constraints, implications. Test-Driven Development (TDD): Requirements $\rightarrow$ test cases $\rightarrow$ code to satisfy test. Iterative, regression testing. Tools-Related Trends: Human-focused (collaborative SEEs) and technology-centered (MDSD, architecture-driven design).